Background

Previous studies comparing robotic-assisted laparoscopic surgery to traditional laparoscopic or open surgery in gynecologic oncology have been retrospective. To our knowledge, no prospective randomized trials have thus far been performed on endometrial cancer.

Objective

We sought to prospectively compare traditional and robotic-assisted laparoscopic surgery for endometrial cancer.

Study Design

This was a randomized controlled trial. From December 2010 through October 2013, 101 endometrial cancer patients were randomized to hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, and pelvic lymphadenectomy either by robotic-assisted laparoscopic surgery or by traditional laparoscopy. The primary outcome measure was overall operation time. The secondary outcome measures included total time spent in the operating room, and surgical outcome (number of lymph nodes harvested, complications, and recovery). The study was powered to show at least a 25% difference in the operation time using 2-sided significance level of .05. The differences between the traditional laparoscopy and the robotic surgery groups were tested by Pearson χ 2 test, Fisher exact test, or Mann-Whitney test.

Results

In all, 99 patients were eligible for analysis. The median operation time in the traditional laparoscopy group (n = 49) was 170 (range 126-259) minutes and in the robotic surgery group (n = 50) was 139 (range 86-197) minutes, respectively ( P < .001). The total time spent in the operating room was shorter in the robotic surgery group (228 vs 197 minutes, P < .001). In the traditional laparoscopy group, there were 5 conversions to laparotomy vs none in the robotic surgery group ( P = .027). There were no differences as to the number of lymph nodes removed, bleeding, or the length of postoperative hospital stay. Four (8%) vs no (0%) patients ( P = .056) had intraoperative complications and 5 (10%) vs 11 (22%) ( P = .111) had major postoperative complications in the traditional and robotic surgery groups, respectively.

Conclusion

In patients with endometrial cancer, robotic-assisted laparoscopic surgery was faster to perform than traditional laparoscopy. Also total time spent in the operation room was shorter in the robotic surgery group and all conversions to laparotomy occurred in the traditional laparoscopy group. Otherwise, the surgical outcome was similar between the groups. Robotic surgery offers an effective and safe alternative in the surgical treatment of endometrial cancer.

Introduction

Endometrial carcinoma is globally the sixth most common cancer in women, with 320,000 new cases annually, or 4.8% of cancers in women. The estimated age-standardized incidence rate (World standard) is 8.3 per 100,000 women. The highest incidence rates are found in North America (19.1 per 100,000) and Northern and Western Europe (12.9-15.6 per 100,000). The rates are low in South-Central Asia (2.7 per 100,000) and in most parts of Africa (<5 per 100,000). In developed countries, endometrial cancer is diagnosed often (80%) at International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics stage I and can thus be cured by surgery, albeit followed by adjuvant therapy if high-risk features are encountered. Over the last 20 years, laparotomy has been replaced by minimally invasive laparoscopic techniques, of which robotic-assisted surgery has lately become increasingly popular.

The advantages of robotic-assisted surgery as opposed to conventional laparoscopy have been described in retrospective and observational studies. The 3-dimensional view, the better and more precise visibility of the operation area, the fatigue-resistant properties of robot hands, as well as the better mobility and the greater range of movement of the instrument head all facilitate working with the robot. Because of these advantages, the learning curve is faster than in conventional laparoscopy ; eg, endoscopic suturing technique can be adopted faster. Based on the advantages presented above, robotic-assisted surgery has been adopted widely as the operative treatment of endometrial cancer, but as far as we are aware, it has not been tested in a randomized, controlled setting. The present study was initiated in December 2010 to answer to this obvious unmet need.

Materials and Methods

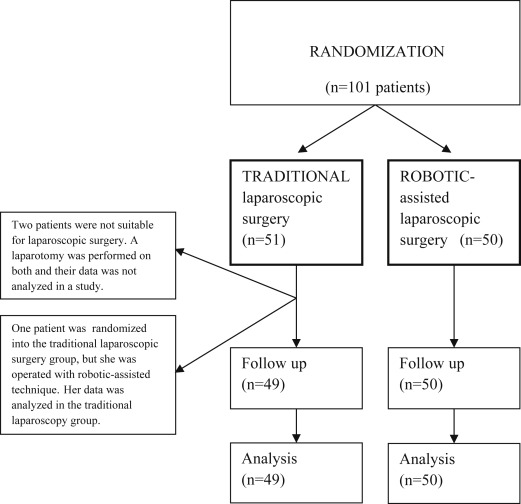

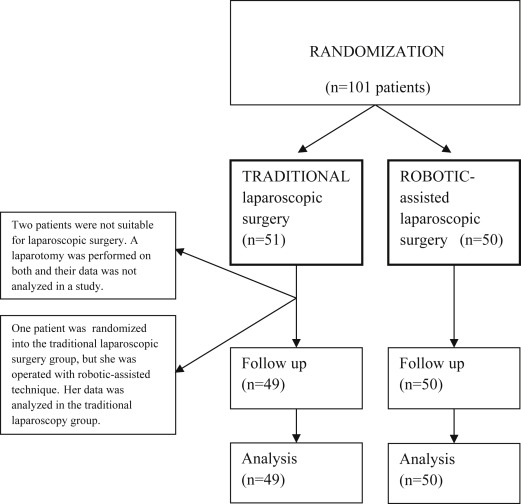

A total of 101 patients scheduled for laparoscopic hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO), and pelvic lymphadenectomy (PLND) at the Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics of Tampere University Hospital were randomized preoperatively to undergo either robotic-assisted (da Vinci S Surgical System; Intuitive Surgical Inc, Sunnyvale, CA) or conventional laparoscopic operation from December 2010 through October 2013 ( Figure 1 ). Only 1 patient refused to participate in the study.

Women eligible to the study had a low-grade (grade 1-2) endometrial carcinoma, and were scheduled for laparoscopic surgical staging, ie, for a laparoscopic hysterectomy along with BSO and PLND. The study exclusion criteria included a narrow vagina or a uterus too large to be removed through vagina, and the patient’s condition not allowing for a deep Trendelenburg position ( Figure 1 ). The operations were all performed by gynecologic oncologists with several years of experience with laparoscopic surgery. Thus, a learning curve was not included in the operations. The patients were randomized to undergo either traditional or robotic-assisted laparoscopic surgery, and were stratified for overweight (body mass index [BMI] <30 and ≥30) and age (<65 and ≥65 years). The randomization was made with the minimization software for allocating patients to treatments in clinical trials (MINIM, Version 1.5/28-3-90, by S. Evans, P. Royston, and S. Day [ https://www-users.york.ac.uk/∼mb55/guide/minim.htm ]).

The surgical techniques ( Table 1 ) differed between the groups in the insertion of trocars, entering the abdominal cavity, and closing the vagina. PLND was performed in the same way in both groups: The external iliac artery was skeletonized up to the bifurcation of the common iliac artery into the external and internal iliac arteries. The obturator lymph nodes were removed from the area between the obturator nerve and the external iliac vein. As antithrombotic prophylaxis, all patients were given low-molecular-weight-heparin and were wearing antithrombotic stockings. Cefuroxime was used as primary antibiotic prophylaxis, combined with metronidazole when indicated, and replaced with levofloxacin in case of cephalosporin allergy. A cytological sample from the pouch of Douglas was obtained from all patients.

| Traditional | Robot | |

|---|---|---|

| Entering abdominal cavity | Veress needle or open technique through umbilicus | Open technique |

| Size and placement of trocars | 10 mm for Camera in umbilicus, two 5 mm lateral to both epigastric arteries, 12 mm in midline above symphysis | 12 mm for Camera about 10 cm above umbilicus, two 8 mm in right and 8 mm in left upper and 12 mm in left lower abdomen |

| Uterine manipulator | Reusable | Disposable |

| Hysterectomy and BSO | Securing and dividing uterine vessels laparoscopically while ligating and dividing parametria vaginally | Uterus totally freed laparoscopically, and then removed via vagina |

| Closing vagina | Vaginal | Laparoscopic |

| Local cervical anesthesia | At onset of vaginal phase; levobupivacaine 0.5% 20 mL or lidocaine with adrenaline 0.25% 20 mL | At onset of operation; Chirocaine 0.5% 20 mL or lidocaine with adrenaline 0.25% 20 mL |

The operative specimens were otherwise processed and evaluated as part of the hospital routine practice, but an experienced gynecopathologist (M.L.) reviewed all lymph node samples. The relevant gynecologic and medical histories of the patients can be found in Table 2 . The patients’ hemoglobin level was measured preoperatively and postoperatively. By definition, a decrease in the hemoglobin level >40 g/L, and need of transfusion or estimated blood loss >500 mL were regarded as a bleeding complication. Early postoperative complications took place before discharge and late complications following discharge but during the next 6 months. Major infection required intravenous antibiotics and minor wound or urinary tract infection oral antibiotics.

| Traditional, n = 49 | Robot, n = 50 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y, median (range) | 70 (48–83) | 67 (43–84) | .298 |

| BMI, kg/m 2 , median (range) | 29 (20–45) | 29 (20–46) | .787 |

| Parity, n, median (range) | 2 (0–4) | 2 (0–9) | .971 |

| Preoperative hemoglobin, g/L, median (range) | 135 (88–160) | 136 (109–159) | .782 |

| Disease, n (%) | |||

| Cardiovascular | 27 (53) | 33 (66) | .181 |

| Pulmonary | 4 (8) | 6 (12) | .741 |

| Diabetes | 9 (18) | 4 (8) | .127 |

| Thromboembolic | 3 (6) | 3 (6) | 1.000 |

| Other | 20 (39) | 24 (49) | .373 |

| Existing antithrombotic medication, n (%) | 7 (14) | 7 (14) | .967 |

| Previous abdominal surgery, a n (%) | 28 (57) | 24 (48) | .362 |

a Majority of operations were laparotomies, 92% in both groups.

Written informed consent was obtained from the study participants. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tampere University Hospital (identification number ETL R10081). The trial was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov , www.clinicaltrials.gov , NCT01466777 .

Statistical plan

The primary outcome measure was overall operation time (skin to skin; time from the first incision to the last suture). The study was powered to show at least a 25% difference in operation time using 2-sided significance level of .05. For this, at least 45 patients were needed in each treatment arm to achieve a power of 0.80. The secondary outcome measures included the total time spent in the operating room, number of lymph nodes harvested, intraoperative complications and conversions, amount of bleeding, length of postoperative stay, and postoperative pain scale.

The differences between traditional laparoscopy and robotic surgery groups were tested by Pearson χ 2 test, Fisher exact test, or by Mann-Whitney and/or independent samples t test. The statistical analyses were performed using software (SPSS Statistics, Version 23; IBM Corp, Armonk, NY). P values <.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Materials and Methods

A total of 101 patients scheduled for laparoscopic hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO), and pelvic lymphadenectomy (PLND) at the Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics of Tampere University Hospital were randomized preoperatively to undergo either robotic-assisted (da Vinci S Surgical System; Intuitive Surgical Inc, Sunnyvale, CA) or conventional laparoscopic operation from December 2010 through October 2013 ( Figure 1 ). Only 1 patient refused to participate in the study.

Women eligible to the study had a low-grade (grade 1-2) endometrial carcinoma, and were scheduled for laparoscopic surgical staging, ie, for a laparoscopic hysterectomy along with BSO and PLND. The study exclusion criteria included a narrow vagina or a uterus too large to be removed through vagina, and the patient’s condition not allowing for a deep Trendelenburg position ( Figure 1 ). The operations were all performed by gynecologic oncologists with several years of experience with laparoscopic surgery. Thus, a learning curve was not included in the operations. The patients were randomized to undergo either traditional or robotic-assisted laparoscopic surgery, and were stratified for overweight (body mass index [BMI] <30 and ≥30) and age (<65 and ≥65 years). The randomization was made with the minimization software for allocating patients to treatments in clinical trials (MINIM, Version 1.5/28-3-90, by S. Evans, P. Royston, and S. Day [ https://www-users.york.ac.uk/∼mb55/guide/minim.htm ]).

The surgical techniques ( Table 1 ) differed between the groups in the insertion of trocars, entering the abdominal cavity, and closing the vagina. PLND was performed in the same way in both groups: The external iliac artery was skeletonized up to the bifurcation of the common iliac artery into the external and internal iliac arteries. The obturator lymph nodes were removed from the area between the obturator nerve and the external iliac vein. As antithrombotic prophylaxis, all patients were given low-molecular-weight-heparin and were wearing antithrombotic stockings. Cefuroxime was used as primary antibiotic prophylaxis, combined with metronidazole when indicated, and replaced with levofloxacin in case of cephalosporin allergy. A cytological sample from the pouch of Douglas was obtained from all patients.

| Traditional | Robot | |

|---|---|---|

| Entering abdominal cavity | Veress needle or open technique through umbilicus | Open technique |

| Size and placement of trocars | 10 mm for Camera in umbilicus, two 5 mm lateral to both epigastric arteries, 12 mm in midline above symphysis | 12 mm for Camera about 10 cm above umbilicus, two 8 mm in right and 8 mm in left upper and 12 mm in left lower abdomen |

| Uterine manipulator | Reusable | Disposable |

| Hysterectomy and BSO | Securing and dividing uterine vessels laparoscopically while ligating and dividing parametria vaginally | Uterus totally freed laparoscopically, and then removed via vagina |

| Closing vagina | Vaginal | Laparoscopic |

| Local cervical anesthesia | At onset of vaginal phase; levobupivacaine 0.5% 20 mL or lidocaine with adrenaline 0.25% 20 mL | At onset of operation; Chirocaine 0.5% 20 mL or lidocaine with adrenaline 0.25% 20 mL |

The operative specimens were otherwise processed and evaluated as part of the hospital routine practice, but an experienced gynecopathologist (M.L.) reviewed all lymph node samples. The relevant gynecologic and medical histories of the patients can be found in Table 2 . The patients’ hemoglobin level was measured preoperatively and postoperatively. By definition, a decrease in the hemoglobin level >40 g/L, and need of transfusion or estimated blood loss >500 mL were regarded as a bleeding complication. Early postoperative complications took place before discharge and late complications following discharge but during the next 6 months. Major infection required intravenous antibiotics and minor wound or urinary tract infection oral antibiotics.