J. Patel

• Epidemiology of HIV in Pregnancy

• Pregnancy and Risks of Transmission

MANAGEMENT OF HIV IN PREGNANCY

• Use of Antiretroviral Agents in Pregnancy

BACKGROUND

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is a retrovirus that can cause life-threatening opportunistic infections, malignancies, and can eventually lead to acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) and death when untreated. HIV can be transmitted through bodily fluids, such as blood, semen, vaginal fluid, and breast milk. The transmission of HIV from mother to child in pregnancy has been of paramount concern for the past three decades with recent medical advancements leading to a low rate of perinatal transmission.

Epidemiology of HIV in Pregnancy

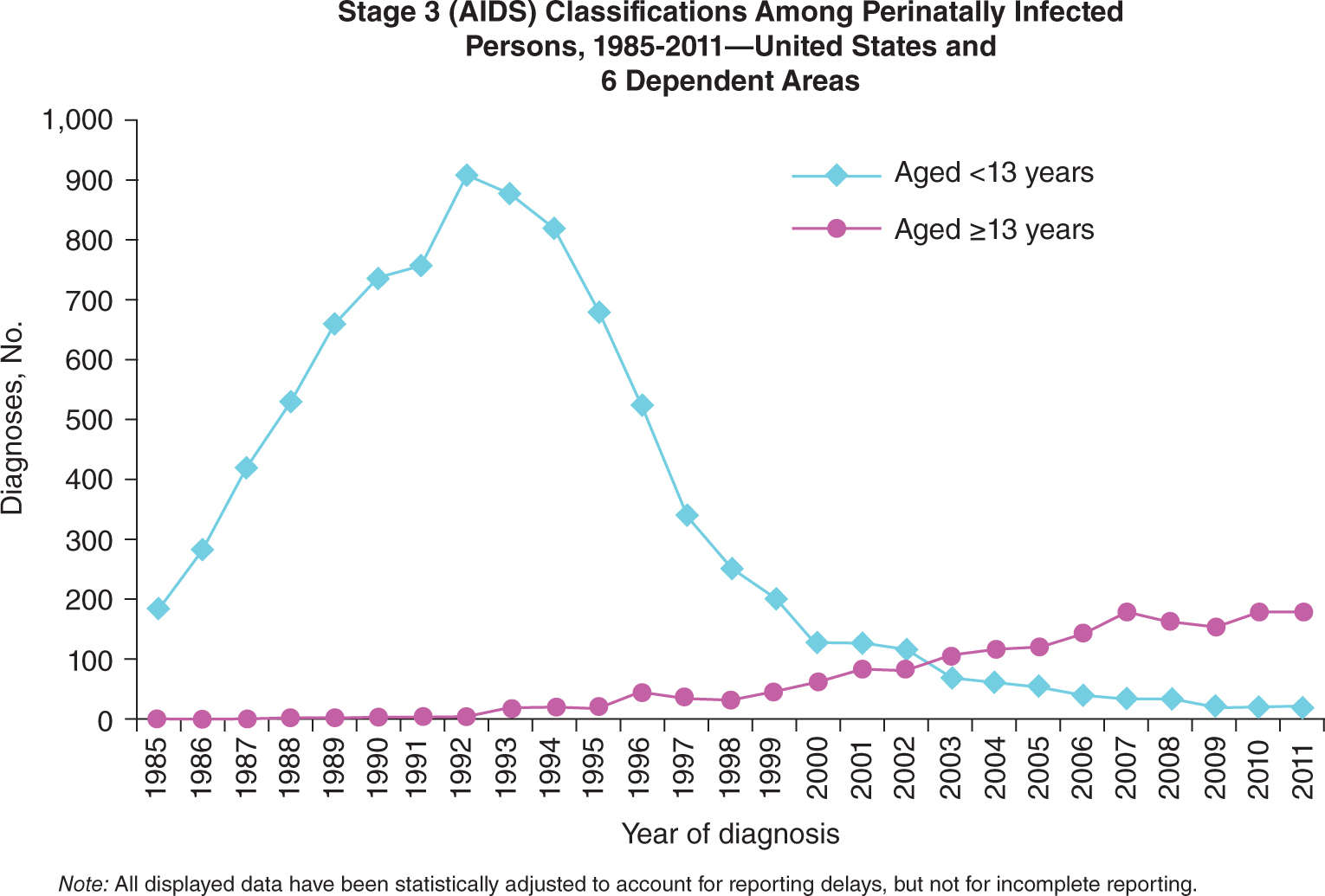

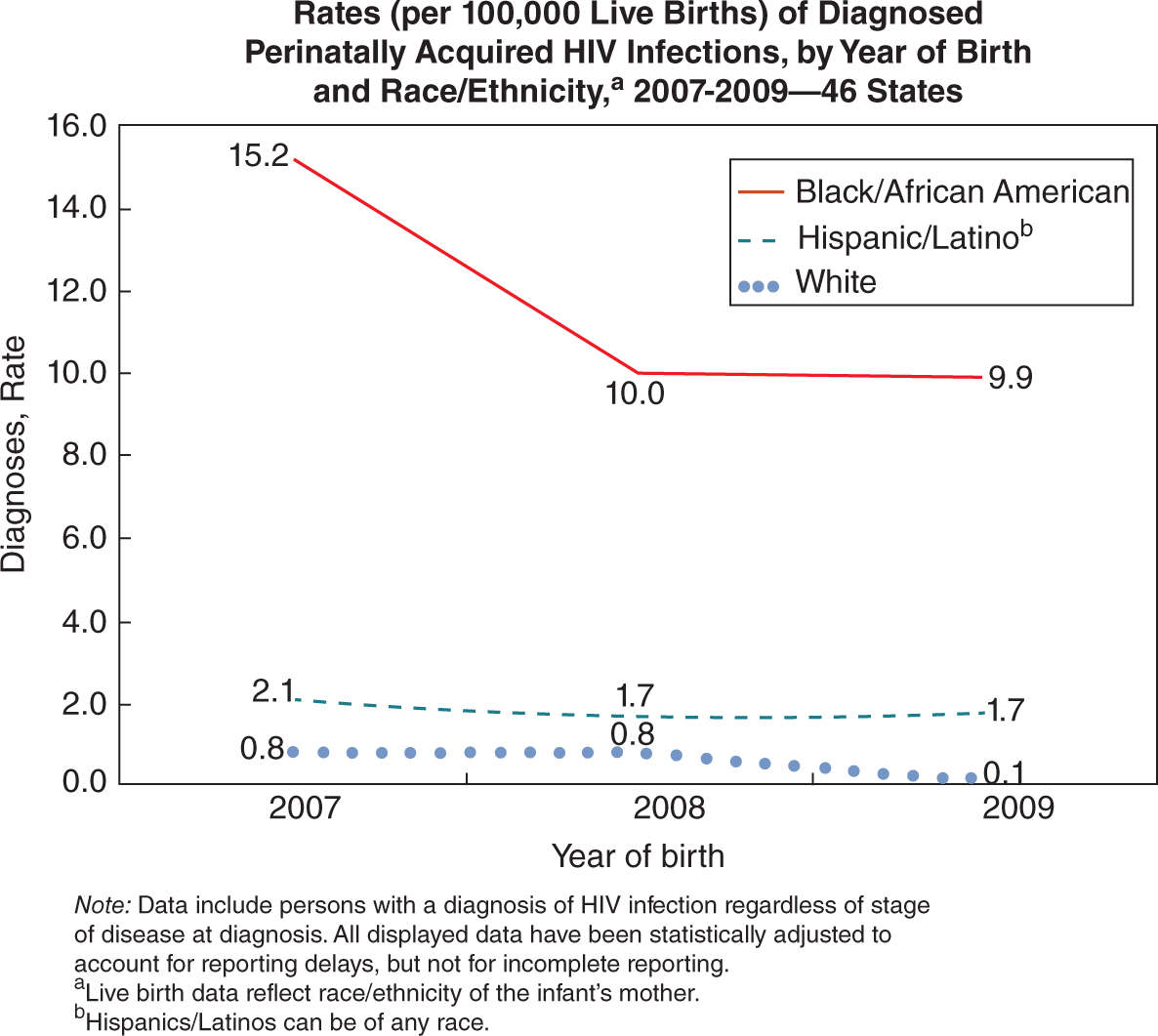

Perinatal infection is the most common route of HIV infection in children. The risk of this transmission has decreased from 25% without intervention to <2% with currently available medical treatments in developing countries.1 In the past two decades, routine HIV testing in pregnancy and appropriate intervention have led to more than a 90% decline in mother-to-child transmission (MTCT) in the United States (Figures 16-1 and 16-2). The Center for Disease Control (CDC) estimates that 1,144,500 persons older than 13 years of age are living with HIV infection, including 180,900 (15.8%) that are unaware of their infection. In 2010, an estimated 217 children younger than 13 years of age were diagnosed with HIV; 162 (75%) of those children were perinatally infected.2 The prevalence of HIV infection in prenatal clinics in the United States ranges from 0.13% to 5%.3–5 Because of early detection and intervention of HIV in pregnancy, less than 100 new cases of AIDS per year are diagnosed in the United States (Figure 16-1).

FIGURE 16-1. Number of cases of perinatal infection leading to AIDS in the United States, 1985-2011. Used with permission from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

FIGURE 16-2. Rates of perinatally acquired HIV infections by race from 2007 to 2009. From the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Pregnancy and Risks of Transmission

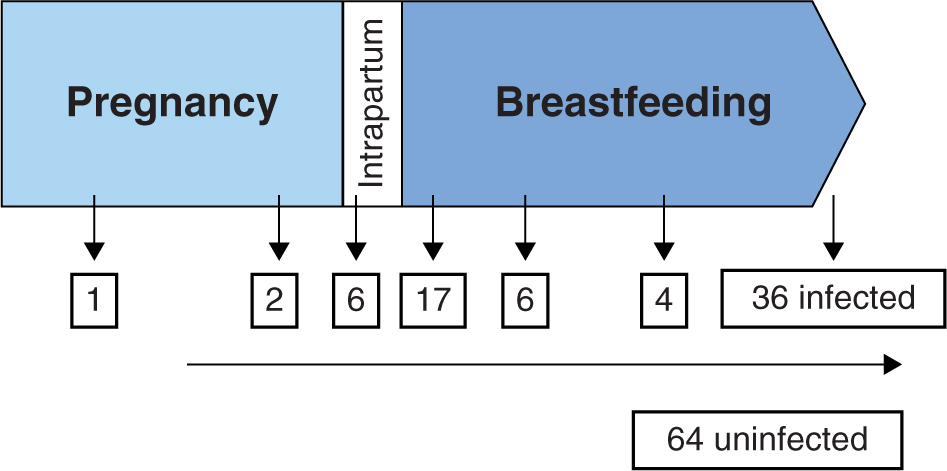

Although the rate of transmission has declined in recent years, there are several risks factors that impact MTCT. Without medical intervention, about two-thirds of MTCT occur during labor and delivery and one-third occurs in utero (Figure 16-3). In utero transmission mostly occurs during the third trimester of pregnancy. Breastfeeding also poses a significant risk of transmission of HIV. The most important predictor of perinatal transmission appears to be plasma HIV RNA load. Transmission can occur at any viral load but usually does not occur with viral loads <1000 copies/mL. Although the risk of transmission increases with increasing viral loads, there is no clear threshold above which all women transmit the virus.6 Other risk factors that contribute to MTCT include obstetrical complications such as prolonged and premature rupture of membranes, mode of delivery, and concomitant genital tract infections. Also neonatal low birth weight, cigarette smoke exposure, maternal substance abuse, and unprotected sex with multiple partners may pose a risk for increased transmission.7–10

FIGURE 16-3. Hypothetical cohort of 100 children with no intervention. The majority of MTCT occurs intrapartum. Without intervention, about 25% of children will be infected with HIV.

DIAGNOSING HIV IN PREGNANCY

All pregnant women in the United States should be screened for HIV infection. HIV testing during the first trimester of pregnancy is part of standard prenatal care and is legally required by all states. Written informed consent for HIV testing is not required in most states. Women have an option to opt-out of this screening; however, providers are recommended to discuss reasons for declining the test and encourage HIV screening at future prenatal visits. A second HIV test during the third trimester, preferably <36 weeks of gestation, is recommended by the CDC and should be considered for all pregnant women. Identifying a positive HIV screen before 36 weeks gestation allows for appropriate medical intervention to take place before vertical transmission has already occurred. This testing is especially important in women residing in areas with high HIV prevalence rates, those known to be at high risk for acquiring HIV, and women who have signs or symptoms consistent with acute HIV infection. The rationale for a second HIV test in the third trimester is to capture those women who may have become infected during pregnancy, either right before the initial screen and had not yet seroconverted or those infected after the first HIV test. Plasma RNA (viral load) should be measured along with an HIV enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) if acute retroviral syndrome is a possibility to diagnose acute HIV infection.11

Any pregnant woman with an unknown HIV status at the time of labor should have a rapid HIV test done unless she opts out of this screening. Immediate antiretroviral (ARV) prophylaxis should be started if the rapid HIV screen is positive without waiting for the confirmatory test.

Routine prenatal HIV screening is done with an ELISA assay that detects HIV antibodies. If ELISA is positive, it is followed by a confirmatory Western blot or an immunofluorescence assay. A positive ELISA followed by a confirmatory Western blot is 99% sensitive and specific. Typically, nine HIV antibodies can be identified on a Western blot, but minimal criteria for diagnosis include reactivity to two of the three following bands: gp120/160, p24, gp41. Most immunocompetent individuals will have detectable HIV antibodies via ELISA within 3 to 6 weeks of infection and a positive Western blot within 8 to 12 weeks.

If an ELISA is repeatedly positive and the Western blot contains some viral bands but not enough to make a definitive diagnosis, the sample will be labeled as “indeterminate.” An indeterminate test can represent either a false positive or very early HIV infection. This is resolved by a repeat Western blot 1 month later or by HIV RNA or DNA polymerase chain reaction.12

MANAGEMENT OF HIV IN PREGNANCY

Prenatal Care

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree