Chapter 25

Postpartum Tubal Sterilization

Joy L. Hawkins MD

Chapter Outline

Many parous women choose tubal ligation for permanent contraception. Half are performed postpartum (over 350,000 annually in the United States) and half as ambulatory interval procedures.1 Although the interval sterilization rate has declined by 12% in the United States, the postpartum sterilization rate remains stable, and postpartum sterilization is performed after 8% to 9% of all live births.1 The considerations and controversies regarding the administration of anesthesia for postpartum tubal sterilization are discussed in this chapter.

American Society of Anesthesiologists Guidelines

The American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) has published “Practice Guidelines for Obstetric Anesthesia,”2 which includes a discussion of postpartum tubal ligation. (See Appendix B.) The Task Force recommendations can be summarized as follows:

Surgical Considerations

Tubal sterilization can be performed satisfactorily at any time, but the early postpartum period has several advantages for women who have had an uncomplicated vaginal delivery.3 The patient avoids the cost and inconvenience of a second hospital visit. The uterine fundus remains near the umbilicus for several days postpartum, which allows easy access to the fallopian tubes. Minilaparotomy and laparoscopy have similar rates of serious complications (e.g., bowel laceration, vascular injury).4

There are at least two potential disadvantages to immediate postpartum sterilization. First, parous women are at increased risk for uterine atony and postpartum hemorrhage. This risk decreases substantially 12 hours after delivery. Second, immediate surgery results in sterilization before assessment of the newborn is complete. Postpartum tubal ligation is not wise if the patient is ambivalent regarding permanent sterilization. However, women who undergo postpartum sterilization have a similar probability of regret within 1 year of delivery (23.7%) as women who undergo interval sterilization (22.3%), although the risk is markedly increased when the woman is younger than 25 years of age.5

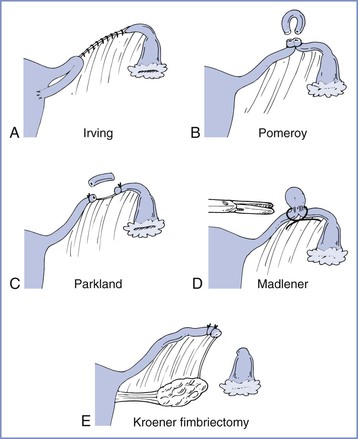

Several techniques are used for postpartum tubal sterilization (Figure 25-1).6 Puerperal sterilization has a failure rate that is lower than most interval procedures, and the failure rate is lowest (approximately 0.75%) if some form of tubal resection occurs.7 With the Irving procedure, the obstetrician buries the cut ends of the tubes in the myometrium and mesosalpinx. This technique is least likely to fail, but it requires more extensive exposure and increases the risk for hemorrhage. The Pomeroy procedure is simplest. The surgeon ligates a loop of oviduct and excises the loop above the suture. With the Parkland procedure, the obstetrician ligates the tube proximally and distally and then excises the midsegment. The last two methods are most commonly performed during postpartum tubal ligations. Regardless of the technique, the obstetrician should document that fimbriae are present to preclude ligation of another structure such as the round ligament. The excised portions typically are sent to a pathologist for verification.

FIGURE 25-1 Techniques for tubal sterilization. A, Irving procedure. The medial cut end of the oviduct is buried in the myometrium posteriorly, and the distal cut end is buried in the mesosalpinx. B, Pomeroy procedure. A loop of oviduct is ligated, and the knuckle of tube above the ligature is excised. C, Parkland procedure. A midsegment of tube is separated from the mesosalpinx at an avascular site, and the separated tubal segment is ligated proximally and distally and then excised. D, Madlener procedure. A knuckle of oviduct is crushed and then ligated without resection; this technique has an unacceptably high failure rate of approximately 7%. E, Kroener procedure. The tube is ligated across the ampulla, and the distal portion of the ampulla, including all of the fimbria, is resected; some studies have reported an unacceptably high failure rate with this technique. (From Cunningham FG, MacDonald PC, Gant NF, et al. Williams Obstetrics, 20th edition. Stamford, CT, Appleton & Lange, 1997:1376.)

A randomized clinical trial found a significantly increased risk for pregnancy at 24 months after use of the titanium clip for postpartum tubal occlusion (i.e., a cumulative pregnancy rate of 1.7 pregnancies per 1000 women who had titanium tubal occlusion versus 0.04 pregnancies per 1000 women in whom the Pomeroy technique was used).8 Therefore, evidence does not support routine use of the titanium clip for postpartum sterilization.8

Nonmedical Issues

Nonmedical issues affect decisions regarding the timing of tubal sterilization. The obstetrician must obtain and document informed consent for surgery.5 Tubal ligation should be considered an irreversible procedure. Therefore, most obstetricians require a discussion with the patient before labor and delivery. Postpartum partial salpingectomy has 5-year and 10-year failure rates of 6.3 and 7.5 per 1000 patients, respectively, the lowest of all sterilization procedures.5 Physicians should be aware of state laws or insurance regulations that may require a specific interval between obtaining consent and performance of sterilization procedures. Regulations often do not allow the woman to give consent while in labor or immediately after delivery. For example, the Medicaid reimbursement program includes the following requirements for sterilization8:

• The patient must be at least 21 years of age and mentally competent when consent is obtained.

• Informed consent may not be obtained while the patient is in labor or during childbirth.

In some cases the obstetrician may schedule a patient for a postpartum tubal ligation because of a fear that the patient will not return for interval tubal sterilization 6 weeks after delivery. Concerns regarding patient compliance should not prompt the performance of postpartum tubal ligation in patients with significant medical or obstetric complications. However, women who request postpartum tubal sterilization but do not receive it are more likely to become pregnant within 1 year of delivery (46.7%) than are women who did not request the procedure (22.3%).9

Preoperative Evaluation

The patient scheduled for postpartum tubal ligation requires a thorough preoperative evaluation, and a reevaluation should be performed even if the patient is known to the anesthesia provider as a result of the provision of labor analgesia. A cursory evaluation should not be performed simply because the patient is young and healthy. Patients with pregnancy-induced hypertension may safely receive neuraxial or general anesthesia for postpartum tubal ligation provided that there is no evidence of pulmonary edema, oliguria, or thrombocytopenia.10

Physicians and nurses often underestimate blood loss during delivery.11 Excessive blood loss from uterine atony is not uncommon in parous women. Orthostatic changes in blood pressure and heart rate should be excluded, especially if an immediate postpartum procedure is to be performed. At the University of Colorado, for surgery performed the day after delivery, the patient’s hematocrit is determined several hours after delivery (to allow for equilibration) and compared with the antepartum measurement. A hematocrit is not obtained before an immediate postpartum tubal sterilization (performed < 8 hours after delivery), provided that the antepartum hematocrit was acceptable, there are no orthostatic vital sign changes, and there was no evidence of excessive blood loss during delivery.

No absolute value of hematocrit requires a delay of surgery, but physical signs of hemodynamic instability or laboratory evidence of excessive blood loss should prompt postponement of the procedure until 6 to 8 weeks postpartum. Fever may signal the presence of endometritis or urinary tract infection and also may require postponement of surgery until a later date. Finally, the condition of the neonate should be confirmed before surgery to exclude any unexpected problems.

Mothers may be concerned that medications administered during surgery might affect their ability to breast-feed or that these medications might harm the newborn. Any drug present in the mother’s blood will be present in breast milk, with the concentration dependent on factors such as protein binding, lipid solubility, and degree of ionization.12 Typically, the amount of drug present in breast milk is small. Opioids, barbiturates, and propofol administered during anesthesia are excreted in insignificant amounts. (See Chapter 14 for a detailed discussion of interactions between drugs and breast-feeding.)

Risk for Aspiration

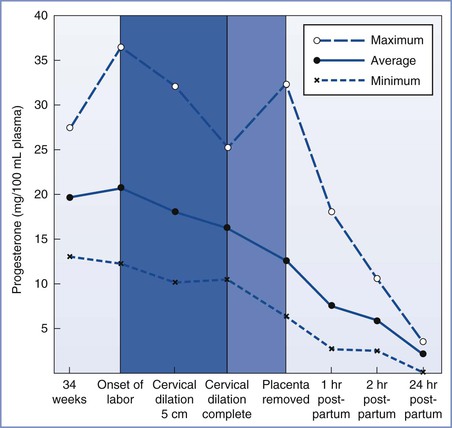

Historically, anesthesiologists have considered maternal aspiration the major risk associated with anesthesia for postpartum tubal ligation, although the evidence for this is scant and conflicting. A review of anesthesia-related maternal mortality found no maternal deaths associated with aspiration during postpartum tubal ligation, despite tracking deaths for 1 year after delivery.13 However, several factors may place the pregnant woman at increased risk for aspiration. Some but not all of these factors are resolved at delivery. The placenta is the primary site of progesterone production, and progesterone concentrations fall rapidly after delivery of the placenta (Figure 25-2).14,15 Typically, progesterone concentrations decline within 2 hours of delivery; and by 24 hours postpartum, progesterone concentrations are similar to those found during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle.

FIGURE 25-2 Average progesterone concentrations with the highest and lowest measurements of 13 pregnant women at given time intervals. (From Llauro JL, Runnebaum B, Zander J. Progesterone in human peripheral blood before, during and after labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1968; 101:871.)

Two important questions to address during the preanesthetic evaluation are (1) What is the duration of the fast for solids? (2) Were parenteral opioids administered during labor?

