Skin Infections and Exanthems

Jane S. Bellet and Anthony J. Mancini

SUPERFICIAL BACTERIAL INFECTIONS

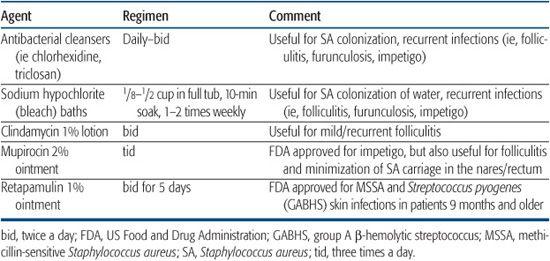

Topical therapies for some common pediatric bacterial skin infections are outlined in Table 367-1.

IMPETIGO

IMPETIGO

Impetigo is a highly contagious infection of the superficial epidermis noted predominantly in preschool-age children. Although group A β-hemolytic streptococci (GABHS) were traditionally most frequently isolated in the United States, Staphylococcus aureus now appears to predominate. Community-acquired methicillin-resistant S aureus (MRSA) has been present for more than a decade, but has more recently become more widespread, now representing approximately 90% of MRSA infections in cutaneous and subcutaneous tissue in children.1,2 Children in daycare and athletes are some of the persons at higher risk, but most patients are young, healthy, and immunocompetent.1 When diagnosing and treating in fections caused by S aureus, the possibility of MRSA must be considered, particularly when standard treatment is not efficacious. See Chapter 284 for more information regarding MRSA and treatment considerations. Anaerobic bacteria are a less common cause of impetigo. In general, intact skin is resistant to impetiginization, and some form of compromise of the epidermal surface is necessary to permit infection. Predisposing factors include minor abrasions and lacerations, arthropod bites, burns, varicella, and several types of dermatitis, especially atopic dermatitis. Exposed areas such as the face, arms, and legs are most commonly affected, and impetigo is most common during the summer months.

Table 367-1. Topical Antibacterial Therapies

Impetigo usually presents in one of two clinical forms. Nonbullous (crusted) impetigo, which accounts for more than 70% of cases, begins with small vesicles or vesiculopustules that rupture rapidly, leaving behind a honey-colored crust superimposed on a moist red base. Lesions are minimally symptomatic, although mild pain or pruritus may be present. Autoinoculation of the infection from scratching or digital manipulation may result in the spread of lesions. Associated findings include lymphadenopathy in 90% of patients, and leukocytosis, in up to 50% of cases.

Bullous impetigo is caused by infection with a toxin-producing strain of S aureus, primarily by phage group 2 or type 71, and less commonly types 3A, 3B, 3C, and 55. The initial lesions consist of flaccid bullae that rupture easily given the superficial, subcorneal location of lysis caused by the action of the toxin on the epidermis. Patients usually present with shallow, moist, erythematous erosions with a surrounding collarette of residual blister roof (Fig. 367-1). Even in the absence of intact bullae, the clinical lesions are usually quite diagnostic. Lesions of bullous impetigo may have a propensity for moist, intertriginous areas such as the diaper region, axillae, and neck folds.

Figure 367-1. Bullous impetigo. Note ruptured lesions with a collarette of scale.

FOLLICULITIS

FOLLICULITIS

Folliculitis is a superficial infection of the pilosebaceous unit, most typically caused by S aureus. Patients present with erythematous papules and papulopustules centered around hair follicles (Fig. 367-2) that are most often distributed over the scalp, thighs, and/or buttocks. Warmth, moisture, and maceration predispose to folliculitis, and many cases therefore occur during the warmer summer months. Treatment is with both topical antibacterial therapy and systemic antibiotics when more severe.

There are a variety of other types of folliculitis. Gram-negative folliculitis, most often caused by Klebsiella, Enterobacter, or Proteus, may be seen in patients with acne vulgaris on oral antibiotic therapy. In these patients, lesions are most common in the facial “T zone.” Another form of gram-negative folliculitis, Pseudomonas (hot tub) folliculitis, occurs within a few days of exposure to a poorly chlorinated whirlpool or hot tub. These lesions are most common over the buttocks, legs, and arms and may be accompanied by mild constitutional symptoms such as fever and malaise. Immunocompromised patients may develop folliculitis from normally nonpathogenic organisms such as Pityrosporum or the hair follicle mite, Demodex. Noninfectious forms of folliculitis may also occasionally occur. Sterile folliculitis may occur as a result of the frequent application of exogenous agents such as hair gels, which obstruct the orifice of the pilosebaceous unit. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis occurs as recurrent pruritic follicular papules and pustules, especially on the scalp and forehead of infants. These pustules are sterile and reveal clusters of eosinophils. A similar entity has been described in adult patients with HIV infection. In pediatric patients, this is not the case, and the diagnosis as a distinct entity has more recently been questioned.6,7

OTHER SUPERFICIAL INFECTIONS

OTHER SUPERFICIAL INFECTIONS

Furuncles and Carbuncles More deeply seated infections of the pilosebaceous unit are termed furuncles and carbuncles and are usually caused by S aureus. Patients with furuncles present with erythematous, painful, fluctuant nodules (abscesses). A carbuncle is a collection of furuncles that is multiloculated and composed of interconnecting sinuses. Incision and drainage of these lesions is necessary in addition to antibiotic therapy, particularly for MRSA abscesses.1

Noninfectious causes of abscesses include those associated with acne vulgaris (as a result of follicular rupture and a brisk inflammatory reaction), those in response to a foreign body in the skin, or those that follow spontaneous rupture of an epidermal cyst. “Cold” abscesses, which are only mildly erythematous and tender, may be seen in individuals with the hyper-immunoglobulin-E (hyper IgE) syndrome.

Perianal Streptococcal Cellulitis This infection occurs predominantly in children ages 6 months to 10 years and is caused most often by GABHS, and occasionally by S aureus. It is characterized by sharply circumscribed, bright red perianal erythema, which may be accompanied by pruritus, anal fissures, constipation, and pain on defecation. Blood-streaked stools and purulent anal discharge may be present, although systemic symptoms are rare. Because similar signs and symptoms are seen with other more common dermatologic conditions, diagnosis is frequently delayed. Flares of guttate psoriasis may be associated with perianal streptococcal cellulitis; hence, perianal examination is recommended in all patients with this presentation. Perianal streptococcal cellulitis may be confirmed with a bacterial culture.8,9

Blistering Dactylitis Patients present with bullae on an erythematous base, usually distributed over the volar fat pad of distal phalanges (Fig. 367-3), occasionally with dorsal finger or palmar involvement. More than one digit is usually involved. Gram stain and bacterial culture of blister fluid often reveals GABHS, but S aureus has more recently been found to be more common,10 and group B streptococci can sometimes be found. The intact blisters in blistering dactylitis, an unusual feature of streptococcal-mediated skin infections, are likely related to the thickness of the stratum corneum in the volar sites to which this condition is usually localized.11

Figure 367-2. Folliculitis. Erythematous papules and papulopustules surround hair follicles.

Figure 367-3. Blistering dactylitis. Note erythema with a bulla over the volar fat pad.

Acute Paronychia This common infection of the skin surrounding the nail, presents with erythema, edema, and tenderness of both the proximal and lateral nail folds. Small pustules or abscesses may also be present around the base of the nail. Predisposing conditions include trauma, dermatitis, frequent hand washing, and onychophagia (nail biting). S aureus is most commonly isolated, although mixed infection, including anaerobic organisms, may be present. In addition to antimicrobial therapy directed against S aureus, incision and drainage may be necessary.

Corynebacteria Skin Infection Erythrasma is a superficial skin infection, primarily occurring in intertriginous zones, caused by Corynebacteria minutissimum. The clinical presentation is characterized by slightly red to tan patches with mild scaling, in the toe webs, axillae, inframammary creases, groin, or gluteal crease. Lesions are asymptomatic to mildly pruritic and may be confused with cutaneous fungal infections. Wood’s lamp examination is helpful in confirming the diagnosis and reveals coral red fluorescence, related to the production of porphyrin compounds by the corynebacteria.

Pitted keratolysis is also caused by corynebacteria and presents with plantar hyperhidrosis, burning, foul odor, and small punctate pits. It is seen most commonly in males with a history of prolonged use of occlusive footwear (ie, military personnel, athletes), especially in warm, damp environments.

BACTERIAL INFECTIONS EXTENDING INTO THE DERMIS AND SUBCUTANEOUS TISSUES

ECTHYMA CONTAGIOSUM

ECTHYMA CONTAGIOSUM

This disorder is caused primarily by the combination of group A β-hemolytic streptococci (GABHS) and S aureus, is a deep cutaneous infection that extends through the epidermis into the dermis. An impetiginous crust enlarges and on removal reveals an underlying punched-out ulcer, which may be filled with purulent material. The most common sites of involvement are the lower legs; if left untreated, ecthyma may progress to cellulitis or lymphangitis. Healing takes place with scar formation. Ecthyma gangrenosum is a cutaneous manifestation of sepsis with Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Patients are usually systemically ill and have an underlying illness such as hematologic malignancy or immunodeficiency, but a number of healthy children have also been described.12 They present with 0.5- to 2-cm hemorrhagic papules, nodules, bullae, or ulcers, usually distributed in the genital region. These lesions rapidly progress to necrosis and eschar formation. The organism can be cultured from swabs of the lesions or biopsy tissue, and blood cultures are positive. Therapy with intravenous antibiotics must be rapidly initiated. Occasionally, other organisms (ie, other gram-negative bacteria, Candida, Aspergillus, Fusarium) may cause ecthyma gangrenosum–like lesions, and treatment should be directed accordingly.13

CELLULITIS

CELLULITIS

Cellulitis is an acute infection of the subcutaneous tissues that may be caused by many different bacterial organisms. GABHS and S aureus are again the most common etiologic agents, and the lower extremities and feet are the locations most often affected. There is frequently a history of a predisposing break in the skin barrier, such as that caused by atopic dermatitis, contact dermatitis, inflammatory tinea pedis, or trauma. Associated fever, malaise, and chills may be present. In the absence of preexisting skin lesions or in the presence of fever or systemic symptoms, bacteremia should be considered, especially in very young children.

Erysipelas is a superficial form of cellulitis that presents with marked redness and pain in the affected area and often demonstrates well-demarcated, elevated borders. There may be a history of a fissured dermatitis, ulcer, or puncture wound, and GABHS is the most common etiologic agent. Although the diagnosis of both cellulitis and erysipelas is usually suggested on clinical grounds, fine-needle aspiration with Gram stain and culture may be useful in patients with immunocom-promise or a suboptimal response to therapy.

Preseptal (periorbital) cellulitis is a form of cellulitis that involves the periorbital skin and soft tissues. It must be differentiated from orbital cellulitis, a potentially sight-threatening emergency that can occur from direct extension of preseptal cellulitis through the orbital septum, hematogenous seeding, or direct extension from infected paranasal sinuses. Preseptal cellulitis presents with erythema and edema, which tends to be fairly well demarcated. If decreased ocular movement or proptosis is present, orbital cellulitis must be considered and should be evaluated with radiologic imaging, along with consultation by ophthalmologic colleagues. Although Haemophilus influenzae type B (HiB) has traditionally been the most frequently implicated etiologic agent, the advent of the HiB vaccine has greatly decreased the incidence, of many HiB-associated childhood diseases, including preseptal and orbital cellulitis. Other organisms, especially Streptococcus spp, are now a more frequent cause of preseptal and orbital cellulitis. Prompt institution of intravenous antibacterial therapy is critical for a favorable outcome.14

NECROTIZING FASCIITIS

NECROTIZING FASCIITIS

This is a rare, rapidly progressive, and potentially fatal soft tissue infection that develops at the level of the superficial fascia and often involves the overlying dermis, which may result in the incorrect initial diagnosis of cellulitis. Deep fascia and muscle are spared in most cases, although circumferential involvement may lead to compartment syndrome. A penetrating or blunt traumatic skin injury can be the source of the bacterial infection. Polymicrobial infection with a mix of aerobic and anaerobic organisms, including group A streptococcus, S aureus, Escherichia coli, Bacteroides (spp), Peptostreptococcus (spp), Clostridium (spp), and Pseudomonas aeruginosa,15 are the usual etiologic agents. Patients usually present with erythema, swelling, along with exquisite tenderness and pain, usually in an extremity. Anesthesia of the overlying skin may aid in the differentiation from cellulitis. Bullae may develop that become hemorrhagic with eventual necrosis and frank cutaneous gangrene with crepitance. Fever is present in most patients. Patients with invasive GABHS infection may develop associated toxic shock syndrome. Soft tissue gas on plain radiography may be present. Although MR or CT imaging, fine-needle aspiration, and tissue biopsy may be helpful in making the diagnosis, direct surgical inspection of fascia is the fastest and most sensitive technique. Aggressive surgical debridement, parenteral antimicrobial therapy, fluid replacement, and blood pressure support are crucial in the treatment of patients with necrotizing fasciitis. Mortality is high, ranging from 30% to 70%.16

VIRAL INFECTIONS

WARTS

WARTS

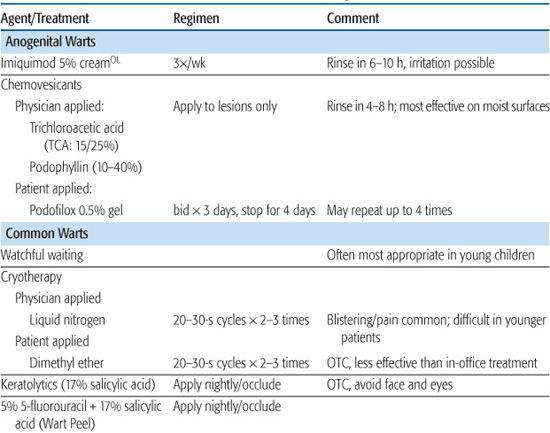

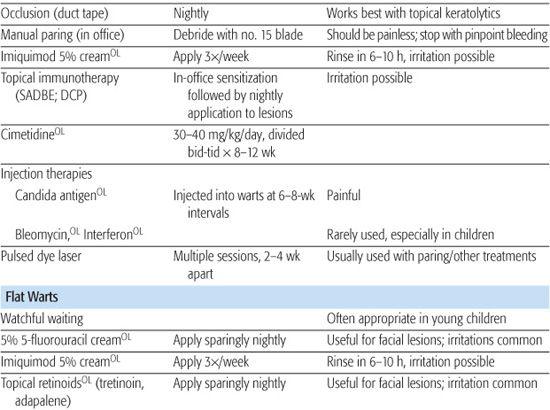

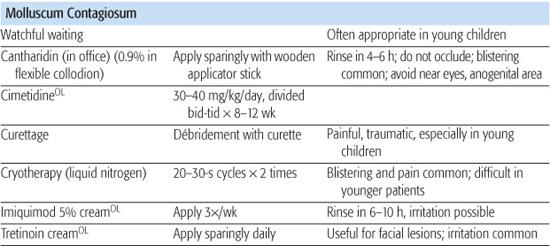

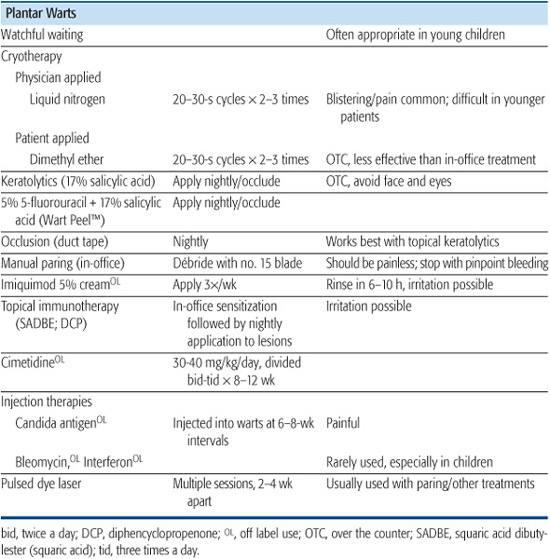

An extremely common condition in children, verrucae (warts) are caused by infection of the squamous epithelium of skin or mucous membranes with the human papillomavirus (HPV). More than 80 subtypes of HPV have now been described; different types may reveal specific tropisms for distinct cell types. For example, HPV types 1, 2, 4, and 7 are associated with plantar, palmar, and common warts; types 3, 10, and 28 with flat warts; and types 6, 11, 16, 18, 31, and 33 with anogenital and genital tract warts and tumors. Treatments for warts and molluscum contagiosum are outlined in Table 367-2.

Table 367-2. Treatments for Warts and Molluscum Contagiosum

Common warts (verruca vulgaris) can be found on all body surfaces. Frequent locations are the fingers, periungual regions, palms, and soles (see discussion on plantar warts that follows). They present as flesh-colored, hyperkeratotic papules, which may be solitary or multiple. Filiform lesions may occur and are characterized by a slender stalk with numerous projections distally. Tiny black dots representing thrombosed capillaries may be visualized centrally, especially after manual debridement of devitalized tissue, and may be a useful diagnostic clue. Autoinoculation, presenting as lesions in a linear array, may be related to scratching and manual dissemination of the virus. Spontaneous wart regression occurs in up to 85% of lesions within 2 years and is believed to be related to cell-mediated immune processes. Specific anti-HPV therapies are lacking, and most effective treatments rely on mechanical destruction of infected tissues and the resultant inflammatory response. Excessively traumatic procedures (especially in the pediatric patient) or those that result in scarring are unwarranted in the treatment of warts.

Plantar warts occur most often on weight-bearing portions of the soles and may induce significant hyperkeratosis (or epidermal thickening) with resultant pain on ambulation. Manual debridement of the hyperkeratotic surface by paring with a scalpel blade again reveals thrombosed capillaries, which may help differentiate them from corns and calluses and relieve discomfort. Therapy of plantar warts is difficult given their location and endophytic nature, which is a result of weight bearing.

Flat warts present as small (1- to 10-mm), flat, flesh-colored to pink papules and are most commonly distributed on the face (Fig. 367-4), dorsal hands, and arms. No hyper-keratosis or scale is present. Treatment is usually unnecessary.17

Condylomata acuminata (anogenital warts) are more common in sexually active adolescents, but may occur in infants and prepubertal children as well. The importance of identifying anogenital warts in the pediatric patient lies in the possible association with a sexual mode of transmission and sexual abuse. However, it is well recognized that benign modes of transmission can result in pediatric anogenital warts, and their presence is not pathognomonic of sexual abuse. Nonsexual modes of transmission may occur, especially in children younger than 3 years and may include innocent heteroinoculation, autoinoculation, or vertical transmission from passage through an infected birth canal. They present as flesh-colored papules in perianal, genital, and perigenital tissues. Anogenital warts may be caused by genital HPV types, such as 6, 11, 16, or 18, or by uncommon HPV types, such as type 2, but HPV type cannot be differentiated on the basis of appearance.18,19 Given the association of certain genital HPV types with anogenital carcinomas and the uncertain prognostic significance in children, periodic follow-up for anogenital dysplasia is suggested. The American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Child Abuse and Neglect considers condylomata acuminata in infants (if not perinatally acquired) and prepubertal children “suspicious” for sexual abuse and recommends reporting to the appropriate child protective agency.20

Figure 367-4. Flat warts (verruca plana). Numerous white-pink, flat-topped papules on the forehead, showing evidence of the Koebner phenomenon.

MOLLUSCUM CONTAGIOSUM

MOLLUSCUM CONTAGIOSUM

The lesions of molluscum contagiosum, a common skin infection caused by a poxvirus, are most common in children, particularly those with a history of atopic dermatitis,21 although they may also occur in adults as a sexually transmitted disease or in association with immuno-suppression. They are transmitted via skin-to-skin contact or autoinoculation and occasionally by fomites. Molluscum may occur at any site, but are most often seen on the inner thighs, popliteal or antecubital fossae, axillae, and abdomen. Individual lesions are flesh-colored, pearly, dome-shaped papules that may have a central umbilication and usually range in size between 1 and 5 mm (Fig. 367-5). Associated inflammation and scaling, so-called molluscum dermatitis, can be severely pruritic and improves with topical corticosteroids. The natural course of molluscum contagiosum is one of spontaneous involution, although the timing is unpredictable, and lesions may become numerous or symptomatic, necessitating therapy.

HERPES VIRUS INFECTIONS

HERPES VIRUS INFECTIONS

Infections with herpes simplex virus (HSV), a member of the Herpesviridae family, range from a mild illness (common cold sores or gingivostomatitis) to severe or life-threatening involvement (encephalitis). There are two serologic subtypes of HSV: type 1 (HSV-1) and type 2 (HSV-2). Infections of the oral cavity are most commonly due to HSV-1 and may be spread to the face, conjunctivae, or cornea. Beyond the neonatal period, encephalitis is virtually always caused by HSV-1. Infection with HSV-2 in childhood may be indicative of, but is not pathognomonic for, sexual abuse. HSV infections in the neonate are usually acquired via passage through an infected birth canal and may be limited to skin, eyes, and mucosa (SEM disease) or may be more severe and involve the central nervous system or have multiple organ dissemination. HSV-2 causes approximately 75% of these illnesses. Neonatal HSV is discussed in more detail in Chapter 309.

The treatment of choice for cutaneous HSV infection is acyclovir, which is available in a suspension containing 200 mg/tsp (5 ml). Although information regarding pediatric dosing is limited, 200 mg five times a day seems effective for children older than 2 years. The decision regarding therapy of HSV is based on several factors, including severity, symptomatology, frequency of recurrences, and immune status of the patient.

Gingivostomatitis is the most common clinical manifestation of primary HSV infection in young children.22 It is most commonly seen between the ages of 9 months and 3 years and, although self-limited over 10 to 14 days, may be associated with extreme discomfort, fever, refusal to drink, and dehydration. Malaise, irritability, and lymphadenopathy may also be present. Small vesicles or erosions on an erythematous base over the gingiva, palate, lips, and tongue is the usual presentation. Grouped vesicles or erosions on an erythematous base may be present in the perioral area. Treatment is primarily symptomatic, with analgesics, antipyretics, and fluids. Oral acyclovir, if initiated within the first 3 days of illness, can help decrease the symptomatology.23

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree