Background

While research has demonstrated increasing risk for severe maternal morbidity in the United States, risk at lower volume hospitals remains poorly characterized. More than half of all obstetric units in the United States perform <1000 deliveries per year and improving care at these hospitals may be critical to reducing risk nationwide.

Objective

We sought to characterize maternal risk profiles and severe maternal morbidity at low-volume hospitals in the United States.

Study Design

We used data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample to evaluate trends in severe maternal morbidity and comorbid risk during delivery hospitalizations in the United States from 1998 through 2011. Comorbid maternal risk was estimated using a comorbidity index validated for obstetric patients. Severe maternal morbidity was defined as the presence of any 1 of 15 diagnoses representative of acute organ injury and critical illness.

Results

A total of 2,300,279 deliveries occurred at hospitals with annual delivery volume <1000, representing 20% of delivery hospitalizations overall. There were 7849 cases (0.34%) of severe morbidity in low-volume hospitals and this risk increased over the course of the study from 0.25% in 1998 through 1999 to 0.49% in 2010 through 2011 ( P < .01). The risk in hospitals with ≥1000 deliveries increased from 0.35-0.62% during the same time periods. The proportion of patients with the lowest comorbidity decreased, while the proportion of patients with highest comorbidity increased the most. The risk of severe morbidity increased across all women including those with low comorbidity scores. Risk for severe morbidity associated with obstetric hemorrhage, infection, hypertensive diseases of pregnancy, and medical conditions all increased during the study period.

Conclusion

Our findings demonstrate increasing maternal risk at hospitals performing <1000 deliveries per year broadly distributed over the patient population. Rates of morbidity in centers with ≥1000 deliveries have also increased. These findings suggest that maternal safety improvements are necessary at all centers regardless of volume.

Introduction

Research has demonstrated increasing risk for severe maternal morbidity and mortality in the United States over recent decades. Severe maternal morbidity now complicates approximately 50,000 deliveries per year in the United States. These trends resulted in calls to improve maternal safety and reduce morbidity and mortality. Factors associated with the rising risk include increased rates of obesity, cesarean delivery, and medical comorbidity, and severe morbidity risk can be estimated based on patient characteristics.

Understanding trends in maternal risk and outcomes at hospitals performing <1000 deliveries per year may be critically important to improve overall maternal care quality. Hospitals with obstetric volumes of <1000 represent more than half of all centers providing obstetrical care and account for approximately one fifth of all deliveries. Delineating the risk profile of patients at these centers and understanding which associated conditions lead to severe morbidity may be important, in particular, for successful regionalization of maternal care, with referral institutions taking the lead in both managing complicated patients and providing leadership on safety strategies and quality improvement for smaller centers. Specifically, it may be important to: (i) identify whether increases in maternal risk are due to a small cohort of relatively high-risk patients, or are spread more diffusely across the population; and (ii) determine to what degree increased risk for maternal morbidity is associated with specific, leading causes of maternal mortality such as infection, hemorrhage, medical conditions, and hypertensive diseases of pregnancy. Comorbid risk can be estimated by the prevalence of both specific conditions associated with severe morbidity or summarized in a comorbidity index, specifically designed for and validated in obstetric patient populations.

Given the importance of characterizing maternal risk in hospitals performing <1000 deliveries per year, this study had 2 main purposes: (1) to characterize temporal trends in comorbid risk for delivery hospitalizations both in terms of specific diagnoses and overall comorbid risk; and (2) to characterize trends in risk for severe morbidity overall and in relation to leading causes of maternal mortality.

Materials and Methods

For this analysis we used data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The NIS is the largest publicly available, all-payer inpatient database in the United States and it contains a sample of approximately 20% of all hospitals nationally, selected to generate a sample that is representative of all US hospitalizations. Through 2011, the data feature all discharge claims in individual hospitals. The hospitals sampled in the NIS include academic, community, nonfederal, general, and specialty-specific centers across the United States. Approximately 8 million hospital stays from a total of 45 states in 2010 are included in the NIS. As this data set was entirely deidentified, exemption status was given by the institutional review board from Columbia University. This permission was obtained prior to commencement of the study.

Hospitals were dichotomized based on whether they performed <1000 or ≥1000 deliveries per year. Prior analyses have used varying obstetric volume cutoffs ; the volume categories used in this analysis were chosen because: (1) they represent easily interpretable and clinically meaningful distinctions in obstetric volume; and (2) centers performing <1000 deliveries annually account approximately for the lowest delivery volume quintile nationally. To identify hospitals, we calculated the total number of deliveries over the study period and divided this by the number of years in which a hospital had at least 1 delivery. Hospital classification was based on whether mean delivery volume was <1000 or ≥1000 per year. Deliveries were identified based on whether International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision billing codes v27.x and/or 650 were present. These codes have been shown to identify >95% of all delivery hospitalizations. This study included births from 1998 through 2011, as NIS data after 2011 do not include all discharges from individual centers. Besides hospital volume, other hospital characteristics included location (urban vs rural), teaching status (teaching vs nonteaching), hospital bed size, hospital ownership (government, private nonprofit, or private investor), and region (East, Midwest, South, or West).

To evaluate temporal trends in comorbidity, we performed 2 sets of analyses: (1) we assessed rates of obstetric and medical conditions associated with increased maternal risk, comparing their prevalence at the beginning and end of the study period; and (2) we evaluated temporal trends in comorbid risk as measured by the obstetric comorbidity index developed by Bateman et al. This comorbidity index was calculated using a data set consisting of 854,823 completed pregnancies randomly divided into a two-thirds development cohort and a one-third validation cohort. Using the development cohort, a logistic regression model predicting the occurrence of maternal end-organ injury or death during the delivery hospitalization through 30 days postpartum was created using a stepwise selection algorithm that included 24 candidate comorbid conditions and maternal age. The comorbidity index provides weighted scores for individual patients based on the presence of specific diagnosis codes and demographic factors from administrative data. The conditions that comprise the index include severe preeclampsia or eclampsia, congestive heart failure, congenital heart disease, pulmonary hypertension, ischemic heart disease, sickle cell disease, multiple gestation, cardiac valvular disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, maternal age, HIV, mild preeclampsia, drug abuse, placenta previa, chronic renal disease, preexisting hypertension, previous cesarean delivery, gestational hypertension, alcohol abuse, asthma, and preexisting diabetes mellitus; these conditions are weighted relative to their association with severe morbidity. In the initial study validating the comorbidity index, subjects with the lowest score of 0 had a 0.68% risk of severe morbidity whereas a score of >10 was associated with a risk of severe morbidity of 10.9%. This comorbidity index was subsequently validated in an external population.

To determine to what degree temporal trends in maternal risk were driven by low- vs moderate- or high-risk patients, we determined rates of severe morbidity over the study period for both the entire cohort and individually for patients at low, moderate, and high risk based on the obstetric comorbidity index. Low-risk patients were classified as those with a score of 0-2, moderate-risk patients a score of 3-4, and high-risk patients a score of ≥5. The overall outcome of severe morbidity in this analysis was based on the presence of any ≥1 of 15 diagnoses of acute organ injury and critical illness also analyzed in the validated obstetric comorbidity index: acute heart failure, acute liver disease, acute myocardial infarction, acute renal failure, coma, delirium, disseminated intravascular coagulation, puerperal cerebrovascular disorders, pulmonary edema, pulmonary embolism, sepsis, shock, status asthmaticus, and status epilepticus.

To determine temporal trends in how risk for severe morbidity was associated with specific diagnoses associated with maternal mortality, we individually evaluated risk for severe morbidity in the presence of a diagnosis of: (1) antepartum or postpartum hemorrhage, (2) maternal infection, (3) hypertensive diseases of pregnancy, and (4) underlying medical conditions. Underlying medical conditions included preexisting diabetes, chronic hypertension, chronic renal disease, asthma, acquired and congenital heart disease, sickle cell disease, pulmonary hypertension, systemic lupus erythematosus, HIV, and cystic fibrosis. Maternal infection included medical conditions such as pyelonephritis, pneumonia, influenza, systemic inflammatory response syndrome, and other conditions.

Statistical analysis

Adjusted risk ratios for severe morbidity accounting for demographic, hospital, and comorbid risk were derived from fitting a log-linear regression models based on a Poisson distribution and a log-link function. To account for both (1) subjects clustered within hospitals and (2) changes in temporal prevalence of severe maternal morbidity, the regression models were estimated based on the method of generalized estimating equations. In this model, year of delivery nested by hospital was treated as the clustering parameter (therefore, temporal trends are not reported from this model). We then repeated the regression model by declaring year of delivery as a fixed effects parameter (and no longer nested temporal trends) with clustering by hospital. We utilized this latter model to be able to report risk ratios for temporal changes in severe morbidity (results shown in Appendix Figure 1 , Appendix Figure 2 , and Appendix Table ).

Finally, as a reference, for hospitals performing ≥1000 deliveries per year, we calculated: (1) trends in comorbidity scores; (2) the relative increase in severe morbidity risk by comorbidity score; (3) the increase in risk of severe morbidity overall; and (4) risk of severe maternal morbidity associated with hemorrhage, infection, preeclampsia, and medical conditions. We used the χ 2 test to assess the significance of binary outcomes. All statistical analyses were performed using software (SAS, Version 9.4; SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Materials and Methods

For this analysis we used data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The NIS is the largest publicly available, all-payer inpatient database in the United States and it contains a sample of approximately 20% of all hospitals nationally, selected to generate a sample that is representative of all US hospitalizations. Through 2011, the data feature all discharge claims in individual hospitals. The hospitals sampled in the NIS include academic, community, nonfederal, general, and specialty-specific centers across the United States. Approximately 8 million hospital stays from a total of 45 states in 2010 are included in the NIS. As this data set was entirely deidentified, exemption status was given by the institutional review board from Columbia University. This permission was obtained prior to commencement of the study.

Hospitals were dichotomized based on whether they performed <1000 or ≥1000 deliveries per year. Prior analyses have used varying obstetric volume cutoffs ; the volume categories used in this analysis were chosen because: (1) they represent easily interpretable and clinically meaningful distinctions in obstetric volume; and (2) centers performing <1000 deliveries annually account approximately for the lowest delivery volume quintile nationally. To identify hospitals, we calculated the total number of deliveries over the study period and divided this by the number of years in which a hospital had at least 1 delivery. Hospital classification was based on whether mean delivery volume was <1000 or ≥1000 per year. Deliveries were identified based on whether International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision billing codes v27.x and/or 650 were present. These codes have been shown to identify >95% of all delivery hospitalizations. This study included births from 1998 through 2011, as NIS data after 2011 do not include all discharges from individual centers. Besides hospital volume, other hospital characteristics included location (urban vs rural), teaching status (teaching vs nonteaching), hospital bed size, hospital ownership (government, private nonprofit, or private investor), and region (East, Midwest, South, or West).

To evaluate temporal trends in comorbidity, we performed 2 sets of analyses: (1) we assessed rates of obstetric and medical conditions associated with increased maternal risk, comparing their prevalence at the beginning and end of the study period; and (2) we evaluated temporal trends in comorbid risk as measured by the obstetric comorbidity index developed by Bateman et al. This comorbidity index was calculated using a data set consisting of 854,823 completed pregnancies randomly divided into a two-thirds development cohort and a one-third validation cohort. Using the development cohort, a logistic regression model predicting the occurrence of maternal end-organ injury or death during the delivery hospitalization through 30 days postpartum was created using a stepwise selection algorithm that included 24 candidate comorbid conditions and maternal age. The comorbidity index provides weighted scores for individual patients based on the presence of specific diagnosis codes and demographic factors from administrative data. The conditions that comprise the index include severe preeclampsia or eclampsia, congestive heart failure, congenital heart disease, pulmonary hypertension, ischemic heart disease, sickle cell disease, multiple gestation, cardiac valvular disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, maternal age, HIV, mild preeclampsia, drug abuse, placenta previa, chronic renal disease, preexisting hypertension, previous cesarean delivery, gestational hypertension, alcohol abuse, asthma, and preexisting diabetes mellitus; these conditions are weighted relative to their association with severe morbidity. In the initial study validating the comorbidity index, subjects with the lowest score of 0 had a 0.68% risk of severe morbidity whereas a score of >10 was associated with a risk of severe morbidity of 10.9%. This comorbidity index was subsequently validated in an external population.

To determine to what degree temporal trends in maternal risk were driven by low- vs moderate- or high-risk patients, we determined rates of severe morbidity over the study period for both the entire cohort and individually for patients at low, moderate, and high risk based on the obstetric comorbidity index. Low-risk patients were classified as those with a score of 0-2, moderate-risk patients a score of 3-4, and high-risk patients a score of ≥5. The overall outcome of severe morbidity in this analysis was based on the presence of any ≥1 of 15 diagnoses of acute organ injury and critical illness also analyzed in the validated obstetric comorbidity index: acute heart failure, acute liver disease, acute myocardial infarction, acute renal failure, coma, delirium, disseminated intravascular coagulation, puerperal cerebrovascular disorders, pulmonary edema, pulmonary embolism, sepsis, shock, status asthmaticus, and status epilepticus.

To determine temporal trends in how risk for severe morbidity was associated with specific diagnoses associated with maternal mortality, we individually evaluated risk for severe morbidity in the presence of a diagnosis of: (1) antepartum or postpartum hemorrhage, (2) maternal infection, (3) hypertensive diseases of pregnancy, and (4) underlying medical conditions. Underlying medical conditions included preexisting diabetes, chronic hypertension, chronic renal disease, asthma, acquired and congenital heart disease, sickle cell disease, pulmonary hypertension, systemic lupus erythematosus, HIV, and cystic fibrosis. Maternal infection included medical conditions such as pyelonephritis, pneumonia, influenza, systemic inflammatory response syndrome, and other conditions.

Statistical analysis

Adjusted risk ratios for severe morbidity accounting for demographic, hospital, and comorbid risk were derived from fitting a log-linear regression models based on a Poisson distribution and a log-link function. To account for both (1) subjects clustered within hospitals and (2) changes in temporal prevalence of severe maternal morbidity, the regression models were estimated based on the method of generalized estimating equations. In this model, year of delivery nested by hospital was treated as the clustering parameter (therefore, temporal trends are not reported from this model). We then repeated the regression model by declaring year of delivery as a fixed effects parameter (and no longer nested temporal trends) with clustering by hospital. We utilized this latter model to be able to report risk ratios for temporal changes in severe morbidity (results shown in Appendix Figure 1 , Appendix Figure 2 , and Appendix Table ).

Finally, as a reference, for hospitals performing ≥1000 deliveries per year, we calculated: (1) trends in comorbidity scores; (2) the relative increase in severe morbidity risk by comorbidity score; (3) the increase in risk of severe morbidity overall; and (4) risk of severe maternal morbidity associated with hemorrhage, infection, preeclampsia, and medical conditions. We used the χ 2 test to assess the significance of binary outcomes. All statistical analyses were performed using software (SAS, Version 9.4; SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

A total of 2,300,279 deliveries occurred in hospitals with annual delivery volume of <1000 and were included in the analysis; these deliveries represented 20.04% of the 11,478,439 deliveries in the entire NIS. There were 7849 cases (0.34%) of severe morbidity in low-volume hospitals. The demographics of the study cohort are presented in Table 1 . Demographic data for women delivering at hospitals with volumes of ≥1000 deliveries per year are presented as a reference.

| Volume category | <1000 | ≥1000 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| All deliveries | 230,0279 | 20.0 | 9,178,160 | 80.0 |

| Age, y | ||||

| <20 | 310,037 | 13.5 | 911,365 | 9.9 |

| 20–24 | 688,081 | 29.9 | 2,114,992 | 23.0 |

| 25–29 | 636,193 | 27.7 | 2,504,042 | 27.3 |

| 30–34 | 436,135 | 19.0 | 2,257,763 | 24.6 |

| ≥35 | 229,833 | 10.0 | 1,389,998 | 15.1 |

| Discharge year | ||||

| 1998 | 174,725 | 7.6 | 531,031 | 6.2 |

| 1999 | 170,121 | 7.4 | 591,410 | 6.6 |

| 2000 | 168,536 | 7.3 | 641,571 | 7.1 |

| 2001 | 167,922 | 7.3 | 612,915 | 6.8 |

| 2002 | 168,187 | 7.3 | 677,743 | 7.4 |

| 2003 | 166,958 | 7.3 | 668,889 | 7.3 |

| 2004 | 164,364 | 7.2 | 693,572 | 7.5 |

| 2005 | 165,755 | 7.2 | 684,610 | 7.4 |

| 2006 | 159,448 | 6.9 | 705,839 | 7.5 |

| 2007 | 169,366 | 7.4 | 751,178 | 8.0 |

| 2008 | 160,232 | 7.0 | 702,005 | 7.7 |

| 2009 | 167,399 | 7.3 | 650,112 | 7.1 |

| 2010 | 146,827 | 6.4 | 625,579 | 6.8 |

| 2011 | 150,439 | 6.5 | 641,706 | 7.0 |

| Household income | ||||

| Lowest quartile | 541,529 | 23.5 | 1,714,324 | 18.7 |

| Second quartile | 805,122 | 35.0 | 1,983,353 | 21.6 |

| Third quartile | 560,368 | 24.4 | 2,322,740 | 25.3 |

| Highest quartile | 343,170 | 14.9 | 3,002,406 | 32.7 |

| Unknown | 50,090 | 2.2 | 155,337 | 1.7 |

| Insurance status | ||||

| Medicare | 14,454 | 0.6 | 40,274 | 0.4 |

| Medicaid | 1,040,808 | 45.3 | 3,507,879 | 38.2 |

| Private | 1,091,388 | 47.5 | 5,054,528 | 55.1 |

| Self-pay | 73,563 | 3.2 | 316,769 | 3.5 |

| Other | 71,877 | 3.1 | 241,549 | 2.6 |

| Unknown | 8189 | 0.4 | 17,161 | 0.2 |

| Race | ||||

| White | 1,174,850 | 51.1 | 3,516,551 | 38.3 |

| Black | 152,072 | 6.6 | 1,031,654 | 11.2 |

| Hispanic | 204,391 | 8.9 | 1,847,701 | 20.1 |

| Other/unknown | 768,966 | 33.4 | 2,782,254 | 30.3 |

| Hospital location | ||||

| Rural | 1,119,337 | 48.7 | 351,827 | 3.8 |

| Urban | 1,177,285 | 51.2 | 8,796,570 | 95.8 |

| Unknown | 3567 | 0.2 | 29,763 | 0.3 |

| Hospital region | ||||

| Northeast | 334,229 | 14.5 | 1,496,788 | 16.3 |

| Midwest | 741,243 | 32.2 | 1,649,318 | 18.0 |

| South | 832,760 | 36.2 | 3,502,130 | 38.2 |

| West | 392,047 | 17.0 | 2,529,924 | 27.6 |

| Hospital teaching | ||||

| Nonteaching | 2,057,445 | 89.4 | 4,227,717 | 46.1 |

| Teaching | 239,177 | 10.4 | 4,920,680 | 53.6 |

| Unknown | 3657 | 0.2 | 29,763 | 0.3 |

| Comorbidity index | ||||

| 0 | 1,601,413 | 69.6 | 5,854,331 | 63.8 |

| 1 | 454,098 | 19.8 | 1,987,606 | 21.7 |

| 2 | 169,798 | 7.4 | 842,092 | 9.2 |

| 3 | 42,554 | 1.9 | 252,740 | 2.8 |

| 4 | 11,449 | 0.5 | 82,240 | 0.9 |

| ≥5 | 20,134 | 0.9 | 154,557 | 1.7 |

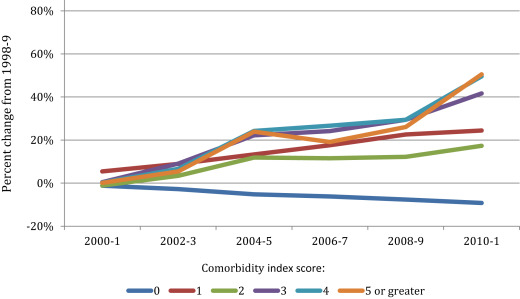

The majority of women delivering at hospitals performing <1000 deliveries per year (89.4%) had a comorbidity index score of 0 or 1 representing low risk for severe morbidity. However, the composition of comorbidity scores changed over the study period. As Figure 1 demonstrates, the proportion of patients with a comorbidity score of 0 decreased 9.2% from 1998 through 1999 to 2010 through 2011 ( P < .01). Conversely, the proportion of all other comorbidity scores between 1 and ≥5 increased over the course of the study. The proportion of patients in the highest risk category groups (those with a comorbidity score of 4 or ≥5) increased by approximately 50% by 2010 through 2011 compared to 1998 through 1999 ( Table 2 ) ( P < .01). Appendix Figure 1 demonstrates changes in comorbidity scores for hospitals with volume ≥1000. Similar to low-volume hospitals, the proportion of patients with a score of 0 decreased over the study period (11.8%). In comparison, the proportion of patients with scores of 1 to ≥5 increased with the proportion of patients with a score of ≥5 rising 82.3%.

| Risk factors | 1998 through 1999 n = 344,846 | 2010 through 2011 n = 297,266 | Percent change |

|---|---|---|---|

| % (n) | |||

| Maternal age ≥40 y a | 1.62 (5577) | 1.78 (5301) | ↑ 9.9 |

| Placenta previa | 0.36 (1246) | 0.38 (1141) | ↑ 5.6 |

| Previous cesarean delivery a | 11.27 (38,848) | 15.7 (46,678) | ↑ 39.3 |

| Multiple gestation a | 1.00 (3437) | 1.13 (3370) | ↑ 13.0 |

| Gestational hypertension a | 2.28 (7863) | 3.42 (10,161) | ↑ 50.0 |

| Mild or unspecified preeclampsia a | 2.42 (8361) | 2.54 (7539) | ↑ 5.0 |

| Severe preeclampsia or eclampsia a | 0.61 (2119) | 0.89 (2637) | ↑ 46.0 |

| Superimposed preeclampsia or eclampsia a | 0.14 (497) | 0.32 (940) | ↑ 128.6 |

| Chronic hypertension a | 0.71 (2432) | 1.52 (4525) | ↑ 114.0 |

| Preexisting diabetes a | 0.40 (1396) | 0.71 (2114) | ↑ 77.5 |

| Gestational diabetes a | 2.7 (9317) | 5.15 (15,308) | ↑ 90.7 |

| Asthma a | 0.90 (3117) | 2.76 (8194) | ↑ 206.7 |

| Chronic renal disease a | 0.11 (387) | 0.23 (669) | ↑ 109.1 |

| Drug abuse a | 0.28 (952) | 0.36 (1078) | ↑ 28.6 |

| Alcohol abuse a | 0.09 (326) | 0.11 (314) | ↑ 22.2 |

| Comorbidity score a | |||

| 0 | 72.9 (251,428) | 66.21 (196,766) | ↓ 9.2 |

| 1 | 17.49 (60,315) | 21.77 (64,688) | ↑ 24.5 |

| 2 | 6.86 (23,652) | 8.05 (23,910) | ↑ 17.3 |

| 3 | 1.57 (5428) | 2.23 (6624) | ↑ 42.0 |

| 4 | 0.42 (1445) | 0.63 (1862) | ↑ 50.0 |

| ≥5 | 0.75 (2576) | 1.12 (3341) | ↑ 49.3 |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree