Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology

Ann J. Davis

Pediatric and adolescent gynecology is frequently viewed as a single focused aspect of gynecology. In fact, these two areas are reasonably distinct, with a logical division being at the onset of puberty and the activation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–ovarian (HPO) axis. Prepubertal girls differ from postpubertal girls in anatomy, etiologies of similar symptoms, and the spectrum of likely and common syndromes. However, both groups require specific and different communication skills. Psychosocial and developmental milestones and characteristics help to guide the obstetrician and gynecologist in how to communicate with each age group in an effective manner. Involvement of the family or adult caretaker also is critical in achieving the goals of providing excellence in gynecologic care. This chapter will discuss topics in both of these age groups, with an emphasis on the differences in children and teens as compared with those of mature reproductive women.

Examination

The Prepubertal Child

The genital examination of the prepubertal child should be approached quite differently from the gynecologic examination of an adolescent or adult. However, the complete exam may include all of the same elements as the examination of the more mature reproductive female: examination of the external genitalia, examination of the vagina, and palpation of the uterus and adnexal structures.

External Genitalia

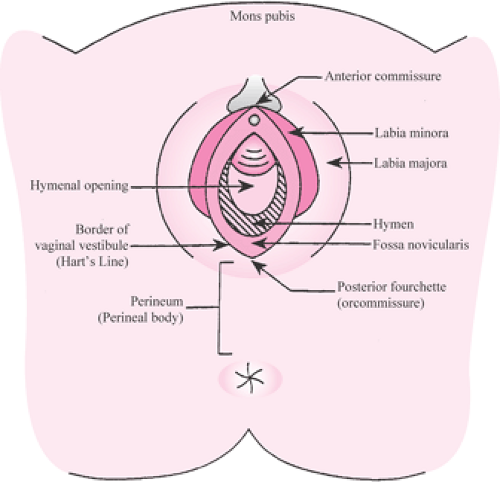

It is often helpful to examine a toddler on her mother’s lap while the mother elevates or abducts the child’s hips for the so-called “frog-leg position.” It is important to place the child on a towel or chuck pad in case urination occurs. An older child can sit straddling her mother’s lap fully clothed while the mother places the child’s legs in the stirrups. Usually, children between the ages of 4 and 6, and sometimes as young as 3, can position themselves in classic lithotomy with use of the stirrups. Clinicians can use their hands to provide lateral and downward traction on the area of the labia majora (Fig. 31.1). This will allow full visualization of the hymen and vaginal orifice.

Care should be taken to inform the child of the necessary steps of the exam. Continuously conversing with the child during the exam will allow her to relax. Children should never be forced or held down in order to perform a genital exam.

Vagina

Various positions have been described to visualize the vagina. In the very young infant or toddler, a Valsalva maneuver can be helpful in the exam; the child can be asked to pretend that she is blowing up a balloon or blowing out her birthday candles. This will often allow visualization of the distal 1 to 2 cm of the vagina. The knee–chest position is very helpful; children 3 years of age and older can typically cooperate and hold the knee–chest position. The child places her buttocks in the air with knees placed apart and allows her abdomen to sag. The examining physician and one assistant provide lateral and upward traction on the labia and buttocks. An otoscope can be used as a magnification instrument and light source to shine into the vagina, allowing visualization to the level of the cervix even without inserting the instrument. A vaginal speculum is neither appropriate nor indicated in the examination of the prepubertal child in the office (Fig. 31.2).

Uterus and Adnexa

Examination of the uterus and adnexa requires a rectal examination and should be reserved for the pediatric gynecology patient when information regarding the uterus or adnexa is necessary in the evaluation. Rectal bimanual examination should not be done routinely in every child requiring gynecologic examination.

In prepubertal children, the adnexa should not be palpable. In children, the ovaries lie at the level of the pelvic brim and drop into the pelvis with the onset of puberty. If an adnexa is palpable, there is, by definition, an adnexal enlargement that will require swift and careful evaluation of a possible ovarian neoplasm.

In the normal prepubertal child, the uterus should be easily palpable on rectal examination. Prior to puberty, two thirds of the uterine volume is cervical in contrast to the one third proportion in adults. The cervix, therefore, is a relatively easy structure to palpate on rectal examination in prepubertal children.

The Newborn

The obstetrician–gynecologist should be encouraged to observe the normal genitalia of the female infants that he or she delivers. Under the influence of maternal estrogens, the labia are generous in size, and the estrogenized hymen is prominent, turgid, and fimbriated or redundant in appearance. The female infant will sometimes experience an estrogen-withdrawal spotting episode within several days after birth. Parents should be informed of this normal phenomenon in an effort to preclude maternal anxiety and even unnecessary visits to the pediatric emergency department (ED). In a series of pediatric patients seen in the ED of Cleveland’s Children’s Hospital for vaginal bleeding, the vast majority of those under the age of 2 were seen for this reason. These ED visits are completely avoidable through parental education. Previously, before early obstetrical discharge, this estrogen-withdrawal spotting occurred in the hospital nursery.

Observation of the genitalia of female infants at birth allows the detection of various developmental and congenital abnormalities, some of which may be life threatening. If ambiguous genitalia are observed, the obstetrician must use excellent communication skills in the delivery room to help set the stage for the evaluation of the infant and to assist in decreasing parental anxiety. The parents should be informed that the baby’s genitals are not fully developed and a simple examination of the external genitalia cannot determine the actual sex. The parents should be told that they definitely have either a girl or a boy; but because development is not complete, data will have to be collected before they are told what sex the baby is and what treatment is required. Guesses must be avoided. It is critical to wait until all the information allows that the initial sex assignment given to the parents is the final and correct assignment.

The problem of ambiguous genitalia represents a social and potential medical emergency that is best handled by a team of specialists, which may include urologists, neonatologists, endocrinologists, and pediatric gynecologists. The differential diagnosis of ambiguous genitalia includes chromosomal abnormalities, enzyme deficiencies (such as 21-hydroxylase deficiency, which is a form of congenital adrenal hyperplasia [CAH]), and prenatal masculinization of a female fetus resulting from maternal androgen-secreting ovarian tumors or, rarely, drug exposures. The etiology of these problems as well as intersex disorders that may be discovered in an older child can be complex.

The possibility of CAH is especially critical to exclude. With the salt-wasting form of this disease, death can occur in the neonatal period, so electrolytes should be obtained immediately. Often overlooked is one simple physical exam finding that rules out CAH; the presence of gonads in the

labial scrotal folds in the infant with ambiguous genitalia eliminates the diagnosis.

labial scrotal folds in the infant with ambiguous genitalia eliminates the diagnosis.

One additional benefit of an observation of the genitalia of female infants at the time of birth is that some genital anomalies such as an imperforate hymen, vaginal agenesis, or other hymeneal anomalies may be diagnosed. Hymeneal abnormalities occur in <1% of newborn females and include imperforate hymens, cribriform hymens, and septate hymens. Normal hymeneal variations include hymeneal bumps, ridges, or bands. If there is any doubt about hymeneal patency, a rectal thermometer or small plastic catheter may be used to gently test for the vaginal space. Obstructive lesions include imperforate hymen, vaginal agenesis, or vaginal septa.

The timing of repair of an imperforate hymen remains controversial. Some experts recommend repair at puberty after full estrogenization. Others repair imperforate hymens after the neonatal interval when convenient for the family. This approach may avoid anxiety during the critical preadolescent years of psychosexual identity if the girl perceives there is something wrong with her genitalia that is awaiting repair. In some rare cases, a mucocolpos develops behind the imperforate hymen. This may be seen in the newborn, in which the mucus production is under the direction of maternal estrogens, or at the time of breast budding, in which endogenous estrogens orchestrate stimulation of mucus production. Very rarely, the mucocolpos may cause urinary obstruction that would necessitate urgent hymenectomy. Care must be taken to delineate the exact anatomic nature of the obstruction, and the clinician performing a hymenectomy should be comfortable that the obstruction is at the level of the hymen. Opening a thin imperforate hymen is a relatively easy surgical procedure, whereas the correction of other types of obstructive lesions such as vaginal septae requires careful planning, experience, and a high degree of skill.

Vulvovaginitis

Vulvovaginitis is the most common cause of vulvar symptoms in the prepubertal age group and the most common gynecologic complaint in prepubertal children. In children, the primary site of infection is often the vulva, in contrast to mature reproductive women in which the vagina is usually the primary site of infection. Vulvovaginitis in prepubertal children may be caused by specific pathogens, including Streptococcus pneumoniae, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia trachomatis, Shigella, Haemophilus influenzae, and pinworms. More commonly, however, the vulvovaginitis is nonspecific with no pathogenic organism responsible.

Cultures of the vagina in children with nonspecific vulvovaginitis will often reveal normal rectal flora such as Escherichia coli. Overgrowth of enteric bacteria can cause a primary vulvitis and a secondary vaginitis. In prepubertal children, the normal flora may invade and irritate the vulvar area. This invasion in prepubertal children is due to several circumstances. First, the labia minora are thin and unestrogenized. Second, there is no anatomic barrier between the vaginal orifice and the anus, since the labia majora are undeveloped and, prior to somatic growth, the anal and vaginal orifices are almost abutting one another. The unestrogenized vulva and vestibule normally appear mildly erythematous and may appear to be infected even when they are not, if examined by clinicians unaccustomed to routinely examining prepubertal children. Smegma around and beneath the prepuce resembles patches of candidal vulvitis to the inexperienced examiner. The prepubertal vagina is alkaline in contrast to the acidity of the mature reproductive woman’s vagina. At puberty, bacilli in the completely estrogenized vagina begin to produce larger amounts of lactic acid.

Presentation

It often is difficult for a young child to describe vulvar sensations such as pruritis, pain, or a burning sensation. She may only be able to communicate a discomfort. Parents sometimes note that the child cries during urination, scratches herself, touches herself frequently, or squirms when sitting in an effort to rub the sore vulva. Often, the child’s pediatrician will have evaluated the child for a urinary tract infection (UTI) and pinworms. Vulvovaginal complaints of any sort in a young child should prompt the consideration of possible sexual abuse.

Diagnosis

Most cases of vulvovaginitis are nonspecific, caused by normal intestinal flora. Specific pathogenic organisms must be excluded. When the initial presentation is compatible with nonspecific vulvovaginitis, some clinicians recommend proceeding with therapy based on the provisional diagnosis of nonspecific vulvovaginitis without performing diagnostic tests. In cases where treatment has been unsuccessful, it is important to perform diagnostic testing for specific pathogenic organisms. This may include cultures of the vagina to rule out S. pneumoniae, N. gonorrhoeae, C. trachomatis, Shigella, and H. influenzae. Both N. gonorrhoeae and C. trachomatis cause a vaginitis rather than cervicitis in children, so a vaginal culture is appropriate to exclude these pathogens. Use of DNA technology to diagnosis sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) in children currently is not recommended as a diagnostic strategy by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Use of indirect tests for STDs (such as enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay–based technology) is inappropriate in prepubertal children given the high possibility of false-positive results.

Several methods of obtaining vaginal cultures from the vagina of children are applicable. One such method is insertion into the vagina of a Dacron-tipped swab that is moistened with nonbacteriostatic saline. Avoiding touching the hymen helps to avoid any unnecessary discomfort to the child. Another method for obtaining cultures consists of

placement of a catheter through which nonbacteriostatic saline can be injected, aspirated, and sent for culture.

placement of a catheter through which nonbacteriostatic saline can be injected, aspirated, and sent for culture.

Therapy

The first step in treatment of nonspecific prepubertal vulvovaginitis involves attention to vulvar hygiene and toileting. Proper wiping will decrease rectal flora in the vulvovaginal areas. In addition, avoidance of vulvar irritants such as shampoo and deodorant soaps decreases the vulvar abrasion and irritation, making it more difficult for the rectal flora to invade the vulvar epithelium. Sitz baths are very helpful in relieving symptomatology. Scrubbing the vulvar area should be avoided, as this will only abrade the epithelium. Soaking the vulva clean is the preferable hygienic approach. A short course of broad-spectrum antibiotics can eliminate the overgrowth of enteric bacteria; however, unless the child changes her hygienic practices, the nonspecific vulvovaginitis is likely to recur when colonization recurs.

Fungal Infections

Fungal infections as a cause of vulvovaginitis are uncommon in prepubertal children. The prepubertal vagina is very alkaline and will not support fungal growth, which requires a more acidic environment. Exceptions to this rule may occur in immunosuppressed children such as organ recipients, children with HIV, or children receiving high-dose steroids. Diaper rash, which may present with erythema, excoriations, and satellite lesions primarily outside the vulvovaginal area, usually is fungal related.

Labial Agglutination

Labial agglutination is another common presenting complaint in prepubertal children between 3 months and 6 years of age. These are the years of a nadir in circulating estrogens. The abraded unestrogenized labia minora agglutinate and form a telltale line at the point of the agglutination that is visible on genital examination. These girls sometimes complain of genital discomfort and dripping of urine. Urine can be trapped in the “pouch” behind the agglutination. Despite the fact that the urethra may not be visible on genital examination, urinary obstruction typically is not a feature of this pediatric gynecologic problem.

Labial adhesions are extremely common and usually are symptomatic. Some small degree of adhesions is seen in many 3- to 4-year-old girls. Most experts agree that treatment should be reserved for symptomatic adhesions. The treatment consists of a short course of externally applied estrogen cream for several weeks. The area of agglutination will become thin and may spontaneously separate or can easily be separated in the office with the use of topical lidocaine jelly or anesthetic creams. It is critical that the estrogen be applied to the telltale line of adhesion and not lateral to the adhesion line. If pigmentation is seen lateral to the line of adhesion after estrogen application, this indicates improper application of the estrogen cream. Manual separation of thick adhesions should not be done in the office, as it is quite painful.

Attention must be given to the prevention of subsequent adhesions, as they clearly have a risk of recurring. One option is to recommend the use of a topical emollient, such as zinc oxide ointments (over-the-counter [OTC] “diaper rash” preventive creams) to prevent reagglutination in a tapering like manner after initial separation has occurred. Resolution of labial agglutination occurs at the onset of signs of endogenous estrogen production (breast budding).

Lichen Sclerosis et Atrophicus and Other Chronic Skin Conditions

Chronic skin conditions such as lichen sclerosis, seborrheic dermatitis, and atopic dermatitis may occur in young children. Lichen sclerosis et atrophicus (LSA) is a skin dystrophy usually seen in prepubertal girls or postmenopausal women. The appearance of LSA is consistent in both of these age groups: a “cigarette paper” type of appearance in a figure-of-eight distribution around the vulva and anus, ending at the labia majora. Breaks in the integument with small blood blisters and abrasion are common, with inexperienced clinicians misinterpreting the condition as trauma possibly secondary to sexual abuse. LSA is likely to occur in irritated vulvar areas in susceptible children. Appropriate first-line treatment in children is to prevent genital irritation and trauma. This may include avoidance of straddle activities, use of gel bike seats, and so forth. The extremely potent steroid (clobetasol) has been used in adults with success and is being used by experts in children despite a paucity of studies in this age group and the fact that clobetasol is not labeled for pediatric use. However, adrenal suppression from LSA treatment is extremely unlikely given the very small surface area where the potent steroid is applied. When this condition begins in childhood, it may regress with puberty, although this is not invariable. Some series suggest that it becomes less symptomatic during the reproductive years.

Vaginal Bleeding

Vaginal bleeding in a prepubertal child warrants a careful investigation. The differential diagnosis of vaginal bleeding hinges on the absence or presence of other signs of pubertal development. In young children with breast development, an evaluation for precocious puberty is warranted. Most children with genital bleeding will not have concomitant signs of pubertal development, and local causes of the bleeding are the most likely causes. The differential diagnosis in a child with genital bleeding without pubertal development is extensive and includes vulvar irritation/vulvovaginitis, foreign objects in the vagina, LSA, sexual abuse, trauma, Shigella vaginitis, breakdown of

labial adhesions, urethral prolapse, and malignant tumors of the vagina or cervix.

labial adhesions, urethral prolapse, and malignant tumors of the vagina or cervix.

Evaluation should include consideration of genital cultures, careful genital examination, and vaginal visualization. In cases where the vagina cannot be visualized in the office or bleeding continues despite a negative exam, an examination under anesthesia is indicated. The exam should rule out foreign objects and rare malignant vaginal tumors (sarcoma botryoides and endodermal vaginal sinus tumors) primarily seen in girls younger than 6 years of age.

Sexual Abuse

The possibility of sexual abuse should be considered in children presenting with a variety of presenting complaints including, but not limited to, vulvar vaginal symptoms, vaginal discharge, and genital bleeding. Sensitive but direct questioning of the parent or caretaker and the child by herself should be a part of any evaluation. The parent should be asked about any significant changes in behavior (such as the recent onset of nightmares, difficulties in school, changes in personality, etc.) that may accompany sexual abuse. Questioning the child who is verbal can be a useful “teachable moment” in which the physician explains the concept of the genital area as a “private zone” and the idea that touching in this area should be reported to a parent. One concrete way to explain the private-zone concept to a young child is to describe this as the areas that are covered by two-piece bathing suits. If the history is suspect or the injuries or physical findings are inconsistent with the reported history, a report must be made to the appropriate social service agency.

The possibility of sexual abuse must be assessed in children presenting with genital bleeding. However, it should be noted that the vast majority of children who have been sexually abused will have normal exams and not present with bleeding symptomatology. Hymeneal size is not an accurate way to determine if a child has been abused. The genital examination in abused children usually does not differ from the exam in non-abused children. The child’s history is of primary importance in the prosecution of sexual abuse. If forensic evidence is found, the source in the majority of cases is clothing and linens, which should always be collected in cases of recent assault.

Acute trauma and bleeding may result from a straddle injury or from sexual assault. Unintended trauma most commonly results in injury to the anterior vulva or laterally to the labia. Straddle injuries may result in the formation of a large vulvar hematoma, which may require evaluation. Penetrating injuries with transection of the hymen are quite rare in patients with straddle injuries. If a patient presents with a straddle injury and a hymeneal transection is present, significant consideration should be given to the possibility of sexual abuse. Any bleeding laceration of the vulva, and particularly hymeneal transactions, requires a careful examination to assure that there are no vaginal lacerations and to completely repair the injury. This may require an examination under anesthesia or the use of conscious sedation in the ED.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree