Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States 2011. MMWR Surveill Summ 2012;61(SS–4) [PMID: 22673000].

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Sexual identity, sex of sexual contacts and health-risk behaviors among students in grades 9–12—youth risk behavior surveillance, selected sites, United States, 2001–2009. MMWR Surveill Summ 2011; 60 [PMID: 21659985].

Lindberg LD, Jones R, Santelli JS: Noncoital sexual activities among adolescents. J Adolesc Health 2008;43:231 [PMID: 18710677].

Shafii T, Burstein G: The adolescent sexual health visit. Obstet Gynecol Clin N Am 2009;36:99 [PMID: 19344850].

State Policies in Brief: Minor’s access to STI services as of March 1, 2013. Guttmacher Organization web site. Available at: http://www.guttmacher.org/statecenter/spibs/spib_MASS.pdf. Accessed March 26, 2013.

RISK FACTORS

Certain behaviors and experiences put the adolescent at higher risk for developing STIs. These include early age at sexual debut, lack of condom use, multiple partners, prior STI, history of STI in a partner, and sex with a partner who is 3 or more years older. The type of sex affects risk as well, with intercourse being riskier than oral sex. Other risk-taking behaviors associated with STIs in adolescents are smoking, alcohol use, drug use, dropping out of school, pregnancy, and depression.

The adolescent female is especially predisposed to chlamydia, gonorrhea, and HPV infection because the cervix during adolescence has an exposed squamocolumnar junction. The rapidly dividing cells in this area are especially susceptible to microorganism attachment and infection. During early to midpuberty, this junction slowly invaginates as the uterus and cervix mature, and by the late teens to early 20s the squamocolumnar junction is inside the cervix.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States 2011. MMWR Surveill Summ 2012;61(SS–4) [PMID: 22673000].

Halpern-Flesher BL et al: Oral versus vaginal sex among adolescents: perceptions, attitudes, and behavior. Pediatrics 2005;115:845 [PMID: 15805354].

Swartzendruber A et al: It takes 2: partner attributes associated with sexually transmitted infections among adolescents. Sex Trans Dis 2013;40:372 [PMID: 23588126].

PREVENTION OF SEXUALLY TRANSMITTED INFECTIONS

Efforts to reduce STI risk behavior should begin before the onset of sexual experimentation: first by helping youth personalize their risk for STIs and encouraging positive behaviors that minimize these risks, and then by enhancing communication skills with sexual partners about STI prevention, abstinence, and condom use.

Primary prevention focuses largely on education and risk-reduction techniques. It is essential to recognize that a key task of adolescence is developing a sexual identity. Teenagers are sexual beings that will decide if, when, and how they are going to initiate sexual involvement. Healthcare providers should routinely address sexuality as part of well-adolescent checkups. Being open and frank about the risks and benefits of each specific type of sexual activity will help youth think about their decision and the consequences. Although more than 90% of students have been taught about HIV infection and other STIs in school, adolescents still have a difficult time personalizing risk. Discussing prevalence, symptoms, and sequelae of STIs can raise awareness and help teenagers make informed decisions about initiating sexual activity and the use of safer sex techniques. Abstinence is theoretically an effective method of preventing sexually transmitted infections. However, many studies have failed to show sustainable protection. Making condoms available reiterates the message that safer sex is vital to health. Discussing condoms, dental dams, and the proper use of lubrication also facilitates safer sex practices. Condoms may prevent infections with HIV, HPV, gonorrhea, Chlamydia, and herpes simplex virus (HSV). They are probably effective in preventing other STIs as well.

Secondary prevention requires identifying and treating STIs (see the next section on Screening for Sexually Transmitted Infections) before infected individuals transmit infection to others. Access to confidential medical care is critical to this objective. Identifying and treating STIs in partners is essential in limiting the spread of these infections. Cooperation with the state or county health department is valuable, because these agencies assume the responsibility for locating the contacts of infected persons and ensuring appropriate treatment.

Tertiary prevention is directed toward complications of a specific illness. Examples of tertiary prevention would be treating pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) before infertility develops, following the serologic response to syphilis to prevent late-stage syphilis, treating cervicitis to prevent PID, or treating a chlamydial infection before epididymitis ensues.

Finally, preexposure vaccination against hepatitis B, hepatitis A, and HPV reduces the risk for these preventable STIs. All adolescents should have prior or current immunization against hepatitis B (see Chapter 10). However, because hepatitis B infection is frequently sexually transmitted, this vaccine is especially critical for all unvaccinated patients being evaluated for an STI. Hepatitis A vaccination is recommended for all individuals. Preexposure vaccination for HPV will decrease the risk for cervical dysplasia and cervical cancer in females, and decreases the risk for genital warts and both anal and oropharyngeal cancer in males and females, which can occur decades later (see Chapter 10).

Delisi K, Gold MA: The initial adolescent preventive care visit. Clin Obstet Gyn 2008;51:190 [PMID: 18463451].

Rietmeijer CA: Risk reduction counseling for prevention of sexually transmitted infections: how it works and how to make it work. Sex Transm Infect 2007;83:2 [PMID: 17283359].

Shafii T, Burstein GR: The adolescent sexual health visit. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am 2009;36:99 [PMID: 19344850].

SCREENING FOR SEXUALLY TRANSMITTED INFECTIONS

The ability of the healthcare provider to obtain an accurate sexual history is crucial in prevention and control efforts. Teenagers should be asked open-ended questions about their sexual experiences to assess their risk for STIs. Questions must be clear to the youth, so choose language that the adolescent will understand. If the adolescent has ever engaged in sexual activity, the provider needs to determine what kind of sexual activity (mutual masturbation or oral, anal, or vaginal sex); whether it has been opposite-sex, same-sex, or both; whether birth control and condoms were used; and whether it has been consensual or forced. During the interview, the clinician should take the opportunity to discuss risk-reduction techniques regardless of the history obtained from the youth.

A routine laboratory screening process is warranted if the patient has engaged in intercourse, presents with STI symptoms, or reports a partner with an STI. The availability of nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs), primarily for Chlamydia and Neisseria gonorrhoeae, has changed the nature of STI screening and intervention. These amplification tests are more than 95% sensitive and more than 99% specific, using either urine or cervical/urethral or vaginal swabs. Annual screening of all sexually active females aged 25 years or younger is recommended for Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Routine chlamydial testing should be considered for all adolescent males, especially for males who have sex with men, have new or multiple sex partners, or are in correctional facilities. For men who have sex with men, consideration should be given to testing oropharyngeal and rectal sites, as asymptomatic infections are common. Use of NAAT is recommended for samples from these sites, but such tests are not currently FDA-approved and providers must locate a laboratory that has performed the necessary validation studies.

Initial screening for urethritis in males begins with a physical examination. A first-catch urine sample (the first 10–40 mL of voided urine collected after not voiding for 2 hours) should be sent for Chlamydia and N gonorrhoeae testing if there are no signs (urethral discharge or lesions) or symptoms. With signs or symptoms of urethritis, a urethral swab should be sent to test for both N gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia. A wet mount preparation should then be done on a spun urine sample or from urethral discharge, evaluating for the presence of Trichomonas vaginalis. Newer technologies, such as enzyme-linked immunoassays (EIA) and NAAT testing, have become available that allow greater sensitivity and specificity in making the diagnosis of T vaginalis in males and females.

Screening asymptomatic females is more complicated because a variety of approaches are available. Generally, either a first-void urine specimen, a cervical swab, or a vaginal swab is used to screen for Chlamydia and N gonorrhoeae by NAAT. Any vaginal discharge symptoms should include evaluation of wet mount of vaginal secretions to check for bacterial vaginosis and trichomoniasis, and a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation to screen for yeast infections. The Papanicolaou (Pap) smear serves to evaluate the cervix for the presence of dysplasia. The first Pap smear should be performed at age 21 years and then every 3 years. HPV typing is not recommended.

In urban areas with a relatively high rate of syphilis and in males who have sex with men, a screening test should be drawn yearly or more frequently if higher risk encounters are more frequent. RPR and HIV antibody tests should be done in all individuals in whom a concomitant STI is present.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Sexually transmitted diseases guidelines, 2010. MMWR 2010;59(RR-12):10–11 [PMID: 21160459].

Henry-Reid LM et al: Current pediatrician practices in identifying high-risk behaviors of adolescents. Pediatrics 2010;125:e741 [PMID: 20308220].

Kent CK et al: Prevalence of rectal, urethral, and pharyngeal Chlamydia and gonorrhea detected in 2 clinical settings among men who have sex with men: San Francisco, California, 2003. Clin Infect Dis 2005;41:67 [PMID: 15937765].

SIGNS & SYMPTOMS

The most common symptoms in males are dysuria and penile discharge resulting from urethral inflammation. However, providers should be aware that many urethral infections are asymptomatic. Less common symptoms are scrotal pain, hematuria, proctitis, and pruritus in the pubic region. Signs include epididymitis, orchitis, and urethral discharge. Rarely do males develop systemic symptoms. However, especially for MSM, but for any sexually active adolescent at risk for HIV infection who presents with nonspecific viral symptoms, acute HIV seroconversion illness should be considered in the differential diagnoses. For females, the most common symptoms are vaginal discharge and dysuria. Again, infection may be asymptomatic. Vaginal itching and irregular menses or spotting are also common. Abdominal pain, fever, and vomiting, although less common and specific, are signs of PID. Pain in the genital region and dyspareunia may be present.

Signs that can be found in both males and females with an STI include genital ulcerations, adenopathy, and genital warts.

THE MOST COMMON ANTIBIOTIC-RESPONSIVE SEXUALLY TRANSMITTED INFECTIONS

C trachomatis and N gonorrhoeae are STIs that are epidemic in the United States and are readily treated when appropriate antibiotics are administered in a timely fashion.

CHLAMYDIA TRACHOMATIS INFECTION

General Considerations

General Considerations

C trachomatis is the most common bacterial cause of STIs in the United States. In 2011, over 1.4 million cases in adolescents and young adults were reported to the CDC. C trachomatis is an obligate intracellular bacterium that replicates within the cytoplasm of host cells. Destruction of Chlamydia-infected cells is mediated by host immune responses.

Clinical Findings

Clinical Findings

A. Symptoms and Signs

Clinical infection in females manifests as dysuria, urethritis, vaginal discharge, cervicitis, irregular vaginal bleeding, or PID. The presence of mucopus at the cervical os (mucopurulent cervicitis) is a sign of chlamydial infection or gonorrhea. Chlamydial infection is asymptomatic in 75% of females.

Chlamydial infection may be asymptomatic in 70% of males or manifest as dysuria, urethritis, or epididymitis. Some patients complain of urethral discharge. On clinical examination, a clear white discharge may be found after milking the penis. Proctitis or proctocolitis from Chlamydia may occur in adolescents practicing receptive anal intercourse.

B. Laboratory Findings

NAAT is the most sensitive (92%–99%) way to detect Chlamydia. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) or direct fluorescent antibody (DFA) tests are less sensitive, but may be the only testing option in some centers.

A cervical or vaginal swab, using the manufacturer’s swab provided with the specific test, or first-void urine specimen, should be obtained. For urine screening, yields of testing are maximized when collecting between 10 and 20 mL of urine and ensuring that patient has not voided for 2 hours. Often a single swab can be used to collect both the Chlamydia and N gonorrhoeae specimen. To optimize detection of Chlamydia from the cervix, columnar cells need to be collected by inserting the swab in the os and rotating it 360 degrees. NAAT is not licensed for rectal samples but some laboratories have validated testing on rectal specimens for C trachomatis. Thus, when a rectal specimen is obtained, this must often be evaluated by less sensitive culture methods unless there is access to a laboratory that has validated Chlamydia NAAT for nongenital sites.

The first-void urine test for leukocyte esterase was previously used for screening asymptomatic, sexually active males. Because of the high false-positive rate, this screening technique is not commonly used. In symptomatic males, examination of the urine sediment for white blood cells (WBCs) provides a screen for urethritis, although it is often impractical to perform in a clinical setting.

In general, a first-void urine sample, or urethral swab for NAAT, should be obtained at least annually. Some studies suggest that more frequent screenings—every 6 months—in higher-prevalence populations can decrease the rate of chlamydial infection. For both males and females, testing urine allows for more frequent screening and simplifies screening in large group settings, such as schools and correctional facilities.

Complications

Complications

Epididymitis is a complication in males. Reiter syndrome occurs in association with chlamydial urethritis. This should be suspected in male patients who are sexually active and present with low back pain (sacroiliitis), arthritis (polyarticular), characteristic mucocutaneous lesions, and conjunctivitis. PID is an important complication in females.

Treatment

Treatment

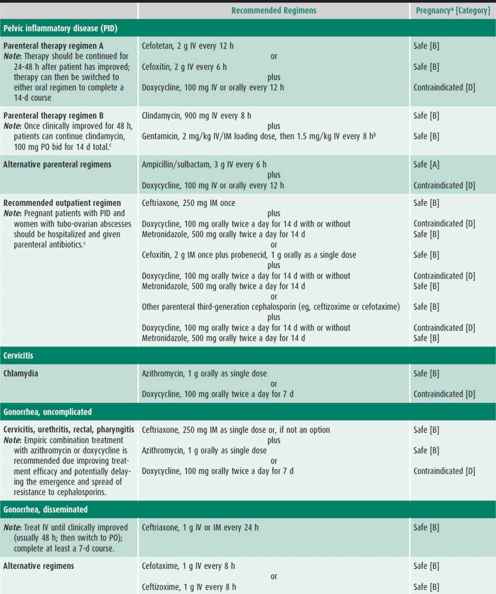

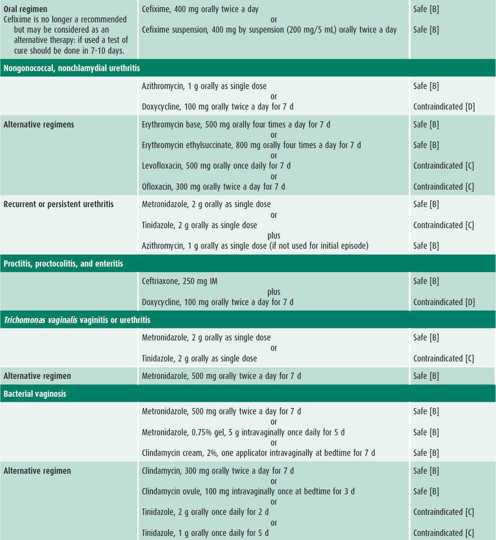

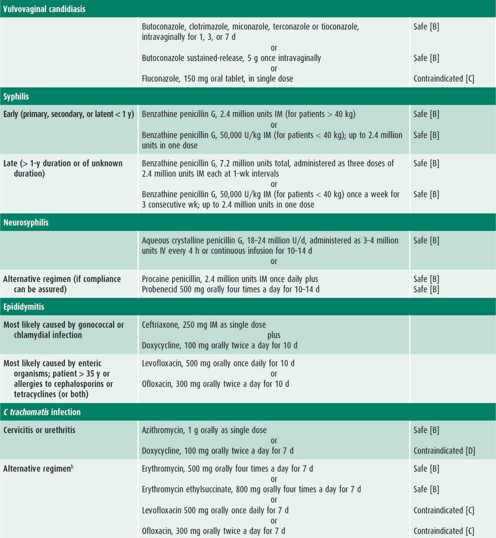

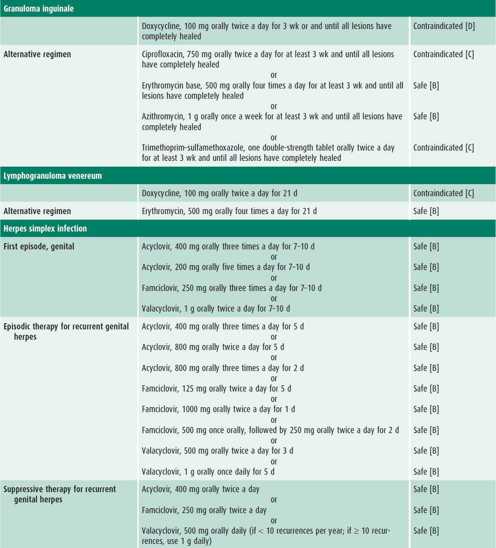

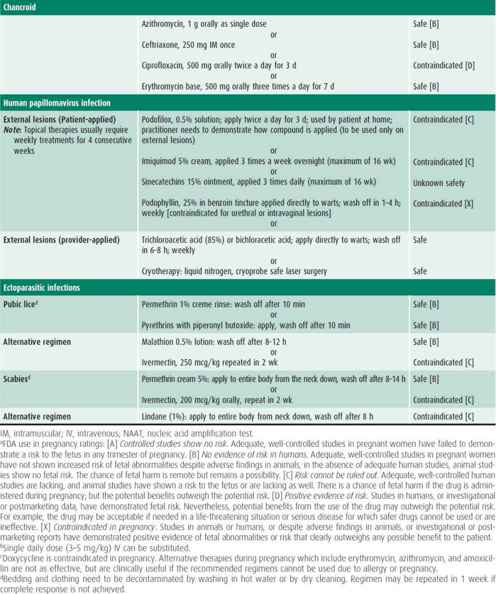

Infected patients and their contacts, regardless of the extent of signs or symptoms, need to receive treatment (Table 44–1). Reinfection caused by failure of contacts to receive treatment or the initiation of sexual activity with a new infected partner puts the adolescent at high risk of acquiring a repeat chlamydial infection within several months of the first infection. Because of this increased risk, all infected females and males should be retested approximately 3 months after treatment.

Baraitser P, Alexander S, Sheringham J: Chlamydia trachomatis screening in young women. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2011;23:315 [PMID: 21897235].

Bebear C, de Barbeyrac B: Genital Chlamydia trachomatis infections. Clin Micro Infect 2009;15:4 [PMID: 19220334].

Geisler WM. Diagnosis and management of uncomplicated Chlamydia trachomatis infections in adolescents and adults: summary of evidence reviewed for the 2010 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention sexually transmitted guidelines. Clin Infect Dis 2011;53:S92 [PMID: 22080274].

NEISSERIA GONORRHOEAE INFECTION

General Considerations

General Considerations

Gonorrhea is the second most prevalent bacterial STI in the United States, where an estimated 700,000 new N gonorrhoeae infections occur each year. While the overall rates have decreased, gonorrhea rates continue to be highest among adolescents and young adults. Among females in 2011, 15- to 19-year-olds and 20- to 24-year-olds had the highest rates of gonorrhea; among males, 20- to 24-year-olds had the highest rate.

Sites of infection include the cervix, urethra, rectum, and pharynx. In addition, gonorrhea is a cause of PID. Humans are the natural reservoir. Gonococci are present in the exudate and secretions of infected mucous membranes.

Clinical Findings

Clinical Findings

A. Symptoms and Signs

In uncomplicated gonococcal cervicitis, females are symptomatic 23%–57% of the time, presenting with vaginal discharge and dysuria. Urethritis and pyuria may also be present. Mucopurulent cervicitis with a yellowish discharge may be found, and the cervix may be edematous and friable. Other symptoms include abnormal menstrual periods and dyspareunia. Approximately 15% of females with endocervical gonorrhea have signs of involvement of the upper genital tract. Compared with chlamydial infection, pelvic inflammation with gonorrhea has a shorter duration, but an increased intensity of symptoms, and is more often associated with fever. Symptomatic males usually have a yellowish-green urethral discharge and burning on urination, but most males (55%–67%) with N gonorrhoeae are asymptomatic. Both males and females can develop gonococcal proctitis and pharyngitis after appropriate exposure.

B. Laboratory Findings

A first void urine sample or cervical or vaginal swab from females should be sent for NAAT. Culture or NAAT for N gonorrhoeae in males can be achieved with a swab of the urethra or first-void urine. Urethral culture is less sensitive (85%) compared with the 95%–99% sensitivity using NAAT methods on either urethral or urine specimens. Gram stain of urethral discharge showing gram-negative intracellular diplococci indicates gonorrhea in a male.

If proctitis is present, appropriate cultures should be obtained and treatment for both gonorrhea and chlamydial infection given. If oral exposure to gonorrhea is suspected, cultures should be taken and the patient given empiric treatment. If there is access to a laboratory that has validated NAAT for oropharyngeal or rectal specimens, this will substantially increase detection over culture methods.

Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

Gonococcal pharyngitis needs to be differentiated from pharyngitis caused by streptococcal infection, herpes simplex, adenovirus, and infectious mononucleosis. Chlamydial infection needs to be differentiated from gonococcal infection.

Complications

Complications

Disseminated gonococcal infection occurs in a minority (0.5%–3%) of patients with untreated gonorrhea. Hematogenous spread most commonly causes arthritis and dermatitis. The joints most frequently involved are the wrist, metacarpophalangeal joints, knee, and ankle. Skin lesions are typically tender, with hemorrhagic or necrotic pustules or bullae on an erythematous base occurring on the distal extremities. Disseminated disease occurs more frequently in females than in males. Risk factors include pregnancy and gonococcal pharyngitis. Gonorrhea is complicated occasionally by perihepatitis.

Treatment (see Table 44–1)

Treatment (see Table 44–1)

In 2010, the CDC made two significant changes to gonorrhea treatment recommendations: dual treatment and treatment with ceftriaxone 250 mg IM regardless of anatomic site involved. These changes reflect increasing resistance to cephalosporins; the frequency of coinfection with Chlamydia; and the need to increase consistency of treatment regimens.

CDC guidelines also state that N gonorrhoeae and C trachomatis do not require tests of cure when they are treated with first-line medications, unless the patient remains symptomatic. If retesting is indicated, it should be delayed for 1 month after completion of therapy if NAATs are used. Retesting might also be considered for sexually active adolescents likely to be reinfected. Due to increasing resistance of N gonorrhoeae to cephalosporins, providers considering treatment failure should also obtain a gonorrhea culture to assess for antibiotic resistance. Patients should be advised to abstain from sexual intercourse until both they and their partners have completed a course of treatment. Treatment for disseminated disease may require hospitalization. Quinolones should no longer be used to treat gonorrhea due to high levels of quinolone resistance in all populations in the United States. Failure of initial treatment should prompt reevaluation of the patient and consideration of retreatment with ceftriaxone.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Sexually transmitted diseases guidelines, 2010. MMWR 2010;59(RR-12):49–55 [PMID: 21160459].

Kirkcaldy RD, Bolan GA, Wasserheit JN. Cephalosporin-resistant gonorrhea in North Amercia. JAMA 2013;309:185 [PMID: 23299612].

THE SPECTRUM OF SIGNS & SYMPTOMS OF SEXUALLY TRANSMITTED INFECTIONS

The patient presenting with an STI usually has one or more of the signs or symptoms described in this section. Management considerations for STIs include assessing the patient’s adherence to therapy and ensuring follow-up, treating STIs in partners, and determining pregnancy risk. Treatment of each STI is detailed in Table 44–1.

CERVICITIS

General Considerations

General Considerations

In most cases of cervicitis no organism is isolated. The most common causes include C trachomatis or N gonorrhoeae. HSV, T vaginalis, and Mycoplasma genitalium are less common causes. Bacterial vaginosis is now recognized as a cause of cervicitis. Cervicitis can also be present without an STI.

Clinical Findings

Clinical Findings

A. Symptoms and Signs

Two major diagnostic signs characterize cervicitis: (1) purulent or mucopurulent endocervical exudate visible in the endocervical canal or on an endocervical swab and (2) easily induced bleeding with the passage of a cotton swab through the cervical os. Cervicitis is often asymptomatic, but many patients with cervicitis have an abnormal vaginal discharge or postcoital bleeding.

B. Laboratory Findings

Although endocervical Gram stain may show an increased number of polymorphonuclear leukocytes, this finding has a low positive predictive value and is not recommended for diagnosis. Patients with cervicitis should be tested for C trachomatis, N gonorrhoeae, and trichomoniasis by using the most sensitive and specific tests available at the site.

Complications

Complications

Persistent cervicitis is difficult to manage and requires reassessment of the initial diagnosis and reevaluation for possible re-exposure to an STI. Cervicitis can persist despite repeated courses of antimicrobial therapy. Presence of a large ectropion can contribute to persistent cervicitis.

Treatment

Treatment

Empiric treatment for both gonorrhea and chlamydial infection is recommended because coinfection is common. If the patient is asymptomatic except for cervicitis, then treatment may wait until diagnostic test results are available (see Table 44–1). Follow-up is recommended if symptoms persist. Patients should be instructed to abstain from sexual intercourse until they and their sex partners are cured and treatment is completed.

Lusk MJ, Konecny P: Cervicitis: a review. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2008;21:49 [PMID: 18192786].

PELVIC INFLAMMATORY DISEASE

General Considerations

General Considerations

Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) is defined as inflammation of the upper female genital tract and may include endometritis, salpingitis, tubo-ovarian abscess, and pelvic peritonitis. It is the most common gynecologic disorder necessitating hospitalization for female patients of reproductive age in the United States. Over 1 million females develop PID annually, 60,000 are hospitalized, and over 150,000 are evaluated in outpatient settings. The incidence is highest in the teen population. Teenage girls who are sexually active have a high risk (1 in 8) of developing PID, whereas women in their 20s have one-tenth the risk. Predisposing risk factors include multiple sexual partners, younger age of initiating sexual intercourse, prior history of PID, and lack of condom use. Lack of protective antibody from previous exposure to sexually transmitted organisms and cervical ectopy contribute to the development of PID. Many adolescents with subacute or asymptomatic infection are never identified.

PID is a polymicrobial infection. Causative agents include N gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia, anaerobic bacteria that reside in the vagina, and genital mycoplasmas. Vaginal douching and other mechanical factors such as older intrauterine devices or prior gynecologic surgery increase the risk of PID by providing access of lower genital tract organisms to pelvic organs. Recent menses and bacterial vaginosis have been associated with the development of PID.

Clinical Findings

Clinical Findings

A. Symptoms and Signs

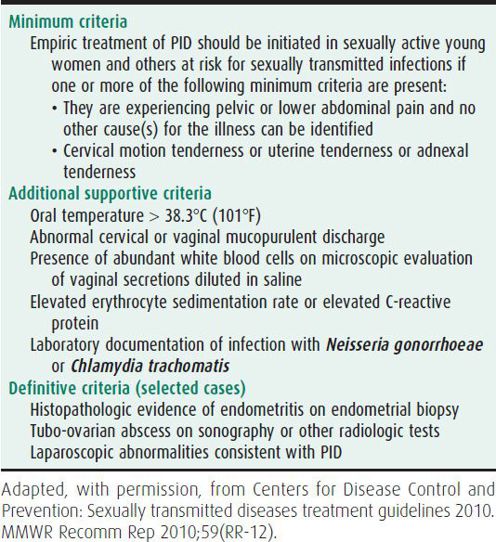

PID may be challenging to diagnose because of the wide variation in the symptoms and signs. No single historical, clinical, or laboratory finding has both high sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis. Diagnosis of PID is usually made clinically (Table 44–2). Typical patients have lower abdominal pain, pelvic pain, or dysuria. However, the patient may be febrile or have additional systemic symptoms such as nausea or vomiting. Vaginal discharge is variable. Cervical motion tenderness, uterine or adnexal tenderness, or signs of peritonitis are often present. Mucopurulent cervicitis is present in 50% of patients. Tubo-ovarian abscesses can often be detected by careful physical examination (feeling a mass or fullness in the adnexa).

B. Laboratory Findings

Laboratory findings may include elevated WBCs with a left shift and elevated acute phase reactants (erythrocyte sedimentation rate or C-reactive protein). A positive test for N gonorrhoeae or C trachomatis is supportive, although 25% of the time neither of these bacteria is detected. Pregnancy needs to be ruled out, because patients with an ectopic pregnancy can present with abdominal pain and concomitant pregnancy will affect management.

C. Diagnostic Studies

Laparoscopy is the gold standard for detecting salpingitis. It is used if the diagnosis is in question or to help differentiate PID from an ectopic pregnancy, ovarian cysts, or adnexal torsion. Endometrial biopsy should be performed in women undergoing laparoscopy who do not have visual evidence of salpingitis as some women may only have endometritis. The clinical diagnosis of PID has a positive predictive value for salpingitis of 65%–90% in comparison with laparoscopy. Pelvic ultrasonography also is helpful in detecting tubo-ovarian abscesses, which are found in almost 20% of teens with PID. Transvaginal ultrasound is more sensitive than abdominal ultrasound. All women who have acute PID should be tested for N gonorrhoeae and C trachomatis and should be screened for HIV infection.

Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnosis includes other gynecologic illnesses (ectopic pregnancy, threatened or septic abortion, adnexal torsion, ruptured and hemorrhagic ovarian cysts, dysmenorrhea, endometriosis, or mittelschmerz), gastrointestinal illnesses (appendicitis, cholecystitis, hepatitis, gastroenteritis, or inflammatory bowel disease), and genitourinary illnesses (cystitis, pyelonephritis, or urinary calculi).

Complications

Complications

Scarring of the fallopian tubes is one of the major sequelae of PID. After one episode of PID, 17% of patients become infertile, 17% develop chronic pelvic pain, and 10% will have an ectopic pregnancy. Infertility rates increase with each episode of PID; three episodes of PID result in a 73% infertility rate. Duration of symptoms appears to be the largest determinant of infertility. Hematogenous or lymphatic spread of organisms from the fallopian tubes rarely causes inflammation of the liver capsule (perihepatitis) resulting in symptoms of pleuritic right upper quadrant pain and elevation of liver function tests.

Treatment

Treatment

The objectives of treatment are both to achieve a clinical cure and to prevent long-term sequelae. There are no differences in short- and long-term clinical and microbiologic response rates between parenteral and oral therapy. PID is frequently managed at the outpatient level, although some clinicians argue that all adolescents with PID should be hospitalized because of the rate of complications. Severe systemic symptoms and toxicity, signs of peritonitis, inability to take fluids, pregnancy, nonresponse or intolerance of oral antimicrobial therapy, and tubo-ovarian abscess favor hospitalization. In addition, if the healthcare provider believes that the patient will not adhere to treatment, hospitalization is warranted. Pregnant women with PID should be admitted to hospital and treated with parental antibiotics to reduce the increased risk of morbidity. Surgical drainage may be required for adequate treatment of tubo-ovarian abscesses.

The antibiotic regimens described in Table 44–1 are broad spectrum to cover the numerous microorganisms associated with PID. All treatment regimens should be effective against N gonorrhoeae and C trachomatis because negative endocervical screening tests do not rule out upper reproductive tract infection with these organisms. Outpatient treatment should be reserved for compliant patients who have classic signs of PID without systemic symptoms. Patients with PID who receive outpatient treatment should be reexamined within 24–48 hours, with phone contact in the interim, to detect persistent disease or treatment failure. Patients should have substantial improvement within 48–72 hours. An adolescent should be reexamined 7–10 days after the completion of therapy to ensure the resolution of symptoms.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree