Protecting the Health Professional Against Hazardous Exposures

Jason Y. Kim

Louis M. Bell

Introduction

Health care workers (HCWs) practice medicine in a potentially dangerous environment. Occupational health hazards include infectious, chemical, and radioactive exposures. The high volume, high acuity, and unscheduled nature of emergency medicine practice make emergency health professionals unique in their potential for such exposures. This is particularly important in the practice of pediatric emergency medicine, where infectious disease and accidental poisoning are commonly encountered. HCWs need to be aware of and continually educated about their risks from hazardous exposures. This chapter provides an overview of the risks associated with occupational exposure to infectious, chemical, and radioactive agents. Guidelines for exposure prevention and control are discussed.

Infectious Disease Exposures

Microbiologic Considerations

HCWs are at risk of acquiring many different infectious diseases, which can be transmitted via blood, respiratory secretions, and other body fluids. Routes of exposure to infectious agents include percutaneous inoculation of and contact with nonintact skin or mucous membranes by contaminated blood or body fluids. More than 20 different infectious diseases can be transmitted via blood-contaminated or body fluid–contaminated needles. Of particular importance among these agents are human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), and hepatitis B virus (HBV). Exposure by aerosol droplets from the respiratory tract of infected patients and direct contact with infected secretions can place the HCW at risk of acquiring many serious infections. These include tuberculosis, measles, varicella, pertussis, cytomegalovirus, meningococcus, pneumococcus, and adenovirus infections.

Indications

The care of pediatric emergency department patients is highly procedure oriented. Medical and trauma resuscitations are particularly high-risk situations that place the HCW in close contact with blood and other body fluid secretions. Close patient contact makes occupational exposure to infectious diseases common for emergency medicine HCWs in their everyday practice. This is particularly true for pediatric emergency medicine HCWs because children do not routinely have good hygienic practices and, in comparison to adults, have an increased incidence of infections. Precautions to limit HCW exposure and prevent occupational acquisition of infectious diseases are indicated in virtually every emergency department (ED) encounter and rest on two fundamental principles: most infectious diseases are contagious before the patient and HCW are aware of the diagnosis, and following infection control guidelines will help prevent transmission.

Procedures

Guidelines for Infection Control

Hospital employee health services should provide annual or biannual screening for each HCW, including Mantoux skin

testing for tuberculosis, annual influenza vaccination, and, for those regularly exposed to blood, vaccination against HBV if the HCW is without HBV immunity. In addition, the HCW’s immunity to varicella, rubella, measles, mumps, pertussis, and polio, either by history of disease or by immunization, should be documented. If protective immunity is lacking, the appropriate vaccine should be administered. For infections that are not preventable by vaccination, such as adenovirus conjunctivitis, the HCW should be counseled about the risks of exposure. Some infections pose increased risk for pregnant HCWs, and these are discussed later in this chapter.

testing for tuberculosis, annual influenza vaccination, and, for those regularly exposed to blood, vaccination against HBV if the HCW is without HBV immunity. In addition, the HCW’s immunity to varicella, rubella, measles, mumps, pertussis, and polio, either by history of disease or by immunization, should be documented. If protective immunity is lacking, the appropriate vaccine should be administered. For infections that are not preventable by vaccination, such as adenovirus conjunctivitis, the HCW should be counseled about the risks of exposure. Some infections pose increased risk for pregnant HCWs, and these are discussed later in this chapter.

Needlestick Injuries

There are approximately 384,000 needlestick injuries per year among all HCWs, and about 60% are associated with hollow-bore needles. (1). Despite a 6% to 30% risk of infection with HBV to a hepatitis B surface antibody-negative HCW following a needlestick exposure from a hepatitis B surface antigen-positive patient, HCWs paid little attention to needlestick injuries in the ED before the HIV-AIDS epidemic. In the current era, acquisition of HIV by needlestick injury is associated with significant morbidity, from either HIV infection itself or from antiretroviral therapy. Percutaneous exposure to the blood of an HIV-infected patient places the HCW at an approximate 0.3% risk of acquiring HIV infection (2,3). Nonparenteral (mucous membrane and nonintact skin) exposure to the blood of an HIV-infected patient is associated with a decreased rate of acquisition. The risk of acquisition following percutaneous exposure to certain other body fluids of an HIV-infected patient is unknown. The likelihood of a HCW becoming infected at work with HIV or other bloodborne pathogens depends on the rate of parenteral or nonparenteral exposure to the blood of an infected patient and the local prevalence of the infection. As of 2001, 57 HCWs have been reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDCP) with HIV seroconversion following an occupational exposure, and 88% of the cases were the result of percutaneous needlestick injury (4). Mucous membrane and skin exposure to blood is a commonplace event in the practice of pediatric emergency medicine (5). Virtually all hospital-related blood contacts involve the hand (5,6). Needlestick injury is less common but does occur. As the prevalence of HIV infection continues to rise, so does the rate at which recognized and unrecognized HIV-infected patients present for emergency care. Several reports from inner-city and non-inner-city EDs have focused attention on the high prevalence rates of HIV infection in adult patients (7,8,9,10,11,12,13). Published data on the prevalence rate of HIV among children presenting to the ED are limited (14). With continued adolescent participation in high-risk behaviors and increased survival of vertically infected infants, HIV-infected patients presenting to pediatric EDs are likely to increase in number and not be restricted to inner-city EDs.

Universal Precautions

Recognizing the risks of occupational exposure to HIV and other bloodborne pathogens in health care settings, in 1985 the CDCP published recommendations for preventing HIV transmission in the workplace (15). The CDCP referred to this approach as “universal blood and body fluid precautions” or “universal precautions.” The CDCP has subsequently consolidated and updated its recommendations (16,17,18,19).

Universal precautions are essentially barrier precautions based on infection control principles designed to prevent parenteral, nonintact skin, and mucous membrane exposures to bloodborne pathogens (20). The tenets include routine use of gloves, masks, protective eyewear, and impervious gowns and ways of preventing injuries when handling needles and sharp instruments. Table 8.1 reviews infection control requirements for exposure to body fluids and procedures performed in the ED.

Universal precautions are currently our best strategy for preventing occupational exposure to blood and body fluids. While postexposure prophylaxis regimens have demonstrated efficacy in reducing the risk of transmission of HIV, their efficacy is not absolute.

Gloves should be worn during all vascular access procedures (e.g., phlebotomy, arterial blood sampling, and intravenous line placement), during examinations of nonintact skin and mucous membranes, and when touching blood and body fluids. Wearing gloves may provide some protection against needlestick injuries (21). Gloves should be changed and hands washed thoroughly after contact with each patient. Handwashing and, when appropriate, glove and gown use are very important procedures in preventing nosocomial infections (22).

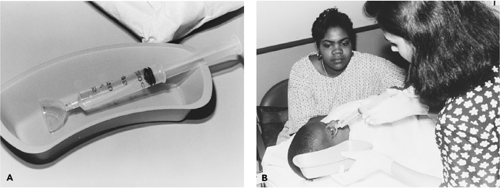

Masks and protective eyewear (a face shield will work as both) should be worn to protect the mucous membranes of the face when procedures are performed that could generate a spray of blood or blood-containing body fluids (e.g., wound irrigation, endotracheal intubation, and naso/orogastric tube placement). Impervious gowns should be worn when there is profuse bleeding or procedures are performed that could create splashes of blood or blood-containing body fluids (e.g., arterial line placement, central line placement, cutdown, and thoracostomy tube placement) (Fig. 8.1). Mouth-to-mouth resuscitation should be avoided, and alternative ventilation devices should be used (e.g., bag-valve-mask ventilation).

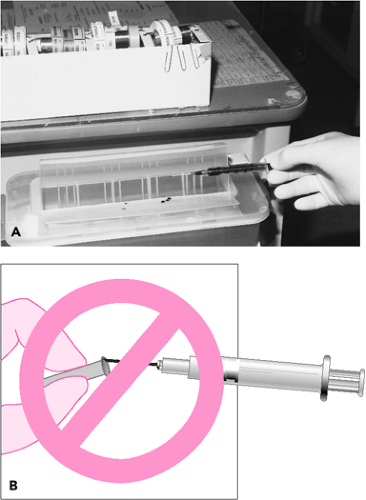

Needles should never be recapped, bent, or broken by hand. All sharp objects should be handled with exceptional care. Puncture-resistant containers should be used for needle and sharp instrument disposal. These containers should be readily accessible and, if possible, within arm’s reach of the working area (Figs. 8.2A,B).

Universal precautions will be useful in preventing the occupational transmission of bloodborne and other pathogens only if HCWs adhere to them. Studies from EDs and other health care settings have demonstrated that use of gloves and other barrier precautions by HCWs is far from universal (23,24,25,26,27). Educational interventions have been somewhat successful

in improving HCW compliance with universal precautions (28,29,30). The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) issued regulations that mandate HCWs to wear gloves for all phlebotomy procedures in hospitals and that also mandate hospital personnel to train their employees annually regarding the reasons for wearing gloves during all phlebotomy procedures (31). HCWs can be fined for infractions.

in improving HCW compliance with universal precautions (28,29,30). The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) issued regulations that mandate HCWs to wear gloves for all phlebotomy procedures in hospitals and that also mandate hospital personnel to train their employees annually regarding the reasons for wearing gloves during all phlebotomy procedures (31). HCWs can be fined for infractions.

TABLE 8.1 Infection Control Requirements for Exposure to Body Fluids and Procedures Performed in the Emergency Department | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The reasons for poor compliance with universal precautions by HCWs are numerous. They include lack of time to put on protective materials, uncomfortable protective materials, failure to remember, judging the patient not high risk, and interference with proficient performance of procedures. In particular, HCWs often complain that they cannot perform vascular access procedures when wearing gloves. However, investigators from Philadelphia reported no difference in the success rate on the first attempt at vascular access with

and without wearing gloves by nurses and residents in a pediatric ED (28). HCWs should be advised that retraining can be easily accomplished through practice and patience.

and without wearing gloves by nurses and residents in a pediatric ED (28). HCWs should be advised that retraining can be easily accomplished through practice and patience.

Figure 8.1 The pediatric trauma team prepares for patient arrival with gown, mask, goggles, and gloves. |

Figure 8.2 A. The proper disposal of contaminated needles. B. Needles should never be recapped before disposal. |

Figure 8.3 Improper, careless scattering of used needles and sharps, including their insertion into a mattress, creates a hazardous environment for health care workers. |

Universal precautions are very effective at protecting against cutaneous and mucous membrane exposures to blood and body fluids. However, percutaneous exposure from needlestick and sharp instrument injuries accounts for the vast majority of occupational HIV and HBV transmissions. In a study of 1,201 HCWs exposed to blood or body fluids of HIV-infected patients, needlestick injuries accounted for 80% of the exposures, and sharp instruments for 8% (32). Exposure causes included manipulating needles (36%), recapping needles (17%), and improper disposal of sharp objects (14%). Two exposures that led to HIV seroconversion resulted from needlestick injuries inflicted by coworkers during resuscitation procedures (Fig. 8.3).

Training and educating HCWs to take extraordinary precautions while handling sharp items is not sufficient. In addition to implementing universal precautions, hospitals must continue to create a safer working environment for HCWs, government bureaus must continue to enact safety regulation guidelines, and industry must create safer devices (33).

Figure 8.4 The Biojector 2000, an advanced needle-free system for intramuscular and subcutaneous injections, was engineered by Bioject Inc. of Portland, Oregon. |

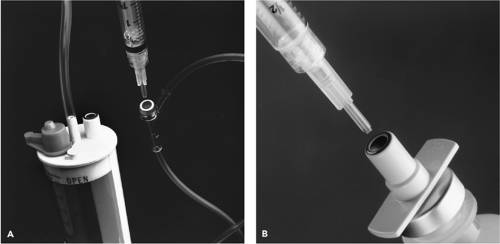

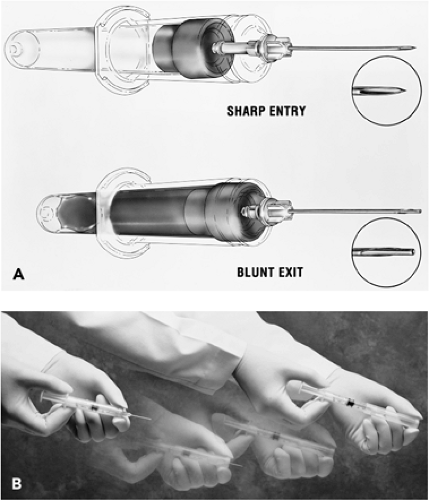

In 2000, the Needlestick Safety and Prevention Act became law, and in response OSHA revised Bloodborne Pathogens Standard 1910.1030. The standard requires employers to provide safer needle devices that have been developed and marketed (20,34,35) with input from HCWs. At least 340 patents for sharp safety devices had been issued, and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) had approved for marketing at least 88 needlestick prevention devices (36). Examples of devices to perform procedures with fewer sharp instruments include compressed-air injection systems (Fig. 8.4), needleless i.v. and vial access systems (Fig. 8.5), and needles

that can be used and disposed with no risk of injury (Fig. 8.6A,B).

that can be used and disposed with no risk of injury (Fig. 8.6A,B).

The vast majority of blood contacts by HCWs are cutaneous. Latex gloves provide reliable protection against cutaneous exposure to blood and body fluids; however, they do not preclude needlestick or sharp instrument injuries. Wearing two pair of gloves can decrease the risk of inner-glove perforation (21). Cut-resistant glove liners designed to be worn under latex gloves are available. Recently, manufacturers have redesigned the suture needle in an attempt to reduce inadvertent needlestick injuries. One product, the Ethiguard Blunt Point needle (Ethicon Products), claims to have reconfigured the tapered end of the needle to reduce needlesticks while maintaining tissue penetration during suturing.

In many EDs, a simple needleless device is used to irrigate wounds, which prevents splash of blood-contaminated irrigation fluid (Fig. 8.7A,B). This product is a clear plastic, parabolic cup that attaches to the tip of a Luer-Lok or slip-tip syringe. Its self-contained nozzle creates a high-pressure stream for irrigation, while the shield protects against contaminated splashback.

Disposable gloves, masks, protective eyewear, impervious gowns, sharp containers, and the newly developed safe needles and other safety devices are expensive, (37); however, they are currently our best protection against occupational acquisition of bloodborne and other pathogens. The benefit of possibly preventing cases of occupationally acquired HIV, HBV, or other infections far outweighs the costs of barrier protective materials and the new safer devices.

Selected Infections That Occur following Exposure to Blood or Secretions

Although the use of universal precautions is the recommended approach in caring for all patients, it is prudent to review some of the more common infections that could affect HCWs. Despite careful adherence to infection control procedures and policies during the management of acutely ill or injured patients, exposures will occur. In evaluating the risk of exposure and infection after exposure, the HCW should consider the infectious agent, the mode of transmission, his or her individual susceptibility, the type of contact exposure, and whether

the patient or situation is high risk. Table 8.2 outlines the more common infectious diseases in terms of source of exposure, transmission and incubation, and risk of infection following exposure.

the patient or situation is high risk. Table 8.2 outlines the more common infectious diseases in terms of source of exposure, transmission and incubation, and risk of infection following exposure.

Figure 8.7 A. A clear plastic splash guard attached to an irrigation syringe. B. Irrigation of a laceration using the syringe–splash guard technique. |

TABLE 8.2 Summary of Potential Infectious Diseases Following Exposure to Blood and Secretions | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

HIV

HCWs exposed to HIV-infected blood or secretions are rarely infected. As of December 2001, 57 HCWs had been reported to the CDC with HIV infection associated with an occupational exposure and no other risk factors. The risk of infection after a needlestick exposure to HIV-infected blood is approximately 0.3% (1,2,38). A case control study revealed that significant risk factors for HIV seroconversion following needlestick injury are deep injury, visible contamination with source patient’s blood, procedure associated with needle placement into the patient’s vein or artery, and exposure to a patient who died of AIDS within 2 months following the incident. HIV infection following mucous membrane exposure is approximately 0.09% (39,40). Proper handling and disposal of needles will prevent a majority of these exposures (41). In November 2002, the FDA approved OraQuick for point-of-care testing for HIV-1. Many studies have validated that the sensitivity and negative predictive value are equal to the traditional EIA for anti–HIV-1 IgG (42). If exposed, HCWs should contact the employee health department in their institution for counseling and testing. Table 8.3 outlines the steps to take after accidental exposure. All institutions should have a protocol in place to deal with needlestick injuries.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree