Pharmacology of Sleep

Introduction

This chapter will cover general principles of medication use for sleep disorders in children with a focus on sedative/hypnotic medications for insomnia in children and adolescents.1,2 Specific pharmacologic interventions for other sleep disorders (such as narcolepsy or restless legs syndrome) are discussed in those respective chapters. General recommendations will be described first, followed by a discussion of specific features of those sleep medications that have been identified as commonly used in pediatric settings.

It should be noted that – other than for the treatment of enuresis – the only medication currently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use in treating any sleep disorders in children under 18 years old is chloral hydrate (due to an old indication for its use in treating insomnia in children). In general, empirical data are limited regarding the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of pharmacologic interventions for sleep problems in the pediatric population. Most of the information available regarding use of these medications is taken from adult data or from case reports or small case series in pediatric populations. Only a few published studies have specifically examined the effectiveness of hypnotic/sedative use in children and adolescents in randomized placebo-controlled clinical trials. Despite this lack of evidence, a number of studies, in both the United States and Europe, suggest that prescribing, or recommending over-the-counter (OTC) use of, sedatives or hypnotics for sleep complaints is a relatively common practice among pediatricians, general practitioners, and child psychiatrists.3 Thus, while empirical data will be included whenever possible, recommendation for the rational use of these medications in clinical practice in this chapter will be largely based on recently developed consensus statements1,2 rather than on empirically based guidelines.

General Recommendations

Clinical Considerations

Combination of Treatment Modalities

Medication should rarely be the first choice or sole treatment. In almost all cases, medication should be used in combination with non-pharmacologic behavioral management strategies. Although pharmacologic interventions are likely to have a more rapid and potent effect, non-pharmacologic treatments have been shown to result in more sustained improvement (persisting after medication has been discontinued).4 Combining therapies also helps to minimize side effects.

Pharmacologic Considerations

Timing

Consideration should be given to the timing of drug administration relative to the targeted time of sleep onset (e.g., ‘within 30 minutes of lights out’). There should be awareness of the wakeful period that precedes sleep readiness. This is the circadian-mediated period of alertness that occurs in adults and children, (usually) in the evening hours, just before sleep onset during a 1- or 2-hour window in which it becomes difficult or almost impossible to fall asleep. This is the so-called second-wind or wake maintenance zone (see Chapter 4). Most hypnotic medications have their onset of action within 30 minutes of administration and peak within 1–2 hours. Thus, giving the medication too early (e.g., 2 hours before sleep onset) is not only less likely to be effective than dosing closer to bedtime but – when administered during this window of increased circadian alertness – may induce dissociative phenomenon (i.e., disinhibition and hallucinations).5

Drug–drug Interaction

Medication should be used with caution when there is a potential for pharmacodynamic drug–drug interaction with concurrent medications (e.g., opiates) or pharmacokinetic drug–drug interaction (e.g., between fluoxetine, a CYP2D6 and -2C19 inhibitor, and diphenhydramine).6

Metabolic Considerations

Based on the meager pediatric pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic data that exist for hypnotic drugs, it appears that some medications (such as zolpidem (Ambien®)) are metabolized differently in younger children (see below). These data suggest that children may require higher doses than adults.7 Additionally, a dose that is not adequate to induce sleep could result in a paradoxical reaction in which the child becomes groggy, and subsequently agitated and disinhibited.7

Tolerability

Adverse Effects

All medications prescribed for sleep problems should be closely monitored for the emergence of adverse effects. Some medications may even precipitate new, or exacerbate co-existing, sleep-related problems such as sleepwalking and daytime sleepiness. Discontinuation of these agents may also result in increased sleep problems. For example, when REM-suppressing medications are abruptly withdrawn, an increase in nightmares may be seen as a result of a subsequent rebound in REM sleep.8

Specific Medications Commonly Used for Pediatric Insomnia

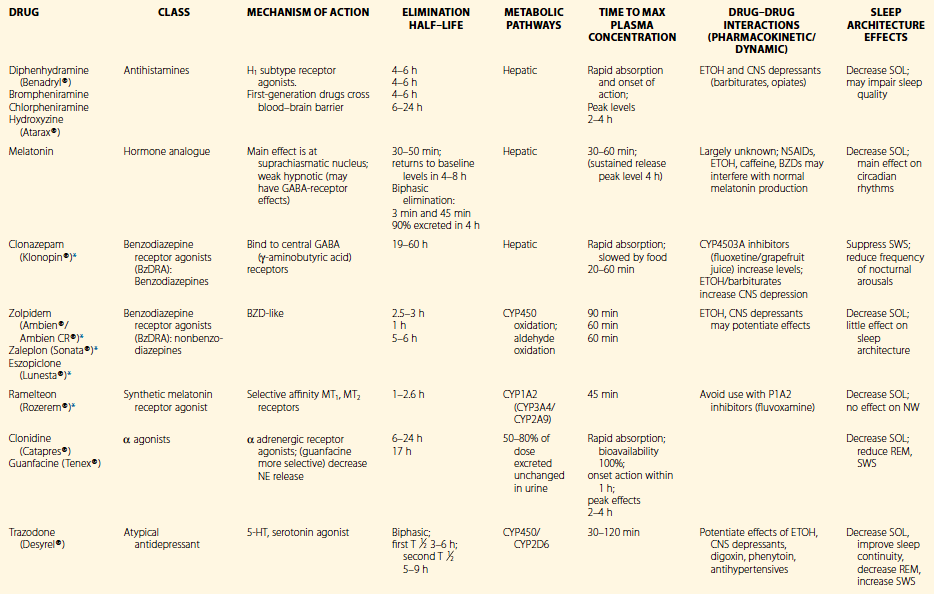

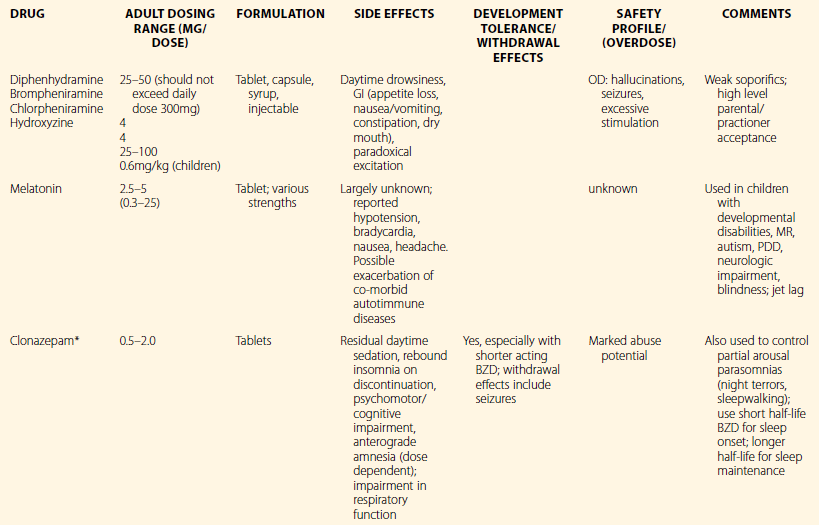

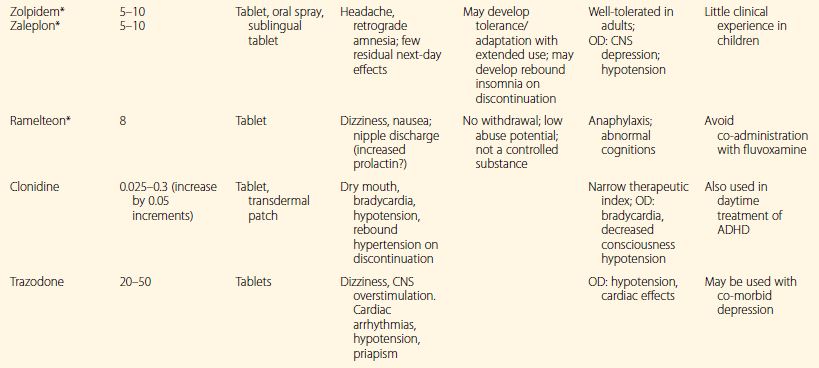

Summaries of pharmacologic and clinical properties of sedatives/hypnotics frequently used in pediatric clinical settings are presented in Tables 7.1 and 7.2. The following discussion describes drug properties and specific cautions regarding use in the pediatric population. OTC drugs are discussed first; then there follows a description of prescription medications that are currently FDA-approved for treatment of insomnia in adults (BZD receptor agonists, melatonin receptor agonists, low-dose doxepin).9 Prescription medications commonly used off-label for childhood insomnia are discussed below, but the order of presentation should not be interpreted as implying any preference (given that the currently available empirical evidence regarding safety and efficacy of pharmacological insomnia treatment in children is inadequate to rank recommendations). Of the OTC medications discussed, most do not have pediatric dosing listed by the manufacturer, and dosing in clinical practice is often determined by choosing a proportion of the adult dose.

Table 7.1

Pharmacology of Selected Medications Used For Pediatric Insomnia

*FDA-approved as hypnotic in adults.

Reprinted by permission of Oxford University Press, USA. From Owens, J. Insomnia in Children and Adolescents. Pediatric Psychopharmacology, 2003;2:660.

Table 7.2

Clinical Properties of Selected Medications Used for Pediatric Insomnia

*FDA-approved as hypnotic in adults.

Reprinted by permission of Oxford University Press, USA. From Owens, J. Insomnia in Children and Adolescents. Pediatric Psychopharmacology, 2003;2:660.

Nonprescription Medications

Antihistamines

Antihistamines – both OTC (e.g., diphenhydramine) and prescription (e.g., hydroxyzine) – are the most commonly prescribed or recommended sedatives in pediatric practice.3 Because of their widespread use and familiarity, many families and providers view antihistamines an acceptable choice for the treatment of childhood insomnia. Clinical experience suggests that these medications are generally well tolerated in children. First-generation drugs (diphenhydramine, hydroxyzine, chlorpheniramine) cross the blood–brain barrier and bind to H1 receptors in the central nervous system (CNS).10 By contrast, second- and third-generation antihistamines, such as terfenadine and loratadine, are significantly less sedating.10 Antihistamines are generally rapidly absorbed, and effects on sleep architecture appear to be minimal.10 Most OTC sleep aids (such as Tylenol PM®) contain diphenhydramine or doxylamine. A double-blind placebo-controlled study in 50 children with diphenhydramine HCL (1 mg/kg) showed significant subjective improvement in sleep latency and night waking.11 However, a more recent study in 6- to 15-month-old children found that diphenhydramine was no better than placebo in reducing night wakings.12

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree