Evaluation of Amenorrhea

Irene Woo

Kyle J. Tobler

Amenorrhea is the absence of menses. It is physiologic during pregnancy, lactation, and menopause. The lack of regular, spontaneous menses for any other reason after the expected age of menarche is pathologic.

Primary amenorrhea: No menses by age 14 years in the absence of secondary sexual development or no menstruation by age 16 years with the presence of secondary sexual characteristics.

Secondary amenorrhea: The absence of menses in a previously menstruating woman. It is also defined as the lack of menses for 6 months or for three menstrual cycles in women that have experienced menarche. Evaluation, however, need not be deferred solely to conform to these definitions.

World Health Organization (WHO) amenorrhea groups

WHO group I (hypogonadotropic hypoestrogenic) has no endogenous estrogen production, normal or low follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) levels, normal prolactin (PRL) levels, and no lesion in the hypothalamus or pituitary.

WHO group II (normogonadotropic normoestrogenic) has endogenous estrogen production and normal levels of FSH and PRL.

WHO group III (hypergonadotropic hypoestrogenic) has elevated FSH levels and low to absent estrogen, indicative of premature ovarian failure (POF).

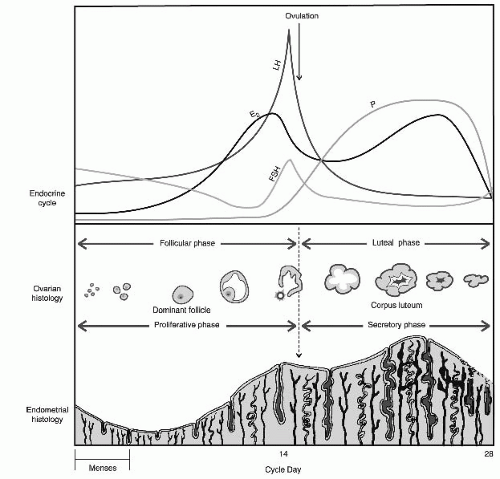

MENSTRUAL PHYSIOLOGY

Spontaneous, cyclic menstruation requires an intact and functional hypothalamicpituitary-ovarian axis (HPOA), endometrium, and genital outflow tract. Abnormalities in any of these structures may result in amenorrhea.

Normal Physiology of the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Ovarian Axis and Menstruation

Hypothalamus (arcuate nucleus) secretes gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) in pulses at specific frequencies and amplitudes into the portal circulation.

GnRH pulses stimulate gonadotrophs in the anterior pituitary to synthesize, store, and secrete gonadotropic hormones FSH and luteinizing hormone (LH) to the systemic circulation.

FSH stimulates ovarian follicle development and estradiol (E2) secretion.

E2 provides inhibitory feedback on the hypothalamus and pituitary, decreasing FSH release. E2 also stimulates proliferation of the endometrium.

Follicular growth continues until the threshold level of systemic E2 is surpassed, shifting to positive feedback, which triggers the LH surge.

LH surge causes the developing oocyte within the follicle to resume meiosis and ovulate.

Following ovulation, the follicle becomes a corpus luteum, rapidly shifting from primarily E2 production to progesterone production.

Progesterone decidualizes the endometrium in preparation for embryo implantation.

If pregnancy occurs, human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) secreted from the syncytiotrophoblast supports the corpus luteum and continued progesterone release.

If pregnancy does not occur, the corpus luteum will regress, ceasing to produce progesterone.

Progesterone withdrawal causes the endometrium to slough, resulting in the menstrual effluent.

The HPOA and endometrium demonstrate a finely orchestrated system that must be intact at all steps for a normal menstrual cycle to occur (Fig. 39-1).

EVALUATION OF AMENORRHEA

When to Evaluate for Amenorrhea

Rule out pregnancy, as both primary and secondary amenorrhea require an immediate evaluation for pregnancy.

Use clinical judgment. The aforementioned listed timeline defining amenorrhea does not need to be met prior to initiating an evaluation.

Do not overlook gross evidence of a disease process: Turner syndrome, frank virilization, obstructed vagina, or other evidences of a disease process.

Use a systematic approach, evaluating each critical component of menstruation: hypothalamus, pituitary, ovaries, uterus, and genital outflow tract.

Important History for Amenorrhea

Present illness: Presence of cyclic pelvic or abdominal pain, headache, visual changes, seizure, hot flushes, hot or cold temperature intolerance, vaginal dryness, urinary issues, hirsutism, virilization, galactorrhea, severe physical or emotional stress, changes in weight, diet, athletic training, or trauma

Past medical history: General health; chronic illnesses (especially autoimmune and thyroid disease); birth defects; all current and recently discontinued medications or supplements; contraception history (especially the use of depot medroxyprogesterone acetate); history of pelvic infection, complications with prior pregnancies or abortions, and any instrumentation of the uterus; and abdominal or pelvic surgeries. Most recent pregnancy and delivery and lactation history can be significant, as can a personal history of cancer treatment involving radiation therapy and/or chemotherapy.

Development: Age of thelarche, pubarche, and menarche, whether menarche was spontaneous or induced, and cycle regularity

Social: Severe physical or emotional stress, changes in weight or diet, and athletic training

Family history: History of late pubertal development, early menopause, mental retardation, or short stature

Important Physical Examination for Amenorrhea

Height, weight, body mass index, waist-to-hip ratio if obese, blood pressure, and pulse

General body habitus, looking for disease stigmata of Turner syndrome, Cushing syndrome, and thyroid disease. Also gross malnutrition or obesity.

Vision changes or peripheral loss of vision

Mouth and teeth for tooth enamel erosion

Skin evaluated for hyperpigmentation, acanthosis nigricans, abdominal striae, acne, hirsutism, and balding

Thyroid gland palpated for size, shape, and nodules

Breast development (Tanner stage), galactorrhea, or other breast discharge

Abdominal exam for masses, fat distribution, hirsutism, and aforementioned listed skin changes

External genitalia examined for hair distribution and virilization (clitoromegaly), imperforate hymen, or labial fusion

Internal genitalia examined for transverse vaginal septum, lateral vaginal obstruction, estrogenized vaginal mucosa, and the presence of a cervix with visible patent external cervical os

Rectal exam to evaluate the extent of hematocolpos and presence of uterus beyond a vaginal obstruction or absent vaginal orifice. Rectal exam can also assist in evaluating a patient with an intact hymen or infantile vaginal orifice.

Laboratory Evaluation of Amenorrhea

Important for laboratory evaluation to be guided by the aforementioned presenting history and physical examination

hCG to evaluate for pregnancy

FSH, E2, thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), and PRL

17-Hydroxyprogesterone, testosterone, and dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS) for patients with virilization, hirsutism, or androgen excess

Testosterone if concern for complete androgen insensitivity

Karyotype if concern for genitourinary abnormalities, suspicion for gonadal dysgenesis, or complete androgen insensitivity. Also consider if other nonrelated physical malformations are present.

Imaging Evaluation of Amenorrhea

Pelvic ultrasound for both primary and secondary amenorrhea

Hysterosalpingogram (HSG) or sonohysterography particularly for secondary amenorrhea and suspicion for Asherman syndrome

Follow-Up Laboratory and Imaging Studies for Initial Evaluation

Fragile X (FMR1) premutation for patients with POF

Antiadrenal antibodies and antithyroid antibodies (antiperoxidase and antithyroglobulin) for patients with POF

Karyotype for patients younger than 30 years with POF

Cortisol levels (24-hour urinary free cortisol, late-night salivary cortisol, dexamethasone suppression testing) for patients with suspected Cushing syndrome, also considered in patients evaluated for polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) and/or evidence of hyperandrogenism

Insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), free T4, and morning cortisol level for patients with a pituitary lesion identified by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

Adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) stimulation test for patients with elevated 17-hydroxyprogesterone

MRI of the pituitary for hyperprolactinemia or hypogonadotropic hypogonadism which has no other identifiable etiology (severe physical and emotional stress, malnutrition, medications, hypothyroidism)

MRI of pelvis. Obtain when genitourinary abnormalities are not well characterized or for surgical planning. Particularly useful when evaluating for imperforate hymen versus transverse vaginal septum, obstructed hemivagina, and noncommunicating or hypoplastic uterine horn.

Renal ultrasound and radiographs (computed tomography [CT] or x-ray) of spine for patients with müllerian dysgenesis

Endometrial biopsy (suspicion of genital tuberculosis or schistosomiasis)

Progesterone Withdrawal for Evaluation of Amenorrhea

Progestin challenge: 5 to 10 mg of medroxyprogesterone (Provera) for 5 to 7 days. Positive response is withdrawal bleed within 2 to 7 days after discontinuation of Provera.

Approximately 20% of patients with POF, hypothalamic amenorrhea, and hyperprolactinemia experience withdrawal flow depending on the degree of hypoestrogenism.

Failure to withdraw after sequential estrogen then estrogen/progestin is supportive of Asherman syndrome or cervical stenosis, but these conditions are rarely seen in the absence of a previous surgical procedure and the amenorrhea can be temporally related to the procedure.

Consider use of serum E2 level rather than use of progesterone withdrawal to determine status of estrogen.

Progesterone-induced withdrawal bleed is indicated as a treatment for amenorrhea and a thickened endometrium on ultrasound.

TABLE 39-1 Differential Diagnosis of Primary Amenorrhea | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||

Differential Diagnosis for Primary Amenorrhea

History and physical examination to evaluate for genital outflow obstruction

Keep pregnancy in differential, although less likely.

Keep the most common causes high on differential, (gonadal dysgenesis, müllerian anomalies/dysgenesis, and complete androgen insensitivity).

To develop a differential diagnosis, categorize the patients into four categories based on the presence or absence of a uterus and the presence or absence of breast development (indicative of estrogen) (Table 39-1).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree