Features of cytologic atypia

1. Loss of nuclear polarity

2. Irregular nuclear shape

3. Irregular nuclear contours

4. Vesicular chromatin

5. Hyperchromatic chromatin

6. Prominent nucleoli

Reclassification of hyperplastic endometria from the WHO 1994 system to the EIN system (which aligns with the current WHO 2014 classification) has been studied [7]. Reclassification of WHO 1994 cases using the four-tiered system of hyperplasia with and without atypia using strict EIN (WHO 2014) criteria demonstrated that the majority of cases considered complex atypical hyperplasia comprise the EIN/AH group. Interestingly, 44 % of cases of complex, non-atypical and 4 % of cases of simple, non-atypical hyperplasia were reclassified as EIN/AH [7]. This comes as little surprise as many pathologists have had difficulty with vexing cases of non-atypical hyperplasia that are worrisome, but not diagnostic of atypical hyperplasia. The utilization of cytologic demarcation in the EIN/AH system will help to alleviate this issue.

Background: Morphometry to Subjective Practice

In the late 1970s, advances in computer hardware and software allowed for computerized morphometric analysis of pathologic samples. These techniques were applied to endometrial samples in the hopes of identifying more objective methods for evaluation of precancerous lesions [8–11]. As these methods were refined and correlated with outcome, specific architectural [12] and cytologic [13, 14] features were identified that could predict patients predisposed to carcinoma. Combinations of measurable architectural and cytologic features as well as the volume percentage of stroma present in the samples were measured and used to calculate a D-score (Table 7.2) [15]. Cases that were subjected to computerized morphometry were reliably classified into probable precancer (EIN), unknown, and probable benign categories with relative success; however, the requirements for resources and technical expertise to carry out this methodology were great, limiting its adaptation outside of a few large reference centers. Through the efforts in developing computerized morphometry, evaluation of volume percent stroma as a keystone of precancer identification was realized, and this determination became one of the key histologic features utilized when making a diagnosis of EIN/AH.

Table 7.2

Measurements taken to determine D-score

Components of D-score |

|---|

1. Volume percent stroma |

2. Standard deviation of the shortest nuclear axis |

3. Gland outer surface density |

Another key component of the WHO 2014 EIN/AH classification is cytologic demarcation. This premise differs from the identification of cytologic atypia in that it is a comparison of clonal vs. non-clonal glands within the same specimen. Initially this association was described in patients with endometrial carcinoma. It was noted that adjacent to the carcinoma there were monoclonal populations of endometrial glands which were histologically different from the patient’s native endometrium [16]. These precancerous glands formed the histologic basis for the EIN/AH schema which is in place today. Volume percent stroma and cytologic demarcation from these early studies were combined with size cutoffs and exclusion of mimics to create the EIN classification system, which as a result, represents a histologic descriptor of underlying genetic mutations [17].

EIN/AH and Cancer Risk

Studies of patients with a diagnosis of EIN/AH have shown that the WHO 2014 system is more effective at predicting patients that will progress to, or concurrently have, endometrial carcinoma [18]. A patient with a new diagnosis of EIN/AH will suffer from occult, concurrent carcinoma (defined as a cancer diagnosis in 1 year) in one-third of cases [19]. Patients that do not develop adenocarcinoma in the first year have been found to carry a 45-fold increase in risk of progression to low-grade endometrioid carcinoma compared to those with non-atypical hyperplasia [20]. While these quoted figures are striking, the exact percentage of patients that might progress to adenocarcinoma is impossible to determine, as many patients are definitively treated with hysterectomy at the time of diagnosis of EIN/AH; however, these are comparable with those reported for the previous WHO 1994 classification [21, 22].

Endometrial Carcinoma Is Derived from EIN/AH

Central to the theory of precancerous lesions is the idea that carcinomas can be directly linked to their putative precursors. Progressive microsatellite changes in precancerous and cancerous endometrium have demonstrated a direct link between nonfamilial, precancerous endometrium, and adjacent endometrial carcinomas [23]. Subsequently, microsatellite allotype mapping has shown that endometrial precancers (histologically EIN/AH) develop into endometrial adenocarcinoma, and that additional mutations can lead to intratumoral genetic heterogeneity in various regions of the tumor that could lead to tumor progression [24]. These elegant studies support the idea that tumor progression occurs through physical extension of clonal lesions, i.e., endometrial precancers.

EIN/AH Differs from Normal Endometrium

Normal endometrial glands represent a polyclonal population of tissue from which monoclonal precursor lesions arise. Indeed, EIN/AH represents a novel population of monoclonal glands that are genetically and histologically distinct from the background native endometrium [16, 25]. As previously mentioned, subsets of these lesions have microsatellite instability which has been mapped to show direct continuity between histologically identifiable precancers and their adjacent tumors [23]. While these mutations set EIN/AH apart from normal endometrium, they do not convey the ability to invade or metastasize, which also sets them apart from endometrial adenocarcinoma.

EIN/AH Shares Genetic and Phenotypic Features with Endometrial Carcinoma

Cells undergoing transformation from benign to precancerous harbor genetic mutations that confer growth advantages and set them apart from normal background endometrium. These same mutations also link these cells to the subsequent adenocarcinomas. Studies have repeatedly demonstrated that EIN/AH and adenocarcinoma contains similar, nonrandom X-chromosome inactivation as well as specific, conserved microsatellite mutations in lesions within individuals [23–27]. Further supporting evidence has been described involving single-gene mutations that are known to be associated with endometrioid endometrial adenocarcinoma. Studies have identified inactivation of PTEN [28–30], PAX2 [31], mutations in K-RAS [32–34], and hypermethylation of hMLH1 [35] in precancerous endometrial lesions. In fact, PTEN and PAX2 mutations are such common events in EIN/AH that immunohistochemical staining has been suggested as a diagnostic adjunct in difficult cases (described later).

EIN/AH Can Be Diagnosed

The synthesis of the years of scientific exploration into the roots of endometrial carcinogenesis has led to the development of the benign hyperplasia/EIN sequence [36]. This sequence outlines specific histologic features that can reliably be identified by routine light microscopy. Furthermore, these features can reliably identify glandular proliferations as precancerous. The acceptance of this diagnostic schema has culminated in its adoption by the WHO as the formal classification system for endometrial precancers [1].

Endometrial Hyperplasia without Atypia

Endometrial hyperplasia without atypia (benign hyperplasia) is most commonly seen in perimenopausal women with symptoms of abnormal uterine bleeding, but can occur in any woman with a systemic and unopposed excess of estrogen. The etiologic differential diagnosis for elevated estrogen not counterbalanced by progesterone is broad and includes chronic anovulation, hormone replacement, or estrogen-secreting ovarian tumors. Depending on the duration of unopposed estrogen on the endometrium, architectural changes range from a predominantly normal proliferative pattern with occasional cystically dilated glands (disordered proliferative endometrium) to progressive gland crowding with gland branching and dilation (the so-called benign hyperplasia sequence ). According to the 2014 WHO Classification of Tumors of the Female Reproductive Organs, the new diagnostic term “endometrial hyperplasia without atypia” encompasses the 1994 WHO classification terms of “simple hyperplasia without atypia” and “complex hyperplasia without atypia” [1, 36, 37].

The earliest histologic changes of unopposed estrogen are collectively referred as “disordered proliferative endometrium .” Most importantly, the endometrium shows a normal gland-to-stroma ratio. Isolated dilated glands are interspersed in a background of a mitotically active proliferative pattern endometrium (Fig. 7.1). Additionally, tubal metaplasia may accompany these changes. In contrast to the preserved normal gland-to-stroma ratio in a disordered proliferative pattern, continuous unopposed estrogen results in a global increase in the gland-to-stroma ratio (hyperplasia). Best appreciated on low-power examination, the hyperplastic endometrium shows a “regularly irregular” pattern; normal proliferative glands are admixed with more crowded branching or dilated glands (Fig. 7.2). Of note, the cytologic features of the glands are unchanged from field to field. Nuclei are “pencil shaped” and demonstrate an orderly columnar arrangement with respect to the basement membrane (Fig. 7.3). Mitotic figures are present, but not overly abundant nor atypical. Stromal hemorrhage and breakdown as well as reparative epithelial changes are not uncommon [1, 17, 37]. A monoclonal precancerous lesion or frank carcinoma is notably absent. Prolonged and unopposed estrogen exposure carries a two- to tenfold risk of endometrial carcinoma [38–40]. In a long-term follow-up study by Kurman et al., progression to carcinoma was seen in 1 % (simple hyperplasia) and 3 % (complex hyperplasia) of “untreated” patients with endometrial hyperplasia without atypia [41]. Treatment of endometrial hyperplasia without atypia centers on hormonal therapy or elimination of the cause of estrogen excess (e.g., weight loss in case of obesity).

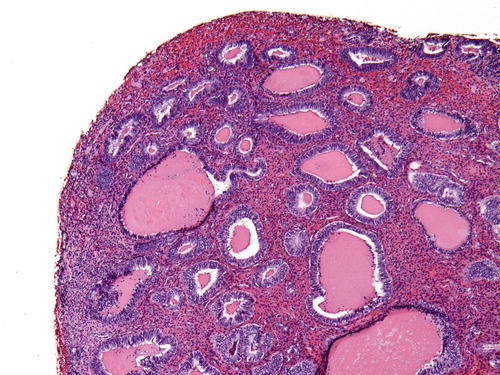

Fig. 7.1

Disordered proliferative endometrium displaying an admixture of normal and cystically dilated glands

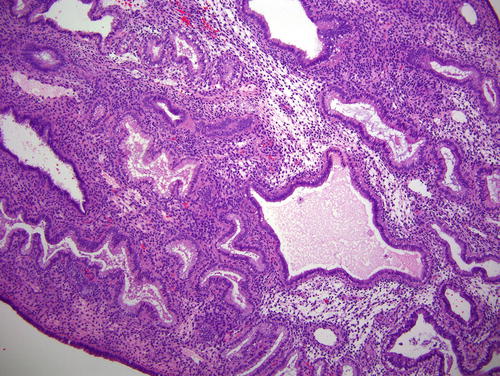

Fig. 7.2

Hyperplasia without atypia (low power) comprised of a population of slightly crowded glands and intervening stroma. Note the presence of a few microcysts, indicative of a chronic anovulatory state

Fig. 7.3

Hyperplasia without atypia (high power) demonstrating crowded glands with bland nuclei

Endometrial Intraepithelial Neoplasia/Atypical Hyperplasia

Endometrioid intraepithelial neoplasia/atypical hyperplasia (EIN/AH) has recently been adapted by the 2014 WHO Classification of Tumors of the Female Reproductive Organs as the standard terminology for precancerous endometrial lesions, essentially eliminating the usage of the 1994 WHO terms of simple atypical hyperplasia and complex atypical hyperplasia [1, 37]. This paradigm shift occurred due to evidence that (1) the 1994 WHO classification scheme suboptimally risk stratified patients according to the biology of the disease and (2) diagnoses relied heavily on assessment of cytologic atypia which was found to be poorly reproducible, even among experts [3, 15, 18, 36, 42–44]. While histologic overlap exists, there is no direct diagnostic correlation between the 1994 WHO classification and the 2014 EIN/AH scheme (e.g., the terms complex atypical hyperplasia and EIN should not be used interchangeably). EIN/AH represents a distinct monoclonal precancerous lesion to endometrioid (type I) endometrial carcinoma (Table 7.3).

Table 7.3

Summary of clinical and diagnostic parameters of hyperplasia without atypia and EIN/AH

2014 WHO | 1994 WHO | Origin | Histology | Genetics | Treatment | Risk |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Hyperplasia without atypia | Simple hyperplasia without atypia Complex hyperplasia without atypia | Excess estrogen (anovulatory cycles, polycystic ovarian syndrome, obesity, estrogen-producing tumor) | “Regularly irregular” pattern Diffuse endometrial involvement Crowded proliferative glands with branching and dilation; no cytologic demarcation | Polyclonal | Hormonal therapy | Two- to tenfold risk of developing endometrial carcinoma in the future |

EIN/AH | Simple hyperplasia with atypia Complex hyperplasia with atypia | Endometrial Precan cer | Focal or diffuse endometrial involvement Gland crowding (VPS < 55 %) Cytologic demarcation Size: >1 mm Exclusion of benign mimic and carcinoma | Monoclonal | Hormonal therapy or surgery (hysterectomy) | 33–41 % risk of concurrent endometrial carcinoma 45-fold increased risk to develop endometrial carcinoma within 1 year |

The diagnostic criteria for EIN/AH are fourfold and include architectural gland crowding (VPS < 55 %), cytologic demarcation of the lesional focus from background endometrium, size of more than 1 mm (one-half of a 10× field is a helpful guide), and exclusion of benign mimics and carcinoma (Table 7.4). All of these criteria must be met for a diagnosis of EIN/AH (Fig. 7.4). Gland crowding , whether focal or diffuse, is best assessed at low-power magnification, and as stated, the proportion of endometrial glands should be greater than 1:1. While crowded, glands are still separated by stroma, a crucial distinguishing characteristic between EIN/AH and endometrioid carcinoma. Lesional glands appear tubular or dilated and branching. As one moves from the epicenter of the focus of crowded glands, the clonal gland population will become slightly less crowded, and interspersed normal glands may be identified (Fig. 7.5). Of course, this pattern of glandular crowding is predicated on having a relatively intact fragment of tissue to examine.

Table 7.4

EIN/AH diagnostic criteria

Diagnostic criteria for EIN/AH (all must be met for the diagnosis) |

|---|

Gland crowding (VPS < 55 %) |

Cytologic demarcation from background endometrium |

Size: at least 1 mm |

Exclusion of benign mimics and carcinoma |

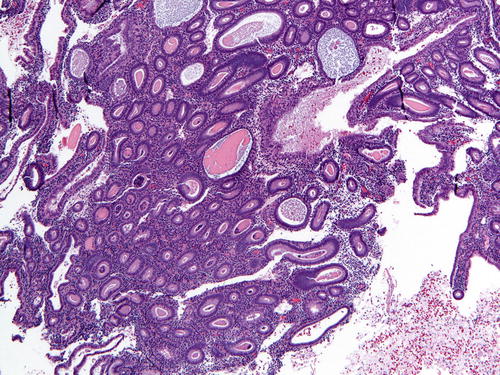

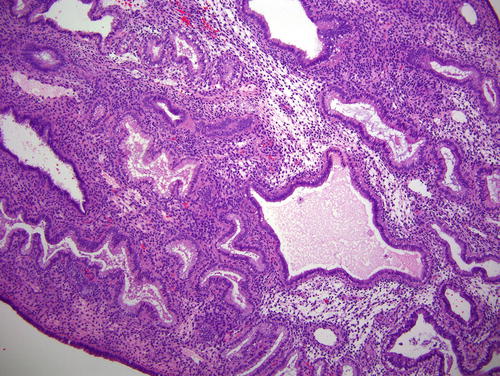

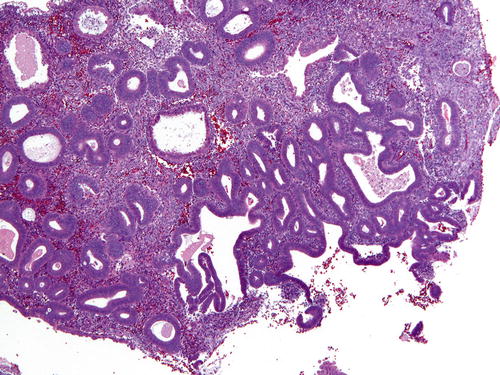

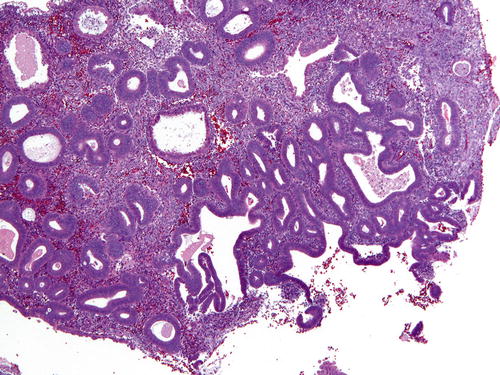

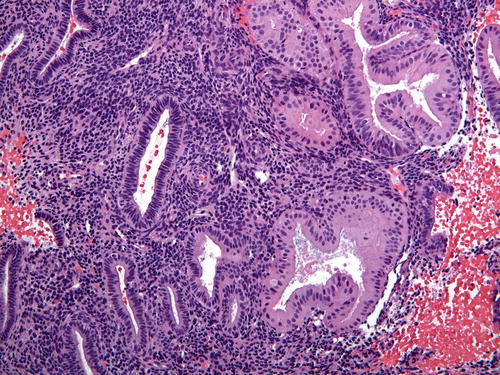

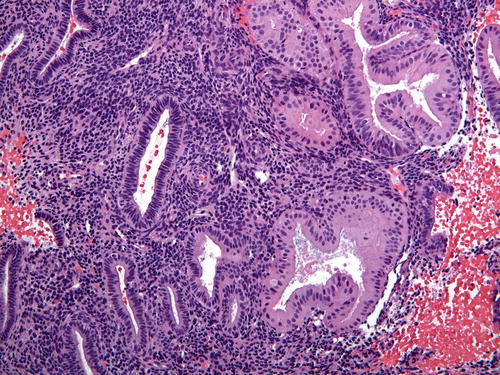

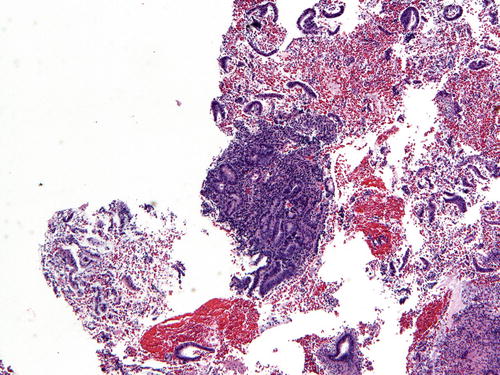

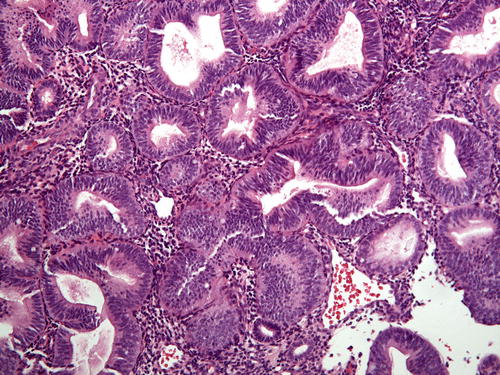

Fig. 7.4

EIN/AH denoted by the presence of crowded glands that differ from the background endometrium. In this figure the EIN/AH is lighter in staining intensity than the background endometrial glands (center), but does not display generally acceptable atypical nuclear features

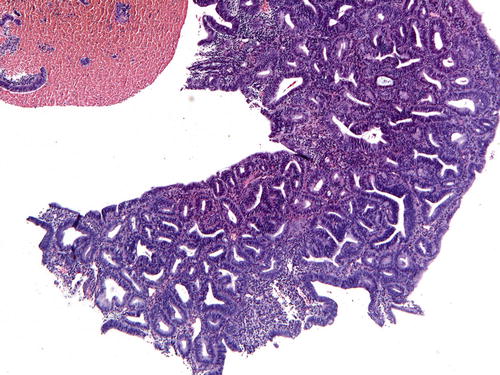

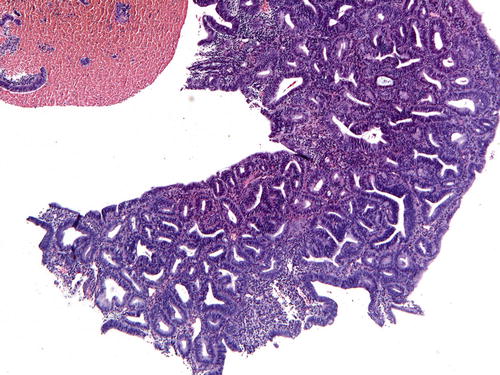

Fig. 7.5

A low-power view of gland crowding in which anovulatory glands compose slightly more than half of the tissue in the demonstrated field

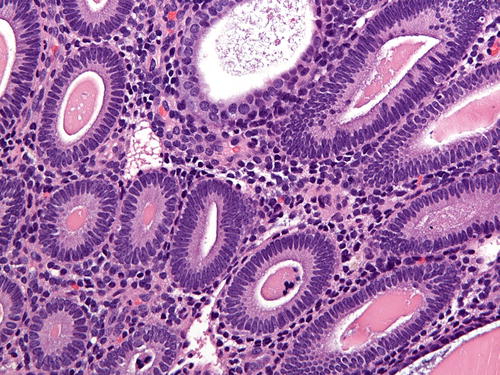

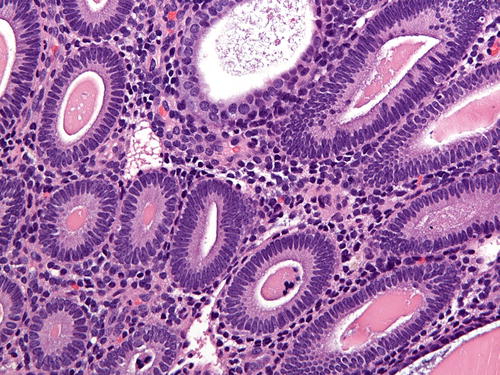

One of the central tenants of EIN/AH is cytologic demarcation. Lesional glands must display altered cytology (difference in nuclear and/or cytoplasmic features) compared to the background endometrium (Fig. 7.6). The cytologic features of EIN/AH vary widely and are predominantly dependent on the hormonal environment. For example, nuclei may be cigar shaped, pseudostratified, or rounded with prominent nucleoli. The cytoplasm may demonstrate typical endometrioid morphology or show altered differentiation (e.g., secretory, mucinous, eosinophilic) (Fig. 7.7). As such, the criteria for classical atypia (rounded nuclei, vesicular chromatin, prominent nucleoli, anisonucleosis, loss of polarity) are not a requirement; rather, it is the comparison to the background endometrium that establishes whether the criterion for cytologic demarcation is met.

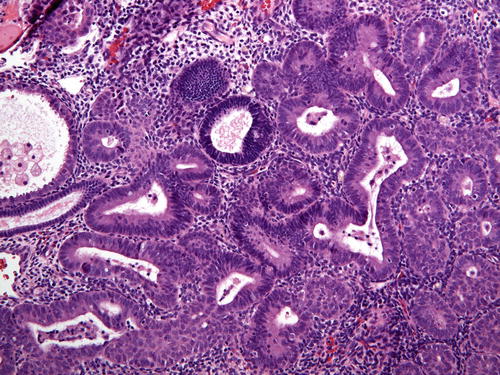

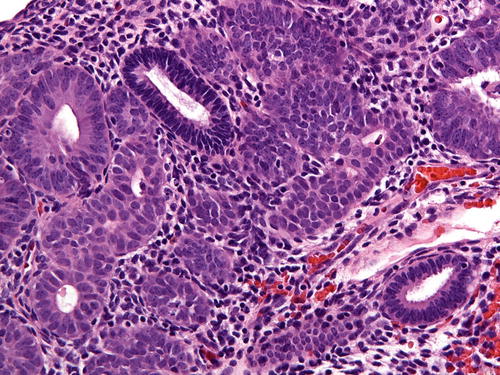

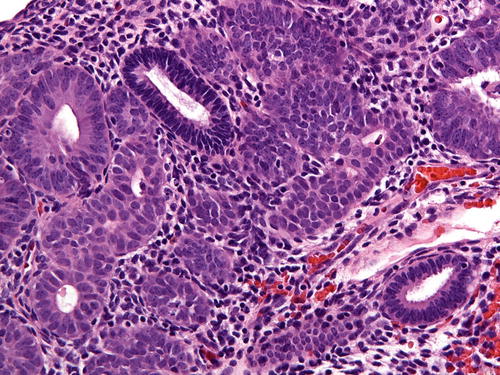

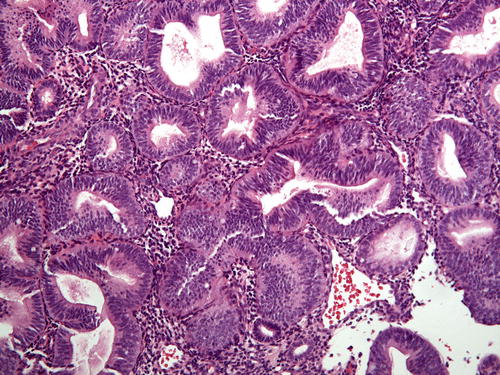

Fig. 7.6

Cytologic demarcation can be easily identified in this image. Normal glands stain much darker and are surrounded by crowded glands with altered cytology; here, the cells have more rounded nuclei with nucleoli

Fig. 7.7

In this example of cytologic demarcation, the EIN/AH is composed of enlarged cells with ample eosinophilic cytoplasm. Note that the nuclei are not significantly “atypical”

At minimum, the requirement for size of EIN/AH is 1 mm measured in a single dimension. Of note, multiple foci are not additive. This 1 mm cutoff is historically based in the morphometric studies used to evaluate volume percent stroma in precancerous lesions. Adhering to a minimum size of 1 mm prevents overcalling of small areas of compressed glands as well as other potentially subdiagnostic or artifactual lesions. Lesions that are smaller than 1 mm, yet felt to be cytologically altered and crowded, are best classified as “focal gland crowding ” (discussed later).

Before rendering a diagnosis of EIN/AH, benign mimics and carcinoma must be excluded. Examples of the former include but are not limited to artificial gland crowding, telescoping of glands, hyperplasia without atypia, endometrial polyps, endometrium with reparative change or tubal metaplasia, and fragments of normal lower uterine segment. When glandular growth shows a back-to-back cribriforming pattern without intervening stroma, villoglandular, mazelike, or solid growth, the diagnosis of endometrioid adenocarcinoma is warranted (Fig. 7.8). Because EIN/AH is the immediate precursor to endometrioid adenocarcinoma, both are commonly present in an endometrial sample. If uncertainty about the presence of carcinoma prevails, a diagnosis of “at least atypical hyperplasia/endometrioid intraepithelial neoplasia” is appropriate with a comment that the histopathologic features in the sample fall short of a definitive diagnosis of endometrioid adenocarcinoma. Therapeutic options for EIN/AH consist of hormonal therapy and surgery (hysterectomy). The decision about which treatment option is pursued rests with the clinician and is influenced by various patient-related factors such as age, desire for future fertility, and comorbidities.

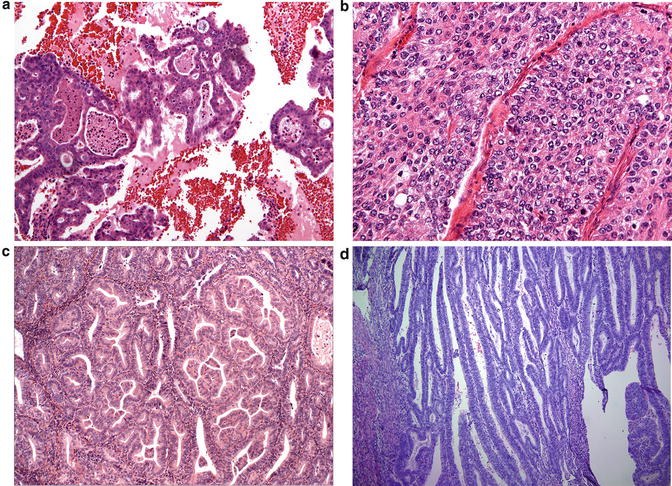

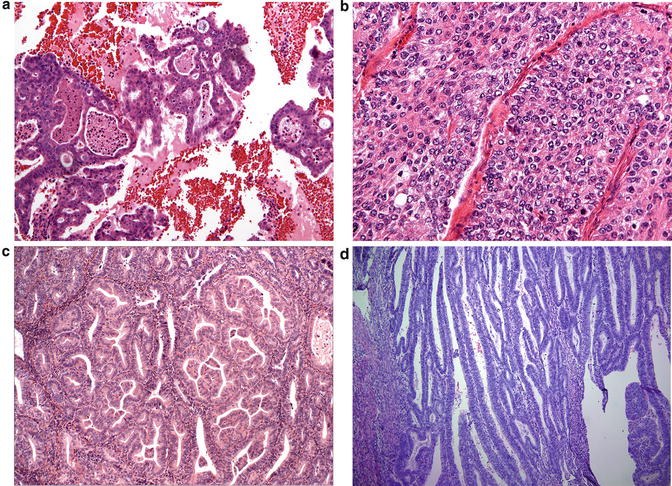

Fig. 7.8

Exclusion of endometrial adenocarcinoma is key in diagnosing EIN/AH. Histologic features indicative of carcinoma include (a) cribriforming, (b) non-morular solid growth, (c) papillary or mazelike glandular configurations, and (d) villoglandular architecture composed of thin papillary cores

Complicating Factors in the Diagnosis of EIN/AH

Sampling Artifacts and Specimen Fragmentation

Commonly observed in biopsy/curettage specimens, gland crowding due to artificial gland compression or telescoping of glands can occur; however, this is usually a focal finding, and the absence of cytologic demarcation is a helpful clue (Fig. 7.9). Fragmentation of samples represents a particular challenge to the pathologist. The EIN/AH criteria should be rigidly applied to prevent overdiagnosis and retain diagnostic specificity. The diagnosis of EIN/AH should only be rendered in intact fragments that meet all diagnostic criteria and contain intact intervening stroma. Even if extensively fragmented, the size criterion of 1 mm must be met in a single intact fragment; separate lesional foci should not be added to meet the size threshold. If a fragmented biopsy demonstrates features suspicious for EIN/AH (Fig. 7.10), obtain additional levels. If still no resolution is achieved, a descriptive diagnosis with a comment advising re-biopsy in 3 months is recommended.

Fig. 7.9

Telescoping artifact may mimic glandular crowding. Note the absence of cellular stroma adjacent to the artifactually compressed glands

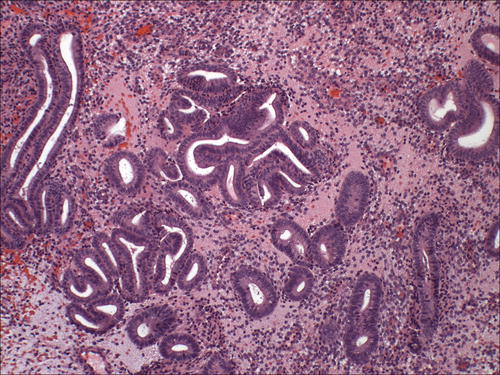

Fig. 7.10

This small fragment of tissue contains a cluster of crowded glands that is suspicious for EIN/AH

So-Called Over-Run EIN/AH

A discrete focus of gland crowding with appropriate cytologic demarcation and size leads to a straightforward diagnosis of EIN/AH. However, in one-fifth of endometrial samples, EIN/AH encompasses the entire specimen, so-called over-run EIN/AH (Fig. 7.11). On low-power examination, the differential diagnosis includes endometrial hyperplasia without atypia. Hence, a careful search for cytologic demarcation becomes critical. Native endometrial glands in over-run EIN/AH are often interspersed between lesional glands or are present at the periphery (Fig. 7.12). If no background endometrium is identified, the pathologist must decide whether the architectural complexity and cytologic atypia are in keeping with a diagnosis of EIN/AH and cannot be explained by a benign process. Immunohistochemistry (see below) such as staining with PAX2 may be of value in this setting.

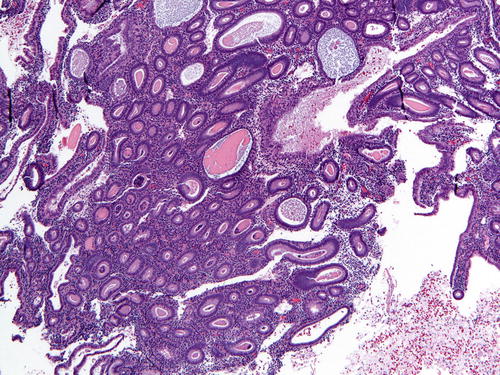

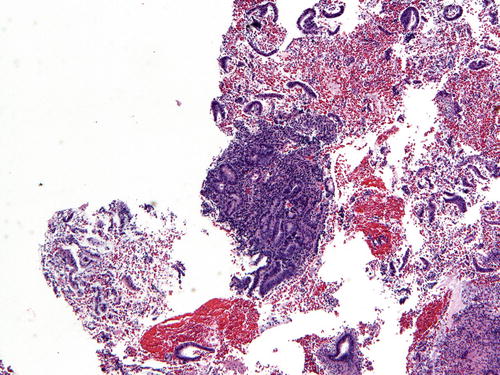

Fig. 7.11

Occasional samples will lack apparent normal background glands to evaluate for cytologic demarcation (so-called over-run EIN/AH )

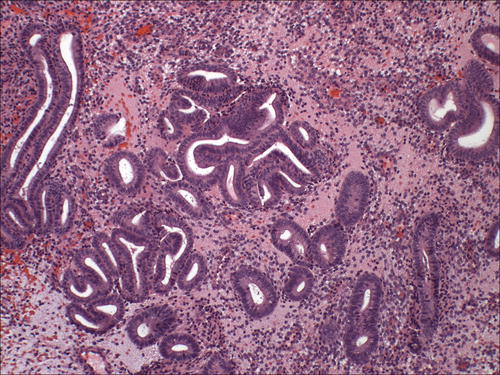

Fig. 7.12

In cases of over-run EIN/AH, a diligent search for normal background glands will often demonstrate rare normal glands (bottom center)

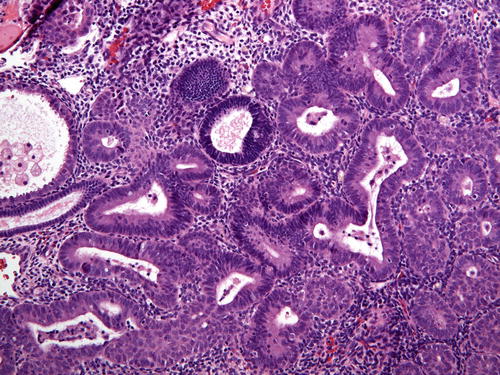

Polyps

Fragments of benign endometrial polyps can be confused with EIN/AH because glands may be crowded, haphazardly arranged, dilated and branched, and may display altered cytology. The fibrous stroma and thick-walled vessels are key features for the correct diagnosis (Fig. 7.13). One-fifth of EIN/AH arise in an endometrial polyp. Postmenopausal women are more likely to have polyps containing EIN/AH compared to premenopausal women [45]. Assessment for features of EIN/AH within a polyp can be challenging due to the inherently variable distribution and variable cytology of glands. All criteria for the diagnosis of EIN/AH must be met; of note, evaluation of cytologic demarcation is performed by comparing the cytology of the crowded glands to the background glands within the polyp rather than to the native endometrium outside of the polyp (Fig. 7.14) [45].