16 Pre-Eclampsia—Eclampsia Syndrome E. Albert Reece Pre-eclampsia and eclampsia are part of the same disorder, which occurs only during pregnancy and the postpartum period and afects both the mother and the unborn baby. Typically, it occurs after 20 weeks of gestation (in the late second or third trimester or middle to late pregnancy), though it can occur earlier. Proper prenatal care is essential to diagnose and manage pre-eclampsia, otherwise it can rapidly progress to severe pre-eclampsia and ultimately eclampsia, a serious, life-threatening condition. It is important to note, however, that research shows that more women die from pre-eclampsia than eclampsia, and one is not necessarily more serious than the other. Fortunately, it is a condition that, if detected early, can be properly managed with minimal negative consequences for mother and baby. Pre-eclampsia—sometimes referred to as pregnancy-induced hypertension—is defined by high blood pressure measured on two occasions at least 6 hour apart and excess protein in the urine after 20 weeks of pregnancy. (Note that both hypertension and proteinuria must be present for the diagnosis of preeclampsia to be valid). Often, pre-eclampsia causes only a modest increase in blood pressure. However, if pre-eclampsia is left untreated it can lead to more severe complications, including cerebral and vascular disturbances, edema, pain, liver dysfunction, and a low platelet count (Table 16.1). At this stage, it is known as severe pre-eclampsia. Eclampsia is the final and most severe phase of pre-eclampsia and occurs if severe pre-eclampsia is left untreated. It is characterized by convulsions and usually occurs after the onset of pre-eclampsia, although sometimes there are no recognizable symptoms. The convulsions characteristic of eclampsia may appear before, during, or after labor. However, eclamptic seizures are relatively rare and occur in less than 1% of women with pre-eclampsia.

Definition and Diagnosis

| Pre-eclampsia |

| Blood pressure: 140 mmHg or higher systolic or 90 mmHg or higher diastolic after 20 weeks of gestation in a woman with previously normal blood pressure |

| Proteinuria: 0 3 g or more of protein in a 24-hour urine collection (usually corresponds with 1+ or greater on a urine dipstick test) |

| Severe pre-eclampsia |

| Blood pressure: 160 mmHg or higher systolic or 110 mmHg or higher diastolic on two occasions at least 6 hours apart in a woman on bed rest |

| Proteinuria: 5 g or more of protein in a 24-hour urine collection or 3+ or greater on urine dipstick testing of two random urine samples collected at least 4 hours apart |

| Other features include: oliguria (less than 500 mL of urine in 24 hours), cerebral or visual disturbances, pulmonary edema or cyanosis, epigastric or right upper quadrant pain, impaired liver function, thrombocytopenia, intrauterine growth restriction |

| Eclampsia Cerebral accidents:

|

Hypertensive disorders:

|

Space-occupying central nervous system lesions:

|

Infectious diseases:

|

Metabolic diseases:

|

| HELLP Syndrome |

| Hemolysis |

| Abnormal peripheral blood smear (burr cells, schistocytes) |

| Elevated bilirubin ≥ 1.2 mg/dL |

| Increased LDH more than twice the normal upper limit |

| Elevated liver enzymes |

| Elevated ALT or AST ≥ twice the normal upper limit |

| Platelet count <100 000/µL |

The four recognized stages of eclampsia are as follows:

- Premonitory stage, which is usually missed unless constantly monitored; the woman rolls her eyes while her facial and hand muscles twitch slightly.

- Tonic stage, soon after the premonitory stage, in which the twitching turns into clenching. The patient may bite her tongue as she clenches her teeth, while her arms and legs become rigid. Her respiratory muscles also may spasm, causing her to stop breathing. This stage continues for around 30 seconds.

- Clonic stage, in which the spasm stops but her muscles start to jerk violently. Frothy, slightly bloodied saliva appears on her lips and can sometimes be inhaled. After a few minutes the convulsions stop, leading into the final stage: a coma. In some cases, there is heart failure as well.

- Comatose stage: the patient falls deeply unconscious and exhibits noisy, labored breathing, which can last only a few minutes or may persist for hours.

The HELLP (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets) syndrome is a variant of pre-eclampsia, although considerable controversy exists regarding its definition, diagnosis, incidence, etiology, and management. Thrombocytopenia with a platelet count of ≤100 000/μL is considered to be a hallmark of HELLP.

Pre-eclampsia Versus Chronic Hypertension

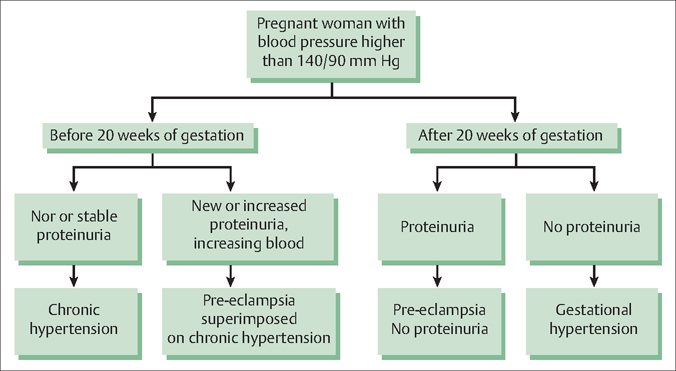

It is important to distinguish between pre-eclampsia and chronic hypertension. Chronic hypertension is defined by an elevated blood pressure that predates the pregnancy, is documented before 20 weeks of gestation, or is present 12 weeks after delivery. In contrast, pre-eclampsia— eclampsia is defined by elevated blood pressure and proteinuria occurring after 20 weeks of gestation (Fig. 16.1).

However, chronic hypertension may be complicated by superimposed pre-eclampsia (or eclampsia), which is diagnosed when there is an exacerbation of hypertension and the development of proteinuria that was absent earlier in the pregnancy. Approximately 15–30% of chronically hypertensive women develop superimposed pre-eclampsia. Conditions necessary for the diagnosis of superimposed pre-eclampsia include:

- the sudden exacerbation of blood pressure in a woman with previously well-controlled hypertension on antihypertensive medication

- the new onset of proteinurea (≥0.5 g of protein in 24-hour urine collection) in a woman with chronic hypertension but no proteinurea prior to 20 weeks gestation

- a worsening of proteinurea in a woman with chronic hypertension and proteinurea prior to 20 weeks’ gestation

- a new onset of aspartate aminotransferase (AST) or alanine aminotransferase (ALT) anomalies in the liver

- a new onset of thrombocytopenia with a platelet count of ≤100 000/μL

- a new onset of symptoms of severe pre-eclampsia (e.g., persistent headache, right upper quadrant pain, epigastric pain, scotomata, nausea, and vomiting)

Fig. 16.1 An algorithm for differentiating among hypertensive dis orders in pregnant women Reproduced with permission from Wagner LK Diagnosis and management of preeclampsia American Family Physician 2004; 70(12):2318 (Fig. 1)

Prevalence and Epidemiology

Pre-eclampsia is a complication of an estimated 7–10% of all pregnancies in the developed world. Eclampsia afects just under 1 in 50 women, with 1 in 14 fetuses of affected women dying despite best-available medical care.

Etiology and Pathophysiology

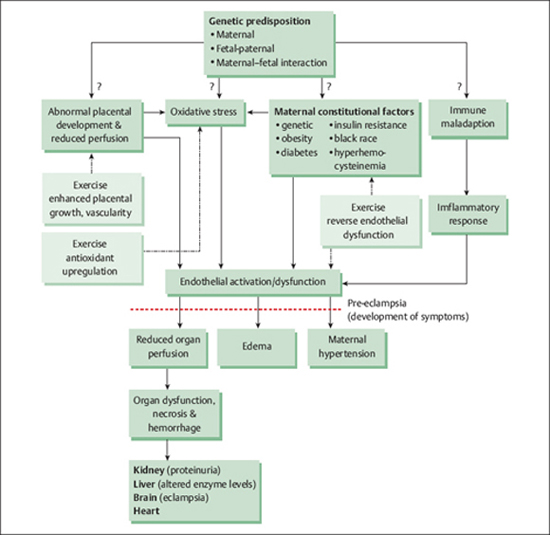

The exact causes of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia are still being investigated. Although some researchers suspect maternal constitutional factors, such as genetics, poor nutrition, or high body fat as potential contributors, other theories focus on problems of placental development and perfusion, oxidative stress, or immune factors (Fig. 16.2).

It is important to remember that although hypertension and proteinuria are the diagnostic criteria for preeclampsia, they are only symptoms of the underlying pathophysiologic changes that occur in the disorder.

Fig. 16.2 Potential mechanisms for the etiology of pre-eclampsia–eclampsia Adapted with permission from Weissgerber TL et al The role of regular physical activity in preeclampsia prevention Medical Science and Sports Exercise 2004; 36(12):2028 (Fig 1)

One of the most striking physiologic changes that occur in pre-eclampsia—eclampsia is intense systemic vasospasm, which is responsible for decreased blood flow to virtually all of the organ systems of the mother’s body. This reduced blood flow to major organs is further exacerbated by the activation of the blood’s coagulation cascade, which results in the development of microthrombi.

History

As part of their initial prenatal assessment, pregnant women should be asked about potential risk factors for pre-eclampsia, including their obstetric history and specifically whether they have experienced hypertension or pre-eclampsia during a previous pregnancy. The medical history also should include questions to identify any pre-existing medical conditions that increase the risk for pre-eclampsia, including diabetes mellitus, hypertension, vascular and connective tissue disease, nephropathy, and antiphospholipid antibody syndrome.

After 20 weeks of gestation, pregnant women should be asked during each prenatal visit about specific pre-eclampsia symptoms, including whether they may be experiencing any visual disturbances, persistent headaches, epigastric or right upper quadrant pain, and increased edema. Questions about these symptoms are included in many standardized prenatal documentation forms.

Physical Examination

The chief complaints of women presenting with pre-eclampsia may include acute headache, visual disturbances, and vomiting with upper abdominal pain. On examination, their refexes will be very brisk, even to the state of clonus. Their blood pressure will be high, and they will have elevated proteinuria. Some women, however, are asymptomatic at the time they are found to have pre-eclampsia, making it sometimes difficult to detect.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree