Sleep and Gastroesophageal Reflux

Introduction

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is common in children of all ages and can impact sleep. In infants, it is the most common GI problem presenting to the pediatrician’s office.1 Despite its high prevalence, minimal research is available examining the impact of GERD on sleep in children.

Gastroesophageal reflux (GER) is the retrograde passage of gastric contents into the esophagus and it is normally seen post-prandially. Regurgitation is a symptom of GER and is common in infants.2 The refluxate is acidic and contains digestive enzymes that can injure the mucosal lining of the esophagus and upper airway. Intrinsic protective mechanisms exist to prevent or minimize this damage. Reflux becomes pathologic GERD when GER episodes are more frequent and produce symptoms including heartburn, esophagitis, failure to thrive, or respiratory symptoms such as cough and wheeze.2

Esophageal Physiology

The esophagus develops initially during the fourth week of gestation as a small outgrowth of the endoderm and later includes all three germ layers: the endoderm, mesoderm, and ectoderm. These layers give rise, respectively, to the epithelial lining; muscular layers, angioblast, and mesenchyme; and the neural components.3

The esophagus slowly increases its length so that at 20 weeks of gestation, esophageal length approximates 11 cm.4 Esophageal length doubles during the first year of life.3 Ultimately, the esophageal body in adults has a length of 18–22 cm, with the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) representing the distal 2–4 cm of the esophagus.5 The LES grows from a few millimeters in newborns and reaches its adult length during adolescence. In older children, the proximal 1.5–2 cm of the LES is encircled by the crural diaphragm and sits in the thoracic cavity, and the lower 2 cm resides in the abdominal cavity.5

The esophagus consists of three functionally distinct zones, including the upper esophageal sphincter (UES), the esophageal body, and the lower esophageal sphincter (LES).3

The UES is an intraluminal high-pressure zone located between the pharynx and the cervical esophagus. The anterior wall includes the posterior surface of the cricoid cartilage, the arytenoid cartilage, and the interarytenoid muscles. The posterior wall includes the cricopharyngeus and thyropharyngeus muscles. The UES prevents refluxate from getting into the upper airway, and it prevents air from entering the esophagus during inspiration. The UES opens during belching, rumination, deglutition, regurgitation, and vomiting.3

The esophageal body begins at the edge of the cricopharyngeal muscle and, in adults, is comprised of striated skeletal muscle for the first 4–5 cm, followed by a transitional zone that contains both skeletal muscle and smooth muscle cells. The distal 10–14 cm comprises smooth muscle cells.3

The LES is a high-pressure zone controlling the flow of materials between the esophagus and the stomach. The LES comprises an intrinsic muscular layer (intrinsic LES) and the extrinsic LES, which is the crural diaphragm.5 These two components of the LES are superimposed and linked together by the phrenoesophageal ligament. Both the intrinsic and extrinsic components of the LES contribute to LES competence. The LES is tonically contracted at rest and relaxes with esophageal distention and deglutination. The crural diaphragm portion of the LES creates spike-like increases in LES pressure during inspiration and relaxes with esophageal distention and vomiting.5

The esophagus accomplishes its role as a conduit to move food from the mouth to the stomach through peristalsis. The esophagus exhibits three different forms of peristalsis: primary peristalsis, secondary peristalsis, and deglutitive inhibition.6

Primary peristalsis is a reflex esophageal contraction that is initiated by swallowing and a contraction wave that moves from the pharynx to the stomach. This propulsive force is caused by the sequential contraction of the esophageal muscle layers. In children, the typical amplitude of the contraction ranges between 40 and 89 mmHg, has a duration of 2.5–5 seconds, and a propagation velocity of 3.0 cm/second.7,8

Secondary peristalsis occurs with esophageal luminal distention and is not associated with a swallow. It helps remove refluxate that was not cleared with primary peristalsis.6

Deglutitive inhibition results when a second swallow is initiated while a prior peristalsis is still occurring. This results in complete inhibition of the peristaltic contraction caused by the first swallow. With successive swallows, the esophagus remains in stasis until a final swallow produces a large ‘clearing wave’ that sweeps the esophagus of its contents.6

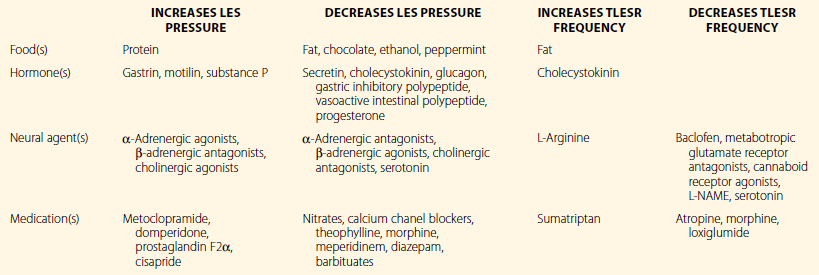

The LES is constantly adapting to the changing pressure gradients between the stomach and the esophagus in order to maintain competency. During inspiration, the pressure gradient between the stomach and esophagus is 4–6 mmHg and is countered by an LES pressure between 10 and 35 mmHg. During the migrating motor complex of esophageal contractions, the LES vigorously contracts to prevent reflux of stomach contents into the esophagus. During inspiration, there is an increasingly negative intra-esophageal pressure, while abdominal muscle contractions augment gastric pressure. Both of these situations increase the pressure gradient, predisposing to GER events. However, the contraction of the crural diaphragm during abdominal muscle contraction, vomiting, or straining helps to prevent reflux.5 In addition to abdominal and intrathoracic pressures, the LES pressure is influenced by many other factors, as listed in Table 11.1.9

Table 11.1

Factors that Influence Lower Esophageal (LES) Pressure and Transient Lower Esophageal Sphincter Relaxation (TLESR) Frequency.9

L-NAME, N(G)-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester.

Reprinted with permission from Wiley-Blackwell, publisher: From Kahrilas P, Pandolfino J. Esophageal Motor Function. In: Yamada, T, editor. Textbook of Gastroenterology. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell; 2009. p. 187–206.9

During swallowing, the LES relaxes within 1–2 seconds of the primary peristaltic contraction and this relaxation lasts approximately 5–10 seconds. When the bolus arrives at the LES, the LES pressure declines to gastric pressure, and the sphincter remains closed. Then, the intrabolus pressure forces the LES to open and the bolus enters the stomach. After 5–7 seconds, the LES rebounds to its original pressure and the LES undergoes an after-contraction, which ends the peristaltic contraction wave.6

Gas is vented from the stomach by belching, where there is a transient relaxation of the LES (TLESR). TLESRs are abrupt declines in the LES pressure to gastric pressure that are not related to primary peristalsis, secondary peristalsis, or swallowing. There is also inhibition of the crural diaphragm with TLESRs.10 TLESRs have a typical duration of 10–45 seconds. TLESRs occur up to six times per hour in normal adults and are more frequent immediately post-prandially. They occur during arousals but not during stable sleep.11

TLESRs can be triggered by gastric distention or vagal stimulation that occurs with endotracheal intubation. Gamma-amino-butyric acid (GABA) serves as an inhibitor of TLESRs.5 Table 11.1 also reviews factors influencing TLESRs.9

LES pressures in children range between 10 and 40 mmHg. LES pressures that are 5 mmHg above the intragastric pressure are usually sufficient to prevent GER.5,12 LES motor patterns in infants and children are similar to those observed in adults.5

Mechanisms of Gastroesophageal Reflux

Gastroesophageal reflux occurs when intra-abdominal pressure exceeds intrathoracic pressure and the LES barrier. GER is prevented by normal LES function. The intra-abdominal portion of the esophagus is squeezed closed by abdominal pressure. In addition, the acuity of the angle where the esophagus enters the stomach (angle of His) serves as a component of the barrier at the gastroesophageal junction. A compromise in this region, as seen in hiatal hernia, predisposes to GER.5

The majority (81% to 100%) of GER episodes in infants, children, and adults are caused by TLESRs.13 Omari et al. noted that 82% of GER episodes in premature infants and 91% of GER episodes in term infants occurred in association with TLESRs.14,15 Kawahara et al. noted TLESRs in association with 58% to 69% of GER episodes in children being evaluated for GERD.13

Protective mechanisms limit damage to the esophagus and airway. Immediately after the refluxate enters the lower esophagus, the UES contracts to prevent entry into the pharynx. Secondary peristalsis also occurs, which helps clear the refluxate. Saliva, which contains bicarbonate, is then swallowed, neutralizing any adherent acidic remnants. Finally, mucosal glands in the esophagus produce mucus and bicarbonate, limiting esophageal mucosal damage.6

Airway protective mechanisms include the UES reflex, whose function depends on refluxate volume. Small refluxate volumes result in UES contraction, while large volumes stimulate a vagally mediated relaxation of the UES, allowing the refluxate to enter the pharynx. Simultaneously, this vagal response evokes a centrally meditated apnea with laryngeal closure to prevent aspiration. In older children, apnea is not provoked, but a coughing spell occurs in this situation.16

Esophageal Physiology during Sleep

Sleep and the circadian rhythm alter upper gastroesophageal function. Gastric acid secretion peaks between 8 p.m. and 1 a.m.11 Gastric myoelectric function is disrupted by sleep, resulting in delayed gastric emptying.11 There is also delayed esophageal acid clearance during sleep. These factors predispose to GER during sleep.

The UES pressure decreases with sleep onset. Kahrilas et al. reported that UES pressure decreases from 40 ± 17 mmHg during wakefulness to 20 ± 17 mmHg during N1 sleep, and was lowest (8 ± 3 mmHg) during N3 sleep.17 The UES contractile reflex is also altered during sleep. The UES contractile reflex is triggered by smaller volumes of refluxate during REM sleep, and does not occur during N3 sleep.18 The UES reflex is preempted by coughing and/or arousal. Basal LES pressure does not change during sleep. The frequency of TLESRs declines during sleep time. Almost all TLESRs occur during wakefulness or during brief arousals from sleep.18

In addition, swallowing frequency decreases by 50% to 80% during sleep time compared to wakefulness.11 Similar to TLESRs, swallowing occurs during arousals and is almost nonexistent during stable sleep.19 Salivary secretion is not detectable during stable sleep.11 Esophageal acid clearance is also delayed during sleep. Orr et al. observed that 15 mL of 0.1 N HCl was cleared from the distal esophagus within 25 minutes during sleep, whereas it took only 6 minutes to clear when awake.19 Sleep prolongs the latency to the first swallow if esophageal acid is present. Finally, during sleep, 40% of the refluxate reaches the proximal esophagus near the UES compared to <1% during wakefulness.20 This, in addition to the lower UES pressure during sleep, might predispose to microaspiration of refluxate into the pharynx.

Despite the lack of some GERD-protective mechanisms during sleep, individual GER events are much less frequent during sleep than during wake. However, if GER occurs, the events are of a longer duration, and are more likely to result in esophagitis and Barrett’s esophagus.11

Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD)

Gastroesophageal reflux disease is a common pediatric illness and has protean manifestations.21 GERD can present with recurrent vomiting (regurgitation), poor weight gain, heartburn, chest pain, esophagitis, vomiting, Sandifer syndrome, hematemesis, anemia, Barrett’s esophagus, esophageal adenocarcinoma, asthma exacerbation, chronic cough, acute life-threatening events (ALTEs), recurrent pneumonia, sleep apnea, and dental erosions.2,22 A prospective Italian study documents that 12% of infants had regurgitation and 1% of children met criteria for GERD.23 Among US adolescents, aged 10 to 17 years, 5.2% reported heartburn and 8.2% reported acid regurgitation during the previous week.24 GERD is also more frequent during early childhood when large fluid boluses are used for feeding.2

Adolescents and older children experience similar clinical presentations as adults with GERD. Typical complaints include heartburn, dyspepsia, and regurgitation. Gupta et al. described the presenting symptoms of GERD in pediatric patients.22 The most common symptoms included abdominal pain (70%), regurgitation (69%), and cough (69%). In patients between 1 and 36 months of age, symptoms of GERD included regurgitation (98%), irritability (41%), feeding problems (10%), failure to thrive (7%) and respiratory problems (18.6%).22 Toddlers and younger children (less than 6 years) more likely reported cough, anorexia/food refusal, and vomiting.22 In a Finnish study examining children with GERD (mean age 6.7 years), the presenting symptoms included abdominal pain (63%), heartburn (34%), regurgitation (22%), vomiting (16%), retrosternal pain (18%), and respiratory symptoms (29%).25 Adolescents with GERD reported esophageal symptoms (22.4%), regurgitation (21.4%), dysphagia (14.5%), shortness of breath (24.4%), wheezing (1.7%), and cough (17.9%).26

Extra-esophageal manifestations of GERD are also present in children.27 El-Serag et al. compared 1980 children with GERD (mean age 9.2 years) to a control group without GERD, examining the association of GERD with upper and lower respiratory disorders.27 They demonstrated that children with GERD were more likely to have sinusitis (4.2% vs. 1.4%), laryngitis (0.7% vs. 0.2%), asthma (13.2% vs. 6.8%), pneumonia (6.3% vs. 2.3%), and bronchiectasis (1.0% vs. 0.1%). After adjusting for age, gender, and ethnicity, GERD remained associated with all of these conditions.27

Sleep-Related GERD

Sleep-related GERD

Sleep-related GERD may present with nocturnal awakenings with a sour taste in the mouth, burning discomfort in the chest, or nocturnal arousals. These arousals may disrupt sleep, leading to daytime sleepiness or insomnia.11

Few studies examine the epidemiology, severity, or range of clinical impact that is associated with sleep-related GERD in children. In children, GERD during sleep is associated with increased sleep arousals, sleep fragmentation, and other sleep disturbances.21 Kahn et al. evaluated 50 infants with occasional regurgitation and noted that 41 of the 50 infants had proximal GER events, with 97 episodes occurring during sleep time. Reflux during sleep time occurred commonly during wakefulness (41%), or was associated with arousals.28 This study did not determine whether arousals led to the reflux or if the reflux led to the arousal from sleep.28 Ghaem et al. examined 72 children with GERD and 3102 controls, with a questionnaire, finding that children with GERD (aged 3 to 12 months) were less likely to have ever slept through the night by 12 months of age (20%) compared to the controls.29 Fifty percent of GERD children awakened and required parental attention more than three times nightly. These findings continued in children with GERD aged 12–24 months and 24–36 months, with only 8% and 4% sleeping through the night compared to 45% and 56% of controls. Sixty percent of 12–24-month-olds and 50% of 24–36-month-olds with GERD woke up more than three times nightly. Children with GERD had more awakenings and were less likely to sleep through the night.29

A prospective randomized, controlled study in adolescents with GERD (ages 12 to 17 years) assessed the impact of 8 weeks of a proton pump inhibitor (esomeprazole) on quality of life (QOL) using the Quality of Life in Reflux and Dyspepsia Questionnaire.30 After 8 weeks of PPI, there was an improvement in the sleep dysfunction domains of the QOL instrument in the PPI-treated group. These findings suggest that GERD treatment may improve sleep in adolescents.30

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree