Principles of Infection Control

INTRODUCTION

An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.

The importance of appropriate and sustained infection prevention and control (IP&C) practices in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) cannot be overstated as infants in the NICU are extremely vulnerable to health-care-acquired infections (HAIs). This chapter introduces the basic components of an IP&C program, including the roles of workforce health and safety and the clinical microbiology laboratory. In addition, strategies to reduce HAIs in the NICU, including staff education, transmission precautions, and bundle practices to reduce central-line-associated bloodstream infections (CLABSIs) and ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) are described. Reduction of HAIs must be accompanied by effective surveillance for HAIs and multidrug-resistant organisms (MDROs). This is particularly important in an era of mandatory reporting. Finally, this chapter describes evidence-based antimicrobial stewardship interventions.

Throughout the chapter, citations are provided from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC) authoritative guidelines on prevention strategies for HAIs. This federal advisory board has infection control experts from the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA), Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA), and the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP).1 In addition, the CDC provides guidelines and tools through the National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) system to assist hospitals to develop surveillance, analysis, and reporting systems for HAIs that can enable interventions, when necessary (http://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/).

Discussion of the pathophysiology and treatment of bacterial and viral pathogens, including MDROs, is beyond the scope of this chapter; these topics are addressed in other chapters in this guide.

COMPONENTS OF INFECTION PREVENTION AND CONTROL PROGRAMS

Administrative Support

Administrative support is crucial to secure the resources and infrastructure needed to provide an effective IP&C program to serve the NICU. As NICUs are part of larger hospitals and health care systems and may be the only pediatric unit within some hospitals, the administrative leadership should be educated by the IP&C program and NICU leadership about the unique needs of the neonatal population. Elements of education should include the types of HAIs that neonates can acquire; the morbidity associated with these infections (ie, increased length of stay, health care costs, and potential mortality); preventive strategies and the cost of such strategies, including maintaining adequate bedside nurse staffing; reporting requirements to institutional committees, local health departments, and other regulatory bodies; relevant Joint Commission patient safety goals and priorities; the potential impact of HAIs on hospital reputation; and the role of families and visitors.

Support for IP&C efforts must be provided by NICU medical and nursing leadership as well as the bedside health care professionals and ancillary caregivers (eg, respiratory therapists, radiology technicians, phlebotomists, and environmental service workers). Regular presentations should be made to the administrative leadership and the NICU team by the IP&C staff, who should serve on the NICU quality council. These presentations should describe the results of both process measures to prevent HAIs and outcome measures of HAI rates as described in this chapter.

Infection Prevention and Control Staff

There is no universally accepted staffing requirement for IP&C, but a Delphi panel suggested a ratio of 0.8 to 1.0 infection preventionists per 100 occupied acute care beds based on time estimates for infection control functions.2 However, experts emphasized that more research is needed to identify effective staffing levels that consider the expanding surveillance and reporting responsibilities of IP&C staff.3 Given the high rates of HAIs in NICUs, dedicated IP&C staff should serve the NICU and measures be taken to ensure appropriate resources for effective education, surveillance, mandatory reporting, and implementation of preventive strategies.

Additional IP&C program requirements include a director (generally a physician trained in infectious diseases and IP&C), data manager/analyst, and administrative assistant. In addition, close collaborations with the workforce (employee) health service (WHS), clinical microbiology laboratory, and pharmacy are critical (see the following discussion). Infection control liaisons (eg, staff members from nursing units) are helpful in facilitating implementation of IP&C strategies.

Workforce (Employee) Health Service

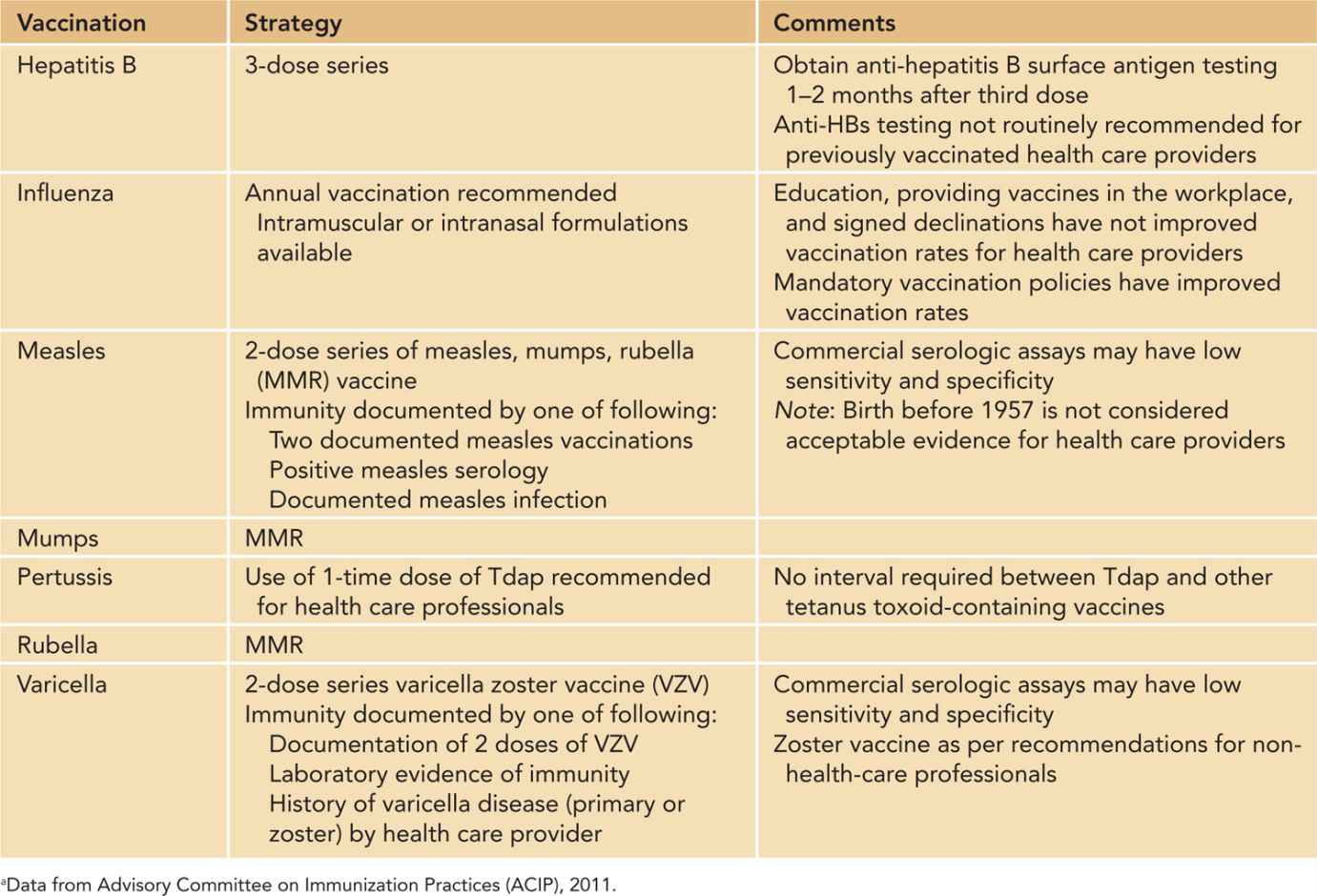

The WHS is an integral part of IP&C and is charged with preventing transmission of potential pathogens from staff to patients and from patients to staff. Strategies to prevent transmission include primary prevention through vaccination (see Table 6-1 for 2011 Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices [ACIP] recommendations for health care workers)4; screening for latent tuberculosis infection; banning artificial nails and promoting skin care5,6; and policies to prevent staff from working ill. Mandatory vaccination requirements vary from state to state, and compliance is reviewed by the Joint Commission, which is currently recommending that facilities increase annual influenza vaccination rates. As recommended by the ACIP, health care professionals should have documented evidence of presumptive immunity to hepatitis B, measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella. Health care professionals should be vaccinated annually for influenza and receive a single dose of Tdap as soon as feasible.4

Table 6-1 Current Recommendations for Vaccinations for Health Care Providers in the United Statesa

The WHS must have written policies (crafted with the IP&C Department and human resources) for furloughing, paying, and returning to work staff who are infected or colonized with potentially communicable pathogens. Policies should be developed for vaccine-preventable illnesses as well as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), influenza-like illness, gastrointestinal tract illness, herpes stomatitis, and varicella zoster, to name a few.

Clinical Microbiology Laboratory

The clinical microbiology laboratory contributes greatly to preventing transmission of infectious diseases in the NICU because the laboratory is responsible for identifying epidemiologically important microorganisms (see the section on surveillance that follows), detecting changes in resistance patterns, and implementing rapid diagnostic testing for viruses. The clinical microbiology laboratories that serve NICUs may be on-site hospital laboratories that serve several patient populations or off-site contract laboratories. Nonetheless, laboratories should be able to support the IP&C Department and provide the frequency of specific pathogens in the NICU (eg, MRSA); antibiograms (ie, aggregate reports of susceptibility to specific agents); and assist in outbreak investigations, including the ability to save isolates, perform surveillance cultures, and arrange for molecular typing of selected isolates, when needed.

Policy and Procedures for Devices, Supplies, and Equipment

Policies and procedures must be developed for use of all devices, including insertion strategies, maintenance practices, and disinfection/sterilization, when appropriate. It is not uncommon for the NICU team to consider a new product (eg, catheter hub, Y connector) or new piece of equipment (eg, isolette, glucose monitor). Although staff satisfaction is clearly important when considering a change, infection control implications must also be considered. For example, how is the product cleaned, disinfected, or sterilized? Has the product been associated with an increased risk of malfunction or HAIs? Are single-use medications available because multiuse vials can become contaminated?

STRATEGIES TO PREVENT HAIS IN THE NICU

Education

Education of health care professionals as well as families and visitors is crucial to promote appropriate IP&C in the NICU. The optimal methods of education are actually unknown, but posted signs, electronic learning sites, small-group huddles, interactive audience response systems, and didactic lectures can be used. Mandatory education can be used as a component to demonstrate competencies. Notably, health care professionals should receive “booster” education at regular intervals to reinforce IP&C principles and practices. Education about hand hygiene, the rationale for different transmission precautions, respiratory hygiene/cough etiquette, and vaccinations should be provided to families and visitors as well.

However, education alone cannot improve practices. Practices are improved by a combination of education, strategies to improve adherence such as checklists or observations of desired practices (process measures) with feedback to staff, and providing HAI rates (outcome measures) to key stakeholders. In addition, during the past decade there has been increasing attention to creating a culture of safety and quality in health care.

Hand Hygiene

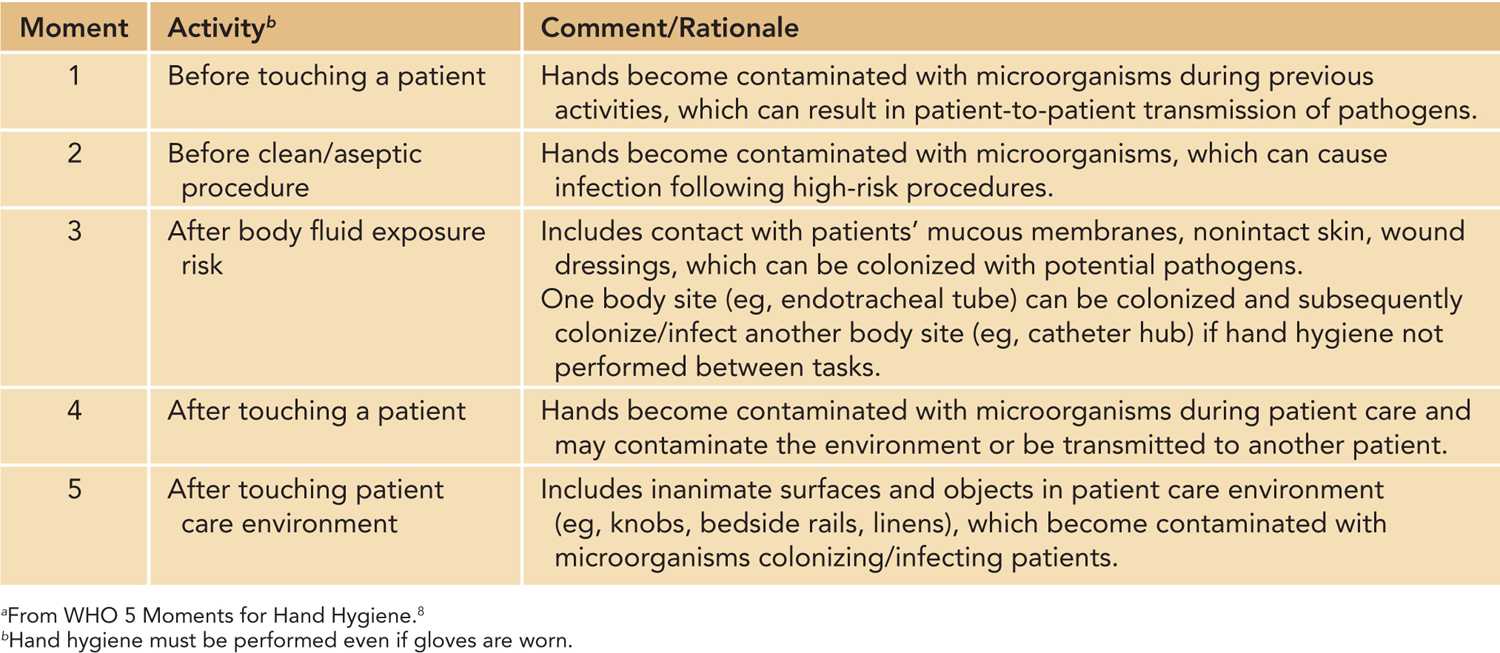

For over 150 years, hand hygiene has been recognized as the most effective way to prevent HAIs. Despite the relative ease and low cost of this intervention, adherence rates by health care professionals have been less than 50% in many studies, and physicians generally have lower rates than nurses.7 Both the CDC and the World Health Organization (WHO) have developed guidelines for hand hygiene that include how and when to perform hand hygiene.8 The WHO’s 5 Moments for Hand Hygiene (representing 5 fingers) are shown in Table 6-2. A WHO video, SAVE LIVES: Clean Your Hands, is available for the education of health care professionals (http://www.who.int/gpsc/5may/video/en/index.html).

Table 6-2 World Health Organization’s Five Moments for Hand Hygienea

When compared to soap and water, alcohol-based hand rubs are preferred; this method is less costly, less time consuming, less damaging to skin, and effective against gram-negative and gram-positive pathogens as well as yeast and most viruses. Hands should be washed with soap and water when visibly soiled with blood or body fluids or visibly dirty. Other aspects of hand hygiene include minimal-to-no-jewelry; short, well-groomed nails; no artificial nails or nail enhancements; and maintenance of good skin health (ie, avoiding contact with solutions in the non-health care environment that can dry hands, applying moisturizer frequently outside the NICU, and seeking prompt medical attention for dermatitis or other skin or nail lesions, eg, paronychia, whitlow, onychomycosis).

Adherence to hand hygiene should be monitored and rates shared with staff. Adherence can be greatly facilitated by having the NICU team participate in the selection of products and by ensuring adequate hand hygiene supplies. NICU staff should also participate in selecting the locations where the dispensers are located. If wall space is limited, additional dispensers can be placed at the bedside. All visitors to the NICU, including siblings, should practice hand hygiene before and after visiting their infant. Bedside staff are responsible for teaching appropriate use of alcohol hand rub material and observing the practice to ensure proper use.

Transmission Precautions

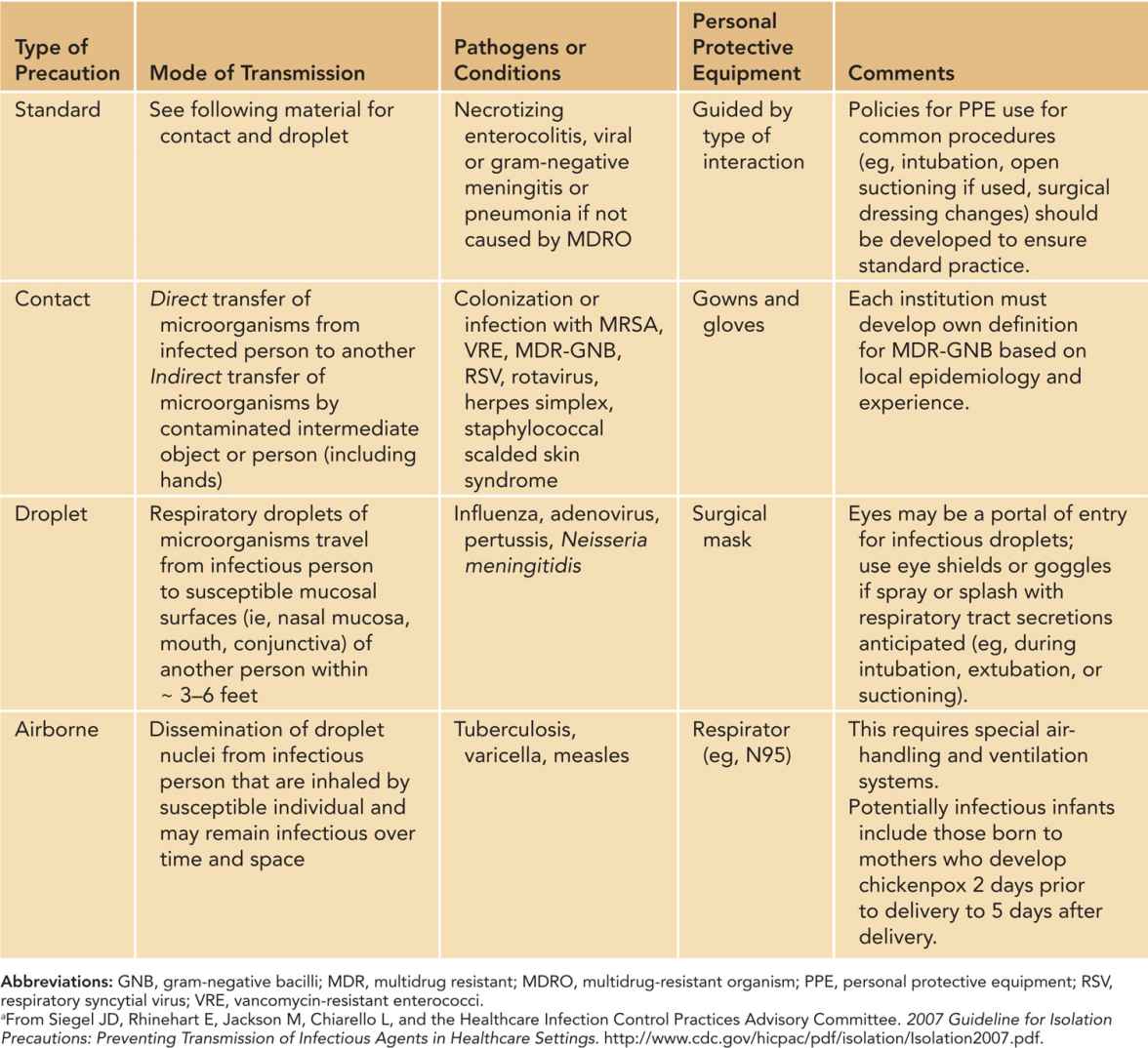

Two recent evidence-based guidelines from HICPAC address prevention of transmission of MDROs9 and transmission precautions.10 Standard precautions and contact precautions are the most frequently used transmission precautions in the NICU; droplet and airborne precautions are rarely implemented, but nonetheless should be understood by NICU staff. The personal protective equipment (PPE) worn by health care professionals caring for patients on transmission precautions and examples of specific pathogens for different types of precautions are shown in Table 6-3. NICUs should ensure that an adequate supply of gowns and gloves (in different sizes) is available and that restocking and appropriate disposal of PPE waste occur often. Hand hygiene is always performed before and after gloves are donned.

Table 6-3 Implementation of Transmission Precautions in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unita

The terms and concepts for standard precautions have replaced the former term universal precautions. The principles underlying standard precautions are the foundation of prevention of transmission of infectious pathogens during patient care and include appropriate use of PPE, respiratory hygiene/cough etiquette, and safe handling of blood and body fluids, including phlebotomy practices. The rationale for standard precautions is that any patient could be harboring a potential pathogen that could be transmitted to another patient or to a health care professional during care. Thus, in addition to hand hygiene, gloves should be worn by all health care providers for all patients when touching blood, body fluids, secretions, excretions, mucous membranes, nonintact skin, and contaminated items. Gowns should be worn when contact of clothing or exposed skin with blood, body fluids, secretions, or excretions is anticipated. Surgical masks and eye protection (goggles or face shield) should be worn during procedures or care activities that may generate splashes or sprays of blood, body fluids, or secretions (eg, during intubation). Masks should also be worn when performing a sterile technique (eg, placement of a central venous catheter [CVC]) to protect patients from exposure to infectious agents present in a health care worker’s nose or mouth. Observations of standard precautions are desirable as adherence may be suboptimal.

VISITOR POLICIES

Although the CDC guidelines did not address the use of PPE (eg, gowns and gloves) by family members visiting their infants, many NICUs are no longer requiring that visitors wear gowns or gloves except for family members of infants in multiple gestations. However, it is critical that hand hygiene be emphasized. The rationale for the use of gowns and gloves for multiple gestations is that if one twin is on contact precautions, for example, for MRSA, visitors could inadvertently transmit MRSA to the other twin unless adhering to contact precautions. Bedside staff are responsible for providing education to family members and observing practice to ensure appropriate use of PPE, including discarding gowns and gloves.

In an era of family-centered care, families, including siblings, are encouraged to visit infants hospitalized in the NICU and sometimes may even participate in care practices. Family-centered care is safe provided there are sound policies to prevent visitors with potentially infectious illnesses from entering the NICU. Thus, no visitors with respiratory tract symptoms, gastrointestinal symptoms, fever, or rash are permitted into the NICU. The challenge of such policies is ensuring compliance, which can be aided by providing written policies to families, signage, and screening tools for staff to administer. Mothers who are infected with potentially transmissible pathogens should not visit their infants until no longer infectious. On a case-by-case basis, mothers who are colonized with MDROs may be able to visit their infants provided they are instructed in effective hand hygiene and the use of gowns and gloves. The department of IP&C must be alerted about such instances and ensure that visitation complies with institutional policies.

Environmental Services

The inanimate health care environment may serve as a reservoir for potential pathogens and has been implicated in transmission.10 HICPAC has published guidelines for disinfection and sterilization in health care facilities.11 Thus, environmental service workers (housekeeping service) are another key group that participates in prevention of HAIs. Adequate training and documentation of effective cleaning and disinfection of environmental surfaces and equipment, including the use of checklists and observations, should be implemented for every NICU. In the NICU, crowding and high rates of device and equipment use can make cleaning challenging.

PREVENTION OF DEVICE-RELATED HAIS

Critically ill neonates often require indwelling devices to meet their ongoing need for nutrition and ventilation. Unfortunately, these necessary support devices may also be portals of entry for microorganisms that cause HAIs. The following sections provide guidelines for prevention of the most common device-related infections in the NICU population. More in-depth discussions of the management of nosocomial infections can be found in Chapter 53.

Central Line-Associated Bloodstream Infections

The CLABSIs contribute to substantial morbidity and potential mortality in the neonate. Very low birth weight (VLBW) infants afflicted by a CLABSI have increased risk for death and neurodevelopmental disability.12 A hospital-acquired bloodstream infection (BSI) may increase both the length of hospital stay and the cost (attributable cost as high as $12,500 per CLABSI).13

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of CLABSIs has been well studied and informs preventive strategies. The most common mechanism of infection results from contamination of the catheter by colonizing skin flora at the insertion site. Infection may also be caused by contamination or colonization of the catheter at the hub, contaminated infusions of fluid or blood products, or hematogenous seeding of the catheter by bacteria from distal sites of infection. Bacterial species, especially coagulase-negative staphylococci (CONS) can adhere to and multiply on synthetic catheter surfaces. Many strains produce a glycocalyx biofilm, which further stimulates adherence to intravascular catheters, as well as protects the organisms from host defense mechanisms and the action of antibiotics.14

The most common pathogens causing CLABSIs are predominantly gram-positive organisms, including CONS, Staphylococcus aureus, and enterococcal species. Escherichia coli and Klebsiella spp. are the most common gram-negative organisms recovered. Rates of CLABSIs caused by fungal pathogens, primarily Candida spp., vary widely across NICUs.15

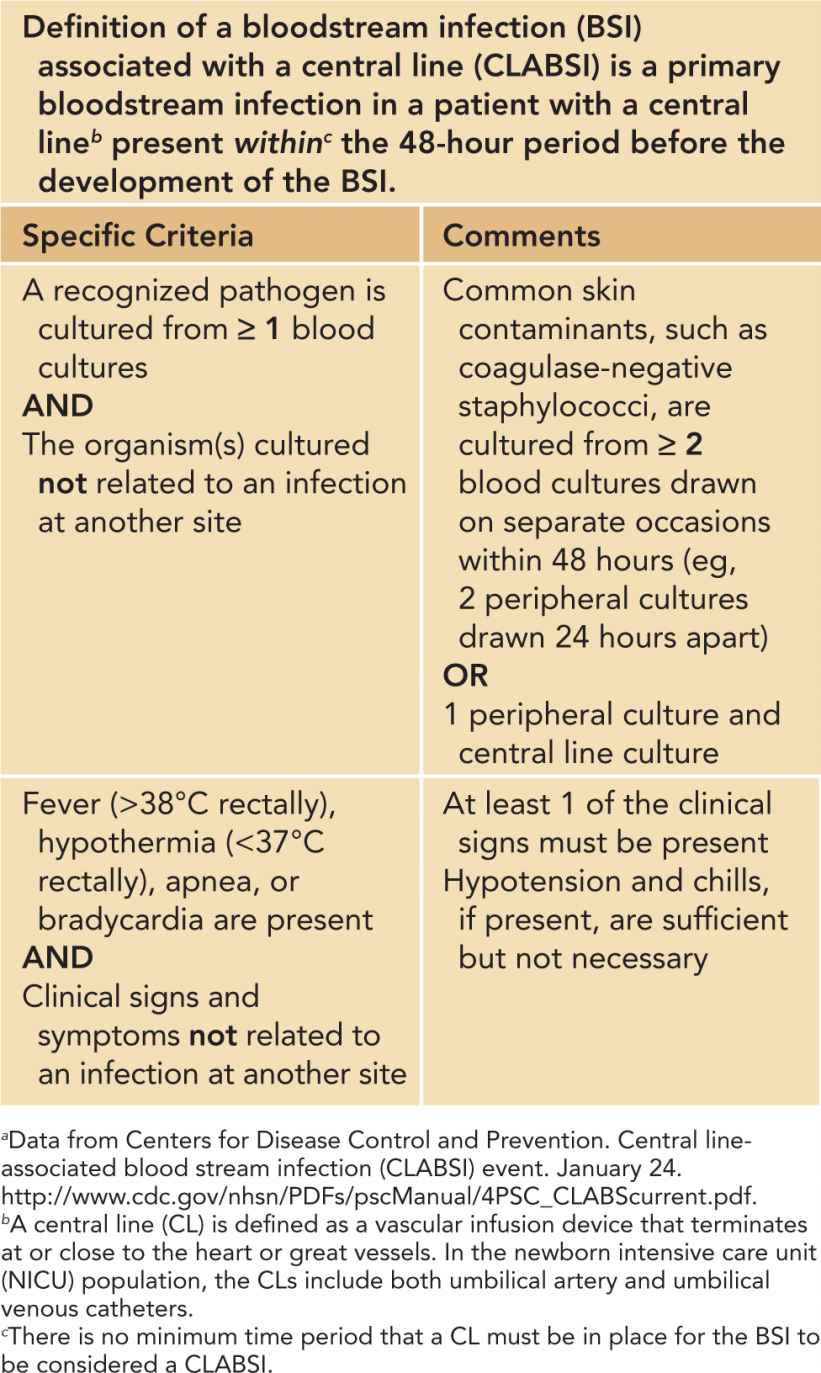

CLABSI Case Definition

Much effort has been put into standardizing case definitions for CLABSIs to ensure interrater reliability, promote accurate rate data, and stratify by risk (ie, birth weight). The NHSN case definition for CLABSIs is shown in Table 6-4. This case definition excludes a single positive blood culture for common contaminants, as positive blood cultures may represent skin flora from inadequately disinfected skin, contamination in the microbiology laboratory, or contamination from inadequately disinfected central line (CL) hubs. It also excludes secondary BSIs that could arise from other types of infections (eg, necrotizing enterocolitis or urosepsis). Notably, more than 2 positive blood cultures are required to define a CLABSI caused by skin flora (eg, Staphylococcus epidermidis). Thus, 2 blood cultures are highly desirable, but achieving an adequate blood volume (ie, 0.5 to 1 mL per bottle) can be challenging in the NICU population.

Table 6-4 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Healthcare Safety Network Case Definition for Central Line-Associated Bloodstream Infectionsa

CLABSI Preventive Strategies

Much effort has focused on methods to prevent CLABSIs. Bundles, defined as evidence-based practices essential for effective and safe patient care that, when implemented together, result in greater improvements in patient outcomes, can reduce the rate of CLABSIs in the NICU population.15,16 Bundled intervention strategies for both insertion and maintenance of CVCs15,17

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree