INTRODUCTION

Dr. Alexander Brunschwig was the first to report on the complete excision of pelvic viscera for advanced cancer (i.e., pelvic exenteration) in 1948. He described this procedure as “the most radical surgical attack so far described for pelvic cancer and also [what] would appear to be the most radical of abdominal operations that have been carried out with some measure of consistency.” The first operation was performed on December 12, 1946, at Memorial Hospital, which eventually became Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, in New York.

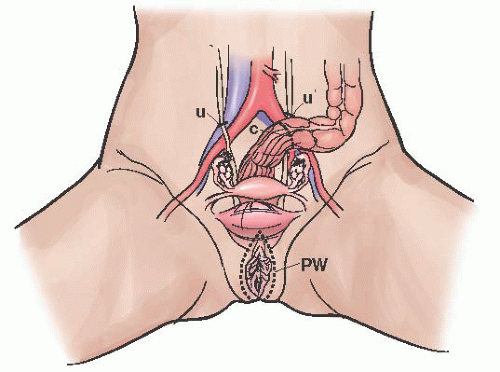

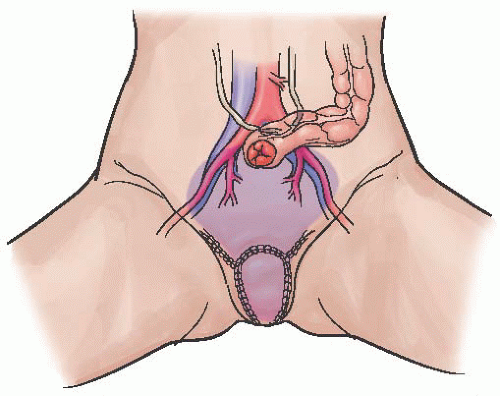

Figures 54.1 and

54.2 are diagrams from Brunschwig’s manuscript. This manuscript included 22 cases, 15 of which were recurrent cervical cancers, and follow-up was very short (maximum follow-up was 8 months). There were 5 (23%) perioperative mortalities and a total of 9 (41%) deaths within 8 months. Subsequent reports from the same institution of the same procedure in patients with ovarian and endometrial cancers described 5-year overall survival (OS) of 7% and 14%, respectively, with morbidities of over 60% and perioperative mortalities of 23%. In 1989, Lawhead and colleagues reported an updated series on mostly cervical cancer patients; the 5-year OS was 23%. These early reports suggested that the procedure had a perioperative mortality that was similar to the 5-year OS, at the cost of severe short-term and long-term morbidity as well as absence of vagina. Therefore, it fell out of favor and was infrequently performed for many years.

As surgical techniques and perioperative management improved over subsequent years, investigators began to report improving outcomes with decreasing perioperative mortalities. Additionally, publications after the year 2000 report continued decreases in perioperative mortality. These reports are described in greater detail later in the chapter. Pelvic exenteration is now felt to be a reasonable option in select cases, if performed by experienced surgeons. It can provide a chance at long-term cancer control and survival, but it remains a highly morbid procedure.

Pelvic exenterations can be modified based on the tumor size and location. There are multiple options for vaginal reconstruction as well as for different types of urinary system diversions separate from the fecal system. Permanent end colostomies are still required in the vast majority of cases, but in highly select situations, it may be possible to reconnect the large bowel and avoid a permanent colostomy. The indications for these pelvic exenterative procedures have also been expanded at certain institutions. More attention is also paid to sexual issues in these women as well as to overall quality of life after such extensive procedures. The most commonly performed exenteration is a total pelvic exenteration, followed by anterior, and then posterior (

Table 54.1).

INDICATIONS AND PREOPERATIVE EVALUATIONS

The selection of patients suitable for a pelvic exenteration is highly complex and individualized. The most common indication is recurrent cervical carcinoma limited to the central pelvis in a patient who has received prior full-dose pelvic radiotherapy (

Table 54.2). Exenteration is also considered in select cases of patients with recurrent endometrial, vulvar, or vaginal carcinomas. Uterine sarcomas are extremely rare. The majority of patients with these tumors will have extrapelvic sites of disease at the time of recurrence, in which case

exenterative procedures are contraindicated. However, in cases of pelvic-only recurrences in patients with uterine sarcomas, exenteration may be possible. Exenteration is most often only considered if radiation therapy has been already utilized in the past and no further radiation therapy is possible. Primary exenteration at the time of initial diagnosis, as well as in patients who have not undergone prior radiation, has been reported, but should be reserved for few select cases.

Exenteration was largely abandoned for patients with recurrent ovarian cancers after Barber and colleagues reported a dismal 5-year survival of 7%. However, this report was published in a time prior to effective systemic therapies. Total and/or anterior pelvic exenteration is still not a consideration in the vast majority of patients with newly diagnosed or recurrent ovarian cancers except in exceptional situations (e.g., palliation for a hemorrhaging pelvic tumor not amenable to other palliative measures). In general, palliation is rarely accepted as an indication for exenterative procedures. However, some form of supralevator posterior exenteration (i.e., “modified posterior exenteration”), as well as other bowel resections, are now routinely considered and performed in patients with newly diagnosed and recurrent ovarian cancers. These modified posterior exenterations are not as extensive, and ovarian cancer outcomes are generally quite different from those of the other sites. We will not include these modified posterior exenteration procedures for ovarian cancer in the remainder of the chapter.