CHAPTER 66 Polycystic Ovary Syndrome

Western medical perspective

Description

In particular, the triad of amenorrhoea, hirsutism and obesity in the presence of polycystic ovaries was considered to be the essential feature of this disease.1

Nowadays it is widely recognized that PCOS is more than the classic Stein–Leventhal syndrome, as women with polycystic ovaries exhibit a wide spectrum of clinical presentations. Moreover, it is now apparent that the above triad of manifestations (amenorrhoea, hirsutism and obesity) together with bilateral polycystic ovaries is associated with a number of other endocrine disorders of diverse aetiology.2 These may include Cushing’s syndrome, congenital adrenal hyperplasia, ovarian hyperthecosis, hypothyroidism and chronic anovulation in association with hyperprolactinaemia.3

PCOS often comes to light during puberty due to menstrual problems, which affect around 75% of those with the disease. Infrequent, irregular or absent periods are all common variations, many finding their periods particularly heavy when they do arrive. Indeed, a study of 100 women with PCOS found that case histories suggest endocrine aberrations occurring before puberty, prior to the final establishment of the hypothalamic–pituitary–ovarian system.5

The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists lists the following facts about PCOS:

Endocrinology

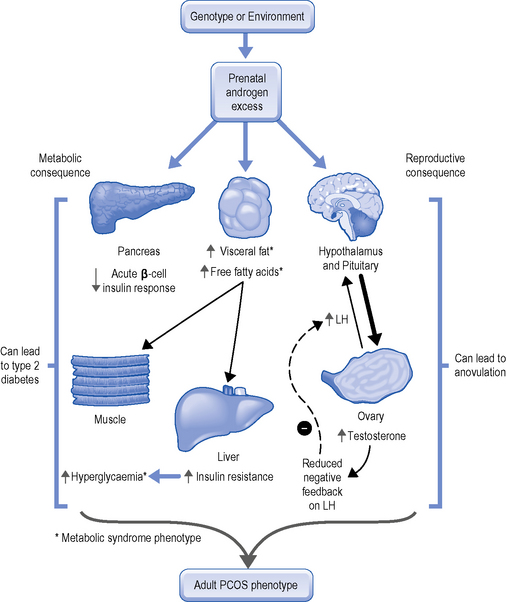

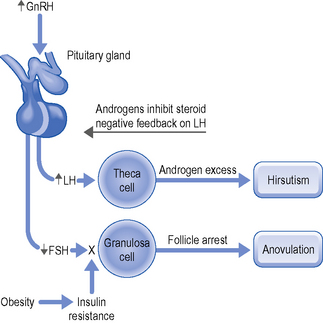

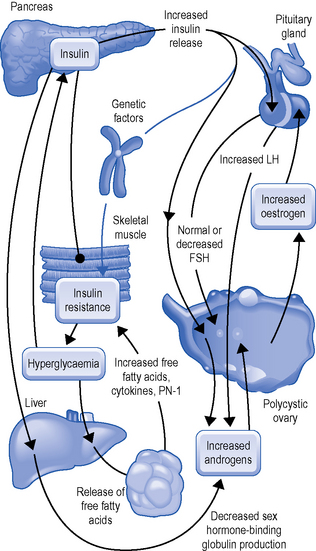

Endocrinologically, PCOS is also heterogeneous; classically it is characterized by hyperandrogenism, inappropriate pituitary gonadotropin secretion (which causes an elevated luteinizing hormone (LH) to follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) ratio) and hyperinsulinism (see Fig. 66.1).

The degree of hirsutism associated with PCOS does not always correlate closely with the magnitude of androgen excess. Severe hirsutism may be associated with a slight elevation of androgens, while a substantial elevation of androgens may not always result in hirsutism.7

A major feature of PCOS is chronic anovulation with elevated levels of LH with low levels of FSH (Fig. 66.2). This abnormality in the LH and FSH is the result of a disruption in the feedback mechanism of the hypothalamic–pituitary–ovarian axis. The cyclical changes in ovarian oestrogen normally responsible for appropriate feedback regulation of cyclical gonadotropin release are overruled by a constant outpouring of oestrogen from extra-glandular sources. Thus, the secretion of excessive amounts of androgens and their subsequent conversion to oestrogen constitute the basis for the development of chronic anovulation in PCOS (Fig. 66.3).8

Yen summarizes the endocrinology of PCOS as follows:

The pathophysiology of chronic anovulation is not related to an inherent defect of the hypothalamic–pituitary–ovarian axis. Inappropriate gonadotrophin secretion with a high LH/FSH ratio is causally related to an elevated and relatively constant oestrogen feedback on the hypothalamic–pituitary–ovarian system. The LH-dependent hyperplasia of the theca cells and the associated hypersecretion of ovarian androgens are responsible for the high oestrogen levels through conversion of androgen to oestrogen by extra-ovarian tissues and inhibit sex-hormone binding globulin (SHBG) production. The low SHBG levels facilitate the rapid tissue uptake of free androgens for peripheral formation of oestrogen, and the increased adipose tissue provides excessive sites for androgen to oestrogen conversion. The high levels of oestrogen, in turn, augment pituitary sensitivity to luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH) with the secretion favouring LH over FSH and results in self-perpetuating acyclicity with chronic anovulation.9

Patients with a history of anovulatory infertility and/or oligomenorrhoea or amenorrhoea and no evidence of recent corpora lutea were designated ‘anovulatory PCO’, and those ovaries from women reporting regular cycles which met the above morphological criteria, but in which a dominant follicle and/or a recent corpus luteum was observed, were designated ‘ovulatory PCO’. Normal morphology was assigned when the ovary was of normal size with soft, pliable stroma and contained not more than five follicles greater than 2 mm in diameter in a woman with regular menstrual cycles.10

Diagnosis

Ultrasound scan

This is usually done as an internal scan, i.e. a small ultrasound probe is placed just inside the vagina, giving the best view of the ovaries and pelvic organs. In PCOS, the ovaries are found to have multiple, small cysts around the edge of the ovary. These cysts are only a few millimetres in size, do not in themselves cause problems and are partially developed eggs that were not released (Plate 66.1). The cysts are usually lined with a few layers of granulosa cells and there is marked hyperplasia of the theca interna surrounding the many cystic follicles. It has been assumed that the hyperplastic theca cells are the result of chronic LH stimulation and the associated excessive androgen production.11

Clinical manifestations

The main clinical manifestations of PCOS are as follows:

Treatment

Infertility treatment

Ovarian stimulation

It should be noted that assisted-reproduction technology based on the use of ovarian stimulation is associated with an increased risk of multiple pregnancies, pregnancy complications, low birth weight, major birth defects and long-term disability among surviving infants.12

Chinese medical perspective

In Chinese medicine, PCOS may correspond to several different gynecological diseases (Fig. 66.5):

Clinical manifestations

Hirsutism

Hirsutism is due to a dysfunction of the Penetrating Vessel with imbalance between Qi and Blood. A deficiency of Blood in the Uterus leads to amenorrhoea, but this would mean that there is more Blood available in the Penetrating Vessel at the skin level in the chin to promote the growth of hair. According to Chapter 65 of the Spiritual Axis, the Penetrating Vessel brings Qi and Blood to the chin area and, in women, losing some blood with menstruation, the Penetrating Vessel has relatively less Blood than Qi in this area compared to men. The lack of Blood in this area is the reason why women do not have a beard; as men have relatively more Blood in the head branch of the Penetrating Vessel, this Blood promotes the growth of hair on the face.13

Obesity

Obesity always indicates Damp-Phlegm. In the case of PCOS, it affects both the Penetrating Vessel and the Directing Vessel (Ren Mai). Zhu Dan Xi (1281–1358) mentions obesity as a sign of Phlegm and a factor in infertility in women in his book The Heart of Dan Xi’s Treatment Methods (Dan Xi Zhi Fa Xin Yao): “Inability to conceive in obese women is caused by the fat blocking the Uterus and leading to amenorrhoea: one must use herbs that resolve Phlegm”.14 This passage clearly equates obesity with Phlegm.

Patterns

The main patterns appearing in PCOS are as follows:

Thus, the main patterns in PCOS are:

Comparison between PCOS and endometriosis

Treatment of the extraordinary vessels and of phlegm

Governing and Directing Vessel in combination

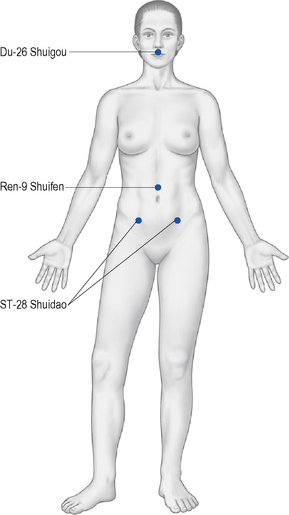

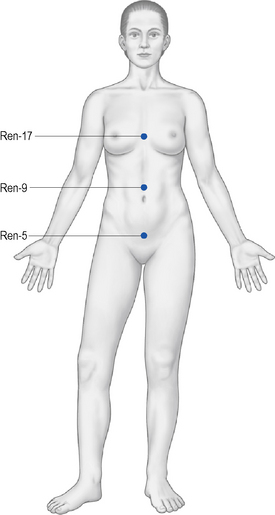

The main points that regulate the fluid metabolism in each Burner are as follows:

Two sets of three points for each Burner stand out: