Rapid-Onset Obesity with Hypothalamic Dysfunction, Hypoventilation, and Autonomic Dysregulation (ROHHAD)

Epidemiology and History

The first case of rapid-onset obesity with hypothalamic dysfunction, hypoventilation, and autonomic dysregulation (ROHHAD) was described in 19651 as a 3.5-year-old boy who developed signs of hypoventilation within 9 months of onset of rapid weight gain. The hypoventilation did not improve with weight loss, suggesting a distinction from Pickwickian syndrome (now known as obesity hypoventilation syndrome). Furthermore, this child developed a transient central diabetes insipidus indicating hypothalamic dysfunction. Accordingly, the case was described as the first patient with alveolar hypoventilation and hypothalamic disease. It was not until 2000 that the possibility of a distinct syndrome was evoked and called late-onset central hypoventilation syndrome with hypothalamic dysfunction (LO-CHS/HD)2 with description of a new case and review of the 10 existing cases in the literature.

Although children with ROHHAD can present with obstructive sleep apnea after development of obesity, the condition is markedly distinct from obstructive sleep apnea hypoventilation syndrome3 and obesity hypoventilation syndrome in which chronic obstructive sleep apnea with resulting overnight hypercarbia, hypoxemia, and frequent arousals leads to daytime awake hypoventilation, hypoxemia, and daytime sleepiness. The management of these disorders involves relief of the obstruction, which would be expected to resolve the hypoventilation and daytime sleepiness completely. In contrast, relief of the upper airway obstruction in ROHHAD children often unveils the presence of the underlying primary central alveolar hypoventilation.

Congenital central hypoventilation syndrome (CCHS) is a disorder of the autonomic nervous system (ANS) that is similar to ROHHAD such that respiratory control and ANS dysregulation (ANSD) are key features.4 In contrast to ROHHAD, CCHS is often diagnosed in the newborn period, but milder cases of CCHS can go undiagnosed even until adulthood. These later-presenting cases of CCHS can potentially lead to some confusion in distinguishing cases of ROHHAD from CCHS. However, within the past decade a genetic basis was identified for CCHS, allowing rapid, objective diagnosis of CCHS, providing a definitive distinction from cases of ROHHAD.

In 2007, a cohort of 23 ROHHAD cases was described and found not to have congenital central hypoventilation syndrome (CCHS)-associated PHOX2B mutations.5 With intention to facilitate early diagnosis, the acronym ROHHAD was created at this time. Specifically, the rapid weight gain was most often the presenting sign. In 2008, a new acronym, ROHHADNET, was introduced because of the finding of neural crest tumors.6 These authors described six cases, all with ganglioneuromas. The difficulty with this acronym is that only a subset of patients (33–40%)5,7 with ROHHAD will develop these tumors, which may lead to missed diagnosis. Despite the confusion due to multiple names/acronyms for the same disorder and the high occurrence of cardiorespiratory arrest (50–60%),5,6,8 there has been a dramatic increase in reported cases since 2007. Currently, it is estimated that there are at least 100 children worldwide affected by ROHHAD. It is not yet clear whether any particular population is at greater risk for developing ROHHAD.

Diagnosis and Presentation

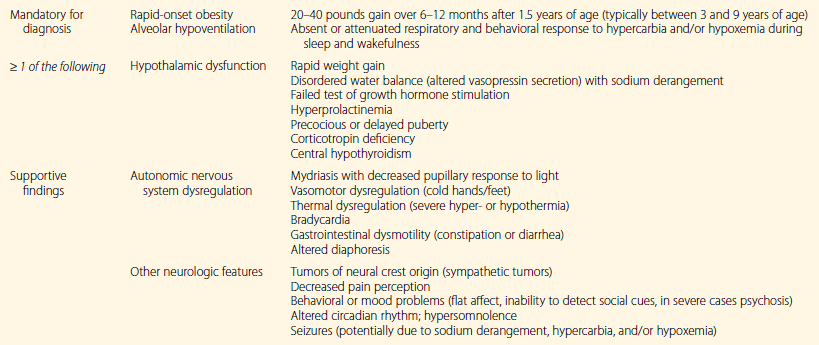

The diagnosis of ROHHAD is currently based on clinical criteria (Table 38.1): (1) rapid-onset obesity and alveolar hypoventilation starting after the age of 1.5 years, (2) evidence of hypothalamic dysfunction, as defined by ≥1 of the following findings: rapid-onset obesity, hyperprolactinemia, central hypothyroidism, disordered water balance, failed growth hormone stimulation test, corticotropin deficiency, or altered onset of puberty (delayed or precocious), and (3) absence of PHOX2B mutation (to genetically distinguish ROHHAD from CCHS). Since a single diagnostic test is not yet available for ROHHAD, it is essential to be attentive to the clinical presentation and course, which should include cooperative consultation by experts in the fields of respiratory, endocrine, and autonomic medicine.

One of the most remarkable features of ROHHAD is that affected children appear to be completely normal prior to the onset of symptoms. Most often, the first sign is a dramatic, unexplained weight gain,5 which occurs anywhere between 1.5 to 7 years of age. With variable timing, the affected child will then develop further signs of hypothalamic dysfunction. Evidence of hypothalamic dysfunction can potentially be found with laboratory investigation guided by a pediatric endocrinologist. Hypoventilation can also be found soon after presentation of rapid-onset obesity or even years later.5 Presentation of hypoventilation can include episodes of hypoxemia during sleep, cyanosis while awake (without associated respiratory distress), and most often cardiorespiratory arrest. Features of ANSD may occur early or late in the course, as there appears to be wide variation in age at onset, but tend to be less threatening and more difficult to identify due to limited availability of objective measures of ANSD for use in children.

Comprehensive Evaluation and Management

Since ROHHAD affects multiple systems, successful management involves coordinated multidisciplinary care primarily involving the pediatrician, sleep medicine physician, pulmonologist, and endocrinologist. Over the course of the disease, multiple other subspecialists may be actively involved and can include cardiologists, intensivists, otolaryngologists, surgeons, gastroenterologists, neurologists, ophthalmologists, psychologists, and psychiatrists.9 As there is no cure for ROHHAD, key to management are close monitoring and symptomatic treatment based on the affected systems.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree