Promoting Healthy Sleep Practices

Allowing for Adequate Sleep Time

Although it is known that individual sleep requirements can vary significantly, there are reliable guidelines to help establish target total sleep times by age. Sleep need varies throughout the life span with infants sleeping 14–15 hours per day, toddlers sleeping 12–14 hours per day, preschoolers sleeping 11–13 hours, school-aged children sleeping 10–11 hours, and teenagers needing 8.5–9 hours per day.1 Epidemiological research suggests that children and adolescents are frequently getting less sleep than needed. The 2004 Sleep in American Poll found that 54% of school-aged children are getting less than 10 hours of sleep per day; the median hours of total sleep time among children aged 6–10 year was 9.5 hours.2 Eighty percent of parents reported that their children are getting ‘just the right amount of sleep,’ suggesting that parents are aware of the increased sleep need among children and adolescents as compared to adults. In addition, 27% of school-aged children were getting more sleep on the weekends, suggesting that these children are building up a sleep debt throughout the week and have significant variability in their sleep–wake schedule between school days and weekends.6

Consequences Associated with Insufficient Sleep

Insufficient total sleep time among children and adolescents has been associated with significant health consequences. A recent meta-analysis which included 12 studies (with data for over 30 000 children) found that short sleep duration was significantly associated with increased weight, defined as a body weight greater than 85th percentile for age.3 Furthermore, short sleep time is associated with metabolic changes (e.g., insulin resistance, increased fasting plasma glucose) among overweight and obese children.4 In a longitudinal study of 200 children from birth to 5 years, normal-weight and overweight children did not differ in terms of nighttime sleep duration; however, overweight children demonstrated significantly less daytime napping, and thus shorter total sleep times.5 While these studies highlight the importance of adequate total sleep time, a potential moderating factor of the relationship between sleep duration and weight may be timing of sleep. In the Spruyt et al. study of 2011, variability in total sleep time was associated with metabolic changes, as was total sleep time itself. Similarly, a recent study found that adolescents with later bedtimes and rise times were significantly more likely to be overweight as compared to adolescents with earlier bed- and rise-times, despite similar total sleep times between the two groups.6

Developing Healthy Sleep Habits

Traditionally, the term ‘sleep hygiene’7 has been used to include a wide variety of behaviors aimed at creating an environment conducive to sleep and avoiding activities that are disruptive to sleep. Although education about good sleep hygiene is frequently used as part of treatment for insomnia in adult populations, there is no standard definition of sleep hygiene.8 For example, good sleep hygiene in adults is commonly presented as: (1) maintaining a cool, quiet, and dark sleep environment, (2) avoiding caffeine and alcohol near bedtime, and (3) not watching television or reading in bed, representing a conceptual overlap with stimulus control treatment for insomnia.9 Given the non-standard definition of sleep hygiene, the present chapter instead presents recommendations to promote ‘healthy sleep practices’ among children and adolescents. Specifically, the chapter will review the importance of allowing for adequate time for sleep, maintaining a consistent sleep–wake pattern, creating a comfortable sleep environment, avoiding physiological barriers to sleep, and establishing effective bedtime routines. This chapter will not focus on specific treatments for childhood insomnia, as this is presented elsewhere (see Chapters 16 and 17).

Maintaining a Consistent Sleep–Wake Pattern

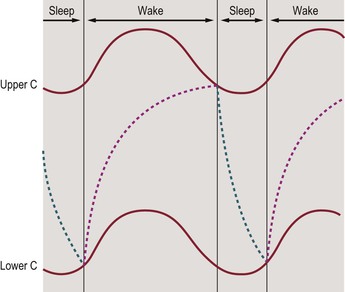

As currently understood, the sleep–wake cycle depends on the interactions between two processes: process C, the circadian wakefulness drive, and process S, the homeostatic sleep drive. These processes are presented in Figure 8-1.10

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree