16 Pulmonary Disorders

Physical Examination

Inspection

Decreased subcutaneous adipose tissue as seen in a patient with cystic fibrosis should be noted. The pattern of breathing should always be evaluated with the child disrobed. Any use of expiratory musculature is abnormal. Suprasternal and intercostal retractions reflect excessive negative pleural pressure and can be seen in normal children with thin chest walls after vigorous exercise. Subcostal retractions are always pathologic and are the result of hyperinflated lungs and a flattened diaphragm pulling inward on the chest wall. In advanced lung disease the use of accessory muscles of inspiration can be noted; the sternocleidomastoid muscle, for example, helps lift the chest (in a “bucket handle” fashion) and increase its anteroposterior diameter, thereby increasing intrathoracic volume. In respiratory muscle fatigue, a pattern of breathing can be observed in which the diaphragm alternates with the intercostal muscles to inflate the lungs. This is known as respiratory alternans and is seen as alternating abdominal and chest expansion instead of the usual pattern of simultaneous chest and abdominal expansion. Chest wall deformities such as pectus excavatum or pectus carinatum (see Chapter 17) should be noted.

Auscultation

Other sounds that can be heard include friction rubs, which are creaking sounds heard during both phases of respiration as inflamed pleural surfaces rub over one another. One of the most important abnormal findings in children is the absence of breath sounds over an area of collapse or consolidation. Phase delay in air entry (such as in unilateral bronchial obstruction) can be detected only with a differential (double-headed) stethoscope (Fig. 16-1).

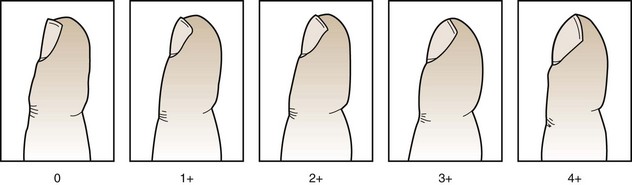

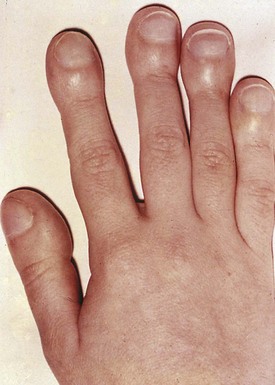

The notion that the examination of the lungs begins at the fingertips is an important one, as digital clubbing may point to the presence of lung disease. Various stages of clubbing, from mild to severe, are depicted in Figures 16-2 and 16-3. Not all digital clubbing is associated with pulmonary disease (Table 16-1); nonpulmonary causes include cardiac, inflammatory, gastrointestinal, hepatic, and familial, as well as clubbing observed with thyrotoxicosis. Bronchiectasis from cystic fibrosis or from other chronic infectious causes is the major cause of clubbing among all pulmonary diseases. Digital clubbing in any child with a chronic cough or wheezing warrants a thorough evaluation and investigation to determine the underlying disorder.

| Pulmonary |

| Cardiac |

| Gastrointestinal or Hepatic |

| Familial |

| Thyrotoxicosis |

The astute pulmonologist will carefully examine the remainder of the patient. The examination should also include evaluation for nasal polyps (see Fig. 16-30), which can be associated with cystic fibrosis, triad asthma, or significant atopy. An increased second heart sound could suggest pulmonary hypertension.

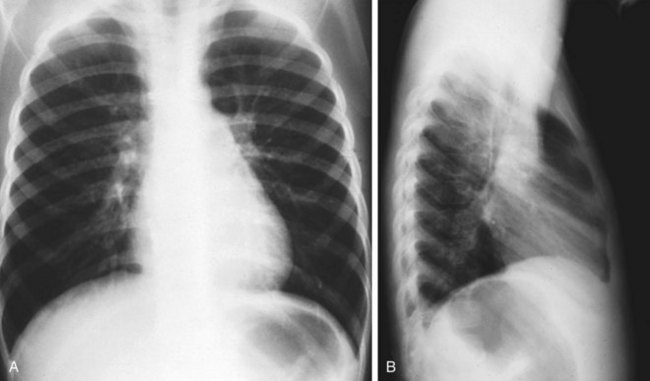

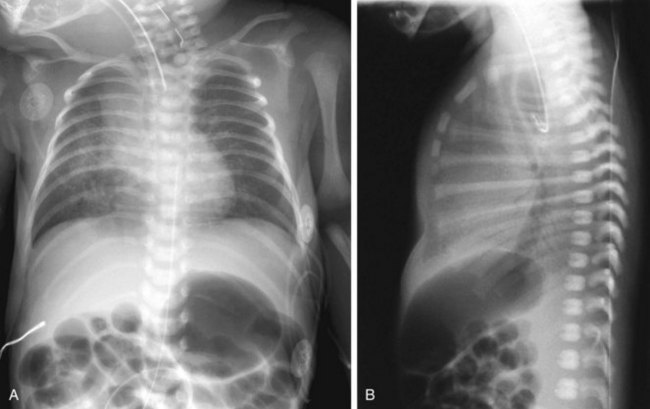

Radiology

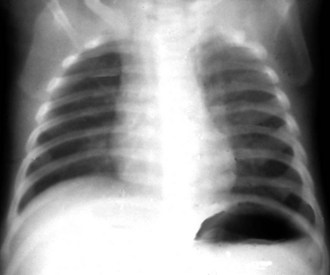

The pediatric chest radiograph is unique in that normal findings may vary with age. The width of the chest on the lateral projection in the chest radiograph of a normal infant (Fig. 16-4) is about the same as the transverse dimension on a frontal projection, and the lungs may appear relatively radiolucent. Further, in contrast with the older child (>2 years of age), the cardiothoracic ratio in the infant normally may be as high as 0.65. The width of the superior mediastinum at this age may also be striking because the thymic shadow is particularly prominent during the first few months of life before the normal process of involution occurs. The normal chest radiograph of an older child (Fig. 16-5) shows the diaphragm on an inspiratory film at the eighth or ninth rib posteriorly (sixth rib anteriorly), a cardiothoracic ratio of 0.5, and pulmonary vessels extending two thirds of the way to the periphery. In most situations a lateral radiograph should accompany the posteroanterior (PA) view because some pathologic findings may be missed on a single projection. For example, a lateral examination yields the best information about the anterior mediastinum and the tracheal air column and may reveal a small pleural effusion that is unsuspected on the basis of a PA radiograph alone. In combination with the PA view, the lateral projection may help localize an abnormal finding to a particular lobe or segment or document hyperinflation with diaphragmatic flattening (Fig. 16-6). In most situations the chest radiograph taken at full inspiration is most helpful. In the evaluation for bronchial foreign bodies, a comparison of inspiratory and expiratory views (or left and right lateral decubitus films in the younger patient) can help if one lung is unable to empty. In looking for a small pneumothorax, the expiratory film is more helpful because the smaller lung volume allows extrapulmonary air to expand to become more evident.

Figure 16-4 Normal posteroanterior chest radiograph in a 1-month-old infant.

(Courtesy Beverly Newman, MD, Pittsburgh, Pa.)

Cough

Persistent or recurrent cough represents one of the most common and vexing problems in pediatrics. In most circumstances the tracheobronchial tree is kept clean by airway macrophages and the mucociliary escalator, but cough becomes an important component of airway clearance when excessive or abnormal materials are present, or when mucociliary clearance is reduced, as during a viral respiratory illness. A cough clears airway secretions and inhaled particulate matter through a combination of the high airflow velocities generated during the expiratory phase of the cough and compression of smaller airways, which “milks” the secretions into larger bronchi where they can be eliminated by a subsequent cough. Cough is generally produced by a reflex response arising from irritant receptors located in ciliated epithelia in the lower respiratory tract, but it can be suppressed or initiated at higher cortical centers. One of the most common causes of cough in pediatric patients is the self-limited cough of an acute viral lower respiratory illness or bronchitis that lasts 1 to 2 weeks. The cough that persists longer than 2 weeks is potentially more worrisome. A diagnostic approach to chronic cough is best served by considering the age of the child (Table 16-2).

Table 16-2 Causes of Cough according to Age

| Infancy (Younger Than 1 Year) |

| Congenital and Neonatal Infections |

| Congenital Malformations |

| Other |

| Preschool |

| School Age to Adolescence |

| All Ages |

CMV, cytomegalovirus; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus.

Age and Cause

Infancy (Younger Than 1 Year)

Cough starting at birth or shortly afterward may be a sign of serious respiratory disease and must be evaluated assiduously. Cough beginning at this time raises the possibility of congenital infections, such as cytomegalovirus or rubella, which are often associated with other findings, such as hepatosplenomegaly, thrombocytopenia, or central nervous system disease. Pneumonia due to Chlamydia trachomatis (Fig. 16-7) generally develops after the first month of life and presents as an afebrile pneumonitis with congestion; wheezing; fine, diffuse crackles; a paroxysmal cough; and, in approximately 50% of cases, a prior or concomitant inclusion conjunctivitis. Pneumonia caused by Bordetella pertussis is a potentially life-threatening illness characterized by severe paroxysmal coughing episodes followed by cyanosis and apnea and is often associated with an inspiratory “whoop.” The latter finding may be missing in young infants or those weakened by the recurrent coughing spasms. Newborns and young infants may have apnea as the primary sign of a B. pertussis infection. The chest radiograph is nondiagnostic and can be normal or (Fig. 16-8) show perihilar infiltrates; atelectasis; hyperinflation; and, in some cases, interstitial or subcutaneous emphysema. A high white blood cell count with a predominance of lymphocytes supports the diagnosis, but unfortunately once the patient has passed through the usually innocent-appearing coryzal stage into the paroxysmal stage, diagnostic tests have a lower yield. Diagnostic approaches to whooping cough include detection of B. pertussis DNA by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and serologic detection of B. pertussis–specific IgM or IgA. Ureaplasma urealyticum and Pneumocystis jirovecii (formerly known as P. carinii) have been recognized as causes of pneumonia and persistent cough in this age group.

Figure 16-7 Pneumonia caused by Chlamydia trachomatis in a 3-month-old infant with inclusion conjunctivitis.

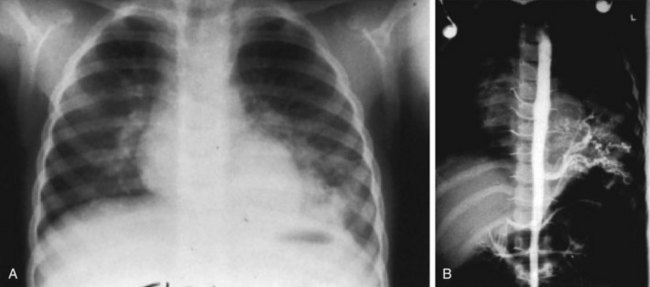

Congenital malformations, such as tracheoesophageal fistula (Fig. 16-9) and laryngeal cleft or web, can produce cough via chronic aspiration of gastric contents, milk, or saliva. These anomalies are associated with feeding-related coughing, choking, and occasional cyanosis. Hypoxemia may persist between feedings. Infants with neurologic disorders may have incoordination of swallowing and sucking reflexes that lead to aspiration of milk or gastric contents into the lung. Pulmonary sequestration (in which a portion of the lung is perfused by systemic, not pulmonary arteries) (Fig. 16-10) and bronchogenic cysts (cystic structures arising from the pulmonary epithelium) are rare congenital anomalies that may compress the pulmonary tree or become infected, thereby producing a cough. Aberrant major blood vessels generally cause inspiratory stridor and expiratory wheezing from tracheal compression (Fig. 16-11; see also Fig. 16-25), but a brassy cough may also be observed, as may dysphagia from the associated esophageal compression.

Figure 16-11 Vascular ring. Barium swallow in a toddler with posterior compression of esophagus and trachea from a vascular ring.

(Courtesy Department of Radiology, Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pa.)

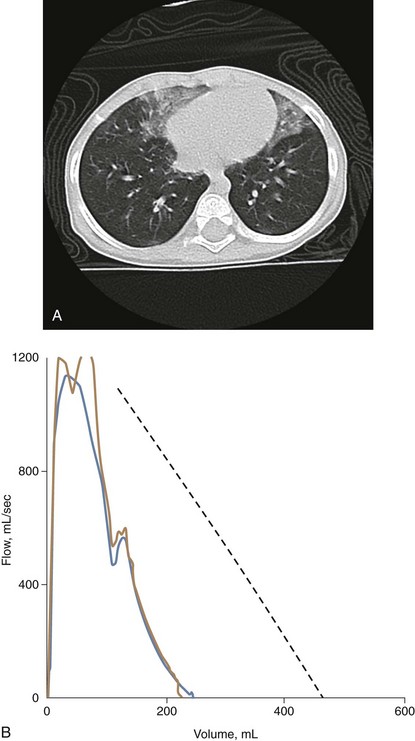

The diagnosis of a specific chILD is usually made subsequent to lung biopsy, but this is usually preceded by a variety of less invasive tests (Fig. 16-12) such as a high-resolution computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest, infant lung function testing, and flexible fiberoptic bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage. Surfactant disorders (surfactant protein B or C deficiencies, or ABCA3 mutations) can often be diagnosed by mutation analysis. The prognosis of chILD can be quite variable, with some universally fatal (alveolar capillary dysplasia) or very severe and treatable only by lung transplantation (surfactant protein B deficiency), and some showing gradual improvement over months or years (neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia of infancy).

Preschool

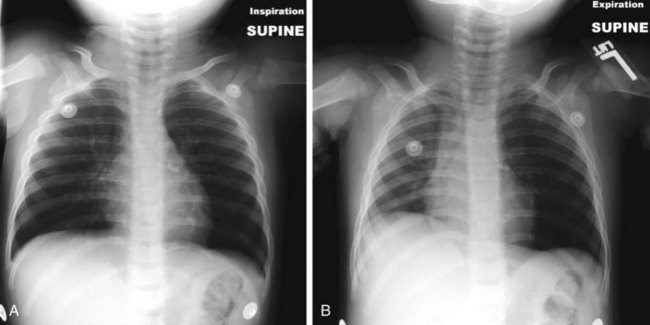

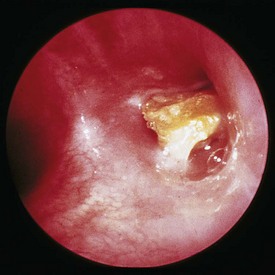

An inhaled foreign body in either the tracheobronchial tree or esophagus is an important cause of chronic cough, especially in toddlers. A history of gagging or choking may be absent at this age, physical examination may be unrevealing, and the plain chest radiograph may be normal. Subtle differences in air entry into homologous lung segments, detected with the differential (double-headed) stethoscope (see Fig. 16-1), may be the only indication of a foreign body in the airway. Cough is present in more than 90% of cases; it is usually of abrupt onset, but a quiescent period may occur after inhalation and cough may disappear as irritant receptors adjust to the object’s presence. A mobile foreign body may result in the recurrence of cough as new receptors are stimulated by the object. Although inspiratory and expiratory radiography and fluoroscopy are useful in the evaluation of a child with a possible bronchial foreign body, they may be normal and rigid bronchoscopy may be necessary to confirm or disprove the presence of a foreign object (Fig. 16-13). Unilateral air trapping demonstrated by inspiratory and expiratory radiographs (Fig. 16-14, A and B) (or left and right lateral decubitus films in younger children) strongly suggests an inhaled foreign body.

Figure 16-13 Foreign body. Portion of a carrot lodged in the right mainstem bronchus, as seen through a rigid bronchoscope.

(Courtesy S. Stool, MD, Pittsburgh, Pa.)

Suppurative lung diseases, such as cystic fibrosis or bronchiectasis (Fig. 16-15), or deriving from any other causes (e.g., tuberculosis), characteristically result in a chronic cough producing purulent sputum. “Right middle lobe syndrome,” commonly associated with enlargement of lymph nodes surrounding the right middle lobe bronchus in tuberculosis, has also been described in asthma and a number of other illnesses and may be associated with chronic cough. Recurrent infection of the middle lobe can ultimately lead to the development of bronchiectasis or fibrosis.

School Age to Adolescence

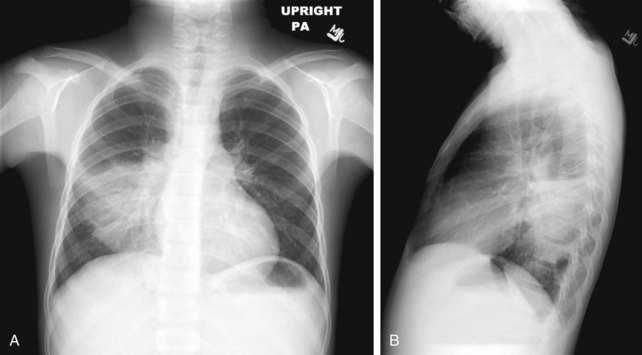

Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection is an important cause of chronic cough among school-age children. In its early stages, the disease is identical to a viral upper respiratory infection with coryza, sore throat, low-grade fever, and malaise. Gradually, the symptoms of lower respiratory involvement emerge and persist. Cough ranges from dry and hacking to one productive of mucoid sputum. On occasion the disease progresses to lobar pneumonia (Fig. 16-16, A and B) indistinguishable from typical bacterial pneumonia. The cough typically persists for 6 weeks, although it may last for 3 months. Physical findings tend to be minimal, although crackles and wheezing are often noted. The chest radiograph is not diagnostic, and the findings may be either interstitial or bronchopneumonic in character, with predilection for the lower lobes (see Fig. 16-16, A and B). Often the chest radiograph is normal. Diagnosis of M. pneumoniae infection can be made most rapidly by throat swab PCR. Serology is also used, and either paired sera for IgG titer or a single elevated IgM titer can be diagnostic. Mycoplasma culture is performed, but the organism is difficult and slow to isolate (taking 60 to 90 days), making this test of little clinical utility.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree