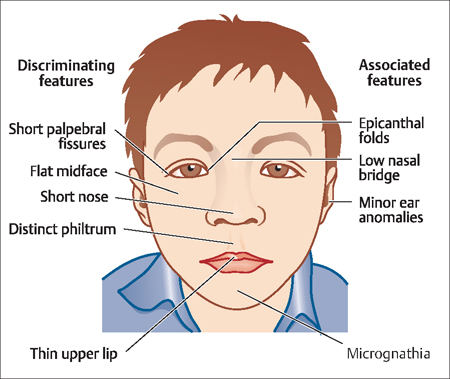

9 Preconception and Antepartum Care Gustavo F. Leguizamón Preconception and antepartum care are excellent examples of effective primary prevention. Because more than 50% of pregnancies in the United States are unplanned, health care providers should advise every woman in her reproductive years to seek preconception care and counseling. This chapter offers an overview of the key components of effective preconception and antepartum care, and refers the reader to other chapters for more detailed descriptions of specific approaches and procedures. Preconception care: Preconception care is a set of interventions that identify and modify biomedical, behavioral, and social risks to a woman’s health prior to her conceiving a child. It includes both prevention and management, emphasizing health issues that require action before conception, or very early in pregnancy, for maximal impact. The target population for preconception care is women of reproductive age, although men are also targeted by several components of preconception care. Antepartum care: The antepartum period refers to events occurring or existing after conception and before birth. This is also known as the “prenatal” period. So, antepartum care has the dual goals of ensuring a healthy baby and a healthy mother. Antepartum care includes the evaluation of the health status of both mother and fetus, estimation of the gestational age of the baby, identification of the patient at risk for complications, anticipation of problems before they occur (and prevention, if possible), and patient education and communication. Primary prevention consists of intervening before pathological changes have begun, to prevent the occurrence of disease. Preconception care is an excellent example of how primary prevention methods and the identification/ modification of risk factors can markedly improve pregnancy outcomes, particularly for women with chronic diseases such as diabetes, hypothyroidism, and substance abuse issues. Because more than 50% of the pregnancies in the United States are unplanned, health care providers should advise every woman in her reproductive years to seek preconception care and counseling. Indeed, an overwhelming amount of evidence suggests the best time to evaluate, counsel, and potentially treat specific conditions affecting pregnancy is before conception. There are four critical areas for determining risks and implementing interventions during the preconception period: The most relevant variables to determine are maternal age and life-style factors as well as the presence of previously existing conditions, such as infections or chronic disease. How these factors impact preconception care is described below. Extremes of reproductive years are of special concern. The pregnant teenager is at increased risk for sexually transmitted diseases, and requires special attention paid to issues such as nutrition and emotional support. Mothers older than 35 years present an increased risk for chromosomal abnormalities, such as Down syndrome, which lead to a significant increase in the risk for spontaneous abortion as well as major congenital anomalies. Timely education would most likely increase the opportunity to prevent teenage pregnancy and help women to make decisions regarding the age of conception. Finally, advanced paternal age is associated with increased genetic risk to the fetus and is considered when the father is older than 55 years. Tobacco: Smoking is a well-known, modifable risk factor. It has been associated with increase risk for spontaneous abortion, prematurity, intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), premature rupture of membranes (PROM), abruptio placentae, and placenta previa. Of significant clinical importance is the fact that smoking discontinuation before or during early pregnancy reduces these tobacco-associated risks. Alcohol: Drinking alcohol has been clearly identified as a risk factor for adverse pregnancy outcome. There is also strong evidence that harm can occur early in gestation, even before the patient is aware of her pregnancy. The so-called “fetal alcohol syndrome” (FAS) is defined by the presence at least one of the following signs: When these findings are associated with maternal alcohol consumption during pregnancy, the diagnosis is confirmed. In addition to growth and neurological deficits, children with FAS tend to have distinctive facial anomalies (Fig. 9.1), making it particularly difficult for them to adjust socially. Thus, it is truly a devastating condition for a child, and would-be mothers should be made fully aware of the potential consequences of drinking alcohol on the developing fetus. When taking the medical history, four specific questions, which are often referred to as TACE (Tolerance, Annoyed, Cut down, and Eye opener), will help to identify women at risk for alcohol-related fetal complications (Table 9.1). Since alcohol-related fetal complications can be completely prevented by stopping alcohol consumption before conception, all women seeking preconception care should be advised to do so. Fig. 9.1 Facial anomalies in young children are among the discriminating characteristics of fetal alcohol syndrome

Definitions

Preconception Care

History

Maternal Age

Life-Style Factors

| T (tolerance) | How many drinks does it take to make you feel high (can you hold?) |

| A (annoyed) | Have people annoyed you by criticizing your drinking? |

| C (cut down) | Have you felt you ought to cut down on your drinking? |

| E (eye opener) | Have you ever had to drink first thing in the morning to steady your nerves or to get rid of a hangover? |

Source: Sokol RJ, Martier SS, Ager JW: The TACE questions Practical prenatal detection of risk-drinking Am J Obstet Gynecol 1989;160:863

Prescription drugs: Millions of women of childbearing age receive prescriptions for potentially teratogenic class D and X medications each year (Table 9.2). The most often prescribed potentially teratogenic prescription drugs are anxiolytics, anticonvulsants, statins, and certain antibiotics. Therefore, physicians should ascertain whether a woman is taking any of them in early gestation. Because the indications for clinical use, as well as the risk of an adverse birth outcome, vary significantly among medications classifed as class D or X, it is important for clinicians to counsel women about potential risks and benefits as well as about planning the timing of conception.

| Medication class | Annual prescriptions for class D or X* drugs, in millions (95% CI) | Proportion of prescriptions for class D or X* drugs |

| Anxiolytics | 4.06(3.88–4.23) | 35% |

| Alprazolam | 1.46 | |

| Clonazepam | 0.99 | |

| Lorazepam | 0.76 | |

| Diazepam | 0.69 | |

| Temazepam | 0.12 | |

| Chlordiazepoxide | 0.03 | |

| Anticonvulsants | 1.42.(1.33–1.51) | 12% |

| Divalproex sodium | 0.71 | |

| Carbamazepine | 0.44 | |

| Phenytoin | 0.18 | |

| Valproate | 0.05 | |

| Phenobarbital | 0.04 | |

| Primidone | 0.01 | |

| Antibiotics | 1.38 (1.29–1.47) | 12% |

| Doxycycline | 0.90 | |

| Tetracycline | 0.38 | |

| Tobramycin | 0.10 | |

| Statins | 0.76 (0.69–0.83) | 6% |

| Atorvastatin | 0.45 | |

| Pravastatin | 0.16 | |

| Simvastatin | 0.11 | |

| Fluvastatin | 0.02 | |

| Lovastatin | 0.01 | |

| Isotretinoin | 0.54 (0.49–0.59) | 5% |