CHAPTER 65 Endometriosis

Western medical perspective

Aetiology

Immunologic factors

The following are the risk factors in endometriosis:

As we discussed in Chapter 4 on aetiology, some doctors have advanced the hypothesis that the increasing incidence of endometriosis may be correlated with the increased number of menstrual cycles between the time of menarche and that of the first pregnancy.

Aetiology

Pathology

There are three diagnostic histologic features of endometriosis. They are:

The typical lesion will show an abundance of inflammatory cells and fibrous connective tissue.

Ovarian endometriosis occurs in the form of small superficial deposits on the surface of the ovary or as larger cysts which may be up to 10 cm in size (known as endometriomas or ‘chocolate cysts’) and which may rupture (Plate 65.1). In the ovary, the process is almost always bilateral. There is usually considerable fibrosis and puckering of the ovarian surface in the region of the cyst as well as adherence to neighbouring structures.

In the other most frequently involved areas, i.e. throughout the pelvic peritoneum, the lesions are normally smaller and more numerous and are surrounded by dense, fibrous scar tissue (Plate 65.2). Endometriosis is frequently accompanied by mesothelial hyperplasia of the pelvic peritoneum. Mesothelial hyperplasia most commonly involves the surface of the ovaries, the Fallopian tubes, the pelvic peritoneum and the omentum.1

Diagnosis

A diagnostic laparoscopy is the ‘gold standard’ for diagnosing endometriosis. A diagnosis of endometriosis should not be considered unless the endometriosis has been seen during a laparoscopy. Most gynecologists also insist that a biopsy of the endometrial tissue be examined by a pathologist before confirming the diagnosis (Plate 65.3).

Treatment

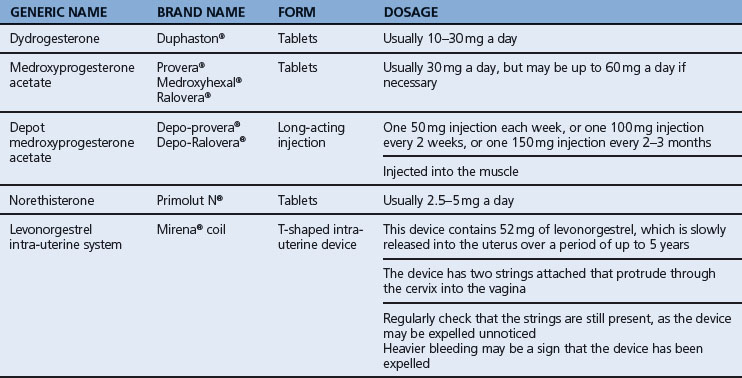

Combined contraceptive pill

Mirena® IUD

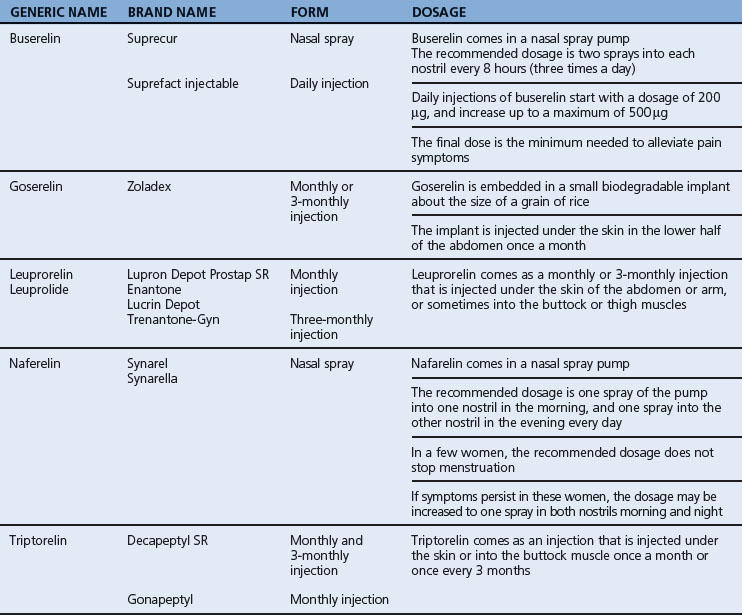

GnRH agonists

Table 65.2 lists the various types of GnRH agonists for endometriosis.

Aromatase inhibitors

Side effects of aromatase inhibitors

The most common side effects of aromatase inhibitors are mild hot flushes and decreased libido.

Chinese medical perspective

Aetiology

Intercourse during menstruation

When a woman becomes sexually aroused, the Minister Fire goes upwards. If this happens when menstrual blood is flowing downwards, the two will ‘meet’, blocking each other and therefore leading to stagnation of Qi and Blood in the Uterus (Fig. 65.1).

Tampons

Tampons block the normal downward flow of menstrual blood thereby leading to stasis of Blood.

Pathology

Blood stasis

We can assume that in endometriosis there is always Blood stasis. The very appearance of the endometriosis lesions confirms this: they always look purple, sometimes reddish-purple and sometimes bluish-purple (see Plate 65.2). The Blood stasis accounts for the menstrual pain experienced with endometriosis.

Temperature chart

The temperature chart is flat in endometriosis for two reasons, one due to the Manifestation (Biao), the other to the Root (Ben). The temperature does not decrease enough during the period because of Blood stasis (Biao) and it does not increase enough after ovulation due to Kidney-Yang deficiency (Ben). The result is a temperature chart line that is somewhat flat (Fig. 65.2).

To summarize, the main Full patterns (Manifestation) in endometriosis are: Blood stasis, Cold in the Uterus, Dampness and Damp-Phlegm. The main Empty patterns (Root) are: Kidney deficiency (Yin or Yang) and Blood deficiency (Table 65.3).

Table 65.3 Summary of the main patterns in endometriosis

| Manifestation | Root |

|---|---|

| Blood stasis | Kidney deficiency |

| Cold | Blood deficiency |

| Dampness | |

| Damp-Phlegm |

Pathology

Treatment principles

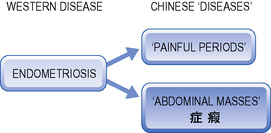

Before discussing treatment principles, we should discuss the relationship between the biomedical entity of ‘endometriosis’ and Chinese medicine gynecological diseases. As discussed in previous chapters, Painful Periods, Heavy Periods or Bleeding between Periods are ‘diseases’ (bing) in Chinese medicine (hence the use of initial caps) but not in Western medicine. In Western medicine, painful periods, heavy periods and bleeding in between periods are symptoms, not diseases (Fig. 65.3).

He Xian Lin and Frosolone say:

Although there are many ways to achieve the same goal, one thing is agreed upon by all sources with regard to endometriosis. The major pathology is that of Qi and Blood stagnation. Both patterns need to be addressed but at the root of it all there is Kidney-Qi deficiency. Attention should also be paid to treatment according to the four phases and predominance of the most severe symptom (dysmenorrhoea or menorrhagia/metrorrhagia).3