Pelvic and Sexually Transmitted Infections

David A. Eschenbach

Recent reports using DNA technology rather than traditional culture methods identify a vast array of previously unrecognized bacterial microbes in the genital tract. The role of these previously unrecognized microbes relative to well-recognized microbes needs further determination for pelvic infections. Many pelvic infections are sexually transmitted (Table 34.1). This chapter provides new data on and updated treatment of pelvic infections.

The impact of infections on women ranges from minor vaginal annoyance to serious illness and, rarely, even death. However, women bear a vast increase in serious consequences of genital infections relative to men. Further, the cost to treat pelvic infections is enormous from both direct medical costs and indirect costs, including time lost from work. Using pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) as an example, previous estimates were that by now, one of every four women who reached reproductive age in the 1970s had an episode of PID. Of women with PID, 25% will be hospitalized, 25% will have major surgery, and 15% will have tubal sterility.

Upper genital tract sites (endometrium, fallopian tubes, ovaries) formerly considered sterile are subject to ascending microbial traffic and occasionally to infection from lower genital tract microbes. Some microbes preferentially infect certain sites and give rise to characteristic symptoms, while other microbes cause few symptoms until major pathologic changes occur or until congenital neonatal infection or male-partner infection ensues. Clinicians should have special knowledge of the infections caused by Neisseria gonorrhoeae; Chlamydia trachomatis; group A and B streptococci; Treponema pallidum; anaerobic bacteria, particularly Clostridia; bacteria associated with bacterial vaginosis (BV); and Mycobacterium tuberculosis, because these infections either are common or produce potentially severe sequelae. Most viral infections of the genital tract are asymptomatic. Several viruses are common and produce severe disease in both adults and neonates, including herpesvirus, cytomegalovirus, hepatitis B virus, human papillomavirus, and HIV.

Vulva

Herpes

Type-specific serologic assays indicate that about 20% of women 14 to 49 years of age are exposed to herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) and almost 60% to herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1). About 60% of women who acquire HSV-2 are asymptomatic, a rate that increases further among those with prior HSV-1 antibody. Despite the frequency of asymptomatic infection, HSV remains a common cause of vulvar ulcers. Infectious genital ulcers also are caused by syphilis and chancroid. HSV ulcers usually occur 2 to 12 days (mean 4) after exposure. Symptomatic primary (first) genital infections typically consist of multiple bilateral vesicles that rapidly ulcerate and can be exceedingly painful. The cervix and vagina also may be involved, producing a gray, necrotic cervix and profuse leukorrhea. External dysuria is common, and bilateral inguinal lymphadenopathy is usual. Vulvar lesions may last up to 3 weeks before healing. Constitutional symptoms of fever, malaise, headache (i.e., aseptic meningitis), and urinary retention (i.e., myelitis) can persist for a week.

After primary infection, HSV becomes latent and localizes in the sacral ganglion and perhaps the dermis. Up to 90% of patients have a recurrence. Additionally, 50% of women have asymptomatic viral shedding, which

occurs on about 3% of days with no symptoms or physical evidence of infection. Most patients develop a secondary symptomatic (recurrent) infection from latent virus weeks to months after the primary infection. Symptomatic recurrence rates increase among women with a severe primary infection. About 50% of patients with recurrence have prodromal symptoms. Secondary lesions usually are less painful, localized, unilateral, and last for a shorter time (3 to 10 days) than primary infection. Systemic manifestations are unusual with secondary infection.

occurs on about 3% of days with no symptoms or physical evidence of infection. Most patients develop a secondary symptomatic (recurrent) infection from latent virus weeks to months after the primary infection. Symptomatic recurrence rates increase among women with a severe primary infection. About 50% of patients with recurrence have prodromal symptoms. Secondary lesions usually are less painful, localized, unilateral, and last for a shorter time (3 to 10 days) than primary infection. Systemic manifestations are unusual with secondary infection.

TABLE 34.1 Sexually Transmitted Infections | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

From 75% to 85% of genital herpes infections are caused by HSV-2, with the remainder caused by HSV-1, the primary cause of oral herpes. The two types of herpes infections are clinically indistinguishable except that genital recurrence is less common following HSV-1. Vesicles and ulcers contain many highly infectious virus particles, and viral shedding occurs until lesions disappear. Thus, direct contact with either genital or oral HSV lesions causes a high rate of infection. Transmission usually occurs by direct contact with ulcerative lesions. Transmission is greatest during a primary infection, intermediate during a secondary infection, and probably least with asymptomatic shedding.

The diagnosis of herpes can be made clinically by finding typical, painful, shallow multiple vulvar ulcers. However, most HSV lesions are atypical. Laboratory confirmation of atypical lesions and lesions that appear during pregnancy is best attained by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) identification or viral culture (which is less sensitive than PCR). Other direct HSV identification methods, including Pap smear, fluorescein tagging, and immunoperoxidase staining, are too insensitive to exclude HSV infection. Type-specific serology uses glucoproteins; gG2 distinguishes HSV-2 from gG1, which signals HSV-1 antibody. Antibodies develop within 3 weeks of HSV infection. However, even high antibody levels do not protect against recurrent HSV infection or the acquisition of HSV, although antibody passively transferred to the fetus offers considerable protection against invasive neonatal infection.

The rising incidence of herpes infection and potentially serious fetal infections makes HSV an important infection in pregnancy. New guidelines for herpes are discussed in Chapter 19.

The following therapies shorten the ulcerative phase of primary infection when used for 7 to 10 days: oral acyclovir (Zovirax), 400 mg three times daily or 200 mg five times daily; famciclovir (Famvir), 250 mg three times daily; or valacyclovir (Valtrex), 1 g twice daily. Antiviral therapy does not eradicate HSV or prevent recurrence. Patients with episodic recurrent herpes should be provided with a supply of drugs to take for 5 days beginning with prodromal symptoms or within a day of the lesion appearance. Patients with six or more yearly recurrences have a 70% reduction in recurrence with the following suppressive therapy when used for up to 1 year: acyclovir, 400 mg twice daily; famciclovir, 250 mg twice daily; valacyclovir, 500 mg daily; or valacyclovir, 1 g daily. The drug expense limits routine or prolonged use. Wet-to-dry therapy for skin lesions is helpful (i.e., 10-minute sitz bath three or four times daily followed by drying with hair dryer), but corticosteroids and antimicrobial ointments actually delay healing. Sexual partners of patients with genital HSV benefit from counseling to prevent contraction of HSV.

Human Papillomavirus

Genital human papillomaviruses (HPVs) are DNA viruses that are distinct from papovaviruses that cause the common wart. Up to 40% of patients have HPV infection that most commonly is subclinical. HPV 6 and 11 cause about 80% of genital warts. Only 1% of HPV-infected women develop visible warts, and only 9% have a history of genital warts. The average incubation period for visible warts is 3 months. Genital warts most often occur on the labia and posterior fourchette (Fig. 34.1). They originally appear as individual lesions, although large confluent growths can occur if neglected. Vaginal and cervical warts are even more common than labial warts; most cervical warts are flat lesions that are visible only by colposcopy. The flat-wart variant is caused by HPV types 16, 18, 31, 33, and 35 (found in 22% of college women tested). A biopsy of flat or atypical-appearing cervical warts is required to exclude cervical

neoplasia. Biopsies of warts also should be performed for pigmented, unresponsive, or fixed lesions or in immunocompromised patients. HPV types 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, and 45 are associated with high-grade cervical dysplasia and cervical cancer, where HPV DNA is integrated into the cancer cell. Women with flat warts should have frequent Pap smears. Routine typing of HPV with the Digene Hybrid Capture II can aid management of women with low-grade or atypical Pap smear interpretations; women with high-risk HPV DNA need referral for colposcopy and possible cervical biopsy, while those with low-risk HPV DNA can receive routine Pap smear testing.

neoplasia. Biopsies of warts also should be performed for pigmented, unresponsive, or fixed lesions or in immunocompromised patients. HPV types 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, and 45 are associated with high-grade cervical dysplasia and cervical cancer, where HPV DNA is integrated into the cancer cell. Women with flat warts should have frequent Pap smears. Routine typing of HPV with the Digene Hybrid Capture II can aid management of women with low-grade or atypical Pap smear interpretations; women with high-risk HPV DNA need referral for colposcopy and possible cervical biopsy, while those with low-risk HPV DNA can receive routine Pap smear testing.

Vulvar warts must be differentiated from the less verrucous, flatter growths of syphilitic condyloma latum (Fig. 34.2) and from carcinoma in situ of the vulva; dark field examination or punch biopsies may be required to differentiate these lesions. Treatment should be guided by available medication, as no regimen is superior to others. Small- to medium-sized verrucous warts usually can be treated with patient-applied podofilox (Condylox), imiquimod (Aldara), or by providers (cryotherapy, podophyllin, or trichloroacetic or bichloroacetic acid). Intralesional interferon and laser surgery represent expensive alternative regimens. Small amounts of podophyllin (0.25 mL) should be used to avoid severe burns. Podophyllin, imiquimod, and podofilox are contraindicated during pregnancy. Large amounts of podophyllin have produced coma in adults and fetal death in pregnancy. A biopsy should be done on atypical lesions before therapy is initiated, because podophyllin causes bizarre histologic changes that persist for months. Vaginal wart treatment or wart treatment in pregnancy is limited to cryotherapy, trichloroacetic acid, or laser ablation. Recurrence rates of 50% probably relate to a failure of these methods to kill the virus in adjacent untreated areas. Severe burns have occurred from the use of 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) to treat warts; as a result, its use is not recommended. Large warts may not respond to surgical or laser removal alone but also may require pretreatment with regional interferon to begin an immune response against HPV. Examination of sexual partners is unnecessary, because most partners already have HPV.

Figure 34.2 Condylomata lata of the vulva and perineum. (From Curtis AH, Huffman JW. A textbook of gynecology, 6th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1950 , with permission.) |

A quadrivalent HPV vaccine 6/11/16/18 viruslike particle that does not contain live virus (Gardasil) has a per protocol efficacy rate of 94% against cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) or adenocarcinoma in situ formation and a per protocol efficacy rate of 95% against external genital wart formation. The per-protocol efficacy rate is the efficacy among ideal candidates (i.e., no prior exposure to these viral types, completed regimen on schedule) and measures protection against disease caused by the types in the vaccine. The vaccine has an excellent safety profile, and it is recommended for the immunization of girls and women 9 to 26 of age in doses at 0, 2, and 6 months. The duration of immunity is unknown. Cervical screening is still needed for those vaccinated because of unrecognized HPV before vaccination and for high-risk HPV genotypes (31, 45) not in the vaccine.

Vestibulitis

Patients with vestibulitis characteristically have pain with vaginal penetration (i.e., intercourse or tampon insertion) and, in extreme cases, pain with sitting or wearing tight clothing. This condition is frequently mistreated as vaginitis because acidic vaginal discharge increases introital

irritation. Patients typically have an erythematous area, most commonly at the 4 o’clock and 8 o’clock positions just outside the hymenal ring. There is no clear evidence that HPV or bacteria cause the inflammation, but an accelerated inflammatory response to Candida is suspected in some patients. Treatment is often not effective, but regimens include topical corticosteroids ointments (i.e., without an alcohol base); local corticosteroid injection; oral tricyclic antidepressants; pelvic floor muscle physical therapy; and in severe cases, skinning vulvectomy.

irritation. Patients typically have an erythematous area, most commonly at the 4 o’clock and 8 o’clock positions just outside the hymenal ring. There is no clear evidence that HPV or bacteria cause the inflammation, but an accelerated inflammatory response to Candida is suspected in some patients. Treatment is often not effective, but regimens include topical corticosteroids ointments (i.e., without an alcohol base); local corticosteroid injection; oral tricyclic antidepressants; pelvic floor muscle physical therapy; and in severe cases, skinning vulvectomy.

Furunculosis

Hair follicles or areas of hidradenitis in the vulva may become infected by staphylococci or other bacteria, giving rise to pustules. Methicillin-resistant staphylococci (MRSA) often cause repetitive and severe recurrences. This condition can be distinguished from herpetic and syphilitic lesions by finding pus within the pustules; confirmation can be made by culture or by finding gram-positive cocci on a Gram stain. If only a few small lesions are present, treatment with hot, wet compresses or hexachlorophene soap helps. If a larger area is involved, administration of antistaphylococcal antibiotics is required until infection subsides, which may take weeks. Daily low-dose suppressive antibiotic therapy (e.g., erythromycin 250 mg) can reduce frequent recurrences. MRSA treatment should include vancomycin or a wide variety of both older and new antibiotics.

Bartholinitis

Two stages of Bartholin gland infection occur. The first is an acute infection of the duct and gland, usually caused by either N. gonorrhoeae or C. trachomatis. If acute infection causes duct obstruction, an abscess can result. Anaerobic bacteria are present in the abscesses. Rarely, diabetics develop synergistic vulvar gangrene from bartholinitis.

Cultures and a Gram stain of material expressed from the duct and detection of gonorrhea and chlamydia should be routine. Acute infection should be treated with regimens that are effective against at least these two pathogens. Patients with an abscess require adequate anesthesia and abscess marsupialization or incision with placement of a catheter in the abscess cavity for 3 to 6 weeks to establish a new duct. Simple incision and drainage has to be avoided because it does not establish mucous drainage by connecting a functioning gland with the introitus. Recurrent infection and mucous cyst formation are common sequelae of bartholinitis; thus, proper marsupialization is critical to prevent sequelae.

Chancroid

The soft chancre of chancroid is a painful ulcer with a ragged, undermined edge and a raised border. In contrast, the syphilitic chancre is painless and indurated. “Kissing ulcers” occur on opposing vulvar surfaces. Tender, unilateral adenopathy is common, and node suppuration occurs in about 50% of patients with lymphadenopathy. The incubation period of this sexually transmitted infection (STI) is 4 to 10 days. The infection is caused by Haemophilus ducreyi, a gram-negative bacterium that forms a school-of-fish pattern on Gram stain preparation. The microbe is fastidious and is best identified by culture of material from aspirated lymph nodes or from the chancre by using special selective media or PCR tests. The differential diagnosis includes syphilis, genital herpes, and lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV). Chancroid is rarely diagnosed in the United States, but it may cause infection in 10% to 40% of genital ulcers in high-STI-risk populations.

Preferred treatment is azithromycin (Zithromax), 1 g orally, or ceftriaxone sodium (Rocephin), 250 mg intramuscularly, in single doses; ciprofloxacin, 500 mg twice daily for 3 days; or erythromycin, 500 mg three times daily for 7 days. Sexual partners should be examined and treated.

Granuloma Inguinale

Granuloma inguinale is rare in temperate climates and usually is considered an STI, although gastrointestinal transmission can occur. Initial papular lesions typically ulcerate and develop into a soft, painless, progressive granuloma that is often covered by a thin, gray membrane. The granuloma may spread over the course of months to involve the anus and rectum. Lymph nodes are moderately enlarged and painless, but they do not suppurate. The infection can become chronic, and long-standing disease may cause genital scarring and depigmentation as well as lymphatic fibrosis with genital edema.

Infection is caused by a gram-negative bacillus, Klebsiella (formerly Calymmatobacterium) granulomatis, which is difficult to culture because it is an intracellular parasite. The identification usually is made from scraped material or a biopsy obtained from the periphery of the lesion. Bipolar-staining bacteria are best identified within mononuclear cells (i.e., Donovan bodies) by Wright or Giemsa staining; no Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved PCR assay is available.

Therapy of choice is a 3-week course of doxycycline, 100 mg; alternatives are trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (double strength), azithromycin, ciprofloxacin, and erythromycin.

Lymphogranuloma Venereum

The incubation period for LGV is 2 to 5 days. Thereafter, a transient, primary, painless genital or anorectal ulcer develops. Multiple, large, confluent inguinal nodes develop 2 to 3 weeks later and eventually suppurate. Acute infection may cause generalized systemic symptoms. If untreated, the infection enters a tertiary phase that can lead to

extensive lymphatic obstruction. This development, together with continued infection, can cause fistulae or strictures of the anal, urethral, or genital areas. Women with LGV are particularly susceptible to rectal stricture. Edema and elephantiasis of the external genitalia and lower extremities are other serious sequelae.

extensive lymphatic obstruction. This development, together with continued infection, can cause fistulae or strictures of the anal, urethral, or genital areas. Women with LGV are particularly susceptible to rectal stricture. Edema and elephantiasis of the external genitalia and lower extremities are other serious sequelae.

The L 1–3 serovars of C. trachomatis produce an acceleration of tissue destruction in vitro and LGV in vivo. The diagnosis of LGV can be confirmed by finding C. trachomatis in genital lesions or lymph nodes by culture or nucleic acid detection. Diagnosis of LGV by serologic testing is not standardized, but the most specific serologic test is the microimmunofluorescent antibody test, in which the specific L immunotypes are identified. Complement fixation (CF) tests are positive in 95% of patients with LGV, but the CF test lacks specificity; test results often are falsely positive from prior infection with the more usual genital serotypes.

LGV responds to 3-week regimens of doxycycline or erythromycin in the usual doses. Large lymph nodes should be aspirated to avoid chronic drainage. Surgical excision of scarred areas may be necessary.

Acute Urethral Syndrome

Dysuria can occur either from urethral or bladder inflammation or from vulvar inflammation. Acute cystitis is present in approximately 50% of women with symptoms of dysuria and urinary frequency. Cystitis is defined by pyuria and a midstream urine culture that contains >105 organisms per milliliter of coliform or staphylococcal bacteria. It is now apparent that about one half of remaining symptomatic women also have cystitis but with <105 coliforms or Staphylococcus saprophyticus bacteria per milliliter of urine. Virtually all women with cystitis have pyuria with eight or more leukocytes per high-power field of urine. Acute urethral syndrome refers to the other 25% of women who have pyuria with recent onset of internal dysuria and urinary frequency but a negative urine culture. These patients usually have C. trachomatis or, less often, N. gonorrhoeae. The remaining 25% of patients with these symptoms have no pyuria, bacteriuria, or chlamydial infection; they have a variety of diseases, including Candida or herpetic vulvitis, vaginitis, and noninfectious diseases. Thus, women with dysuria and no pyuria need a pelvic examination to exclude vulvitis and vaginitis. Treatment of acute urethritis consists of therapy for the infectious agent, whether it is coliform or S. saprophyticus cystitis or C. trachomatis urethritis.

Vaginitis

Vaginitis is the most common reason for a gynecologic visit. Symptoms of vaginitis include increased external dysuria, vulvar irritation and pruritus, vaginal discharge, and a foul odor or yellow discharge color. However, symptoms are very poor indicators of the specific cause of vaginitis. Women with infectious vaginitis have either an STI (i.e., trichomonads) or a quantitative increase in normal flora (i.e., Candida, anaerobes). At least four types of infectious vaginitis are found: candidal, trichomonal, bacterial, and gonococcal (in children). Every effort should be made to establish a specific diagnosis of vaginitis, because a specific diagnosis is mandatory to select a specific and thus effective therapy.

Other conditions that may cause excessive vaginal discharge include cervicitis, normal cervical mucus from cervical ectopy, vaginal foreign bodies (most commonly, retained tampons), and allergic reactions to douching or vaginal contraceptive agents. Atrophic vaginitis among postmenopausal women can produce burning and dyspareunia, but no infectious cause is established.

A small amount of vaginal discharge may be normal, particularly midcycle, when large amounts of cervical mucus produce a clear vaginal discharge. A normal vaginal discharge should not be yellow, have a foul odor, or produce irritation or pruritus.

Examination

External genitalia may be normal or edematous, erythematous, excoriated, or fissured from vaginitis. Local vulvar disease, especially vestibulitis, lichen sclerosis, and lichen planus, must be excluded from the secondary effect of vaginitis.

On speculum examination, the vaginal mucosa may be erythematous. Discharge characteristics that are important to observe are viscosity, floccular appearance, color, and odor. Vaginal pH status must be determined. A pH less than 4.5 indicates either Candida or a normal vaginal discharge. A microscopic examination is necessary, consisting of a normal saline and 10% KOH wet mount. A drop of each solution is mixed with discharge. Before placing a cover glass over the two separate drops, the KOH portion is tested for the presence of a fishy amine odor (KOH odor test). Microscopic examination is made of the saline portion for trichomonads, clue cells and white blood cells (WBCs) with the 400× objective, and of the KOH portion for hyphae with the 100× objective. Multiple causes of vaginitis are frequent.

Vaginal cultures are not particularly helpful except when used selectively to identify Candida. Microscopy is specific but only 80% sensitive to identify various types of vaginitis. When infectious vaginitis is suspected in patients in whom a specific diagnosis cannot be established, a repeat examination should be performed 2 weeks later.

Candidiasis

The most prominent symptom of candidiasis is vulvar and vaginal pruritus. Increased vaginal discharge is infrequent. Vulvar signs may occur, including edema, geographic

erythema, and fissures. Classically, the vaginal walls are red and contain adherent, white, curdy plaques. However, most women with candidiasis have atypical symptoms and little vaginal discharge or erythema.

erythema, and fissures. Classically, the vaginal walls are red and contain adherent, white, curdy plaques. However, most women with candidiasis have atypical symptoms and little vaginal discharge or erythema.

Candida albicans causes about 90% of vaginal yeast infection. Noncandidal species cause the remaining infections. These saprophytic fungi are isolated from the vagina in up to 25% of asymptomatic women. Thus, the mere presence of vaginal Candida does not always identify an infection. Usually large numbers of Candida lead to symptomatic vaginitis. However, severe symptoms also can develop in selected sensitized women with only a few microbes but who have an accelerated immune response to Candida. Candidiasis occurs because changes in host resistance or immune response produce an immunologic response that causes inflammation. The most potent risk factors for candidiasis include pregnancy, diabetes, and use of immunosuppressive drugs and broad-spectrum antibiotics. Frequent vaginal intercourse also can cause candidiasis. Because cellular, not humoral, immunity is required to resist candidal infections, pregnant women and other immunosuppressed patients with decreased cellular immunity are predisposed to candidiasis. Candidal overgrowth also is favored by high urine glucose levels that can occur in diabetes or pregnancy. Broad-spectrum antibiotics cause suppression of the normal vaginal and gastrointestinal bacterial flora, allowing fungal overgrowth. The role of oral contraceptives in candidal infection remains controversial.

Most women have uncomplicated infection defined as sporadic and mild C. albicans infections in those with normal immunity. About 5% of women have complicated infection defined as recurrent, four or more per year; severe, or nonalbicans infection; or infection in pregnant, diabetic or immunocompromised women.

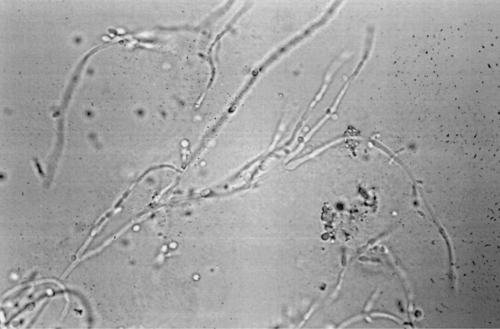

Candidiasis is best diagnosed in KOH wet mounts. Vaginal plaques, vaginal discharge, or vulvar scrapings from the edge of the erythematous border are mixed with 10% KOH (Fig. 34.3). The mycelial form usually is found only during an infection and can be identified by KOH wet mount in 80% of cases. The pH of vaginal discharge is normal (i.e., 4.5 or less). Fungi can readily be isolated on various media. In fact, 50% of women with candidiasis have a negative wet mount but a positive Candida culture. However, Candida is part of normal vaginal flora, and a positive culture does not necessarily indicate infection, so cultures for Candida should be limited to KOH wet mount–negative patients with symptoms or signs of candidiasis.

Local vaginal therapy is used because most antifungal preparations are not absorbed from the intestinal tract. For uncomplicated infection, various intravaginal azole agents used for 1 to 3 days are equally effective for women with infrequent uncomplicated Candida vaginitis. These agents include clotrimazole (Lotrisone), miconazole (Monistat), butoconazole (Femstat), terconazole (Terazol), and tioconazole (Vagistat-1). Azole drugs are not absorbed from the vagina, and these local regimens can be used safely in pregnancy. The insertion of a capsule containing boric acid powder into the vagina for 7 days also is effective but should not be used in pregnancy. A one-time dose of fluconazole (Diflucan), 150 mg orally, or itraconazole (Sporanox),

400 mg initially and then 200 mg for 2 days, is effective for uncomplicated infection. Patients with complicated infection or severe symptoms need 7 to 14 days of intravaginal azole therapy or fluconazole, 150 mg with one to two repeat doses every 3 days. Oral nystatin administration to decrease gastrointestinal colonization does not markedly improve therapeutic cure rates or diminish recurrence rates. The 15% of male sexual contacts of women with candidiasis with symptomatic balanitis should be identified and treated to prevent recurrent female infection. In addition, some women with candidiasis have other concurrent vaginal infections that may be clarified by a repeat physical and wet mount examination.

400 mg initially and then 200 mg for 2 days, is effective for uncomplicated infection. Patients with complicated infection or severe symptoms need 7 to 14 days of intravaginal azole therapy or fluconazole, 150 mg with one to two repeat doses every 3 days. Oral nystatin administration to decrease gastrointestinal colonization does not markedly improve therapeutic cure rates or diminish recurrence rates. The 15% of male sexual contacts of women with candidiasis with symptomatic balanitis should be identified and treated to prevent recurrent female infection. In addition, some women with candidiasis have other concurrent vaginal infections that may be clarified by a repeat physical and wet mount examination.

The number of nonalbicans candidal infections appears to have increased. Such infections respond poorly to azole therapy, including fluconazole. Vaginal boric acid or nystatin (100,000 U) therapy works best, but nystatin is no longer commercially available. A gentian violet 1% aqueous solution is a poor second choice.

Patients with frequently recurrent candidiasis represent the most difficult problem in treatment. Extended 2- to 3-week female therapy, male therapy, and reduction of sugar intake usually are ineffective. A glucose tolerance test and HIV testing should be performed in recurrent or resistant cases to exclude unrecognized diabetes and HIV infection. However, these tests are seldom positive.

Complicated infection from frequently recurrent candidiasis (four or more times a year) should be treated first with standard anti-Candida therapy for 2 weeks, followed by suppressive therapy with intravaginal azole or boric acid twice weekly; an intravaginal azole daily for 5 days once monthly; oral fluconazole, 150 mg weekly; or oral itraconazole, 400 mg monthly. Suppressive treatment should continue for at least 6 to 12 months; recurrent candidiasis usually is reduced to zero to one infection yearly, but 30% to 40% of patients develop frequent recurrence of Candida on cessation of therapy.

Trichomoniasis

Characteristic symptoms of trichomoniasis include a profuse, yellow, malodorous vaginal discharge, often with uncomfortable vulvar irritation. Trichomonas vaginalis is a common STI, present in 3% to 15% of asymptomatic women and in up to 20% of women who attend clinics for STIs. T. vaginalis is most likely identified in symptomatic women with recent acquisition. However, about 50% of all women with T. vaginalis are asymptomatic. Most male contacts of women with trichomoniasis carry the microbe asymptomatically in the urethra and prostate.

The classic profuse, frothy, yellow vaginal discharge is present in only about one third of women. The vulva may be edematous and inflamed by inflammation from the discharge. Rarely, subepithelial redness of the cervix (i.e., strawberry cervix) is seen with the naked eye; smaller red areas are more commonly identified colposcopically. The discharge in women with symptomatic trichomoniasis usually has a pH greater than 4.5 and forms an amine odor with 10% KOH. Motile trichomonads are demonstrated in the saline wet mount smear (Fig. 34.4). Trichomonads are larger than WBCs and have a jerky motility. The wet mount usually also contains many polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Although the wet mount can identify trichomonads with 80% sensitivity among symptomatic women, less than 50% of all women identified with T. vaginalis by culture have positive wet mounts. Trichomonads also are occasionally seen on a Pap smear.

T. vaginalis is an anaerobic protozoan. A culture of this microbe is easy to perform. A commercially available medium is the InPouch (BioMed Diagnostics, White City, OR) device. Culture should be limited to cases where the diagnosis is suspected but cannot be confirmed by wet mount. Screening cultures are not recommended in asymptomatic women except for select high-risk populations. Women with T. vaginalis also should be cultured for N. gonorrhoeae because of the close association between microbes.

T. vaginalis resides not only in the vagina but also in the urethra, bladder, and Skene glands of women, so systemic, rather than local, therapy is required. The recommended regimen is 2 g of either metronidazole or tinidazole in one dose because of complete patient compliance and high effectiveness. A 7-day, 500 mg twice daily metronidazole course does not increase the 95% cure rate of a single

dose. Simultaneous treatment of the male sexual partner is recommended. Recurrent trichomoniasis usually is attributable either to a lack of compliance or to sexual reexposure to an untreated partner. A single recurrence should be treated with the recommended regimens. However, increasing in vitro and in vivo resistance of T. vaginalis to metronidazole exists, and repeated treatment failure should be treated with metronidazole, 2 g daily for 3 to 5 days. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has consultation available for patients who fail this regimen.

dose. Simultaneous treatment of the male sexual partner is recommended. Recurrent trichomoniasis usually is attributable either to a lack of compliance or to sexual reexposure to an untreated partner. A single recurrence should be treated with the recommended regimens. However, increasing in vitro and in vivo resistance of T. vaginalis to metronidazole exists, and repeated treatment failure should be treated with metronidazole, 2 g daily for 3 to 5 days. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has consultation available for patients who fail this regimen.

Metronidazole therapy has slight controversy because of tumor-causing potential. In animals, large (equivalent to 350 to 1,000 human) doses cause tumors. However, increased tumor rates were not found in a small series of women evaluated for up to 10 years after metronidazole therapy, but larger studies are needed. Metronidazole is a category B drug, and it can be used for symptomatic infection in pregnancy. A meta-analysis showed no consistent evidence of teratogenesis with metronidazole use in pregnancy. However, because treatment of asymptomatic T. vaginalis has not reduced and may even increase prematurity, asymptomatic women should not be treated in pregnancy. Persistent discharge after adequate treatment for trichomoniasis should lead to repeat examination for Trichomonas, candidiasis, and gonorrhea.

Bacterial Vaginosis

BV describes the vaginal condition resulting from overgrowth of both a variety of anaerobic bacteria and to a lesser degree of Gardnerella vaginalis. Recently, a wide variety of difficult-to-culture bacteria were found by DNA technology to be the predominant microbes in BV. These microbes are normal inhabitants of the vagina, but overgrowth of the normal Lactobacillus-dominant flora by these bacteria causes BV, which results in a thin, homogeneous, fishy-smelling, gray vaginal discharge that adheres to the vaginal walls and often is present at the introitus. In contrast to findings in other causes of vaginitis, the vaginal epithelium appears normal, and WBCs usually are not present. The fishy amine odor produced by anaerobes is accentuated when 10% KOH is placed on the discharge.

The diagnosis of BV is based on the presence of three of the following four characteristics of the vaginal discharge: pH greater than 4.5, a homogeneous thin appearance, a fishy amine odor with the addition of 10% KOH, and clue cells. Clue cells are vaginal epithelial cells with so many bacteria attached to the cell border that it is obscured. In BV, 20% to 50% of the epithelial cells are clue cells. Polymorphonuclear leukocytes and lactobacilli are notably absent. Gram stains used for diagnosis rely on a reduction in Lactobacillus morphotypes and an increase in small gram-negative rods and gram-positive cocci. Commercially available point-of-care tests for high concentrations of G. vaginalis (Affirm), pH and trimethylamine (FemExam), pH and amines (QuickVue Advance), sialidase (OSOM BV Blue), and proline aminopeptidase (PIP Activity Test Card) are available. Routine vaginal cultures are not helpful, because the microbes implicated in BV can either be recovered from women without BV (40% of asymptomatic women without vaginitis carry G. vaginalis) or not recovered in those with BV. Instead, the microbiology of BV is distinguished by the 10- to 1,000-fold increased concentration of anaerobic bacteria compared with that found in normal vaginal flora.

Factors leading to the overgrowth of these microbes are poorly established but include the absence of Lactobacillus. Sexual transmission is a risk factor suggested by the association of BV with a new sexual partner, more than one partner, and shared sex toys among female partners.

Treatment is not advocated for most asymptomatic women with BV, as it can spontaneously disappear. However, the increased concentration of potentially virulent bacteria in the vagina is related to upper genital tract infection following surgery. A significant, increased relative risk (RR) of postoperative infection was reported in patients with BV following cesarean section (RR 6), hysterectomy (RR 3 to 4), and induced abortion (RR 3). BV also is associated with PID and postpartum endometritis after vaginal delivery. Treatment of BV is particularly beneficial for women who are undergoing elective surgery. BV in pregnancy also is related to premature delivery (RR 2 to 4), amniotic fluid infection (RR 2 to 3), and chorioamnionitis (RR 2 to 3); treatment of women with prior preterm delivery has reduced the incidence of preterm delivery, but treatment of low-risk asymptomatic women to date has had no effect on preterm delivery.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree