Fig. 11.1

Representative anatomy of the mid urethra in a coronal plane (Used with permission from Rovner ES. Urethral diverticula. In: Female Urology, 3rd ed. Edited by Raz S, Rodriguez LV. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2008)

Fig. 11.2

Diagram of urethral diverticulum. The urethral diverticulum forms within and between the layers of the urethropelvic ligament (Used with permission from Rovner ES. Urethral diverticula. In: Female Urology, 3rd ed. Edited by Raz S, Rodriguez LV. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2008)

The periurethral glands are the probable site of origin of acquired UD [1]. Huffman characterized the periurethral glands as being located mostly dorsolateral to the urethra, arborizing proximally along the urethra, but also draining into ducts located in the distal one-third of the urethra [4]. Importantly, he noted that periductal and interductal inflammation was also commonly found. In support of his observations and an infectious or acquired etiology of UD, in over 90 % of cases, the ostia is located posterolaterally in the mid to distal urethra which corresponds anatomically to the location of the periurethral glands [5, 6].

Peters and Vaughn found that there was a strong association with concurrent or previous infection with Neisseria gonorrhea and UD [7]. However, the initial infection and subsequent reinfections might also originate from a variety of sources including E. coli, and other coliform bacteria, as well as flora within the vagina. Nevertheless, UD have been classically attributed to recurrent infection of the periurethral glands with obstruction, suburethral abscess formation and consequent rupture of these infected glands into the urethral lumen. Continual filling and collection of urine in the resultant cavity may result in stasis, recurrent infection, and possible eventual epithelialization of the cavity forming a permanent diverticulum [8]. Reinfection, inflammation, and recurrent obstruction of the neck of the cavity are hypothesized to result in patient symptoms and enlargement of the diverticulum. However, it should be noted that Daneshgari and colleagues have also reported noncommunicating urethral diverticula diagnosed by MRI [9].

Diverticular Anatomy

Typically, UD represent an epithelialized cavity with a single connection to the lumen of the urethra. The size of the lesion may vary from just a few millimeters to several centimeters. In addition, the size may vary over time due to inflammation, intermittent obstruction of the ostia, and subsequent drainage into the urethral lumen.

The epithelium of UD may consist of columnar, cuboidal, stratified squamous, or transitional cells. In some cases, the epithelium is absent and the wall of the UD consists only of fibrous tissue. These lesions are found within the periurethral fascia, bordered by the anterior wall of the vagina ventrally. In the sagittal plane, UD are most often centered in the middle third of the urethra with the luminal connection or ostia located posterolaterally. The sac may extend distally along the urethra and vaginal wall, almost to the meatus or proximally to the level of the bladder neck, underneath the trigone of the bladder. An array of configurations can be noted on imaging and at surgical exploration. In the axial plane, the UD cavity may extend laterally along the urethral wall and in some cases around the dorsal side of the urethra or wrap circumferentially around the entire urethra. UD may be bilobed (dumbbell shaped) extending across the midline. Multiple loculations can be common, and at least 10 % of patients have multiple UD at presentation. Varying degrees of sphincteric compromise may exist due to the location of diverticulum relative to the proximal and distal urethral sphincter mechanisms. This is especially important to note when considering surgical repair.

Evaluation/Work-Up

The diagnosis and complete evaluation of UD can be made with a combination of a thorough history, physical exam, urine culture and analysis, cystourethroscopy, and selected imaging studies. A urodynamic evaluation may also be utilized in select cases.

Presentation

Most patients with UD present between the 3rd and 7th decades of life [10–14]. The classic presentation has been historically described as the “three Ds”: dysuria, dyspareunia, and dribbling (post-void). However, none of these symptoms are sensitive or specific for UD. Although presentation is quite variable, the most common symptoms are irritative (frequency, urgency, etc.) lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS), pain, and infection [7, 15–17]. Dyspareunia will be noted by 12–24 % of patients [15, 16]. Approximately 5–32 % of patients complain of post-void dribbling [11, 15]. Recurrent cystitis or urinary tract infection is also a frequent presentation in one-third of subjects [11, 15] likely due to stasis of urine in the UD. Multiple bouts of recurrent cystitis should alert the physician to the possibility of a UD. Other complaints include vaginal pain or mass, hematuria, vaginal discharge, obstructive symptoms, urinary retention, and incontinence (stress or urge). Up to 20 % of patients diagnosed with UD might be completely asymptomatic. Some patients may present with a tender or non-tender anterior vaginal wall mass, which upon gentle compression may reveal retained urine or purulent discharge per the urethral meatus. Although spontaneous rupture of UD is extremely rare, urethrovaginal fistula may result under these circumstances [18].

The size of the diverticulum does not correlate with symptoms. Finally, symptoms may wax and wane, and even resolve for long periods of time. This may be related to periodic and repeated episodes of infection and inflammation.

As many symptoms associated with UD are not specific, patients often can be misdiagnosed and treated for years before the diagnosis of UD is made. In one series of 46 consecutive women eventually diagnosed with UD, the mean interval from onset of symptoms to diagnosis was 5.2 years [19]. This underscores the importance of a baseline level of suspicion and a thorough pelvic exam in patients complaining of LUTS or other symptoms potentially associated with UD.

Physical Examination

During physical examination, the anterior vaginal wall should be palpated for masses and tenderness. The location, size, and consistency of a suspected UD should be noted. Most UD are located ventrally over the middle and proximal portions of the urethra, corresponding to the area of the anterior vaginal wall 1–3 cm inside the introitus (Fig. 11.3). Configuration of the UD may have significant implications when undertaking surgical excision and reconstruction. UD may also extend proximally towards the bladder neck. Such UD may produce distortion of the bladder outlet and trigone on cystoscopy or on radiographic imaging and special care should be taken during surgical excision and reconstruction due to concerns for bladder and ureteral injury as well as the potential development of postoperative voiding dysfunction and incontinence. Distal vaginal masses or perimeatal masses may represent other lesions, including Skene’s glands abnormalities. The differentiation between these lesions often cannot be made by physical examination alone, and may require additional radiological imaging. A particularly hard anterior vaginal wall mass may indicate a calculus, vaginal wall fibroid, or cancer within the UD and mandates further investigation. During physical exam, the urethra may be gently “stripped” or “milked” distally in an attempt to express purulent material or urine from within the UD cavity. Although often described for the evaluation of UD, this maneuver does not produce the diagnostic discharge per urethral meatus in the majority of patients [20].

Fig. 11.3

Intraoperative image of a large urethral diverticulum

Vaginal walls should be assessed for atrophy, rugation, and elasticity. Poorly estrogenized, atrophic tissues are important to note if surgery is being considered. These tissues are often surgically mobilized and may be used for flaps during excision and reconstruction. The distal vagina and vaginal introitus are also assessed for capacity. These factors may impact surgical planning, as a narrow introitus can make surgical exposure difficult and may mandate an episiotomy. Finally, during physical examination, a provocative maneuver to elicit stress incontinence should be performed as well as an assessment of any vaginal prolapse.

Urine Studies

Urinalysis and urine culture should be performed. The most common organism isolated in patients with UD is E. coli. However, other gram negative enteric flora as well as N. gonorrhea, Chlamydia, Streptococcus, and Staphylococcus are often present [16, 21]. A sterile urine culture does not exclude infection, as these patients are often on antibiotic therapy at presentation. In patients with irritative symptoms or where there is suspicion of malignancy, a urine cytology can be checked.

Cystourethroscopy

Cystourethroscopy is performed, both in an attempt to visualize the UD ostia, as well as to evaluate for other potential causes of the patient’s LUTS. A flexible cystoscope or a specially designed rigid female cystoscope is most helpful in evaluating the female urethra. The short beak maintains the flow of the irrigation solution immediately adjacent to the lens and thus aids in distention of the relatively short (as compared to the male) urethra, permitting improved visualization. It may also be advantageous to compress the bladder neck while simultaneously applying pressure to the diverticular sac with an assistant’s finger. Luminal discharge of purulent material can often be seen with this maneuver or with digital compression of the UD during urethroscopy. Again, the UD ostia is most often located posterolaterally at the level of the midurethra, but can be very difficult to identify in some patients. The success in identifying a diverticular ostia on cystourethroscopy is quite variable, and reported to be between 15 % and 89 % [11, 15, 20]. Failure to visualize an ostia on cystourethroscopy should not influence the decision to proceed with further investigations or surgical repair.

Urodynamics

For patients with UD and urinary incontinence or significant voiding dysfunction, a urodynamic study may be helpful [22–24]. Urodynamics can document the presence or absence of stress urinary incontinence prior to repair. Approximately 50 % of women with UD will demonstrate SUI on urodynamic evaluation [11, 25]. A videourodynamic study combines both a voiding cystourethrogram and a urodynamic study, thus consolidating the diagnostic evaluation and decreasing the number of required urethral catheterizations during the patient’s work-up. For patients undergoing surgery for UD with coexistent bothersome stress urinary incontinence demonstrated on physical examination, or urodynamically demonstrable SUI, or those found to have an open bladder neck on preoperative evaluation, a concomitant anti-incontinence surgery can be offered. Multiple authors have described successful concomitant repair of urethral diverticula and stress incontinence in the same operative setting [11, 25–27]. Alternatively, on urodynamic evaluation, a small number of patients may have evidence of bladder outlet obstruction due to the obstructive or mass effects of the UD on the urethra. It should be noted that SUI may coexist with obstruction [28, 29] but nevertheless, both conditions can be treated successfully with a carefully planned operation.

Imaging

A number of imaging techniques have been applied to the study of female UD. Currently available techniques for the evaluation of UD include double-balloon positive-pressure urethrography (PPU), voiding cystourethrography (VCUG) (Fig. 11.4), intravenous urography (IVU), ultrasound (US), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Fig. 11.5), with or without an endoluminal coil (eMRI). MRI has become the imaging modality of choice in many centers due to its relatively noninvasive nature, and ability to visualize the anatomy in multiple planes [30–32].

Fig. 11.4

A voiding cystourethrogram demonstrates a urethral diverticulum (Used with permission from Rovner ES. Urethral diverticula. In: Female Urology, 3rd ed. Edited by Raz S, Rodriguez LV. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2008)

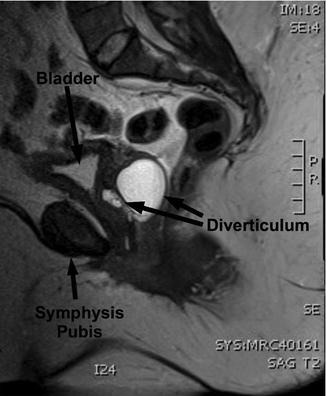

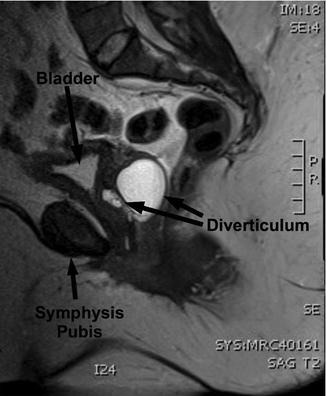

Fig. 11.5

Sagittal MRI demonstrating a urethral diverticulum

Surgical Repair

Indications for Repair

Although often highly symptomatic, not all urethral diverticula mandate surgery. Some patients may be asymptomatic at presentation, with the lesion diagnosed incidentally. Whether these lesions will progress in size, symptoms or complexity over time is not known. For these reasons, and due to the lack of symptoms in selected cases, some patients may not desire surgical therapy. However, it should be noted that there are multiple reports in the literature of carcinomas arising in UD [29, 33–40] which may be asymptomatic and may not be prospectively identified on radiologic imaging [41].

Symptomatic patients, including those with dysuria, refractory bothersome post-void dribbling, recurrent UTIs, dyspareunia and pelvic pain, may be offered surgical excision. Those with UD and symptomatic bothersome stress urinary incontinence can be considered for a concomitant anti-incontinence procedure at the time of UD excision.

Techniques for Repair

Alternative Techniques

A variety of surgical interventions for urethral diverticula have been reported since 1805 when Hey described transvaginal incision of the UD and packing of the resulting cavity with lint [1]. Approaches have included transurethral and open [42, 43] marsupialization, endoscopic unroofing [44, 45], fulguration [46], incision and obliteration with oxidized cellulose [47] or polytetrafluoroethylene [48], coagulation, and excision with reconstruction. Most commonly, a complete excision and reconstruction is performed. However, for distal lesions, a transvaginal marsupialization as described by Spence and Duckett may reduce operative time, blood loss and recurrence rates [42, 43, 49]. During this procedure, care must be taken to avoid aggressively extending the incision proximally which could result in vaginal voiding or potentially damage the proximal and distal sphincteric mechanism, resulting in postoperative stress incontinence. Therefore, this approach is probably only applicable to UD in very select cases involving the distal one-third of the urethra, and as such, it is not commonly performed.

Excision and Reconstruction

Excision with reconstruction is the most common surgical approach to UD in the modern era. The principles of the urethral diverticulectomy operation have been well described. There are only a few minor issues about which some surgeons may disagree including the type of vaginal incision (inverted “U” vs. inverted “T”), whether it is necessary to remove the entire mucosalized portion of the lesion, and finally, the optimal type of postoperative catheter drainage (urethra only versus urethra and suprapubic).

Complex urethral reconstructive techniques for the repair of UD have been described. Fall described the use of a bipedicled vaginal wall flap for urethral reconstruction in patients with UD and urethrovaginal fistula [50]. Laterally based vaginal flaps have also been utilized as an initial approach to UD [51, 52]. Complex anatomical configurations may exist and many novel approaches have been described for complicated anterior or circumferential lesions [2, 3, 53]. The technique described herein is similar to that described by Leach and Raz [17] based on earlier work by Benjamin et al. [54] and Busch and Carter [55].

Preoperative Preparation

Prophylactic antibiotics can be utilized preoperatively to ensure sterile urine at the time of surgery. Patients can also be encouraged to strip the anterior vaginal wall following voiding, thereby consistently emptying the UD and preventing urinary stasis and recurrent UTIs. This may not be possible in those with noncommunicating UD or in those who have significant pain related to the UD. Application of topical estrogen creams for several weeks prior to surgery may be beneficial in some patients with postmenopausal atrophic vaginitis in improving the quality of the tissues with respect to dissection and mobilization. Preoperative parenteral antibiotics are often administered, especially for those with recurrent or persistent UTIs.

Patients with symptomatic stress urinary incontinence can be offered simultaneous anti-incontinence surgery. Preoperative videourodynamics may be helpful in evaluating the anatomy of the UD, assessing the competence of the bladder neck, and confirming the diagnosis of stress incontinence. In patients with SUI and UD, Ganabathi and others have described excellent results with concomitant needle bladder neck suspension in these complex patients [11, 56]. More recently, pubovaginal fascial slings have been utilized in patients with UD and stress urinary incontinence with satisfactory outcomes [19, 26, 27]. According to the AUA Stress Urinary Incontinence Guidelines, synthetic slings should not be used synchronously at the time of the surgical repair of UD [57]. There may be an increased risk of sling erosion in such circumstances.

Further complicating these cases may be associated pain, dyspareunia, voiding dysfunction, urinary tract infections, and urinary incontinence. These associated symptoms are often, but not always improved or eliminated with surgery. Therefore, the importance of appropriate preoperative patient counseling regarding surgical repair and postoperative expectations of cure cannot be overemphasized.

Procedure

The patient is placed in the lithotomy position with all pressure points well padded. The use of padded adjustable stirrups for the lower extremities greatly enhances operative access to the perineum. A standard vaginal antiseptic preparation is applied. A weighted vaginal speculum and Scott retractor with hooks aid in exposure. A posterolateral episiotomy may be beneficial in some patients for additional exposure although the midurethral (and therefore somewhat distal in the vaginal canal) location of most UD usually preclude the need for this. A Foley catheter is placed per urethra and a suprapubic tube may be utilized for additional postoperative urinary drainage. Often, a small caliber urethral catheter is utilized during the case and the placement of a suprapubic tube during the procedure ensures maximal postoperative urinary drainage. If desired, a suprapubic tube is placed at the start of the procedure either using the Lowsley retractor or percutaneously under direct transurethral cystoscopic visual guidance. Placement of a suprapubic tube at the end of the case is not advisable, as this will require traversing the fresh urethral suture line and risk disruption of the repair.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree