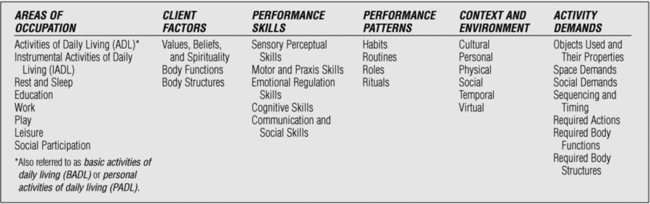

1 JEAN W. SOLOMON and JANE CLIFFORD O’BRIEN After studying this chapter, the reader will be able to accomplish the following: • Describe the Centennial Vision of the American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA). • Describe the basics of the Occupational Therapy Practice Framework: Domain and Process, 2nd edition, and its relationship to clinical practice. • Recognize eight subject areas in which entry-level certified occupational therapy assistants need to have general knowledge. • Describe the four levels at which registered occupational therapists supervise occupational therapy assistants. • Define service competency and give examples of ways it may be obtained. • Discuss AOTA’s Code of Ethics and apply the code to case scenarios. • Define and give examples of the different types of scholarship. During the past 20 years, significant changes have occurred in the provision of pediatric OT services.2,3,8 Numerous federal laws that expand the services available to infants, children, and adolescents who have special needs or disabilities have been implemented. Approximately 20% of all OT assistants (OTAs) work in pediatric settings.12 OT practitioners provide pediatric services in medical settings such as outpatient clinics and hospitals, as well as in community settings such as schools, homes, and daycare centers.12 Because numerous practitioners work with infants, children, and adolescents, it is important that both entry-level occupational therapists and OTAs have a solid foundation in pediatrics. The AOTA has identified eight subject areas that must be included in any pediatric OT curriculum.4,8 An entry-level OT practitioner must have knowledge in the following areas: Normal development: OT practitioners working with children who have special needs or atypical development patterns must have a firm foundation in the knowledge of normal development in order to understand children and base interventions. Importance of families in the OT process: Families are the most consistent participants on the pediatric team. Understanding the needs of families and children is essential to the therapeutic process. Specific pediatric diagnoses: Pediatric OT practitioners use knowledge of specific pediatric diagnoses to determine which tools and methods are the most appropriate for assessment and intervention. OT practice models (i.e., frames of reference): Understanding models of practice and frames of reference is necessary for organizing and developing interventions based on evidence from the profession. Knowledge of the principles and techniques allows practitioners to develop interventions for children with a variety of diagnoses. Assessments appropriate for a child who has a specific disability or diagnosis: OT practitioners work with children with a number of different diagnoses. Therefore, OT practitioners must be knowledgeable about a variety of assessments to determine the specific needs of children. Assessments may also be used to measure outcomes of interventions. Age-appropriate activities: OT practitioners working with children need to adjust therapy activities to suit the age and developmental needs of a particular child. Thus, knowledge of a range of age-appropriate activities is essential to practice. Differences among systems in which OT services are provided: OT services are provided in a variety of settings. These settings exist within systems that have different missions. OT practitioners work within these settings and design interventions to meet the needs of their clients as well as those of the system. For example, children receiving services in a public school system require educationally relevant therapy goals and objectives, whereas children receiving services in a hospital require medically necessary goals and objectives. Assistive technology: OT practitioners who work with infants, children, and adolescents who have disabilities or special needs must have knowledge of the range of assistive technologies that promote safe and independent living. In 2017, the profession of OT will be 100 years old. AOTA has adopted a Centennial Vision that recognizes OT as a science-driven and evidence-based profession that continues to meet the occupational needs of clients, communities, and populations. AOTA is actively promoting OT practitioners to assume leadership roles and contribute to outcome databases that support evidence-based practice.1 The centennial vision addresses areas of pediatric practice, including the health and wellness of children and youth (including programs to prevent childhood obesity), and the psychosocial needs of children and youth.7 AOTA, through its vision, suggests that practitioners continue to provide evidence of the importance of occupation and intervention.1 The vision encourages practitioners to become leaders in the profession and to support the profession through participation in AOTA, scholarship (at many different levels) and clinical practice.1 The Occupational Therapy Practice Framework (OTPF) defines both the process and domain of occupational therapy.6 Subsequent chapters discuss the OT process and domain in detail. The OTPF was developed to assist practitioners in defining the process and domains of OT.6 The OTPF is designed to be used by occupational therapists, certified occupational therapists, consumers, and health care providers. Figure 1-1 illustrates the framework. The OTPF defines the process of OT as a dynamic, ongoing process that includes evaluation, intervention, and outcome. Evaluation provides an understanding of the clients’ problems, occupational history, patterns, and assets.6 Intervention includes the plan (based on selected theories, models of practice, frames of reference, and evidence), implementation, and review. Outcome refers to how well the goals are achieved. The domain of OT practice is occupation, defined as “activities…of everyday life, named, organized, and given value and meaning by individuals and a culture. Occupation is everything people do to occupy themselves, including looking after themselves, enjoying life, and contributing to the social and economic fabric of their communities.” 11 (p.32 ). See Figure 1-2 for an illustration of the process. Occupation is viewed as both a means and an end.6 Using occupation as a means includes such things as participating in school activities to improve the ability to function in school; it follows the “learning by doing” philosophy. Occupation is also viewed as an end in that the goal of therapy sessions is to enable the child to function in his or her occupations. For example, therapy sessions focusing on handwriting skills are intended to improve the child’s ability to function in an academic occupation. The OTPF defines the areas of occupation as activities of daily living (ADLs), instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs), education, work, play, leisure, and social participation.6 Clinicians examine performance skills (motor, processing and communication) and patterns (habits, routines, roles) associated with areas of occupation. Clinicians analyze the demands of activities and client factors required for an occupation in order to develop intervention plans. However, the OTPF focuses on the occupation instead of its components. Equally important is an examination of the contexts and environments in which an occupation occurs. According to the OTPF, these contexts and environments are cultural, personal, temporal, virtual, physical, and social (Table 1-1). Contexts influence how an occupation is viewed, performed, and evaluated. For example, when considering the temporal context, practitioners would expect differences in social behavior between a 2-year-old toddler and 6-year-old child. TABLE 1-1 *Context refers to a variety of interrelated conditions within and surrounding the client that influence performance. 1World Health Organization: International classification of functioning, disability and health (ICF), Geneva, Switzerland, 2001, WHO. 2Crepeau E, Cohn E, Boyt-Schell B: Willard and Spackman’s occupational therapy, 11th edition, Philadelphia, 2009, Lippincott Williams and Wilkins. Adapted from the American Occupational Therapy Association: Occupational therapy practice framework: Domain and process, 2nd edition, Am J Occup Ther 62:625–683, 2008.

Scope of practice

Centennial vision

Occupational therapy practice framework

CONTEXT

DEFINITION

EXAMPLE

Cultural

Customs, beliefs, activity patterns, behavior standards, and expectations accepted by the society of which the individual is a member. Includes political aspects, such as laws that affect access to resources and affirm personal rights. Also includes opportunities for education, employment, and economic support.

Ethnicity, family attitude, beliefs, values

Personal

“[F]eatures of the individual that are not part of a health condition or health status.”1 Personal context includes age, gender, socioeconomic status, and educational status.

25-year-old unemployed

Temporal

“Location of occupational performance in time.”2

Stages of life, time of day, time of year, duration

Virtual

Environment in which communication occurs by means of airways or computers and an absence of physical contact.

Realistic simulation of an environment, chat rooms, radio transmissions

Physical

Nonhuman aspects of contexts. Includes accessibility to and performance within environments having natural terrain, plants, animals, buildings, furniture, objects, tools, or devices.

Objects, built environment, natural environment, geographic terrain, sensory qualities of environment

Social

Availability and expectations of significant individuals, such as spouse, friends, and caregivers. Also includes larger social groups that are influential in establishing norms, role expectations, and social routines.

Relationships with individuals, groups, or organizations; relationships with systems (political, economic, institutional)

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree