TREATMENT OF SKIN DISORDERS

Topical Therapy

Treatment should be simple and aimed at preserving normal skin physiology. Topical therapy is often preferred because medication can be delivered in optimal concentrations to the desired site.

Water is an important therapeutic agent, and optimally hydrated skin is soft and smooth. This occurs at approximately 60% environmental humidity. Because water evaporates readily from the cutaneous surface, skin hydration (stratum corneum of the epidermis) is dependent on the water concentration in the air, and sweating contributes little. However, if sweat is prevented from evaporating (eg, in the axilla, groin), local humidity and hydration of the skin are increased. As humidity falls below 15%–20%, the stratum corneum shrinks and cracks; the epidermal barrier is lost and allows irritants to enter the skin and induce an inflammatory response. Decrease of transepidermal water loss will correct this condition. Therefore, dry and scaly skin is treated by using barriers to prevent evaporation (Table 15–2). Oils and ointments prevent evaporation for 8–12 hours, so they must be applied once or twice a day. In areas already occluded (axilla, diaper area), creams or lotions are preferred, but more frequent application may be necessary.

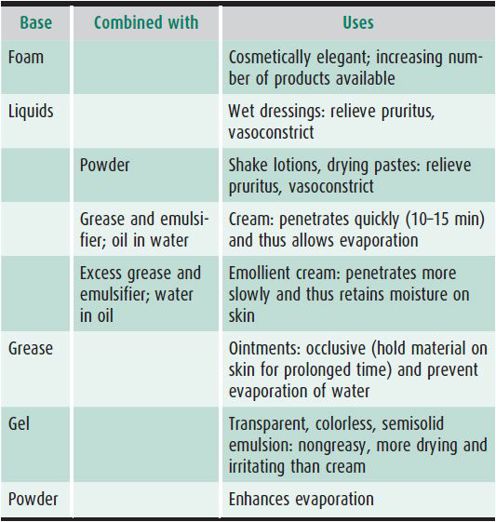

Table 15–2. Bases used for topical preparations.

Overhydration (maceration) can also occur. As environmental humidity increases to 90%–100%, the number of water molecules absorbed by the stratum corneum increases and the tight lipid junctions between the cells of the stratum corneum are gradually replaced by weak hydrogen bonds; the cells eventually become widely separated, and the epidermal barrier falls apart. This occurs in immersion foot, diaper areas, axillae, and the like. It is desirable to enhance evaporation of water in these areas by air drying.

Wet Dressings

By placing the skin in an environment where the humidity is 100% and allowing the moisture to evaporate to 60%, pruritus is relieved. Evaporation of water stimulates cold-dependent nerve fibers in the skin, and this may prevent the transmission of the itching sensation via pain fibers to the central nervous system. It also is vasoconstrictive, thereby helping to reduce the erythema and also decreasing the inflammatory cellular response.

The simplest form of wet dressing consists of one set of wet underwear (eg, long johns) worn under dry pajamas. Cotton socks are also useful for hand or foot treatment. The underwear should be soaked in warm (not hot) water and wrung out until no more water can be expressed. Dressings can be worn overnight for a few days up to 1 week. When the condition improves, wet dressings are discontinued.

Topical Glucocorticoids

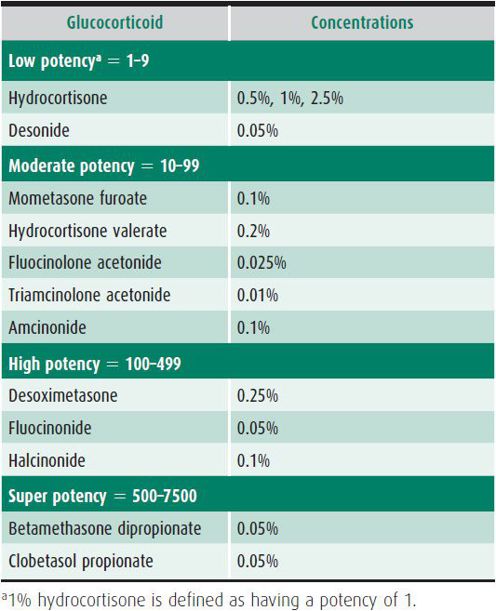

Twice-daily application of topical corticosteroids is the mainstay of treatment for all forms of dermatitis (Table 15–3). Topical steroids can also be used under wet dressings. After wet dressings are discontinued, topical steroids should be applied only to areas of active disease. They should never be applied to normal skin to prevent recurrence. Only low-potency steroids (see Table 15–3) are applied to the face or intertriginous areas.

Table 15–3. Topical glucocorticoids.

Bewley A; Dermatology Working Group: Expert consensus: time for a change in the way we advise our patient to use topical corticosteroids. Br J Dermatol 2008;158:917 [PMID: 18294314].

Devillers AC, Oranje AP: Efficacy and safety of “wet wrap” dressings as an intervention treatment in children with severe and/or refractory atopic dermatitis: a critical review of the literature. Br J Dermatol 2006;154:579 [PMID: 16536797].

Nolan K, Marmur E: Moisturizers: reality and the skin benefits. Dermatol Ther 2012 May–Jun;25(3):229–233.

Characteristics of bases for topical preparations:

1. Thermolabile, low-residue foam vehicles are cosmetically acceptable and use a novel permeability pathway for delivery.

2. Most greases are triglycerides (eg, Aquaphor, petrolatum, Eucerin).

3. Oils are fluid fats (eg, Alpha Keri, olive oil, mineral oil).

4. True fats (eg, lard, animal fats) contain free fatty acids that cause irritation.

5. Ointments (eg, Aquaphor, petrolatum) should not be used in intertriginous areas such as the axillae, between the toes, and in the perineum, because they increase maceration. Lotions or creams are preferred in these areas.

6. Oils and ointments hold medication on the skin for long periods and are therefore ideal for barriers, prophylaxis, and for dried areas of skin. Medication penetrates the skin more slowly from ointments.

7. Creams carry medication into skin and are preferable for intertriginous dermatitis.

8. Foams, solutions, gels, or lotions should be used for scalp treatments.

DISORDERS OF THE SKIN IN NEWBORNS

TRANSIENT DISEASES IN NEWBORNS

1. Milia

Milia are tiny epidermal cysts filled with keratinous material. These 1- to 2-mm white papules occur predominantly on the face in 40% of newborns. Their intraoral counterparts are called Epstein pearls and occur in up to 60%–85% of neonates. These cystic structures spontaneously rupture and exfoliate their contents.

2. Sebaceous Gland Hyperplasia

Prominent white to yellow papules at the opening of pilosebaceous follicles without surrounding erythema—especially over the nose—represent overgrowth of sebaceous glands in response to maternal androgens. They occur in more than half of newborns and spontaneously regress in the first few months of life.

3. Neonatal Acne

Inflammatory papules and pustules with occasional comedones predominantly on the face occur in as many as 20% of newborns. Although neonatal acne can be present at birth, it most often occurs between 2 and 4 weeks of age. Spontaneous resolution occurs over a period of 6 months to 1 year. A rare entity that is often confused with neonatal acne is neonatal cephalic pustulosis. This is a more monomorphic eruption with red papules and pustules on the head and neck that appears in the first month of life. There is associated neutrophilic inflammation and yeasts of the genus Malassezia. This eruption will resolve spontaneously, but responds to topical antiyeast preparations.

4. Harlequin Color Change

A cutaneous vascular phenomenon unique to neonates in the first week of life occurs when the infant (particularly one of low birth weight) is placed on one side. The dependent half develops an erythematous flush with a sharp demarcation at the midline, and the upper half of the body becomes pale. The color change usually subsides within a few seconds after the infant is placed supine but may persist for as long as 20 minutes.

5. Mottling

A lacelike pattern of bluish, reticular discoloration representing dilated cutaneous vessels appears over the extremities and often the trunk of neonates exposed to lowered room temperature. This feature is transient and usually disappears completely on rewarming.

6. Erythema Toxicum

Up to 50% of full-term infants develop erythema toxicum. At 24–48 hours of age, blotchy erythematous macules 2–3 cm in diameter appear, most prominently on the chest but also on the back, face, and extremities. These are occasionally present at birth. Onset after 4–5 days of life is rare. The lesions vary in number from a few up to as many as 100. Incidence is much higher in full-term versus premature infants. The macular erythema may fade within 24–48 hours or may progress to formation of urticarial wheals in the center of the macules or, in 10% of cases, pustules. Examination of a Wright-stained smear of the lesion reveals numerous eosinophils. No organisms are seen on Gram stain. These findings may be accompanied by peripheral blood eosinophilia of up to 20%. The lesions fade and disappear within 5–7 days. Transient neonatal pustular melanosis is a pustular eruption in newborns of African-American descent. The pustules rupture leaving a collarette of scale surrounding a macular hyperpigmentation. Unlike erythema toxicum, the pustules contain mostly neutrophils and often involve the palms and soles.

7. Sucking Blisters

Bullae, either intact or as erosions (representing the blister base) without inflammatory borders, may occur over the forearms, wrists, thumbs, or upper lip. These presumably result from vigorous sucking in utero. They resolve without complications.

8. Miliaria

Obstruction of the eccrine sweat ducts occurs often in neonates and produces one of two clinical scenarios. Superficial obstruction in the stratum corneum causes miliaria crystallina, characterized by tiny (1- to 2-mm), superficial grouped vesicles without erythema over intertriginous areas and adjacent skin (eg, neck, upper chest). More commonly, obstruction of the eccrine duct deeper in the epidermis results in erythematous grouped papules in the same areas and is called miliaria rubra. Rarely, these may progress to pustules. Heat and high humidity predispose the patient to eccrine duct pore closure. Removal to a cooler environment is the treatment of choice.

9. Subcutaneous Fat Necrosis

This entity presents in the first 7 days of life as reddish or purple, sharply circumscribed, firm nodules occurring over the cheeks, buttocks, arms, and thighs. Cold injury is thought to play an important role. These lesions resolve spontaneously over a period of weeks, although in some instances they may calcify. Affected infants should be screened for hypercalcemia.

Blume-Peytavi U et al: Skin care practices for newborns and infants: review of the clinical evidence for best practices. Pediatr Dermatol 2012 Jan–Feb;29(1):1–14 [PMID: 22011065].

PIGMENT CELL BIRTHMARKS, NEVI, & MELANOMA

Birthmarks may involve an overgrowth of one or more of any of the normal components of skin (eg, pigment cells, blood vessels, lymph vessels). A nevus is a hamartoma of highly differentiated cells that retain their normal function.

1. Mongolian Spot

A blue-black macule found over the lumbosacral area in 90% of infants of Native-American, African-American, and Asian descent is called a mongolian spot. These spots are occasionally noted over the shoulders and back and may extend over the buttocks. Histologically, they consist of spindle-shaped pigment cells located deep in the dermis. The lesions fade somewhat with time as a result of darkening of the overlying skin, but some traces may persist into adult life.

2. Café au Lait Macule

A café au lait macule is a light brown, oval macule (dark brown on brown or black skin) that may be found anywhere on the body. Café au lait spots over 1.5 cm in greatest diameter are found in 10% of white and 22% of black children. These lesions persist throughout life and may increase in number with age. The presence of six or more such lesions over 1.5 cm in greatest diameter is a major diagnostic criterion for neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF-1). Patients with McCune-Albright syndrome (see Chapter 34) have a large, unilateral café au lait macule.

3. Spitz Nevus

A Spitz nevus presents as a reddish-brown smooth solitary papule appearing on the face or extremities. Histologically, it consists of epithelioid and spindle shaped nevomelanocytes that may demonstrate nuclear pleomorphism. Although these lesions can look concerning histologically, they follow a benign clinical course in most cases.

MELANOCYTIC NEVI

1. Common Moles

Well-demarcated, brown to brown-black macules represent junctional nevi. They can appear in the first years of life and increase with age. Histologically, single and nested melanocytes are present at the junction of the epidermis and dermis. Approximately 20% may progress to compound nevi—papular lesions with melanocytes both in junctional and intradermal locations. Intradermal nevi are often lighter in color and can be fleshy and pedunculated. Melanocytes in these lesions are located purely within the dermis. Nevi look dark blue (blue nevi) when they contain more deeply situated spindle-shaped melanocytes in the dermis.

2. Melanoma

Melanoma in prepubertal children is very rare. Pigmented lesions with variegated colors (red, white, blue), notched borders, asymmetrical shape, and very irregular or ulcerated surfaces should prompt suspicion of melanoma. Ulceration and bleeding are advanced signs of melanoma. If melanoma is suspected, wide local excision and pathologic examination should be performed.

3. Congenital Melanocytic Nevi

One in 100 infants is born with a congenital nevus. Congenital nevi tend to be larger and darker brown than acquired nevi and may have many terminal hairs. If the pigmented plaque covers more than 5% of the body surface area, it is considered a giant or large congenital nevus; these large nevi occur in 1 in 20,000 infants. Other classification systems characterize lesions over 20 cm as large. Often the lesions are so large they cover the entire trunk (bathing trunk nevi). Histologically, they are compound nevi with melanocytes often tracking around hair follicles and other adnexal structures deep in the dermis. The risk of malignant melanoma in small congenital nevi is controversial in the literature, but most likely very low, and similar to that of acquired nevi. Transformation to malignant melanoma in giant congenital nevi has been estimated between 1% and 5%. Of note, these melanomas often develop early in life (before puberty) and in a dermal location. Two-thirds of melanomas in children with giant congenital nevi develop in areas other than the skin.

Ibrahimi OA, Alikhan A, Eisen DB: Congenital melanocytic nevi: where are we now? J Am Acad Dermatol 2012 Oct;67(4):515.

LaVigne EA et al: Clinical and dermoscopic changes in common melanocytic nevi in school children: the Framingham school nevus study. Dermatology 2005;211:234 [PMID: 16205068].

Vourc’h-Jourdain M, Martin L, Barbarot S: Large congenital melanocytic nevi: therapeutic management and melanoma risk: a systemic review. J Am Acad Dermatol 2013 Mar;68(3):493-8.

VASCULAR BIRTHMARKS

1. Capillary Malformations

Clinical Findings

Clinical Findings

Capillary malformations are an excess of capillaries in localized areas of skin. The degree of excess is variable. The color of these lesions ranges from light red-pink to dark red.

Nevus simplex are the light red macules found over the nape of the neck, upper eyelids, and glabella of newborns. Fifty percent of infants have such lesions over their necks. Eyelid and glabellar lesions usually fade completely within the first year of life. Lesions that occupy the total central forehead area usually do not fade. Those on the neck persist into adult life.

Port-wine stains are dark red macules appearing anywhere on the body. A bilateral facial port-wine stain or one covering the entire half of the face may be a clue to Sturge-Weber syndrome, which is characterized by seizures, mental retardation, glaucoma, and hemiplegia (see Chapter 25). Most infants with smaller, unilateral facial port-wine stains do not have Sturge-Weber syndrome. Similarly, a port-wine stain over an extremity may be associated with hypertrophy of the soft tissue and bone of that extremity (Klippel-Trénaunay syndrome).

Treatment

Treatment

The pulsed dye laser is the treatment of choice for infants and children with port-wine stains.

Richter GT, Friedman AB: Hemangiomas and vascular malformations: current theory and management. Int J Pediatr. 2012.

2. Hemangioma

Clinical Findings

Clinical Findings

A red, rubbery vascular plaque or nodule with a characteristic growth pattern is a hemangioma. The lesion is often not present at birth but is represented by a permanent blanched area on the skin that is supplanted at age 2–4 weeks by red papules. Hemangiomas then undergo a rapid growth or “proliferative” phase, where growth of the lesion is out of proportion to growth of the child. At 9–12 months, growth stabilizes, and the lesion slowly involutes over the next several years. Histologically, hemangiomas are benign tumors of capillary endothelial cells. They may be superficial, deep, or mixed. The terms strawberry and cavernous are misleading and should not be used. The biologic behavior of a hemangioma is the same despite its location. Fifty percent reach maximal regression by age 5 years, 70% by age 7 years, and 90% by age 9 years, leaving redundant skin, hypopigmentation, and telangiectasia. Local complications include superficial ulceration and secondary pyoderma. Rare complications include obstruction of vital structures such as the orbit or airway.

Treatment

Treatment

Complications that require immediate treatment are (1) visual obstruction (with resulting amblyopia), (2) airway obstruction (hemangiomas of the head and neck [“beard hemangiomas”] may be associated with subglottic hemangiomas), and (3) cardiac decompensation (high-output failure). Historically, the preferred treatment for complicated hemangiomas has been prednisolone, 2–3 mg/kg orally daily for 6–12 weeks. Currently, oral propranolol (2 mg/kg/d divided BID) has replaced systemic steroids as the treatment of choice at most institutions. Reported side effects are sleep disturbance, hypoglycemia, and bradycardia. Recommendations on pretreatment cardiac evaluation vary between institutions. Interferon α2a has also been used to treat serious hemangiomas. However, 10% of patients with hemangiomas treated with interferon α2a have developed spastic diplegia, and its use is very limited. If the lesion is ulcerated or bleeding, pulsed dye laser treatment is indicated to initiate ulcer healing and immediately control pain. The Kasabach-Merritt syndrome, characterized by platelet trapping with consumption coagulopathy, does not occur with solitary cutaneous hemangiomas. It is seen only with internal hemangiomas or the rare vascular tumors such as kaposiform hemangioendotheliomas and tufted angiomas.

Bagazgoitia L et al: Propranolol for infantile hemangiomas. Pediatr Dermatol 2011 Mar–Apr;28(2):108–114.

3. Lymphatic Malformations

Lymphatic malformations may be superficial or deep. Superficial lymphatic malformations present as fluid-filled vesicles often described as resembling “frog spawn.” Deep lymphatic malformations are rubbery, skin-colored nodules occurring most commonly in the head and neck. They often result in grotesque enlargement of soft tissues. Histologically, they can be either macrocystic or microcystic.

Treatment

Treatment

Therapy includes sclerotherapy with injection of picibanil, or doxycycline, radiotherapy, or surgical excision.

EPIDERMAL BIRTHMARKS

1. Epidermal Nevus

Clinical Findings

Clinical Findings

The majority of these birthmarks present in the first year of life. They are hamartomas of the epidermis that are warty to papillomatous plaques, often in a linear array. They range in color from skin-colored to dirty yellow to brown. Histologically they show a thickened epidermis with hyperkeratosis. The condition of widespread epidermal nevi associated with other developmental anomalies (central nervous system, eye, and skeletal) is called the epidermal nevus syndrome.

Treatment

Treatment

Treatment once or twice daily with topical calcipotriene may flatten some lesions. The only definitive cure is surgical excision.

2. Nevus Sebaceus

Clinical Findings

Clinical Findings

This is a hamartoma of sebaceous glands and underlying apocrine glands that is diagnosed by the appearance at birth of a yellowish, hairless plaque in the scalp or on the face. The lesions can be contiguous with an epidermal nevus on the face, and widespread lesions can constitute part of the epidermal nevus syndrome.

Histologically, nevus sebaceus represents an overabundance of sebaceous glands without hair follicles. At puberty, with androgenic stimulation, the sebaceous cells in the nevus divide, expand their cellular volume, and synthesize sebum, resulting in a warty mass.

Treatment

Treatment

Because it has been estimated that approximately 15% of these lesions will develop secondary epithelial tumors, including basal cell carcinomas (BCC), trichoblastomas, and other benign tumors, surgical excision at puberty is recommended by most experts. The majority of the tumors develop in adulthood, although BCCs have been reported in childhood and adolescence.

CONNECTIVE TISSUE BIRTHMARKS (JUVENILE ELASTOMA, COLLAGENOMA)

Clinical Findings

Clinical Findings

Connective tissue nevi are smooth, skin-colored papules 1–10 mm in diameter that are grouped on the trunk. A solitary, larger (5–10 cm) nodule is called a shagreen patch and is histologically indistinguishable from other connective tissue nevi that show thickened, abundant collagen bundles with or without associated increases of elastic tissue. Although the shagreen patch is a cutaneous clue to tuberous sclerosis (see Chapter 25), the other connective tissue nevi occur as isolated events.

Treatment

Treatment

These nevi remain throughout life and need no treatment.

HEREDITARY SKIN DISORDERS

1. Ichthyosis

Ichthyosis is a term applied to several diseases characterized by the presence of excessive scales on the skin. These disorders represent a large and heterogeneous group of genetic and acquired defects of cornification of the skin. Classification of these diseases is clinically based, although the underlying genetic causes and pathophysiologic mechanisms responsible continue to be elucidated.

Disorders of keratinization are characterized as syndromic when the phenotype is expressed in the skin and other organs, or nonsyndromic when only the skin is affected. Ichthyoses may be inherited or acquired. Inherited disorders are identified by their underlying gene defect if known. Acquired ichthyosis may be associated with malignancy and medications, or a variety of autoimmune, inflammatory, nutritional, metabolic, infectious, and neurologic diseases. These disorders are diagnosed by clinical examination, with supportive findings on skin biopsy (including electron microscopy) and mutation analysis if available.

Treatment

Treatment

Treatment consists of controlling scaling with ammonium lactate (Lac-Hydrin or AmLactin) 12% or urea cream 10%–40% applied once or twice daily. Daily lubrication and a good dry skin care regimen are essential.

Oji V et al: Revised nomenclature and classification of inherited ichthyoses: results of the First Ichthyosis Consensus Conference in Sorèze 2009. J Am Acad Dermatol 2010 Oct;63(4):607–641.

2. Epidermolysis Bullosa

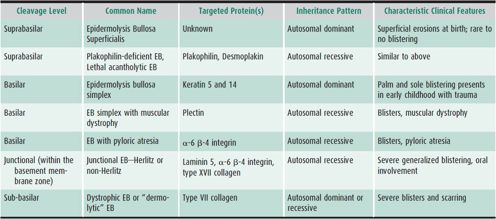

This is a group of heritable disorders characterized by skin fragility with blistering. Four major subtypes are recognized, based on the ultrastructural level of skin cleavage (Table 15–4).

Table 15–4. Major epidermolysis bullosa subtypes.

For the severely affected, much of the surface area of the skin may have blisters and erosions, requiring daily wound care and dressings. These children are prone to frequent skin infections, anemia, growth problems, mouth erosions and esophageal strictures, and chronic pain issues. They are also at increased risk of squamous cell carcinoma, a common cause of death in affected patients.

Treatment

Treatment

Treatment consists of protection of the skin with topical emollients as well as nonstick dressings. The other medical needs and potential complications of the severe forms of epidermolysis bullosa require a multidisciplinary approach. For the less severe types, protecting areas of greatest trauma with padding and dressings as well as intermittent topical or oral antibiotics for superinfection are appropriate treatments. If hands and feet are involved, reducing skin friction with 5% glutaraldehyde every 3 days is helpful.

Fine JD et al: The classification of inherited epidermolysis bullosa (EB): report of the Third International Consensus Meeting on Diagnosis and Classification of EB. J Am Acad Dermatol 2008 Jun;58(6):931–950 [Epub 2008 Apr 18].

COMMON SKIN DISEASES IN INFANTS, CHILDREN, & ADOLESCENTS

ACNE

Acne affects 85% of adolescents. The onset of adolescent acne is between ages 7 and 10 years in 40% of children. The early lesions are usually limited to the face and are primarily closed comedones.

Pathogenesis

Pathogenesis

The primary event in acne formation is obstruction of the sebaceous follicle and subsequent formation of the microcomedo (not evident clinically). This is the precursor to all future acne lesions. This phenomenon is androgen-dependent in adolescent acne. The four primary factors in the pathogenesis of acne are (1) plugging of the sebaceus follicle; (2) increased sebum production; (3) proliferation of Propionibacterium acnes in the obstructed follicle, and (4) inflammation. Many of these factors are influenced by androgens.

Drug-induced acne should be suspected in teenagers if all lesions are in the same stage at the same time and if involvement extends to the lower abdomen, lower back, arms, and legs. Drugs responsible for acne include corticotropin (ACTH), glucocorticoids, androgens, hydantoins, and isoniazid, each of which increases plasma testosterone.

Clinical Findings

Clinical Findings

Open comedones are the predominant clinical lesion in early adolescent acne. The black color is caused by oxidized melanin within the stratum corneum cellular plug. Open comedones do not progress to inflammatory lesions. Closed comedones, or whiteheads, are caused by obstruction just beneath the follicular opening in the neck of the sebaceous follicle, which produces a cystic swelling of the follicular duct directly beneath the epidermis. Most authorities believe that closed comedones are precursors of inflammatory acne lesions (red papules, pustules, nodules, and cysts). In typical adolescent acne, several different types of lesions are present simultaneously. Severe, chronic, inflammatory lesions may rarely occur as interconnecting, draining sinus tracts. Adolescents with cystic acne require prompt medical attention, because ruptured cysts and sinus tracts result in severe scar formation.

Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

Consider rosacea, nevus comedonicus, flat warts, miliaria, molluscum contagiosum, and the angiofibromas of tuberous sclerosis.

Treatment

Treatment

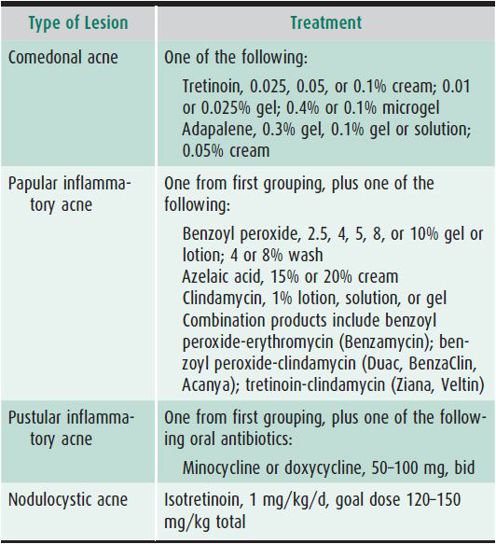

Different treatment options are listed in Table 15–5. Recent data have indicated that combination therapy that targets multiple pathogenic factors increases the efficacy of treatment and rate of improvement.

Table 15–5. Acne treatment.

A. Topical Keratolytic Agents

Topical keratolytic agents address the plugging of the follicular opening with keratinocytes and include retinoids, benzoyl peroxide, and azelaic acid. The first-line treatment for both comedonal and inflammatory acne is a topical retinoid (tretinoin [retinoic acid], adapalene, and tazarotene). These are the most effective keratolytic agents and have been shown to prevent the microcomedone. These topical agents may be used once daily, or the combination of a retinoid applied to acne-bearing areas of the skin in the evening and a benzoyl peroxide gel or azelaic acid applied in the morning may be used. This regimen will control 80%–85% of cases of adolescent acne.

B. Topical Antibiotics

Topical antibiotics are less effective than systemic antibiotics and at best are equivalent in potency to 250 mg of tetracycline orally once a day. One percent clindamycin phosphate solution is the most efficacious topical antibiotic. Most P acnes strains are now resistant to topical erythromycin solutions. Topical antibiotic therapy alone should never be used. Multiple studies have shown a combination of benzoyl peroxide or a retinoid and a topical antibiotic are more effective than the antibiotic alone. Benzoyl peroxide has been shown to help minimize the development of bacterial resistance at sites of application. The duration of application of topical antimicrobials should be limited unless benzoyl peroxide is used. Several combination products (benzoyl peroxide and clindamycin, tretinoin and clindamycin, adapalene and benzoyl peroxide) are available which may simplify the treatment regimen and increase patient compliance.

C. Systemic Antibiotics

Antibiotics that are concentrated in sebum, such as tetracycline, minocycline, and doxycycline, should be reserved for moderate to severe inflammatory acne. The usual dose of tetracycline is 0.5–1.0 g divided twice a day on an empty stomach; minocycline and doxycycline 50–100 mg taken once or twice daily can be taken with food. Monotherapy with oral antibiotics should never be used. Recent recommendations are that oral antibiotics should be used for a finite time period, and then discontinued as soon as there is improvement in the inflammatory lesions. The tetracycline antibiotics should not be given to children younger than 8 years of age due to the effect on dentition (staining of teeth). Doxycycline may induce significant photosensitivity, and minocycline can cause bluish-gray dyspigmentation of the skin, vertigo, headaches, and drug-induced lupus. These antibiotics have anti-inflammatory effects in addition to decreasing P acnes in the follicle.

D. Oral Retinoids

An oral retinoid, 13-cis-retinoic acid (isotretinoin; Accutane), is the most effective treatment for severe cystic acne. The precise mechanism of its action is unknown, but apoptosis of sebocytes, decreased sebaceous gland size, decreased sebum production, decreased follicular obstruction, decreased skin bacteria, and general anti-inflammatory activities have been described. The initial dosage is 0.5–1 mg/kg/d. This therapy is reserved for severe nodulocystic acne, or acne recalcitrant to aggressive standard therapy. Side effects include dryness and scaling of the skin, dry lips, and, occasionally, dry eyes and dry nose. Fifteen percent of patients may experience some mild achiness with athletic activities. Up to 10% of patients experience mild, reversible hair loss. Elevated liver enzymes and blood lipids have rarely been described. Acute depression may occur. Isotretinoin is teratogenic in young women of childbearing age. Because of this and the other side effects, it is not recommended unless strict adherence to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) guidelines is ensured. The FDA has implemented a strict registration program (iPLEDGE) that must be used to obtain isotretinoin.

E. Other Acne Treatments

Hormonal therapy (oral contraceptives) is often an effective option for girls who have perimenstrual flares of acne or have not responded adequately to conventional therapy. Adolescents with endocrine disorders such as polycystic ovary syndrome also see improvement of their acne with hormonal therapy. Oral contraceptives can be added to a conventional therapeutic regimen and should always be used in female patients who are prescribed oral isotretinoin unless absolute contraindications exist. There is growing data regarding the use of light, laser, and photodynamic therapy in acne. However, existing studies are of variable quality, and although there is evidence to suggest that these therapies offer benefit in acne, the evidence is not sufficient to recommend any device as monotherapy in acne.

F. Patient Education and Follow-Up Visits

The multifactorial pathogenesis of acne and its role in the treatment plan must be explained to adolescent patients. Good general skin care includes washing the face consistently and using only oil-free, noncomedogenic cosmetics, face creams, and hair sprays. Acne therapy takes 8–12 weeks to produce improvement, and this delay must be stressed to the patient. Realistic expectations should be encouraged in the adolescent patient because no therapy will eradicate all future acne lesions. A written education sheet is useful. Follow-up visits should be made every 12–16 weeks. An objective method to chart improvement should be documented by the provider, because patients’ assessment of improvement tends to be inaccurate.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree