2King’s College London and Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK

Overview

- Prognostic factors are useful in guiding therapeutic decisions

- Axillary node metastasis, histological tumour grade and tumour size are the most powerful prognostic factors

- Oestrogen receptor and HER2, while prognostic, also have value in selecting treatment as both are targets for therapy

- Multiple molecular and biological markers have been identified, but few are, as yet, of clinical benefit

- Microarray (RNA) based technologies are in clinical trials being compared against conventional clinical prognostic and predictive parameters

Prognostic factors are of value for three main reasons:

- To predict outcome for an individual patient.

- To allow comparisons of treatment between groups of patients at similar risk of recurrence and death.

- To improve our understanding of breast cancer and develop new therapeutic approaches.

Prognostic factors should:

- Have clear biological significance.

- Be applicable to clearly defined patient populations.

- Be based on robust, reproducible data.

Prognostic factors put individual patients in a low- or high-risk group that indicates a relative rather than an absolute prediction of the future behaviour of the disease. The patient profile cannot always predict prognosis precisely. The factors often interrelate with each other. Nonetheless, they are useful in guiding therapeutic decisions, and biological factors are becoming more helpful, especially in predicting a patient’s response to certain types of treatment.

Clinical Factors

Tumour Size

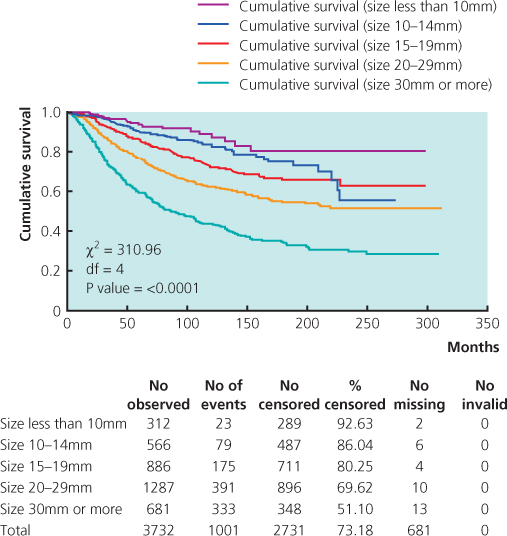

The size of a cancer, as measured by the pathologist on the fresh or fixed macroscopic specimen and confirmed or amended after histological examination, correlates with survival (Figure 14.1). Patients with smaller cancers have a better survival than those with larger tumours.

Figure 14.1 Overall survival by invasive tumour size in 3732 primary operable invasive breast cancers. From Nottingham Tenovus Primary Breast Cancer Series.

Axillary Status

Axillary nodal metastasis that has been proven by histology is the most powerful prognostic factor in breast cancer in the majority of studies. Survival is correlated directly with the number and level of axillary lymph nodes involved (Table 14.1; and see Chapter 9).

Table 14.1 Survival of patients with breast cancer according to involvement of axillary lymph nodes.

| Lymph node involvement | Survival at 10 years (%) |

| All patients | 66 |

| Negative axillary nodes | 77 |

| Positive axillary nodes | 45 |

| 1–3 | 51 |

| ≥4 | 30 |

Recent interest has focused on the assessment of small deposits of tumour within axillary lymph nodes known as micrometastases. Different definitions for these micrometastases are used with different methods of identification, including step sectioning, immunohistochemistry and reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction. Their importance, however, is unclear. The new tumour node metastasis staging system uses a pragmatic definition of a micrometastasis as measuring between 0.2 mm and 2 mm in size. Such metastatic foci are treated in a similar manner to negative nodes in terms of therapeutic decision making. Isolated tumour cells are classified as node negative.

Metastatic Disease

Patients with metastatic disease, particularly the 10% of patients with overt metastases at the time of presentation (M1 or stage IV disease), have a poorer prognosis than those with apparently localised disease. Survival differs according to the site of disease. Patients with supraclavicular fossa disease have a better survival than patients with metastatic disease at other sites. Patients with bone metastases and no visceral metastases have a better outlook than those with visceral disease.

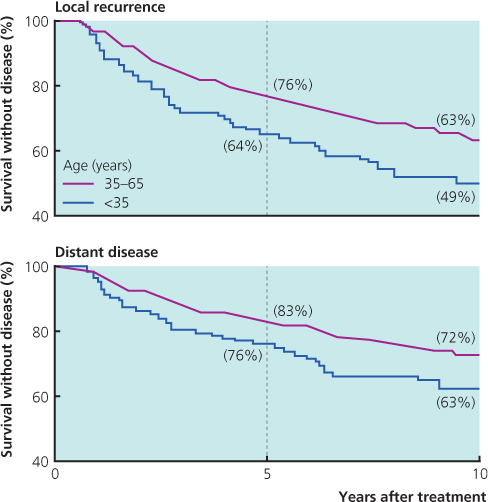

Age

Young women (particularly those <35 years) have a poorer prognosis than older women who have the disease at an equivalent stage (Figure 14.2). Being young is a marker for recurrence of local disease and, hence, distant disease.

Figure 14.2 Freedom from recurrence of cancer in patients in relation to age when breast cancer first diagnosed (proportional hazards model showed women <35 to have a relative risk of 1.6 for distant disease).

Histological Factors (Table 14.2)

Table 14.2 Histological markers of prognosis.

|

|

Histological Grade

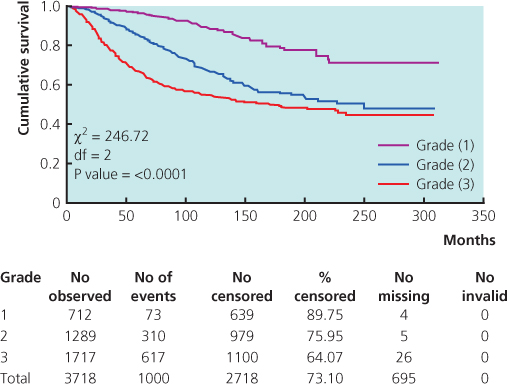

Histological grade is assessed on tubule formation, nuclear pleomorphism and mitotic frequency, and the assessment is done by a trained pathologist. Three histological grades (1, 2 and 3) correlate with survival (Figure 14.3; see Chapter 8). The quality of fixation (and hence preservation of cellular architecture) is critical in determining the tumour grade accurately.

Figure 14.3 Overall survival by histological grade in 3718 primary operable invasive breast cancers.

Histological Type

Special types of invasive breast cancer, including tubular, mucinous and invasive cribriform cancer, are associated with a better prognosis than invasive carcinoma of ductal/no special type (see Chapter 8). In addition, histological type provides information about the biological behaviour of invasive breast carcinoma—for example, invasive lobular carcinomas will probably be oestrogen receptor positive, lack p53 expression, have a low proliferation rate and metastasise in a different pattern of spread to invasive ductal cancers.

Lymphovascular Invasion

In the breast, it may not be possible to distinguish lymphatic channels from blood vessels on routine haematoxylin and eosin-stained sections, so the term lymphovascular invasion is used. Tumour cells in the lumen of lymphovascular channels are present in up to a quarter of patients with breast cancer (see Chapter 8).

Lymphovascular invasion is associated with local disease recurrence and a high risk of short-term systemic relapse.

Other Histological Markers

Peritumoral angiogenesis, and micrometastases within draining lymph nodes (whether detected by histology, immunohistochemistry or molecular-enrichment techniques such as the polymerase chain reaction) require more evidence to determine whether they have prognostic importance.

Prognostic Indices

Many histological and biological factors that determine prognosis are interrelated. Some are difficult to determine, and many do not have confirmed independent prognostic value. The Nottingham Prognostic Index (NPI) (Box 14.1) incorporates invasive tumour size, lymph node status and histological grade.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree