8.1 Orthopaedic problems

See Chapter 12.2 for Bone and joint infections.

Skeletal variations during growth

• intrauterine posture, sometimes described as ‘packaging’

• developmental variants – not present at birth, but may appear during growth and then disappear spontaneously. These include the common conditions of bow legs, knock knees, flat feet and in-toeing. These conditions seldom require active treatment but parents do need informed reassurance, which must be based on accurate knowledge of the natural history of these variations of posture in infants and children.

Intrauterine posture

Two common foot postures are seen in newborns.

Talipes calcaneovalgus

Many babies are born with the foot turned upwards at the ankle so that the toes lie close to the front of the shin: this is known as talipes calcaneovalgus (Fig. 8.1.1). This posture can be corrected passively so that the foot can be brought down to a plantigrade position or even into equinus. The condition has a strong tendency to correct itself spontaneously over a period of 2–3 months.

Bow legs

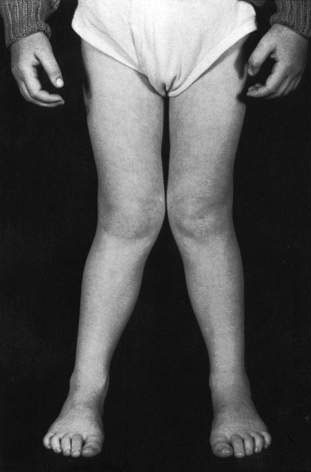

Bow legs (Fig. 8.1.2) are common up to 2 years of age; the parents will often be concerned that the legs are bowed and the feet turn in. The condition is not caused by bulky nappies, because the bowing is in the tibiae. It is a normal developmental process and does not require treatment apart from parental reassurance. If the bowing is in one leg only, you should investigate with plain X-rays to exclude pathological causes such as a bone dysplasia or growth abnormality.

Knock knees

A large proportion of the population between the ages of 2 and 7 years have knock knees (Fig. 8.1.3). This condition has a strong tendency to correct itself by the age of 7 years and as a rule the only management necessary is parental reassurance that improvement will occur. There is a rare form of knock knees (adolescent tibia vara) that presents in overweight children around the age of 12 years and which may require treatment by staple epiphysiodesis.

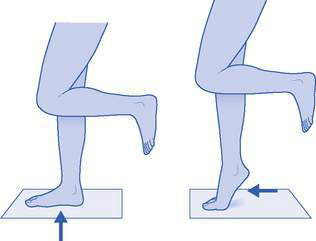

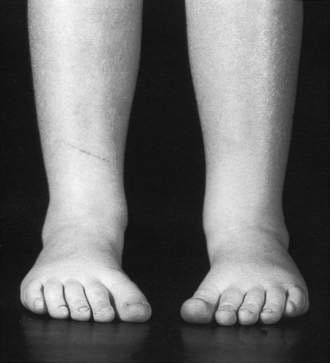

Rolling in of ankles

Parents will frequently mention this, especially after it has been noticed by a concerned grandparent or shoe-fitter. The rolling of the hind foot into valgus is due to physiological joint laxity and requires no treatment. The clinician can show the parents how the hind foot straightens when the child stands up on high tiptoes. This is the tiptoe test, which also demonstrates development of the medial longitudinal arch (Fig. 8.1.4). Orthotics for ‘rolling in’ are not required (see below).

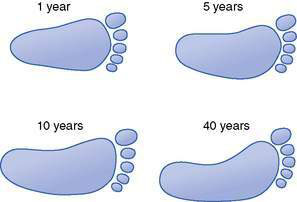

Flat feet

Flat feet in children are a frequent cause for parental concern. Usually this concern is unwarranted and the child’s foot is normal for age (Fig. 8.1.5). Often parents notice that their child’s foot appears flat. Sometimes the attendant fitter at the shoe shop may comment on the shape of the child’s foot. Children usually have low arches because they are loose-jointed and flexible. The arch flattens when they are standing. However, the arch can be better seen when the feet are hanging free or the child stands on tiptoes (the tiptoe test; see Fig. 8.1.4).

Curly middle toe

Sometimes the third toe curls inwards under the second toe so that the second toe tends to lie above the level of the first and third toes. Parents generally notice the abnormal posture of the second toe, but it is the third toe that is the cause of the problem. This can be safely ignored until the child is at least 2 years old. Occasionally a flexor tenotomy is required and provides excellent correction (Fig. 8.1.6).

In-toe gait (pigeon toeing)

Children with inset hips commonly sit between their feet with their hips in full internal rotation, the knees flexed and the legs splayed outwards (the ‘W’ position) (Fig. 8.1.7). This is the only way they can sit comfortably as they cannot externally rotate their hips sufficiently to sit in a cross-legged fashion. It is almost unknown for an adult to present with a complaint of in-toeing, which tells us that the natural history is spontaneous resolution.

Metatarsus adductus (Fig. 8.1.8) is a condition in which the feet are banana-shaped, with the convexity of the banana outwards and the toes directed towards each other. This may be due to intrauterine pressure; however, if it persists it is called metatarsus adductus. It is passively correctable and slowly rights itself, especially after walking commences. Very rarely, manipulation and plaster immobilization is necessary.