Treatment Recommendations

Modalities for Postoperative Pain and Effusion

Controlling postoperative pain and effusion is crucial secondary to their role in muscle inhibition.30–32 Treatment options for swelling include cryotherapy and joint compression through the use of compression wrap. Cryotherapy, electrical stimulation, and passive range of motion (PROM) may reduce pain.19,32 In contrast, ultrasound should not be used on the skeletally immature athlete’s joint secondary to contraindications on growth plates.32

The speed of weight-bearing progression and joint loading may affect pain and swelling. In general, we recommend our patients stay out of school for 3 to 5 days to minimize pain and effusion as well as use bilateral upper extremity crutches for at least 4 weeks to control loading of the knee joint.

Bracing and Ambulation

Advanced fixation techniques allow for immediate weight bearing. Postoperatively, partial weight bearing is instructed with a hinged brace locked in extension to emphasize full knee extension and assist while the quadriceps is inhibited.17,33,34 Studies have demonstrated improved functional knee scores and proprioception with brace use after surgery.33,34

The athletes are advancing to weight bearing as tolerated (WBAT) with an assistive device over the next 2 weeks. Mechanical loading of the knee is progressed with the use of an assistive device over the first 4 to 6 weeks to allow the knee joint to acclimate to increased loads with minimal pain and effusion.

Brace education is reviewed on the initial visit with both the patient and caregiver secondary to its importance for graft protection and maintenance of knee extension ROM. The clinician should encourage frequent brace checks throughout the day as the brace may loosen and slide distally, facilitating a flexed knee gait, which may cause loss of knee extension.

Range of Motion

ROM may begin immediately secondary to graft placement in the native footprint of the ACL27 and is strongly encouraged to minimize the effects of immobilization such as excessive collagen formation.35–37 Full passive knee extension is emphasized while flexion is gradually restored. Extension is critical for normalized gait.38 Flexion contractures cause excessive loading on the patellofemoral joint, leading to pain and quadriceps weakness.38,39

Specific exercises targeted toward achieving knee extension are supine hamstring stretches, gastrocnemius stretches with a towel, and towel roll extension. For towel roll extensions, a towel roll is placed under the patient’s heel/ankle while lying supine with a low-load, long-duration stretch.

Flexion ROM is gradually progressed and depends on the individual’s response to surgery as well as apprehension and age. Constant reassurance should be provided to the child that no damage will occur with ROM exercises. If persistent effusion exists, ROM may advance at a slower pace. ROM should progress gradually in phase 1 rather than aggressively at the expense of increased pain, effusion, and apprehension delaying recovery.

Patient and caregiver are instructed on performing seated active-assisted knee flexion/passive extension exercises three to five times per day. When approximately 80 degrees of flexion ROM is achieved, a short crank bike (140 to 180 mm) may be used to develop endurance, strength, and ROM (Fig. 12.1). The shorter crank allows patients to cycle full circles prior to achieving appropriate ROM necessary to start on a standard bike (170 mm).

Patella Mobilizations

Patella mobilizations are performed to minimize decreased ROM and quadriceps inhibition.39 Loss of mobility may result secondary to excessive scar tissue adhesions along the medial and lateral, fat pad retinacula, and harvesting the patellar tendon for the graft.39,40 If patellar mobility is lost, infrapatellar contractures may result in ROM complications and difficulty with quadriceps activation.39–41 Mobilizations are performed in both the medial/lateral and superior/inferior directions, especially for those with a patellar tendon autograft. Superior mobility of the patella is required for complete knee extension and inferior glides for flexion.39–41

Strengthening

Reestablishing voluntary quadriceps control is crucial. Quadriceps setting with a towel roll under the knee is used for reeducation and, when combined with neuromuscular electrical stimulation, has been found to be more efficient than exercise alone to improve strength.42 Once patients demonstrate good quad contraction, they are progressed to straight-leg raises with the brace locked until sufficient quadriceps control is demonstrated. When no quadriceps lag is demonstrated, they may perform straight-leg raises without the brace. When achieved with appropriate endurance, the brace may be unlocked for ambulation.

We recommend incorporating closed kinetic chain (CKC) leg press when ROM is greater than 90 degrees of flexion and quadriceps control improves. Leg press is performed bilaterally inside a pain-free arc (70 to 75 degrees) and advanced to a unilateral exercise using greater ROM in later phases. Closed kinetic exercises are used for strengthening in the early phases, as they have been shown to minimize stress to the ACL.19,20

Proximal hip strength is crucial for stability as well as reducing loads at the knee.2,8,11 Progressive resistance exercise can be performed with cuff weights and isotonic exercises. In later phases, core and proximal hip strength will be crucial for ensuring minimal valgus loading with dynamic activities.

Neuromuscular Training

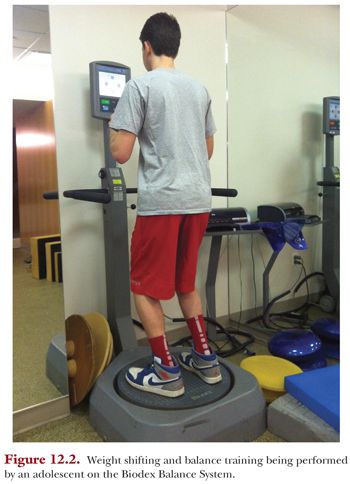

Neuromuscular training is emphasized because balance deficits have been identified following ACL reconstruction as well as extensive reports in the literature regarding neuromuscular deficits being a risk factor for injury.3,8,43,44 A rocker board can be used as soon as the patient is 50% weight bearing. Training starts with basic weight shifting in both the medial/lateral direction. A Biodex Balance System (Biodex Medical Systems, Shirley, NY) tends to be fun for young patients and may be used to demonstrate weight shifting and weight bearing (Fig. 12.2). In addition, wall squats may be performed for joint repositioning and weight bearing as well. In later phases, squats may be progressed to unstable surfaces such as a tilt board once the patient exhibits good postural control and lower extremity alignment on solid surfaces.

POSTOPERATIVE PHASE 2 (WEEKS 4 TO 8): INTERMEDIATE PROTECTION PHASE

In phase 2, the graft is not optimal. The literature has reported that the graft undergoes a period of necrosis, revascularization, and remodeling. Graft strength decreases during this period of necrosis and gradually increases as it remodels.12,14,16,45 Constant reinforcement with activity modification is required to ensure the individual does not push past his or her physiologic capabilities injuring the graft.

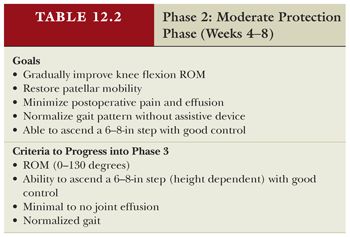

The goals are continued emphasis on protection of the surgical repair, controlled effusion, flexion ROM, good patellar mobility, normalized gait, and the ability to ascend a 6- to 8-in step (height dependent) pain-free with good control (Table 12.2).

Treatment Recommendations

Modalities

Cryotherapy continues to be emphasized secondary to gradually increased loads to the joint with activity as well as to minimize quadriceps inhibition. Electrical stimulation for quadriceps reeducation should be discharged at this time secondary to improved quadriceps contraction.

Bracing and Ambulation

As quadriceps strength improves and the patient demonstrates the ability to perform a straight-leg raise without a quadriceps lag, he or she may change to a postoperative brace as per the surgeon’s preference. The brace serves as a reminder to the individual and his or her friends to avoid activities that may risk reinjury. Mechanical loading of the knee is progressed during this phase, and the athlete is advanced off of crutches by 6 to 8 weeks, pending normalized gait and extension ROM. We have found that if progressed off of crutches too quickly and without sufficient quad control, patients are at risk of losing knee extension secondary to ambulating on a flexed knee.

Range of Motion

Flexion is gradually progressed to full flexion by 8 to10 weeks postoperatively. This can be achieved by progressing the athlete from seated active-assisted range of motion (AAROM) knee flexion to wall slides (Fig. 12.3A) and a stair stretch (Fig. 12.3B). The clinician should monitor these exercises to ensure compliance with repetitions and sets as well as quality of performance. As ROM progresses from 110 to 115 degrees, cycling is advanced to a standard 170-mm ergometer. Low-peak strain values have been demonstrated on the ACL with stationary cycling.45,46

Strengthening

As ROM and strength continues to improve, additional CKC exercises are added such as squats, leg press, advanced neuromuscular activities, and unilateral CKC exercises. Weight on the leg press is progressed and determined by the athlete’s physiologic capabilities as well as quality of movement. Despite popular belief that weight training affects growth plates in children, studies have demonstrated no adverse effects.47 In contrast, strength training has demonstrated a reduction in the number and severity of knee injuries in adolescent athletes.48–52 It is recommended that a clinician supervise children at all times while on equipment to ensure safety as well as appropriate weight, repetitions, and quality of movement.47 Children should be educated to perform movements slowly and controlled with equal weight acceptance to translate over to functional activities.

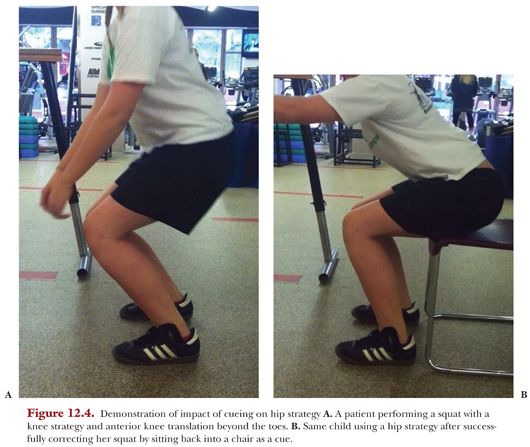

Squats are progressed from wall slides to free squats. Wall squats and barbell squats have been shown to be effective and safe regarding tensile loads on the ACL. Weight-bearing squats have been reported to have an ACL tensile load of 50 N versus non–weight-bearing knee extensions demonstrating 150 N.20,53,54 Quality of movement is key to avoid adverse loading of the ACL as well as develop compensatory movement patterns. Anterior knee translation beyond the toes may increase ACL loading during squatting exercises.20,54 Studies have demonstrated improved lower extremity alignment with verbal feedback and direct supervision in young athletes.2,55,56 The use of a chair gives the child a cue to sit back and use a hip strategy to prevent anterior knee translation (Fig. 12.4). A mirror may be used for visual feedback if the individual presents with an asymmetrical weight shift. For children who present with weak gluteal musculature and resultant valgus, TheraBands may be used above the knee to activate hip abductors. In addition, it should be understood that the child has potentially never learned proper squatting technique and the clinician may be the first to teach him or her.

Unilateral CKC exercises are added such as contralateral hip abduction and extension with a TheraBand to activate gluteus medius early on as well as address single-leg weight bearing. Forward step-ups are gradually progressed with various step heights for strengthening based on proper alignment and technique. Retrograde treadmill ambulation is used with progressive inclines to facilitate quadriceps strengthening pending patient age and coordination.57 Proximal hip strengthening exercises are continued and advanced as ROM allows, such as clamshells, bilateral lower extremity bridging, and lateral band walking.

Neuromuscular Training

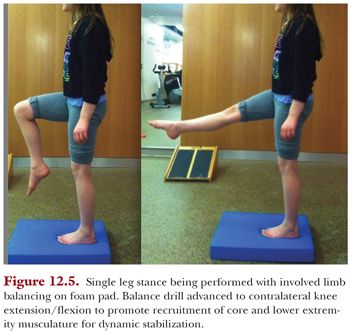

As proprioception improves, dynamic stabilization drills are progressed to include unilateral weight bearing and multi-planar activities using a rocker board or foam pad. Single-limb activities on flat ground are progressed to unstable surfaces with the knee slightly flexed to encourage agonist/antagonist cocontraction to enhance knee stability. Single-limb stance with uninvolved lower extremity movements is performed as well in the latter part of this phase (Fig. 12.5). These balance drills with extremity movements promote dynamic stabilization and recruit various muscle groups.19 Improving neuromuscular reaction time to imposed loads will enhance dynamic stabilization around the knee and assist with protecting the graft from reinjury.19,58 Perturbation training has been proven effective in rehabilitation programs58–60 and can be performed while the patient is performing double- or single-limb balance exercises on an unstable surface.

Flexibility

Quadriceps stretching in the supine and prone position is used to assist with flexion ROM by week 6. Hamstring and calf flexibility should not be neglected secondary to the impact they have on functional mobility. Quadriceps and hamstring flexibility is critical to allow for sufficient knee and hip flexion during sports to reduce ACL strain.3,61

PHASE 3: FUNCTIONAL STRENGTHENING AND CORRECTIVE MOVEMENT (8 TO 16 WEEKS)

This phase is dedicated to building a sound strength base to serve as the foundation for advanced movement skills in the next phase. Neuromuscular control, proximal hip strength, core stability, and eccentric quadriceps strength are advanced. Continued focus on proper alignment and control with all movements continues to be emphasized, as athletes will not advance to dynamic sports-specific movement skills unless demonstrated. Running and jumping is not performed until an adequate strength base is achieved to avoid adverse loads to the graft (Table 12.3).

Treatment Recommendations

Addressing Range of Motion and Flexibility Deficits

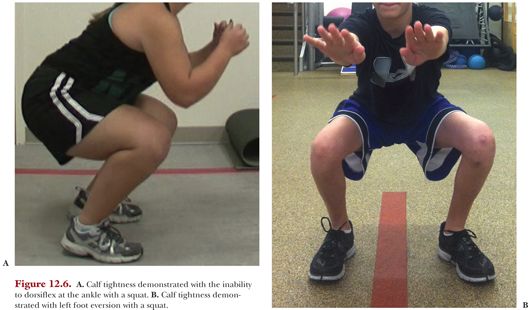

The clinician will typically need to address deficits incurred by growth spurts. Quadriceps, hamstring, and gastrocsoleus flexibility is critical to allow for sufficient knee and hip flexion during maneuvers such as cutting to reduce ACL strain.2,36,61 Flexibility deficits can result in compensatory movement patterns as well as cause valgus loading of the knee. The inability to dorsiflex at the ankle without the heels lifting up off the ground during a squat (Fig. 12.6A) as well as movements such as foot eversion are indicative of calf tightness (Fig. 12.6B).

Strengthening

Leg press is progressed from bilateral to unilateral as well as eccentric work. For eccentric quadriceps strengthening, the individual is to extend with bilateral lower extremities and slowly lower with one leg. A forward step-down program is introduced with progressive heights (4 to 6 to 8 in). Quality of movement is continually assessed for risk factors that may predispose the athlete to injury as well as guide the clinician to areas that need to be addressed.

Addressing Neuromuscular Imbalances: Reducing Risk Factors

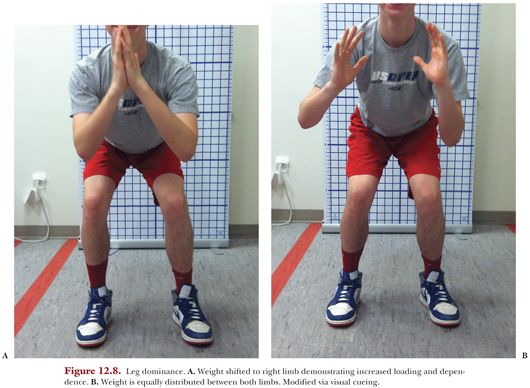

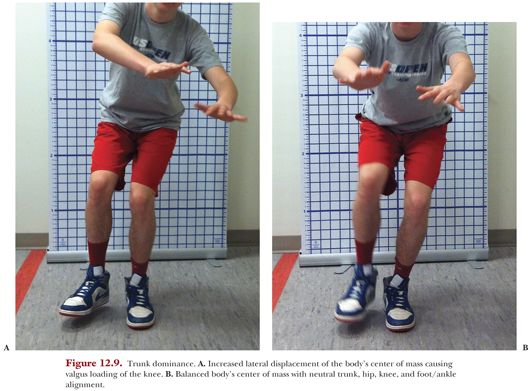

Basic foundational movement patterns are to be perfected prior to advanced agility and plyometrics to avoid adversely loading the ACL. Young athletes demonstrate several measurable neuromuscular imbalances associated with increased injury risk such as quadriceps dominance, leg dominance, and trunk dominance.3,48,62–64 Children who demonstrate ligament dominance tend to stress the ligament before muscular activation to absorb ground reaction forces (GRFs). This may occur secondary to lack of dynamic muscular control, leading to increased valgus moment and potential for high torque at the knee and ACL (Fig. 12.7A,B). Quadriceps dominance results from preferential activation of the knee extensors versus the knee flexors during movements leading to hyperextension of the knee and predisposition to ACL injury. Leg dominance is a result of imbalances in muscular strength and coordination, which may place either leg at risk. The weaker limb is compromised secondary to the inability to dissipate forces and the stronger limb is subjected to higher forces secondary to increased dependence and loading (Fig. 12.8A,B). Trunk dominance pertains to excessive trunk motion in the frontal plane, leading to high GRFs and knee joint abduction loads leaving the knee vulnerable to injury. Trunk dominance may be caused by increased motion of the body’s center of mass during single-leg landing, pivoting, or deceleration as well as weak core strength (Fig. 12.9A,B).3,48,62–64

Strengthening for Correction of Dynamic Valgus

Strengthening specific areas have been shown to minimize at-risk movement patterns.47–49,64 Gluteus maximus and medius play a role in preventing dynamic valgus collapse by controlling hip adduction and femoral rotation. Weakness results in inability to maintain the hip in an abducted position during squatting as well as single-leg activities such as landing and cutting. Studies have demonstrated improved control of dynamic valgus collapse with gluteus maximus and medius strengthening.65,66 Side planks and lateral band walking have been shown to produce sufficient maximal voluntary activation for strengthening of the gluteus medius. Single-limb activities are performed to activate the gluteus medius to maintain a level pelvis.67 Single-limb squats and deadlifts (Fig. 12.10) have been shown to maximally elicit gluteus maximus. These exercises are progressed from double-limb to single-limb stance when appropriate strength and technique is demonstrated.2,67 Hamstring weakness and activation deficits have been shown to control dynamic valgus postures by resisting anterior and lateral tibial translation and rotations.68 Deficits in hamstring strength result in quadriceps dominance secondary to increased knee extensor moments over knee flexor moments, therefore increasing risk of injury.69–71 Wilk et al.60 demonstrated improved hamstring and quadriceps activation when a knee-flexed position to 30 degrees was held during an exercise such as balancing.