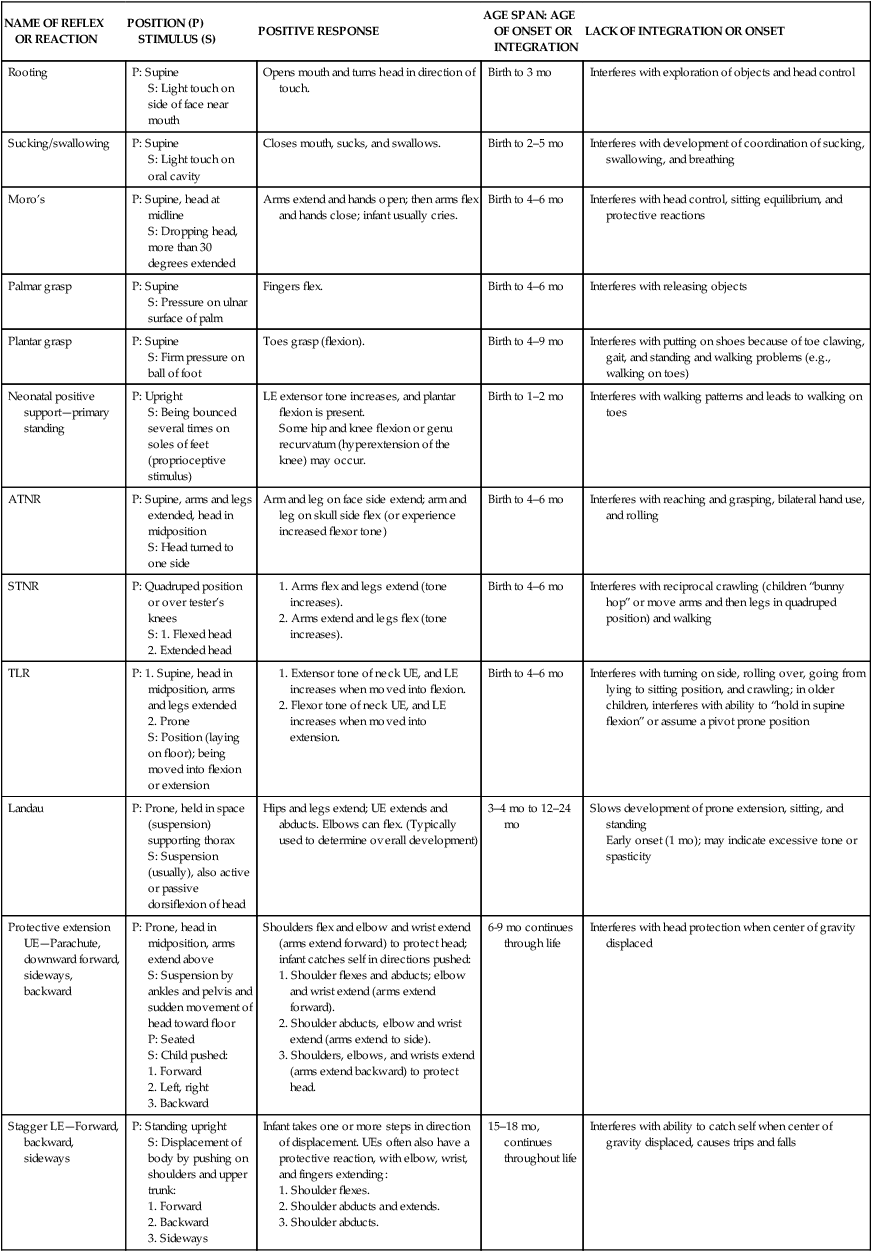

7 After studying this chapter, the reader will be able to accomplish the following: • Describe significant physiological changes that occur at each stage of development. • Identify the sequences of motor skill development (gross and fine motor). • Outline the stages of process development (cognitive) as defined by Piaget’s theory. • Describe the issues in each phase of communication and interaction development (psychosocial development) using the theories of Erikson and Greenspan. From birth through adolescence, the child progresses through periods of development. Development that occurs within each period is described in the literature in terms of physiologic, motor, cognitive, language, and psychosocial domains. In the Occupational Therapy Practice Framework, the occupational performance skills are motor skills (gross and fine motor skills), process skills (cognition), and communication/interaction skills (language and psychosocial) (Box 7-1).2 Deficits in any of these skills may interfere with the child’s performance in the areas of self-care, play, education, and social participation. The normal developmental sequences are presented in this chapter to assist occupational therapy (OT) practitioners in identifying potential deficits or delays. Sequences may vary, and the physical, temporal, social, and cultural aspects of the environment may affect developmental progression. The newborn’s average weight at birth is 7 lb, 2 oz and the average length between 19 and 22 inches. The appearance of the newborn may be characterized by a covering comprising a layer of fluid called vernix caseosa; a large, bumpy head; a flat, “board” nose; reddish skin; puffy eyes; external breasts; and fine hair called lanugo covering the body.13 At 1 minute after birth, the newborn’s physiological status is tested using the Apgar scoring system, which rates each of the following five areas on a scale of 0 to 2: (1) color, (2) heart rate, (3) reflex irritability, (4) muscle tone, and (5) respiratory effort. The scores are computed at 1 and 5 minutes after birth. The closer the total score (sum of scores for the five areas) is to 10, the better is the condition of the newborn; scores of 6 or less indicate the need for intervention.12 The infant’s first 3 months of life are characterized by constant physiologic adaptations. Structural changes in the newborn’s circulatory system include the expansion of the lungs and increased efficiency of blood flow to the heart. The developing central nervous system (CNS) participates in the body’s regulation of sleep, digestion, and temperature.10 Physical growth is dramatic—from birth to 6 months of age, infants experience a more rapid rate of growth than at any other time, except during gestation.19 During the first year, infants triple their body weight, and their height increases by 10 to 12 inches. Their body shape changes, and by 4 months the sizes of their heads and bodies are more proportionate. By 12 months, average infants weigh 21 to 22 lb and are 29 to 30 inches tall. During the second year of life, physical growth slows. By 24 months, an average toddler weighs about 27 lb and is 34 inches tall. The posture of toddlers is characterized by lordosis (forward curvature of the spine) and a protruding abdomen, which toddlers retain well into the third year.33 At 4 months, sleep patterns begin to be regulated, and some infants may sleep through the night. By 8 months, the average infant sleeps 12 to 13 hours per day, but the range can vary from 9 to 18 hours per day. By 6 to 7 months, the average infant acquires the first tooth, a lower incisor. As a result, saliva production increases, which leads to drooling. At approximately 8 months, the upper central incisor teeth begin to surface, at 9 months the upper lateral incisors appear, and at 12 months the first lower molars are seen.28 Brazelton identified six behavioral states observed in the newborn: (1) deep sleep; (2) light sleep; (3) drowsy or semidozing; (4) alert, actively awake; (5) fussy; and (6) crying.9 The infant’s state should be noted when observing the way he or she responds to stimulation.13 Newborns have vision at birth and can see objects best from about 8 inches away, which is the typical distance between the caregiver’s face and the infant’s.29 By the first month of life, an infant shows a preference for patterns and can distinguish between colors. By 3 months, visual acuity develops enough to allow distinction between a picture of a face and a real face.10 By 12 months, the infant’s visual acuity is about 20/100 to 20/50.24 Hearing is well developed in newborns and continues to improve as they grow. They tend to respond strongly to the mother’s voice.25 During the first 2 months, infants respond to sound with random body movements. At 3 months, they move their eyes in the direction of sound.10 At 6 months, they localize sounds to the left and right.5 At birth, newborns are able to taste sweet, sour, and bitter substances. Between birth and 3 months, infants are able to differentiate between pleasant and noxious odors. They are very sensitive to touch, cold and heat, pain, and pressure; one of the most important stimuli for infants from birth to 3 months is skin contact and warmth.27 Holding and swaddling the infant provide skin contact and maintain the infant’s body temperature.13 The newborn’s body is characterized by physiologic flexion, a position of extremity and trunk flexion.8 This flexion tends to keep the infant in a compact position and provides a base of stability for random movements to occur. These movements are characterized by a motion called random burst, in which everything moves as a unit.1 The newborn has numerous primitive reflexes, which are genetically transmitted survival mechanisms. These automatic responses to stimuli help the newborn adapt to the environment. Primitive reflexes are controlled by lower levels of the CNS. As higher levels of the CNS mature, higher systems inhibit the expression of primitive reflexes. As infants learn about the environment, primitive reflexes are integrated into their overall postural mechanism, with the more mature righting and equilibrium responses that dominate their movements.34 Under stress, these reflexes may be partially present, but they are never obligatory in normal development. Some primitive reflexes are present at birth, whereas others emerge later in the infant’s development (Table 7-1). TABLE 7-1 Adapted from Alexander R, Boehme R, Cupps B: Normal development of functional motor skills, Tucson, AR, 1993, Therapy Skill Builders; Bly L: Motor skills acquisition in the first year: An illustrated guide to normal development, Tucson, AR, 1994, Therapy Skill Builders; Fiorentino MR: Reflex testing methods for evaluating CNS development, ed 2, Springfield, IL, 1981, Charles C Thomas; Simon CJ, Daub MM: Human development across the life span. In Hopkins JL, Smith HD, editors: Willard and Spackman’s occupational therapy, ed 8, Philadelphia, 1993, Lippincott. As shown in Table 7-2, infants’ gross motor skills become gradually more complex as they develop.1,8,13 Infants begin to combine basic reflexive movements with higher cognitive and physiologic functioning to control these movements in the environment (Box 7-2). Between birth and 2 months, infants can turn their heads from side to side while in prone and supine positions. As physiologic flexion diminishes, they appear more hypotonic (have less muscular and postural tone), and the movements of each side of their body appear asymmetrical. The asymmetrical tonic neck reflex (ATNR) holds infants’ heads to one side. By 4 months, they can raise and rotate their heads to look at their surroundings. In the supine position (on the back), 4-month-old infants begin to bring their hands to their knees and can deliberately roll from the supine position to the side. The increased head and trunk control observed at this age is the result of emerging righting reactions and better postural control (see Box 7-2). At 5 months, when pulled to a sitting position, infants can bring their heads forward without lagging. By 6 months, they can shift their weight to free extremities to reach for objects while in the prone position (on the stomach). In the supine position, 6-month-old infants can bring their feet to their mouths and are able to sit by themselves for short periods. At 7 to 8 months, they are able to push themselves from the prone position to the sitting position, roll over at will, and crawl on their stomachs. Between 6 and 9 months, infants develop upper extremity protective extension reactions that allow them to catch themselves when pushed off balance (Figure 7-1). From 7 to 21 months, they develop equilibrium reactions that allow them to maintain their center of gravity over their base of support; these reactions are critical for transitional movements patterns (i.e., movements from one position to another) and ambulation (see Box7-2; Figure 7-2). At 10 to 11 months, infants are practicing and enjoying creeping. By 12 months, they are learning to shift their weight and step to one side by cruising around furniture. At 13 or 14 months most infants take their first steps, and between 12 and 18 months they spend much of their time practicing motor skills by walking, jumping, running, and kicking. Mobility changes infants’ perceptions of their environment. A chair is a one-dimensional object in the eyes of a 6 month old; it is only when the infant can finally climb over, under, and around the chair that he or she discovers what a chair really is.18 TABLE 7-2 Normal Development of Sensorimotor Skills ATNR, asymmetrical tonic neck reflex. *From this point on, skills learned during the first 24 months are further refined. Adapted from Alexander R, Boehme R, Cupps B: Normal development of functional motor skills, Tucson, AR, 1993, Therapy Skill Builders; Case-Smith J, Shortridge SD: The developmental process: Prenatal to adolescence. In Case-Smith J, Allen AS, Pratt PN, editors: Occupational therapy for children, ed 3, St Louis, 1996, Mosby; Clark GF: Oral-motor and feeding issues. In Royeen CB, editor: AOTA self-study series: Classroom applications for school-based practice, Rockville, MD, 1993, American Occupational Therapy Association; Erhardt RP: Developmental hand dysfunction: Theory, assessment, and treatment, ed 2, Tucson, AR, 1994 Therapy Skill Builders.

Development of occupational performance skills

Infancy

Physiologic development

Motor development

Sensory skills

Gross motor skills

NAME OF REFLEX OR REACTION

POSITION (P)

STIMULUS (S)

POSITIVE RESPONSE

AGE SPAN: AGE OF ONSET OR INTEGRATION

LACK OF INTEGRATION OR ONSET

Rooting

P: Supine

S: Light touch on side of face near mouth

Opens mouth and turns head in direction of touch.

Birth to 3 mo

Interferes with exploration of objects and head control

Sucking/swallowing

P: Supine

S: Light touch on oral cavity

Closes mouth, sucks, and swallows.

Birth to 2–5 mo

Interferes with development of coordination of sucking, swallowing, and breathing

Moro’s

P: Supine, head at midline

S: Dropping head, more than 30 degrees extended

Arms extend and hands open; then arms flex and hands close; infant usually cries.

Birth to 4–6 mo

Interferes with head control, sitting equilibrium, and protective reactions

Palmar grasp

P: Supine

S: Pressure on ulnar surface of palm

Fingers flex.

Birth to 4–6 mo

Interferes with releasing objects

Plantar grasp

P: Supine

S: Firm pressure on ball of foot

Toes grasp (flexion).

Birth to 4–9 mo

Interferes with putting on shoes because of toe clawing, gait, and standing and walking problems (e.g., walking on toes)

Neonatal positive support—primary standing

P: Upright

S: Being bounced several times on soles of feet (proprioceptive stimulus)

LE extensor tone increases, and plantar flexion is present.

Some hip and knee flexion or genu recurvatum (hyperextension of the knee) may occur.

Birth to 1–2 mo

Interferes with walking patterns and leads to walking on toes

ATNR

P: Supine, arms and legs extended, head in midposition

S: Head turned to one side

Arm and leg on face side extend; arm and leg on skull side flex (or experience increased flexor tone)

Birth to 4–6 mo

Interferes with reaching and grasping, bilateral hand use, and rolling

STNR

P: Quadruped position or over tester’s knees

S: 1. Flexed head

2. Extended head

Birth to 4–6 mo

Interferes with reciprocal crawling (children “bunny hop” or move arms and then legs in quadruped position) and walking

TLR

P: 1. Supine, head in midposition, arms and legs extended

2. Prone

S: Position (laying on floor); being moved into flexion or extension

Birth to 4–6 mo

Interferes with turning on side, rolling over, going from lying to sitting position, and crawling; in older children, interferes with ability to “hold in supine flexion” or assume a pivot prone position

Landau

P: Prone, held in space (suspension) supporting thorax

S: Suspension (usually), also active or passive dorsiflexion of head

Hips and legs extend; UE extends and abducts. Elbows can flex. (Typically used to determine overall development)

3–4 mo to 12–24 mo

Slows development of prone extension, sitting, and standing

Early onset (1 mo); may indicate excessive tone or spasticity

Protective extension UE—Parachute, downward forward, sideways, backward

P: Prone, head in midposition, arms extend above

S: Suspension by ankles and pelvis and sudden movement of head toward floor

P: Seated

S: Child pushed:

Shoulders flex and elbow and wrist extend (arms extend forward) to protect head; infant catches self in directions pushed:

6-9 mo continues through life

Interferes with head protection when center of gravity displaced

Stagger LE—Forward, backward, sideways

P: Standing upright

S: Displacement of body by pushing on shoulders and upper trunk:

Infant takes one or more steps in direction of displacement. UEs often also have a protective reaction, with elbow, wrist, and fingers extending:

15–18 mo, continues throughout life

Interferes with ability to catch self when center of gravity displaced, causes trips and falls

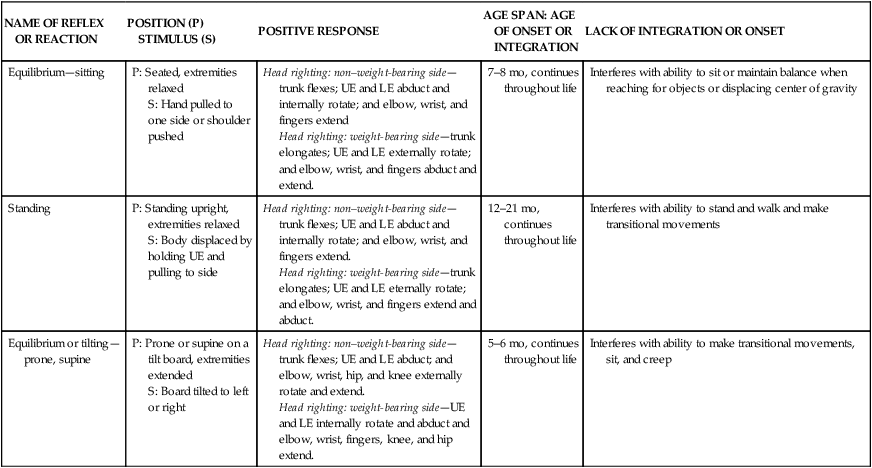

Equilibrium—sitting

P: Seated, extremities relaxed

S: Hand pulled to one side or shoulder pushed

Head righting: non–weight-bearing side—trunk flexes; UE and LE abduct and internally rotate; and elbow, wrist, and fingers extend

Head righting: weight-bearing side—trunk elongates; UE and LE externally rotate; and elbow, wrist, and fingers abduct and extend.

7–8 mo, continues throughout life

Interferes with ability to sit or maintain balance when reaching for objects or displacing center of gravity

Standing

P: Standing upright, extremities relaxed

S: Body displaced by holding UE and pulling to side

Head righting: non–weight-bearing side—trunk flexes; UE and LE abduct and internally rotate; and elbow, wrist, and fingers extend.

Head righting: weight-bearing side—trunk elongates; UE and LE eternally rotate; and elbow, wrist, and fingers extend and abduct.

12–21 mo, continues throughout life

Interferes with ability to stand and walk and make transitional movements

Equilibrium or tilting—prone, supine

P: Prone or supine on a tilt board, extremities extended

S: Board tilted to left or right

Head righting: non–weight-bearing side—trunk flexes; UE and LE abduct; and elbow, wrist, hip, and knee externally rotate and extend.

Head righting: weight-bearing side—UE and LE internally rotate and abduct and elbow, wrist, fingers, knee, and hip extend.

5–6 mo, continues throughout life

Interferes with ability to make transitional movements, sit, and creep

AGE

GROSS MOTOR COORDINATION

FINE MOTOR COORDINATION

BIRTH OR 37-40 WK OF GESTATION

Is dominated by physiologic flexion

Moves entire body into extension

Turns head side to side (protective response)

Keeps head mostly to side while in supine position

Visually regards objects and people

Tends to fist and flex hands across chest during feeding

Displays strong grasp reflex but has no voluntary grasping abilities

Has no voluntary release abilities

1–2 MO

Appears hypertonic as physiologicalal flexion

Practices extension and flexion

Continues to gain control of head

Moves elbows forward toward shoulders while in prone position

Has ATNR with head to side while in supine position

When held in standing position, bears some weight on legs

Displays diminishing grasp reflex

Involuntarily releases after holding them briefly has no voluntary release abilities

3–5 MO

Experiences fading of ATNR and grasp reflex

Has more balance between extension and flexion positions

Has good head control (centered and upright)

Supports self on extended arms while in prone position props self on forearms

Brings hand to feet and feet to mouth while in supine position

Props on arms with little support while seated

Rolls from supine to prone position

Bears some weight on legs when held proximally

Constantly brings hands to mouth

Develops tactile awareness in hands

Reaches more accurately usually with both hands

Palmar grasp

Begins transferring objects from hand to hand

Does not have control of releasing objects may use mouth to assist

6 MO

Has complete head control

Possesses equilibrium reactions

Begins assuming quadruped position

Rolls from prone to supine position

Bounces while standing

Transfers objects from hand to hand while in supine position

Shifts weight and reaches with one hand while in prone position

Reaches with one hand and supports self with other while seated

Reaches to be picked up

Uses radial palmar grasp; begins to use thumb while grasping

Shows visual interest in small objects rakes small objects

Begins to hold objects in one hand

7–9 MO

Shifts weight and reaches while in quadruped position

Creeps

Develops extension, flexion, and rotation movements, and increases number of activities that can be accomplished while seated

May pull to standing position while holding on to support

Reaches with supination

Uses index finger to poke objects

Uses inferior scissors grasp to pick up small objects

Use radial digital grasp to pick up cube

Displays voluntary releases abilities

10–12 MO

Displays good coordination while creeping

Pulls to standing position using legs only

Cruises holding on to support with one hand

Stands independently

Begins to walk independently

Displays equilibrium reactions while standing

Uses superior pincer grasp with fingertip and thumb

Use 3-jaw chuck grasp

Displays controlled release into large containers

13–18 MO

Walks alone

Seldom falls

Begins to go up and down stairs

Displays more precise grasping abilities

Precisely releases objects into small containers

19–24 MO

Displays equilibrium reactions while walking

Runs using a more narrow base support

Uses finger to palm translation of small objects

24–36 MO

Jumps in place*

Uses palm to finger and finger to palm translation of small objects

Displays complex rotation of small objects

Shifts small objects using palmar stabilization

Scribbles

Snips with scissors

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Development of occupational performance skills

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue