Taddio A, Katz J: The effects of early pain experience in neonates on pain responses in infancy and childhood. Pediatr Drugs 2005;7:245–257 [PMID: 16118561].

PAIN ASSESSMENT

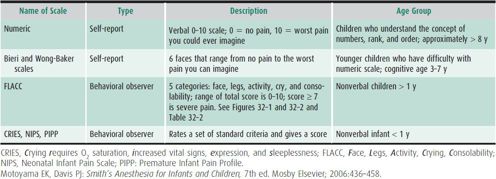

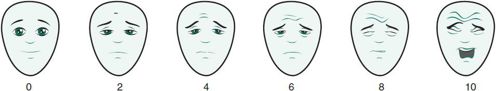

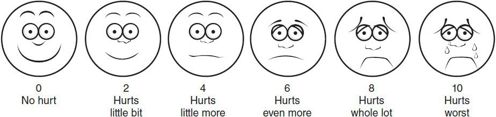

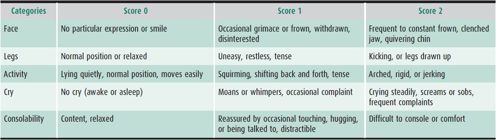

Standardizing pain measurements require the use of appropriate pain scales. At most institutions, pain scales are stratified by age (Table 32–1) and are used throughout the institution from operating room to medical floor to clinic, creating a common language around a patient’s pain. Pain assessment by scales has become the “5th vital sign” in hospital settings and is documented at least as frequently as heart rate and blood pressure at many pediatric centers around the world. There are many pain scales available, all of which have advantages and disadvantages (Figures 32–1 and 32–2, and Table 32–2, for examples). It is less important what type of scale is used, but that they are used on a consistent basis.

Table 32–1. Pain scales—description and age-appropriate use.

Figure 32–1. Bieri Faces Pain Scale, revised. (Reproduced with permission from Hicks CL, von Baeyer CL, Spafford P, et al: Faces Pain Scale-Revised: Toward a Common Metric in Pediatric Pain Measurement. PAIN 2001;Aug:93(2):173-183 [PMID: 2367140].)

Figure 32–1. Bieri Faces Pain Scale, revised. (Reproduced with permission from Hicks CL, von Baeyer CL, Spafford P, et al: Faces Pain Scale-Revised: Toward a Common Metric in Pediatric Pain Measurement. PAIN 2001;Aug:93(2):173-183 [PMID: 2367140].)

Figure 32–2. Wong-Baker Pain Scale. (Reproduced with permission from Hockenberry MJ, WilsonD: Wong’s essentials of pediatric nursing, ed 8, St. Louis, 2009, Mosby. Used with permission. Copyright Mosby [PMID: 11291631].)

Figure 32–2. Wong-Baker Pain Scale. (Reproduced with permission from Hockenberry MJ, WilsonD: Wong’s essentials of pediatric nursing, ed 8, St. Louis, 2009, Mosby. Used with permission. Copyright Mosby [PMID: 11291631].)

Table 32–2. FLACC pain assessment tool.

Special Populations

Noncommunicative patients such as neonates and the cognitively impaired are often difficult to assess for pain. For these patients using an appropriate assessment tool (see Table 32–1) on a frequent basis (every 1–2 hours) is essential in ensuring adequate pain control. For these populations, increasing pain score trends are often a sign of discomfort.

Bieri D et al: The Faces Pain Scale for the self-assessment of the severity of pain experienced by children: development, initial validation, and preliminary investigation for ratio scale properties. Pain 1990;41:139–150 [PMID: 2367140].

Merkel SI et al: The FLACC: a behavioral scale for scoring post-operative pain in young children. Pediatr Nurs 1997;23: 293–297 [PMID: 9220806].

Wong DL, Baker CM: Smiling faces as anchor for pain intensity scales. Pain 2001;89:295–300 [PMID: 11291631].

ACUTE PAIN

Definition Etiology

Definition Etiology

Acute pain is caused by an identifiable source. In most cases, it is self-limiting and treatment is a reflection of severity and type of injury. In children, the majority of acute pain is caused by trauma or, if in a hospital setting, an iatrogenic source such as surgery.

Treatment

Treatment

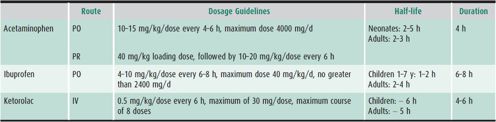

Treatment of acute pain is dependent on the disposition of the individual patient. For outpatient care the mainstay of treatment is nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (Table 32–3). Acetaminophen is the most commonly used NSAID. Acetaminophen is administered via the oral or rectal routes. Acetaminophen is more predictable in its effects as an oral dose. It has also been found that round-the-clock administration (oral 10–15 mg/kg, rectal 20 mg/kg) is better than PRN dosing for both minor pain or as an adjunct for major pain. The toxicity of acetaminophen is low in clinically used doses. However, the use of acetaminophen combined with many over-the-counter and prescription combination products has been a frequent cause of toxicity. Liver damage or failure can occur with doses exceeding 200 mg/kg/d. Other oral analgesics available in suspension are ibuprofen (10–15 mg/kg) and naproxen (10–20 mg/kg).

Table 32–3 Suggested doses for nonopioid analgesics.

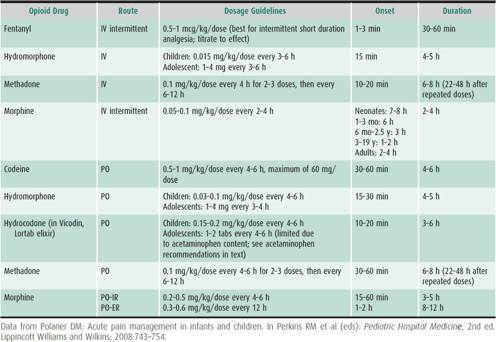

When pain is more severe, oral opioids can be added for short-term use (Table 32–4). Many of these opioids come formulated with an NSAID, that is, oxycodone/acetaminophen (Percocet) and hydrocodone/acetaminophen (Lortab). When using these combination drugs, the dose of drug is based on the opioid component. Other concomitantly administered similar NSAIDs should be discontinued. The most commonly used oral opioids are oxycodone, hydrocodone, and codeine. The use of codeine is least recommended due to its metabolism. Codeine is metabolized to morphine via the cytochrome P-450 2D4 isoenzyme. From 1% to 10% people (Asians 1%–2%, African Americans 1%–3%, Caucasians 5%–10%) are poor metabolizers as a result of a genetic polymorphism. Thus, patients with this defect get no effect from this drug. A very small percentage of patients (primarily from East Africa) are ultrarapid metabolizers. These patients convert 10–15 times the amount of parent drug to active compound which can result in clinical toxicity. Morphine, oxycodone, and hydrocodone are all available as suspensions, are active as administered, and are metabolized by multiple routes.

Table 32–4. Suggested doses of oral and intravenous opioids in infants and children.

For severe pain not amenable to oral analgesics, an intravenous opioid can be titrated to effect; options for pain relief are dependent on severity and location of pain and age. Intravenous opioids used as bolus dose, continuous infusion, and as part of a patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) infusion have a long track record of both safe and efficacious use in children. Often the NSAID ketorolac 0.5–1.0 mg/kg is used as an adjunct for severe pain. Side effects of ketorolac are the same as for adults: renal insufficiency, gastric irritability, and prolonged bleeding times due to decreased platelet adhesiveness. Patients with bleeding concerns should not receive ketorolac.

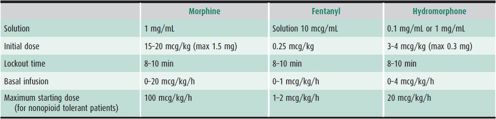

PCA pumps can be used in children as young as 6 years with proper instruction and coaching (Table 32–5). Morphine and hydromorphone are the most commonly used drugs for PCA management in the United States. Whenever PCA is used, it is imperative to assess patients frequently (at least hourly) to ensure adequate pain relief.

Table 32–5. PCA dosing recommendations.

Andersson T et al: Drug-metabolizing enzymes: evidence for clinical utility of pharmacogenomic tests. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2005;78:559–581 [PMID: 16338273].

Berde CB, Sethna N: Analgesics for the treatment of pain in children. N Engl J Med 2002 Oct 3;347(14):1094–1103 [PMID: 12362012].

CHRONIC PAIN MANAGEMENT

Assessment

Assessment

Chronic pain is a pain that persists past the usual course of an acute illness or beyond the time that is expected for an acute injury. In children this is an increasingly recognized problem. It is estimated that chronic pain may affect as much as 10%–15% of the population. The most common problems include headache, chronic abdominal pain, myofascial pain, fibromyalgia, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, complex regional pain syndrome, phantom limb pain, and pain associated with cancer. Chronic pain in children often has multiple other contributing factors, including psychological issues, psychosocial factors, sociologic factors, and family dynamics. Associating pain with a single physical cause can lead the physician to investigate the patient with repeated invasive testing, laboratory tests, and procedures and to overprescribe medications. A multidimensional assessment to chronic pain is optimal and often required.

McGrath PA, Ruskin, DA: Caring for children with chronic pain: ethical considerations. Paediatr Anaesth 2007 Jun;17(6): 505–508 [PMID: 17498011].

Weisman SJ, Rusy LM: Pain management in infants and children. In Motoyama EK, Davis PJ (eds): Smith’s Anesthesia for Infants and Children, 7th ed. Mosby Elsevier; 2006:436–458. www.ampainsoc.org/advocacy/pediatric.htm

Treatment

Treatment

When possible, a multidisciplinary team approach is standard of care for treating chronic pain in children. All children evaluated for chronic pain should be seen on their initial visit by all primary members of the team to establish a management strategy. Team members should include a pain physician, a pediatric psychologist and/or a psychiatrist, occupational and physical therapists (OT/PT), advanced pain nurses (APNs), and a social worker. The majority of pediatric chronic pain management programs in the United States base their approach on combined intensive rehabilitation and intensive psychotherapy relying minimally on invasive procedures and pharmacotherapy.

A. Tolerance, Dependence, and Addiction

Physiologic and psychological responses to opioids are similar between adults and children. A consensus paper by the American Academy of Pain Medicine, American Pain Society, and American Society of Addiction Medicine defined important differences between normal and pathologic responses to opioids. The definitions of tolerance dependence and addiction are listed below.

1. Tolerance—A state of adaptation in which exposure to a drug induces changes that result in a diminution of one or more of the drug’s effects over time. Tolerance develops at different rates for different opioid effects, that is, tolerance to sleepiness and respiratory depression occurs earlier than that to constipation and analgesia.

2. Dependence—A state of adaptation that is manifested by a drug class–specific withdrawal syndrome that can be produced by abrupt cessation, rapid dose reduction, decreasing blood level of the drug, and/or administration of an antagonist.

3. Addiction—A primary, chronic, neurobiologic disease, with genetic, psychosocial, and environmental factors influencing its development and manifestations. It is characterized by behaviors that include one or more of the following:

• Loss of Control over use of drug

• Craving and Compulsive use of drug

• Use despite adverse Consequences

Addiction is rare when opioids are used appropriately for acute pain on both inpatient and outpatient settings. It should be emphasized that tolerance and dependence do not equal addiction.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree