2Genetic Medicine St Mary’s Hospital, Manchester, UK

3Queen Mary Hospital The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

Overview

- Improvements in our understanding of the aetiology of breast cancer have helped to identify preventive interventions for high-risk women

- A variety of drugs that interfere in the interaction between oestrogen and the oestrogen receptor (selective oestrogen receptor modulators) can reduce breast cancer development when given to high-risk women

- Other drugs, including bisphosphonates, statins, metformin and aspirin, continue to be investigated as preventive agents

- Prophylactic bilateral mastectomy reduces the risk of breast cancer in BRCA mutation carriers by over 90%

- Prophylactic oophorectomy in BRCA mutation carriers reduces the risk of breast cancer by approximately 50%

Screening as currently practised can reduce mortality but not the incidence of breast cancer, and is cost effective only among women for whom breast cancer is common (2–3/1000 per year). Advances in hormonal and cytotoxic treatment and better delivery of care have produced significant survival benefits. A greater appreciation of factors important in the aetiology of breast cancer is to find a preventive intervention for high-risk women. Strategies for breast cancer prevention encompass lifestyle changes as well as surgical and medical therapeutic interventions.

Management Options

The options for a woman at significantly increased risk of breast cancer are limited (Table 6.1). While there is limited evidence that screening such young women is effective in reducing mortality, screening is currently offered to high-risk young women. Many women wish to explore other options to reduce their risk.

Table 6.1 Management options for women at significantly increased risk of breast cancer.

|

Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators (SERMs)

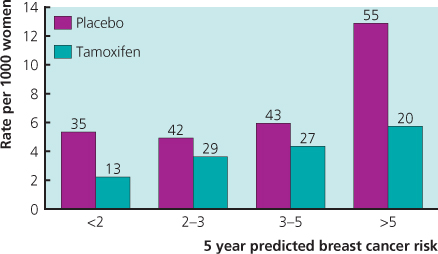

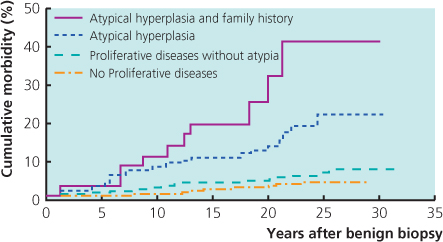

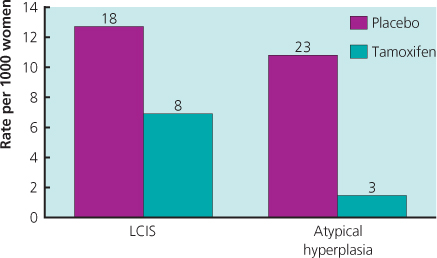

Four large trials with tamoxifen in high-risk women without breast cancer have been undertaken, and long-term follow-up information is now available. An overview of these trials has shown a 43% reduction in ER-positive invasive cancer, but no impact on ER-negative disease. Importantly, a reduced incidence has been seen in the period after active treatment was completed, with an additional 38% reduction in years 6–10. As side effects were minimal in the post-treatment period, the risk–benefit ratio has improved with longer follow-up, and an unanswered question is whether there is additional benefit after 10 years of follow-up. The effectiveness and side-effect profile of tamoxifen are now very well understood (Figure 6.1) and it is currently considered the agent of choice for preventive therapy, especially in premenopausal high-risk women or those with atypical hyperplasia (Figure 6.2) or lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS) (Figure 6.3). See chapter 16.

Figure 6.1 Reduction in invasive breast cancer in the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project tamoxifen breast cancer prevention trial for groups of women with different relative risks of developing breast cancer.

Figure 6.2 Risk of subsequent development of invasive carcinoma in patients with no epithelial proliferation, proliferative disease without atypia (moderate or florid hyperplasia), atypical hyperplasia or atypical hyperplasia and a family history of cancer.

Figure 6.3 Reduction in invasive breast cancer observed in the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project tamoxifen breast cancer prevention trial for women with a prior diagnosis of lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS) and atypical hyperplasia. Diagnosis was based entirely on patient history. Neither the histology report nor the previous histology slides were reviewed.

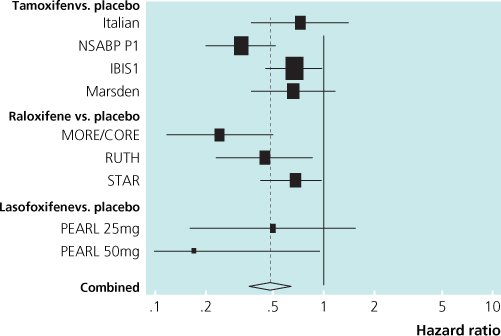

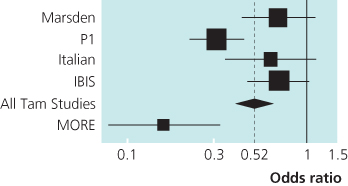

Another SERM, raloxifene, has been evaluated in three randomised trials. In two of these trials breast cancer was not the primary endpoint, but nevertheless the results showed a marked decrease in breast cancer incidence with raloxifene. Early reports suggested a greater benefit than tamoxifen (Figure 6.4). The most recent direct comparison with tamoxifen in the STAR trial at 81 months indicated that the risk ratio of raloxifene:tamoxifen was 1.24 for invasive cancer and 1.22 for non-invasive disease. Adverse events were less common with raloxifene: RR 0.55 for endometrial cancer; RR 0.19 for endometrial hyperplasia; and RR 0.75 for thromboembolic events. Raloxifene for postmenopausal women thus appears to have advantages compared with tamoxifen (Figure 6.5).

Figure 6.4 Incidence of ER-positive invasive breast cancer in the prevention trials with tamoxifen or raloxifene.

Figure 6.5 Overview of prevention trials showing reduction in incidence of oestrogen receptor-positive invasive breast cancer by tamoxifen and raloxifene.

IBIS = International Breast Intervention Study 1

Italian = Italian Study

Marsden = the Royal Marsden Trial

MORE = Multiple Outcomes of Raloxifene study

P1 = National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project P1 Study

All studies used tamoxifen except the MORE trial that used raloxifene.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree