Background

Severe maternal morbidity is increasing in the United States and has been estimated to occur in up to 1.3% of all deliveries. A standardized, multidisciplinary approach has been recommended to identify and review cases of severe maternal morbidity to identify opportunities for improvement in maternal care.

Objective

The aims of our study were to apply newly described gold standard guidelines to identify true severe maternal morbidity and to utilize a recently recommended multidisciplinary approach to determine the incidence of and characterize opportunities for improvement in care.

Study Design

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of all women admitted for delivery at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center from Jan. 1, 2012, through June 30, 2014. Electronic medical records were screened for severe maternal morbidity using the following criteria: International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision codes for severe illness identified by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; prolonged length of stay; intensive care unit admission; transfusion of ≥4 U of packed red blood cells; or hospital readmission within 30 days of discharge. A multidisciplinary team conducted in-depth review of each medical record that screened positive for severe maternal morbidity to determine if true severe maternal morbidity occurred. Each true case of severe maternal morbidity was presented to a multidisciplinary committee to determine a consensus opinion about the morbidity and if opportunities for improvement in care existed. Opportunity for improvement was described as strong, possible, or none. The incidence of opportunity for improvement was determined and categorized as system, provider, and/or patient. Morbidity was classified by primary cause, organ system, and underlying medical condition.

Results

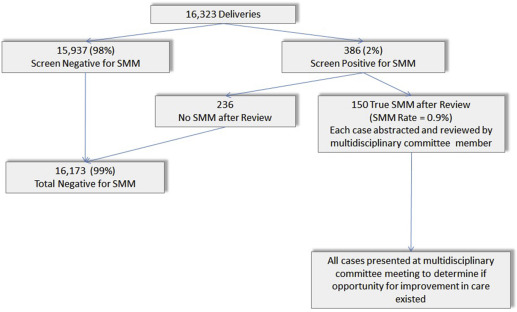

There were 16,323 deliveries of which 386 (2%) screened positive for severe maternal morbidity. Following review of each case, true severe maternal morbidity was present in 150 (0.9%) deliveries. We determined by multidisciplinary committee review that there was opportunity for improvement in care in 66 (44%) cases. The 2 most common underlying causes of severe maternal morbidity were hemorrhage (71.3%) and preeclampsia/eclampsia (10.7%). In cases with opportunity for improvement in care, provider factors were present in 78.8%, followed by patient (28.8%) and system (13.6%) factors.

Conclusion

We demonstrated the feasibility of a recently recommended review process of severe maternal morbidity at a large, academic medical center. We demonstrated that opportunity for improvement in care exists in 44% of cases and that the majority of these cases had contributing provider factors.

Introduction

Severe maternal morbidity (SMM) is estimated to occur in 0.5-1.3% of pregnancies in the United States. This accounts for at least 50,000 women per year and, similar to maternal mortality, the rate of SMM has been increasing. Because SMM lies within a continuum ranging from healthy pregnancy to death, efforts to identify preventable causes of SMM are thought to ultimately decrease SMM and, hence, maternal mortality. As such, a standardized, multidisciplinary committee approach for the identification and review of cases of SMM to identify opportunities for improvement in maternal care has been recommended. Although several methods for SMM screening have been used, recent reports have recommended using the following 2 screening criteria for SMM: pregnant or postpartum women who have been admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) and/or have received ≥4 U of packed red blood cells because of their high sensitivity and specificity for identification of cases of SMM. Identifying specific cases of SMM is challenging as the concept remains difficult to absolutely define and will always require clinical judgment. Recently, new gold standard clinical guidelines were described to define true cases of SMM that could be utilized to confirm cases of true SMM. These new, comprehensive guidelines specifically define SMM across multiple categories of morbidity. These screening and confirmatory tools have yet to be tested in clinical practice.

The aims of our study were to apply the newly described gold standard guidelines to identify true SMM cases and to utilize the recommended multidisciplinary committee approach to determine the incidence of and characterize opportunities for improvement in maternal care.

Materials and Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of all women admitted for delivery at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center from Jan. 1, 2012, through June 30, 2014, under an institutional review board–approved protocol (no. Pro00039046). Electronic medical records (EMR) were screened for SMM using the following criteria: International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision codes for severe illness as identified by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention ; prolonged length of stay (≥4 days for vaginal delivery, ≥6 days for cesarean delivery); ICU admission; transfusion of ≥4 U of packed red blood cells; or hospital readmission within 30 days of discharge. Each record that screened positive for SMM was reviewed in depth by 1 of the 3 primary authors (J.A.O., N.G., S.J.K.) to determine if true SMM was present utilizing the new gold standard clinical guidelines. For example, in the hemorrhage category, any woman who received ≥4 U of packed red blood cells met criteria for SMM. However, there were other clinical scenarios in the hemorrhage category that met criteria for SMM that did not require that 4 U of packed red blood cells were transfused. Specific examples included any woman who had a Bakri balloon placed and received 2 U of any blood product or any woman who underwent uterine artery embolization for hemorrhage regardless of the amount of blood products she received. The entire list of gold standard guidelines used as criteria for SMM for each category of morbidity has been published. Each case of true SMM was then assigned to, and reviewed in detail by, a member of our multidisciplinary committee who subsequently presented the case for review by the committee. The multidisciplinary committee was composed of a maternal-fetal medicine specialist, a maternal-fetal medicine fellow, a general obstetrician/gynecologist, a perinatal epidemiologist, an obstetric anesthesiologist, an obstetric anesthesiology fellow, and 2 labor and delivery registered nurses. The EMR of each case was abstracted utilizing a chart abstraction tool modified from the SMM abstraction and assessment form recommended by the Council on Patient Safety in Women’s Health Care ( www.safehealthcareforeverywoman.org/secure/smm-forms.php ). Committee members had the option to utilize the abstraction tool in either paper or electronic format. Information abstracted included broad demographic and specific obstetrical information relative to prenatal care and the course of clinical events relative to the severe morbidity during the admission. A narrative and time line of each case was created by the abstractor. A primary cause of morbidity was determined and the sequence of events leading to the morbidity was delineated. Categories of morbidity included: obstetrical hemorrhage (hemorrhage secondary to uterine atony, vaginal or cervical laceration), placental hemorrhage (hemorrhage secondary to placenta previa, placenta accreta, or placental abruption), preeclampsia/eclampsia, cardiovascular, sepsis/infection, pulmonary edema (pulmonary edema deemed SMM if required ≥2 doses of furosemide), and other. The multidisciplinary committee met weekly to present and review abstracted cases. During case presentation, the EMR was available for immediate review to address any questions regarding the course of events or clinical care. Any case that was originally determined to be SMM, but then determined at committee review to not meet criteria for SMM, was not included in final analysis.

Following presentation of each case, assessment of the case including confirmation of SMM, underlying etiology, sequence of events leading to morbidity, factors that contributed to morbidity, and opportunity to alter outcomes were determined by committee consensus. If there was disagreement among committee members, the EMR was reviewed with all committee members present until consensus regarding opportunities for improvement in care was reached. Factors that could have contributed to morbidity were divided into 3 groups (ie, system, provider, or patient) and each case could have none or ≥1. These factors have been defined in previous studies. The committee determined by consensus whether opportunities for improvement in care existed. If opportunity did exist, it was characterized as “strong” or “possible.” Once cases were presented and consensus regarding opportunity for improvement was reached, all data were entered into a database.

We used distribution-appropriate statistical tests of significance ( t tests for continuous and χ 2 tests for categorical/ordinal variables) to determine differences in SMM rates by sociodemographic and pregnancy characteristics. Further, we described the differences in opportunity for improvement in care by morbidity type. For cases of each morbidity type in which there was deemed to be an opportunity for improvement in care, we tabulated the frequencies of each of the 3 types of contributing factors (system, provider, and patient). We examined the potential for differences in the incidence of opportunity for improvement in care by various patient and pregnancy characteristics using unadjusted and multivariate logistic regression. All descriptive and statistical testing were performed using software (SAS, 9.3; SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

Materials and Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of all women admitted for delivery at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center from Jan. 1, 2012, through June 30, 2014, under an institutional review board–approved protocol (no. Pro00039046). Electronic medical records (EMR) were screened for SMM using the following criteria: International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision codes for severe illness as identified by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention ; prolonged length of stay (≥4 days for vaginal delivery, ≥6 days for cesarean delivery); ICU admission; transfusion of ≥4 U of packed red blood cells; or hospital readmission within 30 days of discharge. Each record that screened positive for SMM was reviewed in depth by 1 of the 3 primary authors (J.A.O., N.G., S.J.K.) to determine if true SMM was present utilizing the new gold standard clinical guidelines. For example, in the hemorrhage category, any woman who received ≥4 U of packed red blood cells met criteria for SMM. However, there were other clinical scenarios in the hemorrhage category that met criteria for SMM that did not require that 4 U of packed red blood cells were transfused. Specific examples included any woman who had a Bakri balloon placed and received 2 U of any blood product or any woman who underwent uterine artery embolization for hemorrhage regardless of the amount of blood products she received. The entire list of gold standard guidelines used as criteria for SMM for each category of morbidity has been published. Each case of true SMM was then assigned to, and reviewed in detail by, a member of our multidisciplinary committee who subsequently presented the case for review by the committee. The multidisciplinary committee was composed of a maternal-fetal medicine specialist, a maternal-fetal medicine fellow, a general obstetrician/gynecologist, a perinatal epidemiologist, an obstetric anesthesiologist, an obstetric anesthesiology fellow, and 2 labor and delivery registered nurses. The EMR of each case was abstracted utilizing a chart abstraction tool modified from the SMM abstraction and assessment form recommended by the Council on Patient Safety in Women’s Health Care ( www.safehealthcareforeverywoman.org/secure/smm-forms.php ). Committee members had the option to utilize the abstraction tool in either paper or electronic format. Information abstracted included broad demographic and specific obstetrical information relative to prenatal care and the course of clinical events relative to the severe morbidity during the admission. A narrative and time line of each case was created by the abstractor. A primary cause of morbidity was determined and the sequence of events leading to the morbidity was delineated. Categories of morbidity included: obstetrical hemorrhage (hemorrhage secondary to uterine atony, vaginal or cervical laceration), placental hemorrhage (hemorrhage secondary to placenta previa, placenta accreta, or placental abruption), preeclampsia/eclampsia, cardiovascular, sepsis/infection, pulmonary edema (pulmonary edema deemed SMM if required ≥2 doses of furosemide), and other. The multidisciplinary committee met weekly to present and review abstracted cases. During case presentation, the EMR was available for immediate review to address any questions regarding the course of events or clinical care. Any case that was originally determined to be SMM, but then determined at committee review to not meet criteria for SMM, was not included in final analysis.

Following presentation of each case, assessment of the case including confirmation of SMM, underlying etiology, sequence of events leading to morbidity, factors that contributed to morbidity, and opportunity to alter outcomes were determined by committee consensus. If there was disagreement among committee members, the EMR was reviewed with all committee members present until consensus regarding opportunities for improvement in care was reached. Factors that could have contributed to morbidity were divided into 3 groups (ie, system, provider, or patient) and each case could have none or ≥1. These factors have been defined in previous studies. The committee determined by consensus whether opportunities for improvement in care existed. If opportunity did exist, it was characterized as “strong” or “possible.” Once cases were presented and consensus regarding opportunity for improvement was reached, all data were entered into a database.

We used distribution-appropriate statistical tests of significance ( t tests for continuous and χ 2 tests for categorical/ordinal variables) to determine differences in SMM rates by sociodemographic and pregnancy characteristics. Further, we described the differences in opportunity for improvement in care by morbidity type. For cases of each morbidity type in which there was deemed to be an opportunity for improvement in care, we tabulated the frequencies of each of the 3 types of contributing factors (system, provider, and patient). We examined the potential for differences in the incidence of opportunity for improvement in care by various patient and pregnancy characteristics using unadjusted and multivariate logistic regression. All descriptive and statistical testing were performed using software (SAS, 9.3; SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

Results

There were 16,323 deliveries at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center from Jan. 1, 2012, through June 30, 2014, of which 386 (2%) screened positive for SMM and 150 (0.9%) were determined to be true cases of SMM ( Figure ). Demographics of the study population are presented in Table 1 . Women with SMM were significantly older than women without SMM ( P = .04). This difference was more pronounced in women who were ≥40 years old ( P = .008).