Gastric Emptying

Several studies have assessed gastric emptying in pregnant and postpartum women. In summary, the preponderance of evidence suggests that (1) administration of an opioid during labor increases the likelihood of delayed gastric emptying during the early postpartum period, (2) gastric emptying of solids is delayed during labor in all parturients, and (3) gastric emptying of clear liquids is probably not delayed unless parenteral opioids were administered. However, there are few data on gastric emptying during the first 8 hours postpartum.

O’Sullivan et al.16 used an epigastric impedance technique to compare gastric emptying times for solids and liquids in women during the third trimester of pregnancy, in women during the first hour postpartum, and in nonpregnant controls. The investigators observed that the overall rate of gastric emptying was lower in the postpartum patients than in pregnant or nonpregnant patients. When patients who had received parenteral opioids in labor were separated from those who had not, rates of gastric emptying for women who had not received opioids were similar to those for nonpregnant controls. The investigators concluded that the rate of gastric emptying in postpartum women is delayed only if opioids have been administered during labor.

Other studies have used the acetaminophen (paracetamol) absorption technique to assess gastric emptying. Gin et al.17 studied women on the first and third days after delivery and at 6 weeks postpartum. They found comparable times to peak concentration of acetaminophen in all three groups. They concluded that gastric emptying was no different in the immediate postpartum period than 6 weeks later, and they recommended that “the approach to prophylaxis against acid aspiration should be more consistent between nonpregnant and postpartum patients.” Whitehead et al.18 observed no significant delay in gastric emptying during the first, second, or third trimesters of pregnancy or between 18 and 48 hours postpartum when compared with gastric emptying in nonpregnant controls. They observed that gastric emptying was significantly delayed during the first 2 hours after vaginal delivery, but at least 4 of the 17 women studied received intramuscular meperidine during labor. The researchers did not measure gastric emptying between 2 and 18 hours postpartum. Despite the confounding use of opioids, they concluded, “The presence of delayed gastric emptying in the immediate (within 2 hours) postpartum period confirms that strict precautions against acid aspiration should be provided to mothers who are newly delivered and requiring anaesthesia.”19

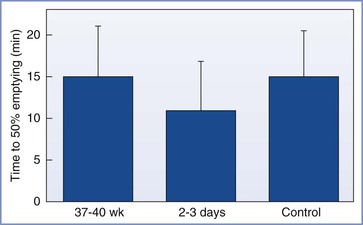

Sandhar et al.19 used applied potential tomography to measure gastric emptying in 10 patients at term gestation, 2 to 3 days postpartum, and 6 weeks postpartum. The 6-week measurement served as each woman’s control value. All measurements were made after administration of an H2-receptor antagonist. The times to 50% emptying after ingestion of 400 mL of water were not different among the three periods of testing (Figure 25-3).

FIGURE 25-3 Mean (SEM) times to 50% gastric emptying (min). No significant differences were noted between term pregnant, postpartum, and nonpregnant control women. (From Sandhar BK, Elliott RH, Windram I, Rowbotham DJ. Peripartum changes in gastric emptying. Anaesthesia 1992; 47:197.)

Wong et al.20 assessed gastric emptying in nonlaboring pregnant women at term gestation, after ingestion of either 50 or 300 mL of water, by using two techniques: (1) serial assessment of acetaminophen absorption and (2) use of ultrasonography to determine gastric antrum cross-sectional areas. Gastric emptying was significantly faster after ingestion of 300 mL of water, consistent with the observation that a liquid meal may actually accelerate gastric emptying. Repeating the study in obese women showed similar results.21 Kubli et al.22 compared the effects of isotonic “sport drinks” versus water on residual gastric volume in women in early labor. Women who received isotonic “sports drinks” had similar gastric volumes and a similar incidence of vomiting as compared with those who received water, but the ingestion of “sport drinks” prevented the increase in ketone production that occurred in the control (water) group. Altogether, these studies suggest that gastric emptying of clear liquids is not delayed during pregnancy, early labor, or the postpartum period unless an opioid has been administered.

In contrast, Jayaram et al.23 found that 39% of postpartum patients, but not nonpregnant patients presenting for gynecologic surgery, had solid food particles in the stomach, as demonstrated by ultrasonography. Four hours after a standardized meal, 95% of postpartum women—compared with only 19% of nonpregnant subjects—still had solid food particles in the stomach. Prior administration of an opioid did not seem to be a risk factor in this study. Scrutton et al.24 randomized 94 women presenting in early labor to receive either a light diet or water only during labor. The mothers who ate a light diet had significantly larger gastric antrum cross-sectional areas (determined by ultrasonography) and were twice as likely to vomit at or around delivery as those who had water only. Also, the volumes vomited were significantly larger in the women who ate a light diet.

During the preoperative assessment of any woman scheduled for postpartum tubal ligation, the anesthesia provider should determine when the patient last consumed solids and whether opioids were administered by any route. Systemic absorption of an opioid occurs after epidural administration. However, published studies have provided conflicting results regarding the effect of epidural opioid administration on gastric emptying. Wright et al.25 observed that epidural administration of 10 mL of 0.375% bupivacaine with fentanyl 100 µg caused a modest prolongation of gastric emptying during labor when compared with epidural administration of bupivacaine alone. However, Kelly et al.26 found that intrathecal, but not epidural, fentanyl delayed gastric emptying. Metoclopramide may not accelerate gastric emptying in patients who have received an opioid.

Gastric Volume and pH

There is little evidence that postpartum women are at greater risk for sequelae of aspiration than patients undergoing elective surgery based solely on pregnancy-induced changes in gastric pH and volume. The conventional wisdom is that a gastric volume of more than 25 mL and a gastric pH of less than 2.5 are risk factors for aspiration pneumonitis. Coté27 noted that this dogma was derived from unpublished animal studies and that it assumes that every milliliter of gastric fluid is directed into the trachea. A marked disparity exists between the incidence of patients labeled “at risk” and the incidence of patients with clinically significant aspiration pneumonitis.

Blouw et al.28 measured gastric volume and pH in nonpregnant women undergoing gynecologic surgery and postpartum women 9 to 42 hours after delivery. They found no significant difference between the groups. Approximately 75% of women in both groups had a gastric pH of less than 2.5. When the combination of volume and pH was used to determine the risk for aspiration, 64% of the control patients but only 33% of postpartum patients were at risk. The researchers concluded that 8 hours after delivery, postpartum patients are not at greater risk than nonpregnant patients undergoing elective surgery. They did not examine patients earlier than 8 hours after delivery. In addition, they acknowledged that a large number of patients in both groups are at risk.

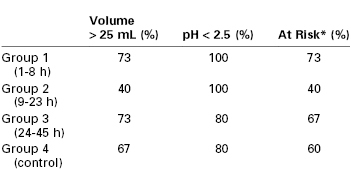

James et al.29 attempted to determine the “safe” interval after delivery. They compared gastric pH and gastric volume in postpartum women 1 to 8 hours, 9 to 23 hours, and 24 to 45 hours after delivery with a control group of nonpregnant women undergoing elective surgery. There were no significant differences in either parameter between the group of patients undergoing elective surgery and any of the postpartum groups (Table 25-1). Approximately 60% of all patients were considered “at risk” for aspiration pneumonitis. The investigators concluded that there was no difference in the risk for sequelae if aspiration should occur, but they speculated that hormonal changes or mechanical factors might make aspiration more likely during the postpartum period.

Finally, Lam et al.30 administered 150 mL of water to 50 women 2 to 3 hours before tubal ligation that was performed 1 to 5 days postpartum. Another 50 postpartum and 50 nonpregnant women fasted after midnight. The authors found no differences in gastric pH or volume among the postpartum-water group, the postpartum-fasted group, and the group of nonpregnant controls undergoing elective surgery.

Gastroesophageal Reflux

Women in the third trimester of pregnancy have decreased lower esophageal barrier pressures as compared with nonpregnant controls.31 Those with symptoms of heartburn have even lower pressures and a higher incidence of gastric reflux. Vanner and Goodman32 asked parturients to swallow a pH electrode to measure lower esophageal pH at term and on the second postpartum day. Patients were placed in four positions: supine with tilt, left lateral, right lateral, and lithotomy, and were then asked to perform a Valsalva and other maneuvers to promote reflux. A total of 17 of 25 patients had reflux at term, whereas only 5 of 25 had reflux after delivery. The investigators concluded that the incidence of reflux returns toward normal by the second day after delivery. However, this conclusion is arguable given the fact that they did not determine normal by defining the incidence of reflux before or 6 to 8 weeks after pregnancy.

Summary

No data indicate that the postpartum patient’s safety is enhanced by delaying surgery or is compromised by proceeding with surgery immediately after delivery. This situation has led to confusion and inconsistency in the development of policies for the performance of postpartum tubal ligation.33 No waiting interval guarantees that the postpartum patient is free of risk for aspiration. It is probably prudent to use some form of aspiration prophylaxis in all patients undergoing postpartum tubal ligation. However, significant aspiration pneumonitis is so rare that it will be difficult to document cost-effectiveness and decreased rates of morbidity and mortality from the use of these measures. H2-receptor antagonists and antacids do not reduce the possibility of regurgitation and aspiration, but they may make the consequences less severe. Metoclopramide (a prokinetic agent) may decrease the incidence of reflux by increasing lower esophageal sphincter tone and hastening gastric emptying.32

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree