Oral Health Supervision

Ada M. Fenick and Linda P. Nelson

The condition of children’s teeth and the associated tissues are critical to their well-being. A child with poor dentition may be suffering with chronic pain and thus may have difficulties achieving proper nutrition. He or she may also be at risk of malocclusion and life-threatening infection. Further, dental problems such as early childhood caries can affect the secondary dentition if not addressed, with consequences extending through the life span. Caries are the most common dental problem encountered; the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey of 1999–2004 showed that 42% of children from ages 2 to 11 have some evidence of decay in their primary teeth, and 21% of children from ages 6 to 11 have evidence of decay in their secondary dentition.2 Unfortunately, a large proportion of these children have untreated caries.1 At higher risk of caries are children living in low-income and moderate-income households, children of color, and children with special health care needs.2,3 However, decay can and does occur in children of all backgrounds. As the health professional most likely to encounter new mothers and their infants at a young age, the pediatric clinician has a unique opportunity to provide anticipatory guidance that may help to prevent or slow the development of caries. Therefore, it behooves the provider to evaluate a child’s current dental status from an early age, to advise the child and the primary caregiver about positive and negative practices that may bear on future dentition, and to assist the family in establishing a dental home.

EVALUATION OF CURRENT DENTITION

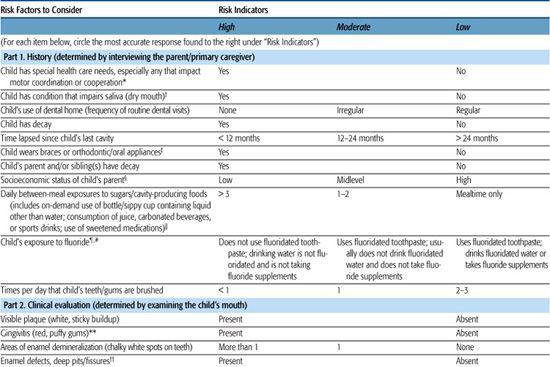

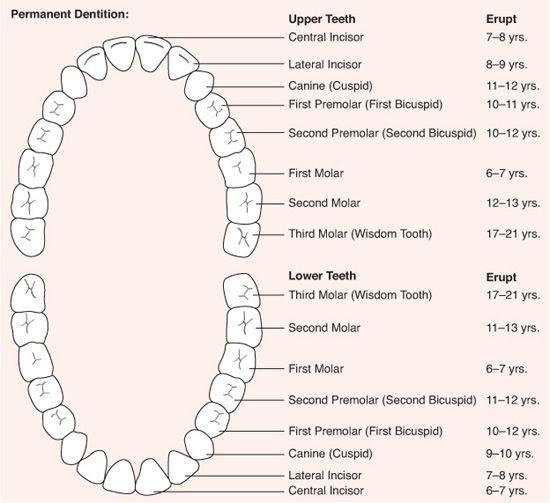

The evaluation of a child’s current dental status begins with age-appropriate history gathering regarding the child’s current practices. Data should be accumulated to assess risk for caries (see Table 13-1).4 Fixed events such as known decay, special health care needs, low socioeconomic status, and familial history of caries raise the child’s overall assessed risk for developing decay and should be noted in early life. However, mutable practices such as the use of a dental home, exposure to fluoride, exposure to simple sugars, and frequency of brushing are potentially modifiable by behavioral intervention and are critical to assess with every health supervision visit. In addition, sucking habits, including bottle, pacifier, and thumb, should be addressed to evaluate for the risk of malocclusion.

Once historical risk factors for poor dentition have been assessed, the pediatric provider should perform a physical screening as part of the general physical examination. The oral screening is different from a formal dental examination: The former is meant to assess for risk factors; the latter provides specific diagnoses.5 The screening should be conducted with the child feeling comfortable and safe, preferably on the lap of the primary caregiver at younger ages and with the primary caregiver close by for older children. Projection of a calm demeanor and use of distraction techniques will help to smooth the examination. With a gloved hand, the provider should palpate the outside of the mouth and then lift the lips away from the surface of the teeth to examine the teeth and gum line and to palpate the gum line. Using a tongue depressor, or a mirror if available, the provider can encourage the child to open his or her mouth in order to examine the facing surfaces of the molars, if any, and the inner surfaces of the teeth.

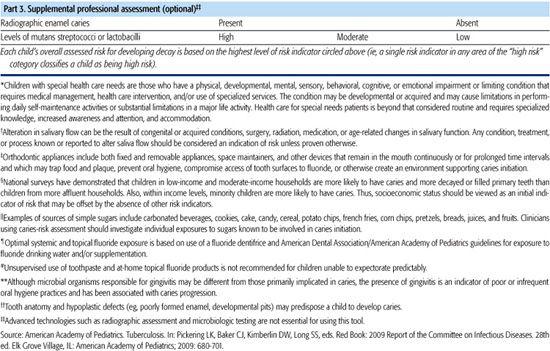

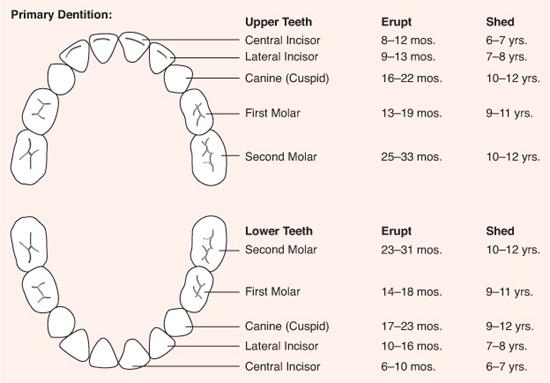

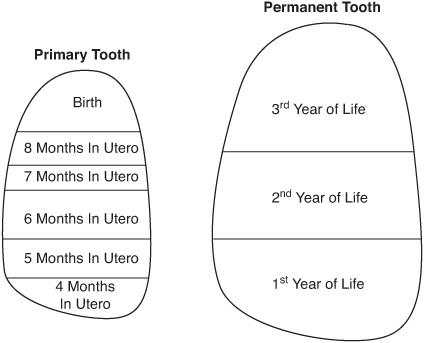

Teeth form, erupt, and exfoliate predictably (Fig. 13-1), and the provider should assess this timing. In addition, the provider should be alert for signs of caries, including both overt cavities and the demineralized (chalky white) areas that may form initially. The provider should be on alert for discolored, abnormally shaped, or traumatized teeth; plaque formation; and signs of current infection (such as dental abscess).5

As the enamel is forming, during late pregnancy and early infancy, it is very sensitive to systemic changes in the child, such as temperature changes or nutritional changes. Like the rings of a tree, the enamel records these changes that then become hypoplastic defects or hypocalcified areas within the enamel (Fig. 13-2). Enamel hypoplasia, a defect in the maturation process that results in voids in the enamel structure and predisposes the tooth to dental caries, is common in children with low birth weight or systemic illness in the neonatal period. There is considerable presumptive evidence that malnutrition or undernutrition during this period causes hypoplasia. A consistent association exists between clinical hypoplasia and early childhood caries.6

For further information, consult Chapters 374 to 380.

Table 13-1. AAPD Caries-Risk Assessment Tool (CAT)

FIGURE 13-1. Dental growth and development. (Reproduced from American Dental Association. Oral health topics, A–Z, tooth eruption charts. Available at: http://www.ada.org/public/topics/tooth_eruption.asp. Accessed January 29, 2008.)

ANTICIPATORY GUIDANCE

The provision of oral health anticipatory guidance is a partnership between the pediatrician, the dentist, and the family. The success of this partnership can be measured by good oral hygiene, fluoride exposure, sealants, and the resulting absence of dental caries, as well as trauma prevention in the use of a mouth guard during sports.

THE INFANT

THE INFANT

Every child should begin to receive oral health risk assessments by 6 months of age from a pediatrician or a qualified health professional. Infants identified as having significant risk of caries or assessed to be in one of the high-risk groups (children with special health care needs; children of mothers with high caries rate; children with demonstrable caries, plaque, demineralization, and/or staining; children who sleep with a bottle or breast-feed throughout the night; late-order offspring; children in families of low socioeconomic status) should be entered into an aggressive anticipatory guidance and intervention program provided by a dentist between 6 and 12 months.1

Infancy is perhaps the most important time to discuss risk factors that can be altered by behavior change, such as the vertical and horizontal transmission of Streptococcus mutans. Horizontal transmission is the transmission of bacteria among members of a group, such as among children at day care or between siblings. Vertical transmission, the transfer of bacteria via the saliva from the primary caregiver to the child, occurs when a mother tests the temperature of the bottle with their own mouth, tastes the food on a spoon and then feeds the child with the same utensil, or cleans the pacifier or bottle nipple with her mouth. The mother’s saliva has been shown to be the main reservoir from which infants acquire S. mutans. A mother with a high level of these bacteria continually recolonizes her infant when she employs such practices.

The timing of bacterial transmission is important, because acquisition of S. mutans before age 2 is a significant risk factor for development of early childhood caries and future dental caries.7 The success of the transmission and resultant colonization depends largely on the magnitude of the inoculum.8 During infancy, or better still, during late pregnancy, the mother and other intimate caregivers should be counseled to reduce their S. mutans count by having all their own dental caries restored and by setting up a routine to brush their own teeth twice a day with fluoridated toothpaste and to floss daily. To reduce the S. mutans inoculum, they may wish to rinse every night with an alcohol-free over-the-counter fluoride mouth rinse if they have more than 4 relatively recent fillings in their mouth or if they live in a nonfluoridated community.

Infancy is the optimal time for the family to examine their diet and eating practices. The family should eat foods containing sugar at mealtimes only, as limiting the frequency of consumption of fruit juices, candy, cookies, and cakes to mealtimes will decrease the risk of dental caries. Additionally, the family should be mindful of “sticky” foods that adhere to the teeth and thereby increase the risk of caries, such as dried fruit, rolled dry fruits, and sticky candy. If the carbohydrate sticks to the fingers and hand, it is likely to stick to the teeth and increase the risk of caries. Parents also should wean themselves off carbonated beverages. The pH of most of the soda products sold today is 3; below pH 5, S. mutans thrives.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree