Renal Masses and Urinary Ascites

RENAL MASSES

Abdominal masses are frequent in the neonate, and nearly two-thirds are renal in origin. Most are benign, representing hydronephrosis, multicystic dysplastic kidney (MCDK), polycystic kidney disease, or congenital mesoblastic nephroma. Less commonly, a flank mass may be caused by a malignant renal lesion, such as a Wilms tumor. The initial diagnosis may be made on prenatal ultrasonography (US), found in an asymptomatic infant on physical palpation, or discovered as a consequence of postnatal imaging performed for hypertension, hematuria, urinary sepsis, or difficult feeding in the new infant.1 Fetal ultrasonography may demonstrate not only the renal mass but also associated findings, such as oligohydramnios, polyhydramnios, renal cysts, hydronephrosis, and bladder wall thickness, which may aid in developing a more specific diagnosis in the antenatal period.2 Early recognition of renal masses may allow timely treatment of congenital renal anomalies that would otherwise be missed because of their asymptomatic nature.

The postnatal examination will be the first opportunity to palpate an abdominal mass and evaluate for any associated genitourinary or systemic anomalies. Examination of the external genitalia and lumbosacral region is imperative because malformations of these organ systems are increased in the setting of renal and urinary anomalies. A postnatal abdominal US should be performed to confirm the renal origin of the mass, define whether it is solid or cystic, and better delineate the collecting system anatomy. More specific postnatal imaging, such as voiding cystourethrogram (VCUG), nuclear medicine renal scans, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) will be guided by the suspected diagnosis.

Cystic Masses

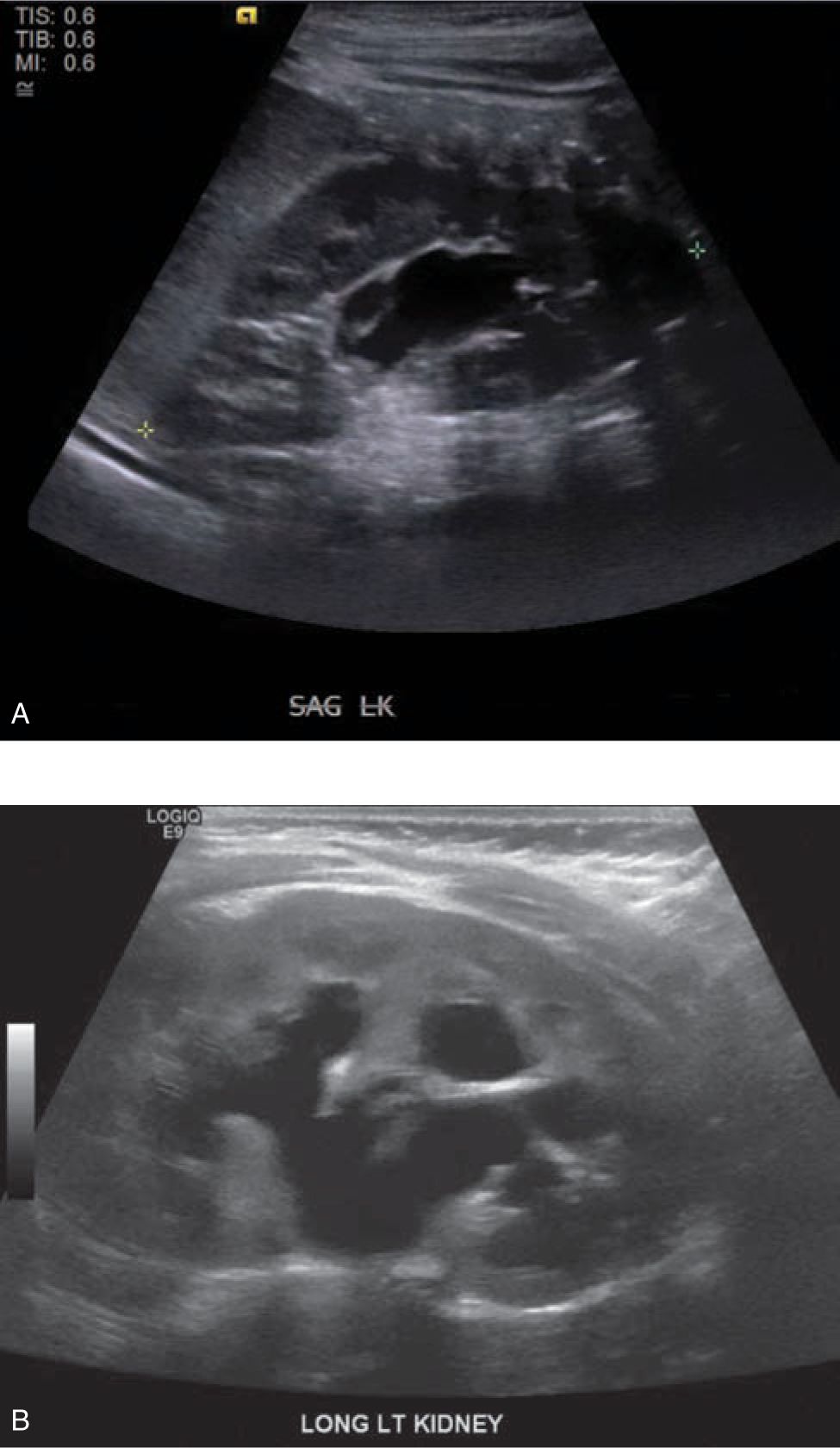

Cystic masses of the neonate may include hydronephrosis, MCDK, and autosomal dominant and autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease. The most common cause of a renal mass in the newborn is hydronephrosis. This may be caused by ureteropelvic junction (UPJ) obstruction, primary megaureter, vesicoureteral reflux (VUR), ureterovesical junction obstruction, or bladder outlet obstruction. Follow-up imaging with repeat renal bladder US and a VCUG should be performed to delineate the etiology of the hydronephrosis. The recommended timing of the first postnatal US has been a controversial subject. It has been posited that an US performed within the initial 24-48 hours of life may underestimate the degree of hydronephrosis because of relative dehydration3 (Figure 100-1).

FIGURE 100-1 A, Newborn with left antenatal hydrone phrosis imaged with ultrasound on day one of life with minimal hydronephrosis (Society for Fetal Urology Grade 1). B, Same newborn with left antenatal hydronephrosis imaged with ultrasound at one week of life with moderate hydronephrosis (Society for Fetal Urology Grade 3).

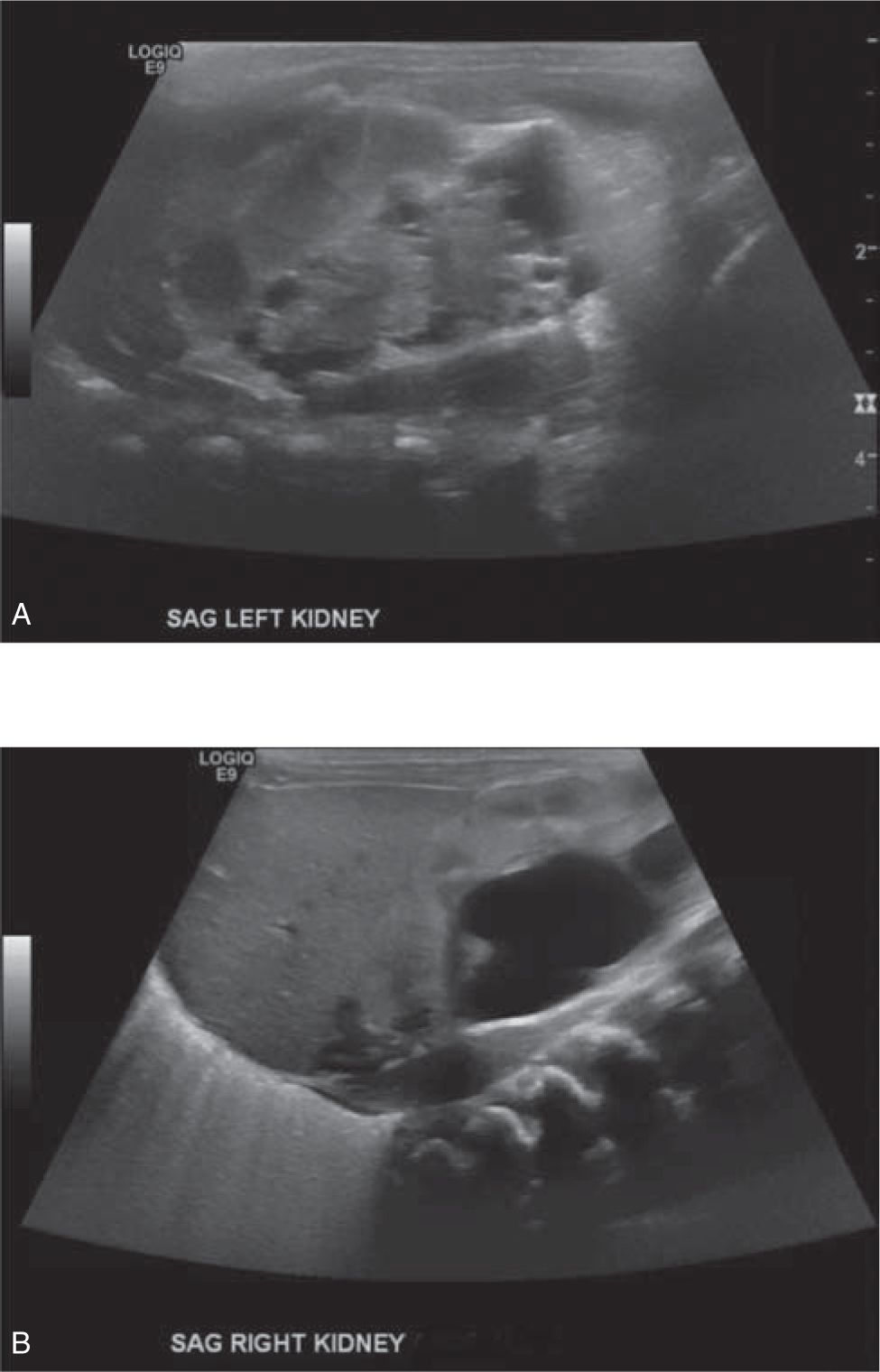

Multicystic dysplastic kidney is the second-most-common cause for a cystic renal mass in the newborn. More than 50% of cases are detected antenatally. It is typically a unilateral cystic renal mass, more commonly found in male infants, and is characterized sonographically by numerous noncommunicating cysts separated by dysplastic renal tissue. The contralateral kidney may show compensatory hypertrophy or may be associated with other defects, such as rotation anomalies, VUR, ureteroceles or UPJ obstruction. The prognosis is favorable in cases of solitary, unilateral MCDK, whose natural history without intervention is typically involution of the affected kidney. Chronic renal insufficiency has been seen in up to 50% of cases if there is contralateral genitourinary involvement; therefore, long-term follow-up by a pediatric urologist is mandatory to monitor renal function4 (Figure 100-2).

FIGURE 100-2 A, Newborn with left multicystic dysplastic kidney (MCDK) imaged with ultrasound at birth. B, Contralateral right kidney in the same newborn has moderate hydronephrosis which progressed ultimately requiring pyeloplasty for a ureteropelvic junction obstruction.

Two forms of hereditary cystic disease may be diagnosed in the setting of an imaged or palpated renal mass in the perinatal and neonatal period. Autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease (ARPKD), previously called infantile polycystic kidney disease, is a recessively inherited disorder characterized by dilation of the distal tubules and collecting ducts. There is a spectrum of presentation of this condition. Infants are more likely to present with a history of oligohydramnios, Potter facies, massively enlarged kidneys, pulmonary hypoplasia, and rapid progression to end-stage renal disease.5 Patients who present later in life more commonly display features of hepatic disease, including hepatosplenomegaly, hypersplenism, variceal bleeding, cholangitis, and less-severe renal involvement. ARPKD can be diagnosed after 24 weeks of gestation by fetal US demonstrating markedly enlarged kidneys with increased echogenicity and loss of corticomedullary differentiation, often without discretely visible cysts. Infants may have marked abdominal distention from bilateral renal involvement on physical examination. Molecular genetic testing is only used in the setting of an uncertain diagnosis or during prenatal diagnosis and counseling.

Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease, or adult polycystic kidney disease, has been increasingly diagnosed in neonates and children. It is characterized by cystic dilations in all parts of the nephron. The kidneys are distended with large radiographically detectable cysts. The diagnosis is most commonly made in the pediatric population on the basis of a renal US performed in the setting of a positive family history. It is distinct from the recessive form of the disease in that hepatic, pancreatic, and splenic involvement is rarely observed in childhood, and renal insufficiency does not typically develop until adulthood.6 Management of these two diseases is largely supportive, with attention to long-term follow-up of renal function.

Solid Renal Masses

Solid renal masses may result from benign causes such as renal vein thrombosis and congenital mesoblastic nephroma or be caused by malignant conditions such as Wilms tumor.

Renal vein thrombosis (RVT) may be suspected in the ill neonate with a classic triad of microscopic or macroscopic hematuria, a palpable flank mass, and thrombocytopenia. It accounts for 10% of cases of venous thrombosis in newborns and is the leading cause of non-catheter-associated venous thrombosis. Risk factors include perinatal asphyxia, maternal diabetes mellitus, prematurity, dehydration, and infection.7 Sonographic features are notable for diffuse renal enlargement, diffusely or focally increased echogenicity, and perivascular echogenic streaking, with abnormal Doppler flow caused by intravenous thrombus.8 Treatment is largely supportive care, correction of the underlying etiology, and anticoagulation therapy depending on the extent of the thrombus.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree