Premenstrual Syndrome

Robert L. Reid

Molimina, Premenstrual Syndrome, and Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder

During the reproductive years, up to 80% to 90% of menstruating women will experience symptoms (breast pain, bloating, acne, constipation) that forewarn them of impending menstruation, so-called premenstrual molimina. Available data suggest that as many as 30% to 40% of these women are sufficiently bothered by such molimina that they would seek relief if it were readily accessible, simple, and safe. Since the term premenstrual syndrome (PMS) has become so ingrained in lay culture, most women describe the symptoms of molimina as PMS. However, moliminal symptoms show a variable association with the more severe psychologic symptoms typically required to meet the research diagnostic criteria for PMS.

Researchers in the field have argued that the term premenstrual syndrome should be reserved for a more severe constellation of symptoms that affects closer to 5% of women during their reproductive years. To capture the true severity of PMS in this population, the definition describes not only the symptoms but also their functional impact. PMS has been defined as “the cyclic recurrence in the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle of a combination of distressing physical, psychological, and/or behavioral changes of sufficient severity to result in deterioration of interpersonal relationships and/or interference with normal activities.”

The American Psychiatric Association, following years of debate about whether to include PMS in their Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV), included as an appendix (meaning that the subject requires further study) a condition labeled premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) (Table 38.1). Such a designation was intended to alert physicians to a combination of specific severe symptoms (mostly psychiatric in nature) that could mimic other psychiatric disorders with the exception that the symptoms recurred in the premenstrual phase of the menstrual cycle.

Diagnosis

History and Charting

A typical woman suffering from PMS may describe herself as a well-adjusted person for most of the month who is productive at work and in other endeavors and, if she has children, a good mother. However, starting 7 to 10 days prior to menstruation, she awakes in the morning with feelings of anger, anxiety, or sadness. At work, she may have difficulty concentrating on the tasks at hand and may overreact to otherwise typical actions of coworkers, friends, her partner, or her children. She feels depressed but cannot understand why because she typically enjoys life and is happy with most of its aspects. Occasionally, depression, anger and aggression, or anxiety may be extreme and result in concerns for the welfare of the affected woman or those around her.

A “black and white” diagnostic cutoff for determining if someone suffers from PMS is not presently possible. Although many women report feeling bloated and irritable before menstruation, further questioning usually reveals that these symptoms have little substantive impact on their lives.

In part, the distinction between troublesome premenstrual moliminal symptoms and PMS may have to do with the duration and severity of symptoms. Particularly in the first few years after symptoms appear, the severity of PMS

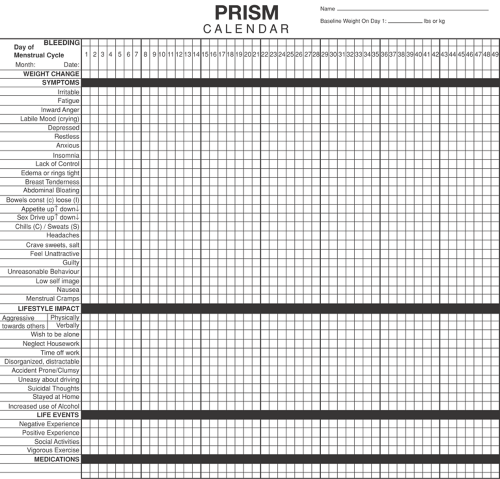

may vary dramatically from month to month. The nature of symptoms and their functional impact is best established by self-report using a prospective calendar record. Any calendar used for this purpose must obtain information on four key areas: specific symptoms, severity, timing in relation to the menstrual cycle, and baseline level of symptoms in the follicular phase.

may vary dramatically from month to month. The nature of symptoms and their functional impact is best established by self-report using a prospective calendar record. Any calendar used for this purpose must obtain information on four key areas: specific symptoms, severity, timing in relation to the menstrual cycle, and baseline level of symptoms in the follicular phase.

TABLE 38.1 Diagnostic Criteria for Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Retrospective accounts about symptoms often fail to provide critical information on timing of symptoms or baseline level of symptoms during the follicular phase of the cycle. For example, many individuals with underlying psychiatric disease will experience premenstrual exacerbation of their symptoms. They will recall the severe symptoms prior to menstruation and may give a history that sounds typical for PMS. However, when they complete a 2-month calendar record, it usually becomes apparent that symptoms are present all the time and are at their worst premenstrually. This has been termed premenstrual magnification of an underlying psychiatric disorder.

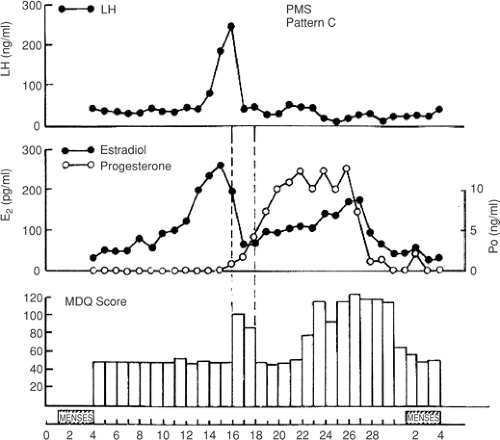

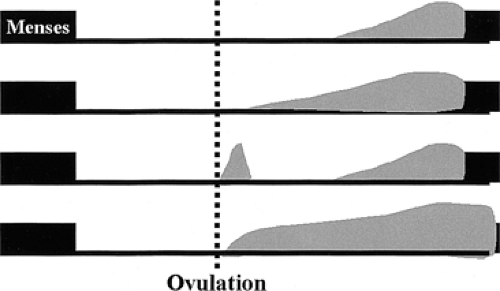

PMS symptoms typically appear after ovulation, worsen progressively leading up to menstruation, and are relieved at varying rates after the onset of menstruation. In some women, there is almost immediate relief from any psychiatric symptoms with the onset of bleeding, while for others the return to normal is more gradual. The most severely affected women report symptoms beginning shortly after ovulation (2 weeks before menstruation) and resolving at the end of menstruation. Such individuals typically report having only one “good week” per month. If this pattern is long standing, then it becomes increasingly difficult for interpersonal relationships to rebound during the good week with the result that symptoms may start to take on the appearance of a chronic mood disorder. Whenever charting leaves the diagnosis in doubt, a 3-month trial of medical ovarian suppression (discussed later in the chapter) usually will provide a definitive answer.

About 5% to 10% of women who suffer from PMS experience a brief burst of symptoms (coincident with the midcycle fall in estradiol that accompanies ovulation) with a return to normal later in the luteal phase when symptoms recur (Fig. 38.1). The different patterns of PMS symptoms are shown in Figure 38.2.

Information should be sought about stresses related to the woman’s occupation and personal life, as these may tend to exacerbate PMS. Past medical and psychiatric diagnoses may be relevant in that a variety of medical and psychiatric disorders may show premenstrual exacerbation. A prospective symptom record should usually be maintained for a minimum of two complete cycles prior to establishing a diagnosis, since an unfavorable life event occurring during the follicular phase of a single month could give the erroneous impression that symptoms were continuously present. Key components of a prospective symptom record are listed in Table 38.2.

One example of such a calendar record, the PRISM calendar (prospective record of the impact and severity of menstrual symptoms) (Fig. 38.3) allows rapid visual confirmation of the nature, timing, and severity of menstrual cycle–related symptomatology and at the same time provides information on life stressors and the use of PMS therapies. Although symptoms are rated in severity on a scale from 1 to 3, the actual interpretation of the calendar requires no mathematical calculations. An arm’s length assessment of the month-long calendar usually allows a rapid distinction to be made between PMS and other more chronic conditions (Fig. 38.4).

Physical Findings

History should usually be accompanied by a physical and gynecologic exam, since many women with apparent PMS may have coexisting medical conditions. The summation of premenstrual and menstrual symptoms often determines the overall experience of women who suffer from PMS, and therapy directed at gynecologic disorders such as dysmenorrhea or heavy flow can dramatically reduce the perceived severity of menstrual-related symptoms. Organic causes of PMS-like symptoms must be ruled out. Marked fatigue may result from anemia, leukemia, hypothyroidism, or

diuretic-induced potassium deficiency. Headaches may be due to intracranial lesions. Women attending PMS clinics have been found to have brain tumors, anemia, leukemia, thyroid dysfunction, gastrointestinal disorders, pelvic tumors including endometriosis, and other recurrent premenstrual phenomena such as arthritis, asthma, epilepsy, and pneumothorax. Efforts to rule out such causes for premenstrual distress are important before choosing any PMS therapy.

diuretic-induced potassium deficiency. Headaches may be due to intracranial lesions. Women attending PMS clinics have been found to have brain tumors, anemia, leukemia, thyroid dysfunction, gastrointestinal disorders, pelvic tumors including endometriosis, and other recurrent premenstrual phenomena such as arthritis, asthma, epilepsy, and pneumothorax. Efforts to rule out such causes for premenstrual distress are important before choosing any PMS therapy.

Blood Tests

Contrary to some claims, there is no blood test that will establish a diagnosis of PMS. Blood work is only helpful to rule out conditions such as anemia, leukemia, or thyroid dysfunction.

Etiology

Many theories have attempted to explain the diverse manifestations of PMS, but until recently, no single theory has received widespread acceptance. Many of the early theories lacked biologic plausibility and appeared to have emerged as a means to market specific therapeutic products. More recently, a theory that links gonadal steroid levels and central serotonergic activity has begun to emerge.

The current consensus seems to be that in some predisposed women, normal fluctuations in the gonadal hormones estrogen and progesterone trigger central

biochemical events related to PMS symptomatology. Of all the neurotransmitters studied to date, serotonin seems to be the most promising central target. It is likely that serotonin levels dip premenstrually in most women and that susceptible individuals will show varying degrees of psychiatric symptomatology. Many women report a menstrual or immediate postmenstrual state of mental well-being (sometimes bordering on euphoria) that may reflect a rebound surge of serotonin activity. The theoretical effects of gonadal hormones on serotonin activity (Fig. 38.5) form the basis for several current interventions for PMS and PMDD.

biochemical events related to PMS symptomatology. Of all the neurotransmitters studied to date, serotonin seems to be the most promising central target. It is likely that serotonin levels dip premenstrually in most women and that susceptible individuals will show varying degrees of psychiatric symptomatology. Many women report a menstrual or immediate postmenstrual state of mental well-being (sometimes bordering on euphoria) that may reflect a rebound surge of serotonin activity. The theoretical effects of gonadal hormones on serotonin activity (Fig. 38.5) form the basis for several current interventions for PMS and PMDD.

TABLE 38.2 Key Elements of a Prospective Symptom Record Used for the Diagnosis of Premenstrual Syndrome | |

|---|---|

|