21.1 Skin disorders

Neonatal skin conditions

Pustular lesions in the neonate

Sterile benign transient pustular disorders

• Toxic erythema of the newborn – widespread red macules each surmounted by a papule or pustule; onset in the first 2 days of life and disappearance by the end of the first week.

• Transient neonatal pustular dermatosis – onset at birth of flaccid pustules that dry out in 48 hours, leaving post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation in dark-skinned infants.

• Infantile acropustulosis – crops of spontaneously resolving pustules on the hands and feet that occur during the first few months of life.

• Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis of the scalp – recurrent groups of pustules on a red base on the scalp in early infancy; later they may occur elsewhere.

• Pustular miliaria or sweat duct occlusion rash – short-lived pustules in amongst more typical red papules of miliaria (heat rash), occurring particularly on the face, scalp and upper trunk.

Infective disorders presenting with pustules

• Staphylococcal infection – particularly impetigo (which more often presents with vesicles); a common site is near an infected umbilical stump.

• Candida – multiple widespread small pustules which soon rupture producing a circular lesion with peripheral scale.

• Herpes simplex – grouped, often coalescing, pustules; often evolve from initial vesicular lesions. Particularly on presenting part (so usually the head). This may be associated with severe neurological disease (see below and also Chapter 11.4).

• Varicella – usually initially vesicles, which may become pustular. Unlike chickenpox in older children, the lesions are often seen in the same stage of development.

• Many other organisms including Listeria monocytogenes, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Haemophilus influenzae can cause sepsis and pustules.

Blistering lesions in the neonate

Infections

• Herpes simplex – grouped coalescing vesicles, particularly on presenting part (so usually the head); rupture to produce deep, punched out, erosions.

• Varicella – usually initial vesicles which soon evolve into pustules.

• Bullous impetigo – flaccid blisters which soon rupture to produce large superficial spreading erosions (Fig. 21.1.1).

• Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome – widespread erythema followed by superficial erosions, commencing in flexural areas and around the mouth; may be transient blistering.

Conditions with possible systemic implications

• Zinc deficiency – blistered and crusted lesions around mouth, nose and in napkin area.

• Epidermolysis bullosa – blistering in areas of trauma; may be mucosal blistering and breathing problems.

• Bullous ichthyosis – blisters and erosions on the base of a bright red skin; skin thickens in early days.

• Mastocytosis – blisters on the background of localized brownish lesions or a diffuse leathery skin with a peau d’orange appearance.

• Langerhans cell histiocytosis – vesicles, erosions and purpuric crusted lesions (Fig. 21.1.2); may be self-limiting or can progress to, or reappear as, a serious malignant disease. May be associated lytic bone lesions and hepatomegaly.

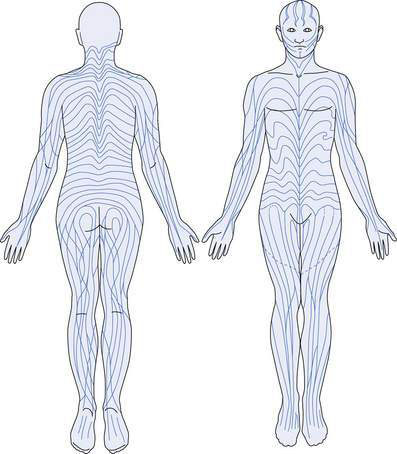

• Incontinentia pigmenti – a linear arrangement of blisters, particularly on the limbs (Fig. 21.1.3), following the lines of Blaschko (see below). An X-linked recessive disease, so presents predominantly in girls. The mother may have late stigmata of disease, including brown Blaschko-distributed lesions, patchy alopecia and partial anodontia. Infant may have early seizures.

Purpura in the neonate

• Systemic congenital infections – including rubella, cytomegalovirus, toxoplasmosis, herpes simplex.

• Haemolytic disease of the newborn – for example with Rhesus incompatibility.

• Malignancy – including neuroblastoma, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, leukaemia.

• Iatrogenic injury – including birth trauma, extravasation of drugs, arterial injury during catheterization.

Red, scaly rashes in the neonate or young infant

• Seborrhoeic dermatitis – dull red erythema with a greasy, yellow scale involving particularly the scalp, centrofacial area and all flexures, major and minor. The scale may be absent in the flexures, and secondary monilia is common. Usually asymptomatic and self-limiting after the early months of life. Responds to weak steroids and anti-monilial agents. In cases in which there is a failure to respond to appropriate treatment, or the presence of any brownish scale or purpura, the possibility of Langherhans cell histiocytosis, which also occurs in the ‘seborrhoeic areas’, must be considered.

• Atopic dermatitis – rarely this condition presents in very early infancy with a widespread red, scaly and itchy rash. These patients often have food allergies and will go on to develop difficult long-term disease.

• Ichthyoses – some of these conditions present with the child covered in a shiny, red membrane that peels off in the early weeks of life to leave a red scaly skin. Some commence with a dramatic degree of redness and scale without the membrane. An early possible complication is hypernatraemic dehydration. The high metabolic state may lead to failure to thrive. Some are associated with neurological abnormalities.

• Metabolic disorders – a red, scaly rash can occur in neonates with inherited carboxylase deficiencies and essential fatty acid deficiency secondary to any severe malabsorption. The former may be associated with severe acidosis and coma.

• Immunodeficiencies – patients with severe combined immune deficiency (SCID) and other immunodeficiencies may present with a widespread, red, scaly rash in the neonatal period or early infancy. In some cases this represents a congenital graft-versus-host disease.

• Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome – after the blistering and erosive phase there may be a striking scaly and crusted rash, still on a residual erythematous background.

• Congenital candidiasis – usually presents with small pustules, but as they resolve a widespread scaly red rash can ensue.

Birthmarks and other naevoid conditions

Pigmented birthmarks

Congenital melanocytic naevi (CMN)

These occur at birth as raised verrucous or lobulated lesions of varying shades of brown to black, sometimes with blue or pink components, with an irregular margin and often growing long dark hairs. They may become increasingly hairy with time. Giant-sized lesions may produce considerable redundancy of skin and often occur in a ‘garment’ distribution on the trunk and adjacent limbs. In patients with large naevi an eruption of smaller, but essentially similar, lesions may occur during the first few years of life. Malignancy in giant naevi can occur in childhood and the incidence over a lifetime is possibly of the order of 2%. In medium and small lesions the risk is much lower and any development of malignancy is always post-pubertal. When large lesions occur over the axial spine, and in particular when multiple satellite lesions are present, there is a risk of intracranial lesions, both melanocytic involving the meninges and structural in the posterior cranial fossa, which may be further complicated by obstructive hydrocephalus. CMN over the lower spine may be associated with a tethered cord (Fig. 21.1.4). Neuroimaging is required in all these patients.

Naevoid pigmentary disorders

These are flat areas of hyperpigmented or hypopigmented skin, obvious at or very soon after birth. They occur in characteristic patterns – either segmental, or whorled and streaky following the lines of Blaschko (Fig. 21.1.5). These lines represent the tracks taken by genetically identical cells in the embryo and are a marker for genetic mosaic patterns. The lesions usually have rather irregular edges. Sometimes the condition is extensive, resembling a marble cake, and both hypopigmented and hyperpigmented lesions are present in the one individual. These lesions usually occur as isolated phenomena but may be associated, as part of certain mosaic phenotypes, with neurological, skeletal and other abnormalities. One syndrome with hyperpigmented lesions and skeletal abnormalities is McCune–Albright syndrome.

Epidermal naevi

Epidermal naevi arise from the basal layer of the embryonic epidermis, which gives rise to skin appendages as well as keratinocytes. These naevi have been classified, according to the tissue of origin, into keratinocytic, sebaceous and follicular types. They can involve any area of skin. They may be present at birth or appear in the first few years of life; subsequently they may simply grow with the patient or new areas of involvement may become evident. On the scalp and face the naevi have a yellowish colour, due to prominent sebaceous glands, and present as a hairless, often linear, plaque, usually flat in infancy and childhood and becoming verrucous at puberty. Lesions elsewhere are usually dark brown but are occasionally paler than the normal skin. They occur as single or multiple warty plaques or lines, often arranged in a linear or swirled pattern (Fig. 21.1.6).

Vascular birthmarks

Haemangiomas

Presentation and terminology

• Superficial haemangiomas usually appear in the first weeks of life as an area of pallor, followed by a telangiectatic patch. They then grow rapidly into a lobulated, well demarcated, bright red tumour. Rapid growth continues over the first 6 months of life; the growth rate then slows and further growth after 10 months is unusual. After a stationary phase, signs of involution begin, with the appearance of grey areas that enlarge and coalesce. The tumour becomes softer and less bulky and then disappears in 90% of cases by 9 years of age. Residual skin changes at the site may persist.

• Deeper haemangiomas may occur alone or beneath a superficial lesion (Fig. 21.1.7). The overlying skin is normal or bluish in colour. As they resolve, they soften and shrink, and most disappear completely.

Complications of haemangiomas

Although many haemangiomas resolve without sequelae, significant complications can occur.

• Incomplete resolution – redundant tissue, residual telangiectasia, scarring following ulceration.

• Ulceration – inevitable scarring, full-thickness tissue loss on ‘edge structures’ (lip, lid, ala), cicatricial ectropion from scarring of eyelids, cicatricial alopecia.

• Obstruction of vital structures:

Possible associations of haemangiomas

• Lumbosacral lesions – tethered spinal cord.

• Perineal segmental lesions – abnormalities of the genitalia and lower urogenital and gastrointestinal tracts.

• Large segmental facial lesions – posterior cranial fossa malformations, abnormalities of heart, aorta and other major arteries, and ocular abnormalities.

• Multiple small cutaneous haemangiomas – haemangiomas in the liver, brain and other internal organs; high-output cardiac failure.

Appropriate imaging studies should be performed in all patients with these presentations.

Moles (acquired melanocytic naevi)

Halo naevi

A depigmented halo may occur around a melanocytic naevus; the lesion may appear inflamed and often disappears, leaving a white spot, which may eventually repigment. This is a completely benign change. Although often apparently isolated, the condition can occur in the setting of vitiligo (Fig. 21.1.8) and may in some patients indicate a predisposition to this condition.

Cutaneous infections and infestations

Viral exanthems

• specific – where the appearance of the exanthem enables a clinical diagnosis of the causative virus.

• non-specific – where the same pattern of exanthem may be caused by many different viruses.

Specific patterns

• Chickenpox – scattered vesicles, pustules and dark crusts; lesions occur in crops (see Chapter 12.1).

• Herpes zoster – vesicles and pustules following the distribution of sensory nerves (see Chapter 12.1).

• Erythema infectiosum – caused by a parvovirus B19, presenting with a slapped cheek appearance followed by a lacy erythematous rash mainly on the limbs (Fig. 21.1.9) (see Chapter 12.1).

• Mollusca – caused by a pox virus (see below).

• Hand, foot and mouth disease – due to one of the Coxsackie group of enteroviruses; presents with pustules and purpuric lesions limited to hands and feet with oral blistering.

Non-specific patterns

The viruses usually involved are:

• Human herpesvirus (HHV) 6 and HHV7

• Parvovirus (can produce non-specific as well as specific rashes).

• Urticarial exanthems – raised erythematous lesions that may be annular or figurate; itch is variable and the pattern changes from hour to hour. In young children there may be a central non-palpable purpuric element that resolves over several days rather than hours, leading to misdiagnosis as erythema multiforme. In children under 6 years old, more than 90% of cases of urticaria are caused by a viral illness.

• Macular exanthems – these are composed of flat red spots of variable size, sometimes becoming confluent. These are usually widespread and are characteristically difficult to differentiate from allergic reactions to drugs. In general the occurrence of lesions in a linear distribution along scratch marks, exaggeration in areas of sunburn or previous skin disease, and the presence of lymphadenopathy favour a viral over a drug aetiology.

• Papular exanthems – papules, which are raised erythematous lesions, may be few or multiple and vary in size from tiny pinpoint lesions to 0.5–1.0 cm in diameter. A linear distribution of groups of lesions is commonly seen and the limbs are usually affected more than the trunk.

• Purpuric exanthems – enteroviruses are the commonest causes of purpuric exanthems. Clearly the most important condition to be differentiated is meningococcal septicaemia. The purpuric lesions caused by enteroviruses tend to be small petechial macules but larger, angulated lesions sometimes occur.

• Vesicular and/or pustular exanthems – these lesions start as vesicles but often, as in varicella, become pustular and an admixture of lesions is seen. The lesions are often concentrated mainly on the limbs. The buttocks are another common site of involvement.

• Erythrodermic exanthems – these are rare, with widespread erythema and variable scaling. They are particularly difficult to differentiate from bacterial toxic reactions and drug reactions.

Conditions that may mimic viral exanthems, or which viral exanthems may mimic, include:

• Drug reactions – urticarial, macular, papular or erythrodermic exanthems. History of exposure and timing are helpful in differentiation. An allergic reaction to ampicillin is more common in patients with Epstein–Barr virus infection.

• Kawasaki disease – macular, urticarial, erythrodermic exanthems. An erythematous rash accompanied by oedema of the palms and soles is often prominent in Kawasaki disease. Other early features include prolonged high fever, conjunctivitis, redness, swelling or ulceration of mucosal surfaces, and enlargement of lymph nodes. Desquamation of the hands and feet, especially of the digit tips, is a later finding.

• Meningococcal septicaemia – purpuric exanthem (see Chapter 12.3). Small purpuric spots and larger stellate areas of purpura developing central necrosis. Associated with high fever and shock.

• Scarlet fever – papular exanthem, erythrodermic exanthem. There is significant fever, strawberry tongue, a rough consistency to the rash, and later peeling of palms and soles.

• Staphylococcal and streptococcal toxic shock – erythrodermic exanthems. Accompanied by a high fever and significant manifestations of shock.

• Rickettsial infections – macular, papular or purpuric exanthems.

• Miliaria or heat rash – micropapular exanthem or purpuric exanthem in a thrombocytopenic child with miliaria.

• Systemic juvenile chronic arthritis – macular, papular and urticarial exanthems. An erythematous maculopapular rash is often seen in this condition. This rash usually has a salmon-pink colour and tends to come and go, being particularly evident at the time when the fever is at its height. It may also be urticarial.

• Food-induced urticaria – urticarial exanthems.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree