22 Pediatric Plastic Surgery

Craniofacial Anomalies

Craniofacial Embryology

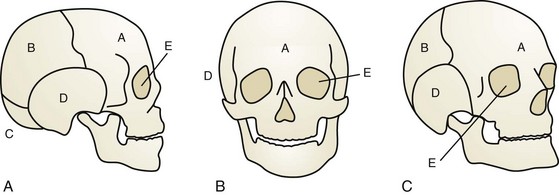

The neurocranium consists of plates that ultimately become the adult frontal, occipital, sphenoid, ethmoid, paired temporal, and paired parietal bones (Fig. 22-1). They are separated by sutures and fontanelles that serve two main purposes: to allow molding of the head as it passes through the birth canal in parturition, and to allow rapid increase of brain volume, which doubles in the first 6 months of life and again by 2 years of age.

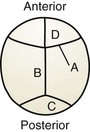

The longitudinal suture between the paired parietal bones is the sagittal suture. Anteriorly, the sagittal suture becomes anterior fontanelle where it intersects the transverse coronal sutures that separate the frontal bones from the parietal bones. Posteriorly, the sagittal suture becomes the posterior fontanelle where it meets the oblique L-shaped lambdoid sutures. Finally, the metopic suture runs longitudinally between the two paired frontal bones (Fig. 22-2). Closure of the posterior fontanelle occurs within the first 6 months of life, whereas the anterior fontanelle closes between 12 and 18 months of age. The metopic suture closes at about 7 months of age, and completely fuses such that the adult frontal bone has no evidence of a former metopic suture. The sagittal and coronal sutures are next to fuse, in a posterior-to-anterolateral direction. Prenatal or postnatal premature fusion is called craniosynostosis, which causes abnormal skull shape by restricting growth in the direction of the fusion, which can sometimes lead to pressure on the growing brain.

Figure 22-2 Cranial sutures as viewed from the vertex of the skull. A, coronal; B, sagittal; C, lambdoidal; D, metopic.

Cleft Lip, Nose, and Palate

Cleft lip, nose, and palate are the most frequent presentations of orofacial clefts, which are the most common congenital birth defects in the United States, estimated to be 1 in 590 live births annually (Basseri, 2011; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2006; Parker, 2010) (Table 22-1). Approximately 1 in 700 individuals in the United States is affected, or about 15,000 live births per year. Although the cleft may be a component of an identifiable syndrome, it more commonly occurs as a solitary nonsyndromic defect. The clefting of the lip always affects the shape of the nose as well. Facial clefting is frequently categorized into cleft lip with or without cleft palate (CLP) and the isolated cleft palate (CP). Epidemiologically, a distinction is notable between the two with respect to incidence, race, and sex. Approximately 1 in 700 live births is affected with a CLP, occurring twice as often in males. Asians constitute the largest population of affected infants, followed by the white population, and then African Americans. CP has a lower incidence of approximately 1 in 1000 live births, with slightly more females affected, but no ethnic predilection.

Table 22-1 Clefting Characteristics

| Cleft Lip/Nose + Cleft Palate | Isolated Cleft Palate | |

|---|---|---|

| Incidence | 1 in 700 | 1 in 1500 |

| Sex | M > F (2 : 1) | F > M (3 : 2) |

| Race | Asian > Caucasian > African (4 : 2 : 1) | No difference |

| Syndromic association | 15% | 50% |

Embryologically, at the end of the fifth week the maxillary prominences grow medially, and the medial nasal prominences are displaced toward the midline, where they fuse and ultimately form the premaxilla, which contains the philtrum of the upper lip, the portion of the upper jaw carrying the incisors, and the triangular primary (anterior) palate. Simultaneously, maxillary prominences develop outgrowths called the palatine shelves, which fuse in the midline, forming the secondary (posterior) palate. The primary and secondary palates join at the incisive foramen to separate the nasal and oral cavities. Failure of fusion of the palatine shelves results in secondary palatal clefting, whereas partial or complete lack of fusion of the maxillary prominence with the medial nasal prominence on one or both sides results in lip clefting with or without clefting of the primary and secondary palates (Fig. 22-3). This developmental cascade is complete by the 12th week of gestation. During this vulnerable period anatomic interference (malposition of the tongue due to mandibular hypoplasia, as in Pierre Robin sequence), miscues in cell differentiation and migration, or teratogens (phenytoin, retinoids, steroids, lithium, and maternal smoking) may lead to clefting in the developing fetus.

Deformational Plagiocephaly

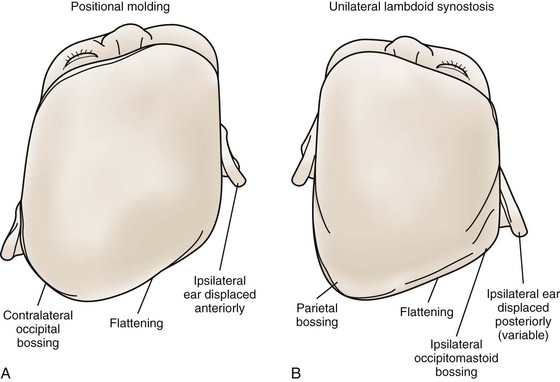

Right-sided deformational plagiocephaly is more common, possibly due to right-handed mothers holding infants in a right-side-down position to nurse, causing pressure and flattening of the right occiput. Regardless of the side, once a preferential supine position develops, it becomes habitual and difficult to correct. History usually confirms a normal head at birth and acquired asymmetry that worsens with time. As the occiput becomes flatter, up to 80% of infants will have anterior displacement of the ipsilateral forehead, with concomitant increase in the height of the ipsilateral palpebral fissure, anterior displacement of the ipsilateral ear, and anterior displacement of the ipsilateral cheek, which can be seen from the anterior view (Fig. 22-4). These changes are shaped like a parallelogram on vertex view (Fig. 22-5). Posteriorly, the mastoid skull bases should be symmetric, otherwise there would be suspicion for a true unilateral lambdoid synostosis, described in The Skull, later.

The Skull

The growth of bone can be visualized as occurring at the sutures in a direction perpendicular to the suture’s axis. Therefore when a suture is fused and normal growth is interrupted, resulting compensatory growth is in the direction parallel to the suture, resulting in characteristic skull shapes with their own Greek descriptive terms. So a sagittal craniosynostosis results in abnormal growth parallel to the fused sagittal suture leading to anteroposterior elongation and temporal narrowing, resulting in a scaphocephaly, or “boat-shaped head.” Simple craniosynostosis refers to single suture fusion, whereas complex craniosynostosis is multiple suture fusion (Table 22-2).

Table 22-2 Skull Shape Nomenclature

| Name | Suture(s) Involved | Shape |

|---|---|---|

| Acrocephaly | Bilateral coronal | Skull height greater anteriorly, slanting downward posteriorly |

| Brachycephaly | Bilateral coronal | Wide, taller skull shortened in anteroposterior dimension |

| Oxycephaly | Bilateral coronal | Taller skull, shortened width and anteroposterior dimension |

| Turricephaly | Bilateral coronal | Tall skull |

| Plagiocephaly | Unilateral coronal or unilateral lambdoidal | Asymmetrical skull |

| Scaphocephaly | Sagittal | Anteroposterior elongation with bitemporal narrowing |

| Trigonocephaly | Metopic | Narrow, triangular, ridged forehead |

| Kleeblattschädel | Bilateral coronal, lambdoidal, and metopic | Cloverleaf deformity |

Nonsyndromic, Simple Craniosynostoses

Sagittal Synostosis

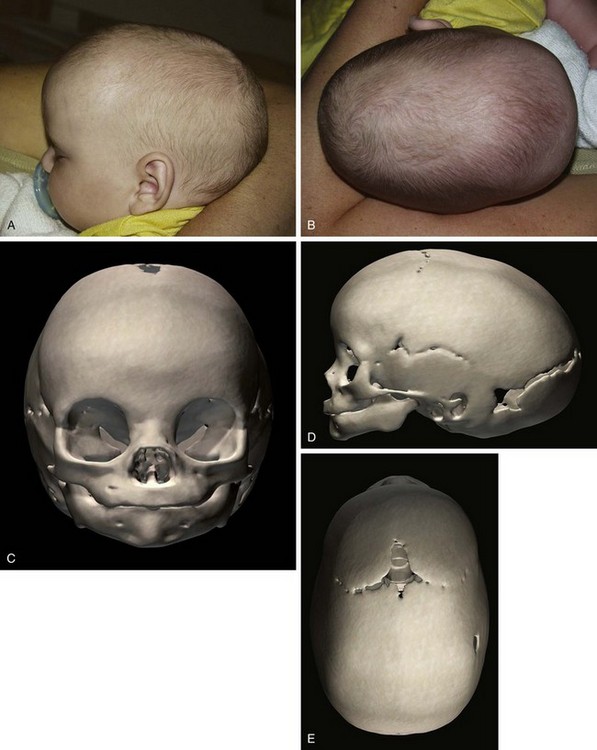

Sagittal synostosis, the premature fusion of the sagittal suture, leads to increased anteroposterior length and biparietal narrowing, known as scaphocephaly (Fig. 22-6). Isolated nonsyndromic sagittal synostosis is the most common form of craniosynostosis. It is almost always sporadic, with only 2% of patients having a genetic etiology. A 4 : 1 male predominance is recognized, with no race predilection. There is low risk for ICH and abnormal brain development, as the remaining cranial sutures allow compensatory expansion of the neurocranium.

Metopic Synostosis

The metopic suture is the first cranial suture to fuse, typically at about 7 months of age. It is the only suture that disappears and is indiscernible in the adult skull. Significantly premature fusion leads to a “keel”-shaped, trigonocephalic head (Fig. 22-7). Metopic synostosis has an incidence of between 1 : 2500 and 1 : 15,000 births, accounting for 10% to 20% of isolated craniosynostoses. Males are affected more often than females at about 3 : 1. Physical examination shows the keel-shaped forehead with hypotelorism, upward slanting of the eyelids laterally, and a triangular shape to the forehead and supraorbital ridge. Although typically isolated, 8% to 15% of children affected with trigonocephaly will have associated anomalies involving the extremities or the central nervous, cardiac, or genitourinary system.

Lambdoid Synostosis

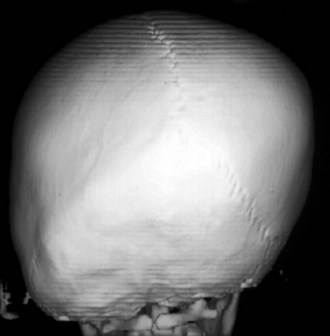

Lambdoid synostosis may involve one or both of the lambdoid sutures and is the rarest of the craniosynostoses. When it occurs, it is usually unilateral and causes a synostotic posterior plagiocephaly. A raised ridge may be palpable over the involved suture, and there is often a mastoid bulge of the affected side of the occiput with contralateral parietal bossing (Fig. 22-8). From the vertex view (see Fig. 22-5), a trapezoid head shape is seen, with contralateral frontal bossing, posterior displacement of the ipsilateral ear, and ipsilateral occipitomastoid bossing. This view best distinguishes rare true lambdoid suture synostosis from common deformational plagiocephaly. True lambdoid craniosynostosis requires cranial vault remodeling, whereas deformational plagiocephaly is treated by positioning or helmet therapy.

Coronal Synostosis

Synostosis of a single coronal suture results in a widened ipsilateral palpebral fissure, an elevated and anteriorly positioned ipsilateral ear, nasal root deviation toward the affected suture, chin deviation away from the affected suture, and a superiorly and posteriorly displaced supraorbital rim and eyebrow known as the “harlequin eye” deformity (Fig. 22-9). Bilateral craniosynostosis restricts anteroposterior growth and causes retrusion of the fronto-orbital region, leading to compensatory widening and raised height of the anterior cranium; the result is described as brachycephaly, acrocephaly, oxycephaly, or turricephaly (Table 22-2). In bilateral craniosynostosis, there is increased incidence of ICH.

Syndromic, Complex Craniosynostoses (Table 22-3)

Table 22-3 Gene Mutations Associated with Craniofacial Syndromes

| Gene/Protein | Syndrome | Chromosome |

|---|---|---|

| FGFR1 | Pfeiffer | 8 |

| FGFR2 | Apert | 10 |

| Crouzon | 10 | |

| Pfeiffer | 10 | |

| Jackson-Weiss | 10 | |

| Beare-Stevenson | 10 | |

| FGFR3 | Muenke | 4 |

| Crouzon with AN | 4 | |

| TWIST | Saethre-Chotzen | 7 |

| Treacle | Treacher Collins | 5 |

AN, acanthosis nigricans; FGFR, fibroblast growth factor receptor.

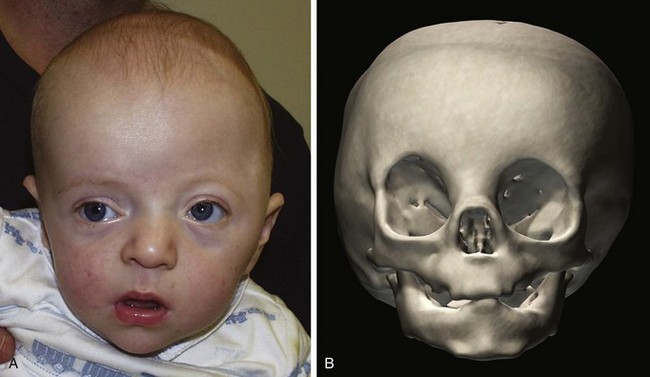

Apert Syndrome

Apert syndrome is autosomal dominant with incomplete penetrance and a birth prevalence of 5.5 to 16 per 1 million live births. The majority of cases are sporadic; more than 98% of patients with Apert syndrome have identifiable mutations in the FGFR2 gene, resulting in multiple anomalies in all systems (Fig. 22-10). Two distinguishing features include symmetric complex syndactylies of the hands and feet, and cognitive defects.

| Apert Syndrome: Features and Findings |

|---|

| Craniofacial |

< div class='tao-gold-member'> Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|