Introduction

This chapter will outline the basic principles of obstetric analgesia and anesthesia and deal with those borderline issues where the anesthesiologist interacts with the generalist obstetrician, maternal-fetal medicine specialist or medical specialist, or where the decisions of one group of clinicians impinge on another. The best clinical practice principles for a broad range of situations where joint management is necessary are reviewed.

In all patients, but especially in those with significant maternal disease, a focused, directed history, past and recent history and chart review and physical examination prior to undertaking an anesthetic procedure reduce maternal, fetal and neonatal complications [1,2]. Particularly for those with concomitant medical problems, early referral to and consultation with the anesthesiologist is essential [2,3].

Principles of regional anesthesia for normal labor and delivery

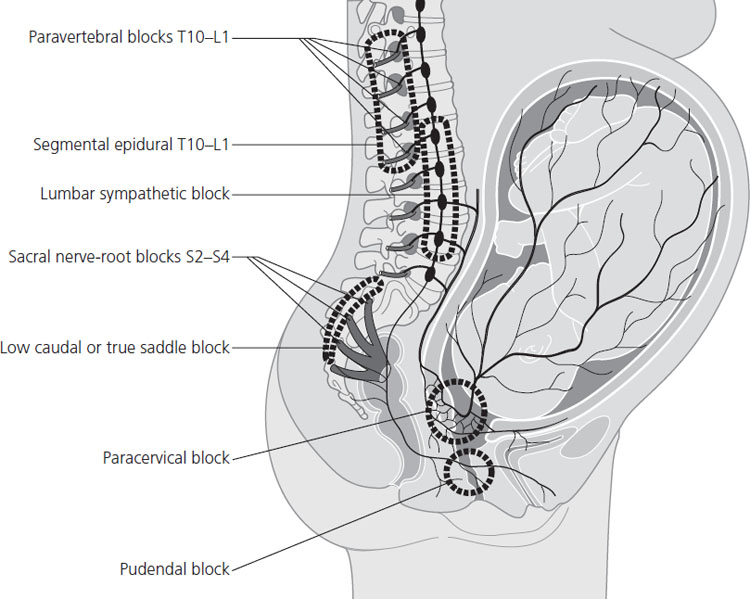

Labor pain is caused mainly by uterine contractions, myometrial ischemia, and cervical stretching and distension, transmitted via the sympathetic (T10–L1) and somatic (S2–S4) afferent nerve pathways (Figure 29.1). These nerves project information to the autonomic, hormonal and somatosensory centers of the brain. Labor can also be viewed as an inflammatory process mediated by interleukins, tumor necrosis factor, nitric oxide, and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2).

Figure 29.1 Innervation of the uterus, cervix and vagina. This figure also shows the site of paravertebral, epidural, lumbar sympathetic, sacral, caudal, paracervical and pudendal nerves blocks. Reproduced with permission from Eltzschig et al. [5].

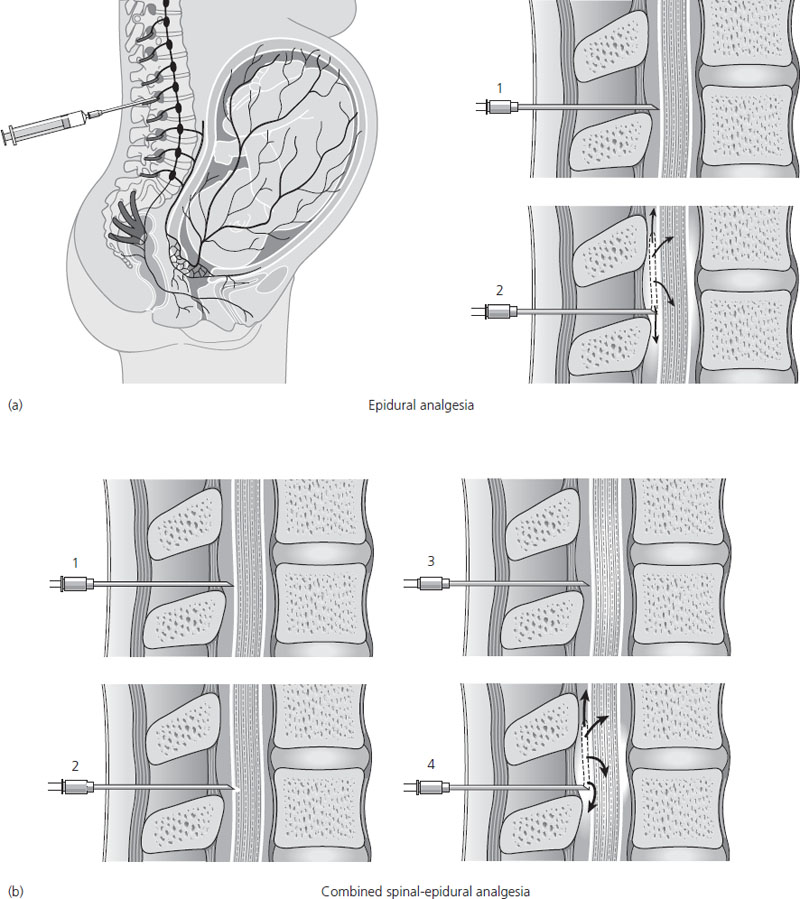

Although the use of epidural analgesia for childbirth varies greatly throughout the world, approximately 60% of women in the USA and UK will choose epidural analgesia for pain relief during childbirth [4]. Labor pain is transmitted through lower thoracic, lumbar, and sacral nerve roots that are amenable to epidural blockade [5]. Epidural analgesia is achieved by placement of a catheter into the lumbar epidural space; this space surrounds the spinal column and allows analgesic medication to be administered directly to the appropriate afferent nerves. Solutions of a local anesthetic, an opioid or both can then be administered as intermittent boluses, a continuous infusion or a patient-controlled technique (PCEA). The technique of combined spinal-epidural (CSE) has gained popularity in recent years. With this, a single bolus of an opioid, or opioid and local anesthetic, is injected into the spinal space, in addition to the placement of an epidural catheter (Figure 29.2). The main advantage of CSE is extremely rapid onset of pain relief due to the rapid onset of the spinal component, with minimal motor blockade due to the extremely low dose of drug. The principal goal of labor analgesia is to produce sufficient pain relief without interference with motor function, to allow maximal participation from the mother during the expulsive phase of labor. The PCEA technique of epidural administration has become very popular, as it allows the patient to titrate to her particular desired level of analgesia, while minimizing side effects and providing maximal maternal satisfaction.

Figure 29.2 (a) Epidural block showing site of needle insertion and location of tip of epidural needle and catheter. (b) Combined spinal epidural block showing (1) epidural needle placement, (2) spinal needle placement, (3) spinal needle removal, (4) epidural catheter placement. Reproduced with permission from Eltzschig et al. [5].

Regional anesthesia can cause hypotension, due to sympathetic block, as well as profound pain relief. The hypotension is usually more frequent during cesarean delivery, owing to the higher level of anesthetic block required, but can be a complication of labor analgesia as well. Common methods used to prevent hypotension include intravenous fluid administration, maintenance of lateral tilt position, and in some cases prophylaxis or treatment with a vasopressor, such as ephedrine, metaraminol or phenylephrine.

The Task Force on Obstetric Anesthesia of the American Society of Anesthesiologists has recently critically reviewed all available literature and produced guidelines with a view to enhancing quality of anesthesia care, improving patient safety, reducing complications and increasing patient satisfaction [2]. These recommendations, as they apply to obstetric medicine, can be summarized as follows.

- No parturient should be denied pain relief in labor. The guidelines state that “Maternal request represents sufficient justification for pain relief.”

- Epidural, spinal and combined spinal-epidural (CSE) anesthetic techniques can improve maternal and neonatal outcome. Parturients in early labor at less than 5 cm dilation can be safely offered neuraxial techniques without increasing their cesarean delivery or instrumental delivery risk compared to parenteral opioid analgesic techniques. Regional blocks do not increase risk to the fetus or neonate [6].

- In complicated parturients (e.g. twin gestation, pre-eclampsia, morbid obesity) early insertion of an epidural or spinal catheter reduces maternal complications.

- Neuraxial (epidural or spinal) catheter techniques are the best available modality for pain relief. They are efficacious, safe, flexible and versatile in the ability to offer good pain relief for a variety of clinical situations.

- Continuous infusion epidural local analgesia using local anesthetics with or without opioids, or spinal opioid with or without local anesthetic, provide better-quality analgesia than parenteral (IV or IM) opioid.

- Modern neuraxial analgesia does not increase the likelihood of cesarean delivery compared to parenteral opioid analgesia.

- The primary goal of neuraxial labor analgesia is to provide good sensory analgesia with a minimum amount of motor block. The lowest concentration of local anesthetic infusion that provides adequate maternal analgesia should be chosen. In most instances, this can usually be achieved with concentrations of 0.125% (or lower) of bupivacaine or ropivacaine.

- Compared to parenteral opioids, regional blocks do not significantly increase the duration of labor, decrease the incidence of vaginal delivery or increase the incidence of maternal, fetal or neonatal side effects.

- Addition of opioids to local anesthetics for both epidural and spinal techniques improves analgesia.

- For spinal analgesia, pencil point needles are better than cutting-bevel spinal needles in reducing the incidence of postdural puncture headache.

The trend towards using weaker local anesthetics (and combining them with opioids) for labor has brought major benefits – greater mobility, less motor blockade, fewer instrumental deliveries and less dystocia. All these techniques and agents aim at good pain relief coupled with retention of the maximum degree of control and the least interference with the pelvic muscles, the ability to push and to be ambulatory (or, at the very least, to be mobile). The optimal way to achieve these aims is either by using a CSE using opioid +/− a tiny dose of local anesthetic in the spinal component, or with an epidural with low-dose local anesthetic and opioid. Both methods have proven to be effective and safe [4–6].

Principles of general anesthesia for cesarean delivery

In most situations, a regional anesthetic technique, albeit with some modifications tailored to the individual clinical situation, is preferable to general anesthesia and is often considerably safer for both mother and neonate. Nevertheless, there are situations, e.g. extreme urgency (due to rapid administration of general anesthesia), bleeding diathesis (due to possibility of epidural hematoma), generalized or local infection (due to possibility of epidural abscess), in which regional anesthesia may be absolutely or relatively contraindicated.

The standard, universal regimen for general anesthesia for cesarean delivery (CS) is used worldwide and is molded around a rapid-sequence induction, an anesthesia maintenance plan which is modified once the neonate is delivered and a course of action, the failed intubation algorithm [7–10], if intubation fails or proves difficult [11–15].

There are several reasons why the technique has gained such widespread acceptance.

- It allows anesthesiologists to secure the airway immediately under quasi-ideal intubating conditions.

- It has the lowest impact possible on the fetus such that the newborn is delivered with the lowest possible degree of depression.

- The technique is forgiving in that, if the intubation fails [16], there is a fair chance that the parturient will awake and breathe spontaneously before severe hypoxemia supervenes so that an alternative technique (e.g. laryngeal mask airway [16], spinal subarachnoid or epidural block) can then be tried.

- It virtually eliminates the incidence of maternal awareness.

- It provides maximum protection against pulmonary acid aspiration even in mothers with a full stomach.

- Anesthesia can be achieved within seconds so that delivery can start immediately, even in the most dire emergencies, and the distressed fetus can be delivered within minutes.

- General anesthesia (GA) can be achieved with relatively cheap and readily available medications and equipment.

- This GA sequence provides good surgical operating conditions.

The core of the rapid-sequence induction (RSI) technique consists of optimal preoxygenation, intravenous induction (using thiopental/thiopentone or propofol) followed by a rapid-acting neuromuscular block (usually succinylcholine) and endotracheal intubation under cricoid pressure, to prevent passive regurgitation of gastric contents. Anesthesia is then maintained using inhaled volatile agent (e.g. isoflurane, sevoflurane or desflurane). After delivery, the volatile concentration is reduced (as volatile inhalation agents can contribute to uterine atony) and an opioid (e.g. morphine, fentanyl, hydromorphone) and additional muscle relaxant, together with oxytocin and/or carbetocin, are administered.

Aspiration pneumonitis prophylaxis

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree