Palliative Care

Lauren Cobb

Teresa P. Díaz-Montes

DEFINITIONS

Palliative Care

Palliative care is specialized medical care for people with serious illnesses. The main focus is to provide patients with relief of distressing symptoms, pain, and the stress of a serious illness, irrespective of the prognosis. Additionally, it focuses on the psychological and spiritual care as well as the development of a support system for the patient and their family and aims to improve their quality of life. The palliative care team is composed of physicians, nurses, and other specialists who work together with the patient’s other physicians to provide an extra layer of support. It is appropriate at any age or at any stage in a serious illness and can be provided along with curative treatment. Benefits of palliative care are that it:

provides relief from pain, shortness of breath, nausea, and other distressing symptoms;

affirms life and regards dying as a normal process;

intends neither to hasten nor to postpone death;

integrates the psychological and spiritual aspects of patient care;

offers a support system to help patients live as actively as possible;

offers a support system to help the family cope;

uses a team approach to address the needs of patients and their families;

enhances quality of life;

is applicable early in the course of illness, in conjunction with other therapies that are intended to prolong life, such as chemotherapy or radiation therapy; and

can be obtained in the hospital setting (inpatient palliative care unit or consult service), in the outpatient setting, or in hospice.

Hospice Care (End-of-Life Care)

Hospice care is end-of-life care provided by health professionals and volunteers. The main goal is to provide medical, psychological, and spiritual support to the patient and their family. Additionally, the primary focus is to assist the dying individual in achieving peace, comfort, and dignity during the process. The caregivers try to control pain and other symptoms so the individual can remain as alert and comfortable as possible. Usually, a hospice patient is expected to live 6 months or less. Hospice care can take place at home, at a hospice center, in a hospital, or in a skilled nursing facility. It serves to:

deliver palliative care to patients at the end-of-life and

provide psychosocial care, nursing support, respite care, and bereavement support for the patient and their family.

To obtain Medicare hospice benefits:

Physician must certify that the patient has <6-month life expectancy assuming that the disease progresses as expected; there are no penalties for outliving the 6-month limit.

Patient must qualify for Medicare Part A (insurance for hospital care and skilled nursing facility care).

Patient selects a Medicare-approved hospice.

Patient elects hospice care over regular Medicare care. However, Medicare will still cover regular medical expenses when not associated with the terminal illness.

Physician Medicare benefits are maintained and patients can sign back on to Medicare whenever they wish.

In general, comfort and quality of life are the primary goals. A “do not resuscitate” order is not necessary.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

Do Not Resuscitate/Do Not Intubate

Do not resuscitate/do not intubate (DNR/DNI) is often a difficult discussion that patients expect their doctors to initiate. In general, the conversation should address the goals of treatment and the patient’s priorities, including prolongation of life and quality of life, preferences for life-sustaining therapies, and goals for pain management.

A patient can decide to be DNR/DNI but still pursue aggressive treatment; likewise, a patient can decide to pursue palliative treatment and still desire full resuscitation.

Data show that resuscitation and intubation efforts in oncology patients are rarely successful.

DNR/DNI discussion is urgently indicated if

death is imminent or the patient is otherwise at high risk for intubation or resuscitation (e.g., compromised pulmonary function);

the patient expresses a desire to die;

the patient or her family wants to discuss hospice options;

the patient has been recently hospitalized for progressing illness; or

the patient has significant suffering coupled with a poor prognosis.

Legal Considerations

The patient’s decision may not always be the same as that of her physician or family.

The principle of autonomy is an important consideration in American medicine.

Living wills and DNR orders can ensure that patients’ wishes are carried out.

Situations in which patients’ surrogate decision makers may disagree with previously formulated advance directives are common.

Legally and ethically, a surrogate decision maker must clearly follow the advance directive formulated by a competent patient.

Patients have the right to refuse or to withdraw care.

Permitting death by not intervening is distinct from the action of killing.

Physician-assisted suicide (i.e., a doctor provides a patient with the means to commit suicide with knowledge of the patient’s intent) is legal only in Oregon and Washington states.

Voluntary euthanasia (i.e., an intervention to end a patient’s life with her consent) is illegal in all states.

Difficulties can arise when patients and their families request treatments considered futile or inappropriate by their physicians.

No legal or societal consensus exists for situations in which patients and families disagree with physicians’ recommendations to stop treatment.

Consultation with an ethics committee or palliative care can be helpful.

Excellent communication regarding educational, spiritual, and psychosocial needs can often resolve these conflicts.

END-OF-LIFE CARE: PAIN MANAGEMENT

One of the most common and frightening symptoms for patients with terminal illness

Patient surveys have shown that pain associated with advanced illness is often undertreated and that approximately 40% of cancer pain is undertreated.

Pain should be addressed aggressively with multimodal therapy.

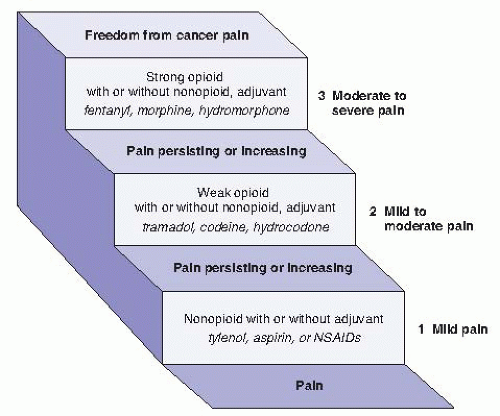

The World Health Organization (WHO) pain ladder provides guidelines for pain control escalation (Fig. 51-1).

Adjuvants include medicines, interventions, and alternative/complementary approaches designed to reduce fear or relieve anxiety.

Pain can be visceral, somatic, or neuropathic; many patients have multifactorial pain.

Medical Treatments

Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs

First step in the WHO pain treatment ladder

Can act synergistically with opioids

Should be given around the clock if pain is constant—twice daily options can aid in compliance

No nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) has greater efficacy than another.

Side effects include platelet inhibition (some nonsteroidals, such as Trilisate, do not inhibit platelets), gastrointestinal (GI) effects, and nephrotoxicity. These can be especially pronounced in older, frail patients.

Often contraindicated in clinical trials or while receiving chemotherapy. GI prophylaxis is usually indicated for long-term palliative use.

Acetaminophen is often just as effective and may be safer in some situations.

Opiates

Second and third steps in the WHO ladder

Opioids can be considered first line for terminal patients, especially those with severe pain.

When pain is constant, escalate to around-the-clock dosing or longer acting narcotics with rescue doses as needed.

There are various formulations and routes of administration (there is variation in response to these formulations and none are universally preferred over the other):

Mu opioid receptors are a subset of opioid receptors that provide anesthesia in response to specific narcotics. Pure mu agonists specifically target these receptors for pain relief: morphine, fentanyl, oxycodone, hydromorphone, and methadone.

Morphine: Available in oral tablets, solutions, elixirs, suppositories, and injectable formulas. Also available sublingually but is poorly absorbed in that route. Metabolized by the liver and excreted renally. Administer cautiously with renal insufficiency.

Fentanyl: Available in transdermal, transmucosal, and injectable formulations. No active metabolites, which make it useful in renal insufficiency. Relatively lower propensity to cause histamine release and itching.

Hydromorphone: Available in injectable and oral formulations and has a short half-life. Also useful in renal insufficiency, as its active metabolite is present in low concentration.

Oxycodone: In formulations alone or mixed with acetaminophen. Available in immediate- or extended-release formulas.

Methadone: Mu agonist but also N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist which helps to reverse opioid tolerance. Long half-life. Risk of prolonging QT interval.

Meperidine (Demerol) should be avoided, especially in renal failure, because its metabolite can accumulate and cause seizures.

Partial agonist/antagonists (nalbuphine or buprenorphine) should be avoided because they can precipitate withdrawal.

Refer to dosing guidelines (Table 51-1), as intravenous (IV) opioids are three times more potent than oral doses. Hydromorphone and fentanyl are much more potent than other opiates.

Severe Pain Crisis

Treat with a rapid taper of a fast-acting IV narcotic or with IV patient-controlled analgesia (PCA).

Once acute pain is controlled, calculate the dose and convert to a long-acting form.

Side Effects

To alleviate side effects, decrease the dose, change to a different narcotic, change the route, or treat the symptoms.

See the following text for treatment of nausea and vomiting.

Constipation is frequently a problem for patients on around-the-clock opioid. A bowel regimen should be prescribed; senna is often the first choice.

Sedation is common, although tolerance often develops.

Treat pruritus with Benadryl or low-dose nalbuphine or naloxone.

TABLE 51-1 Opioid Analgesics: Equivalent Dosing for Various Narcotic Formulations | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree