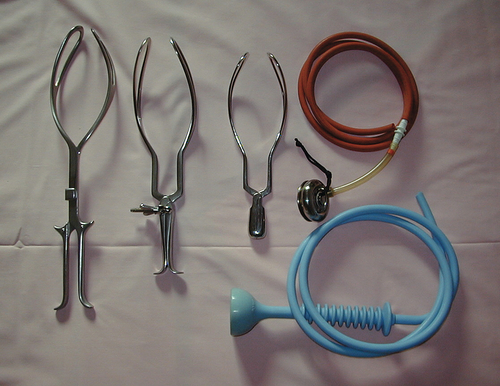

47 The phrase ‘operative delivery’ is used to describe both instrumental vaginal delivery and caesarean section. It may be indicated to expedite delivery in the presence of fetal distress, or for ‘delay’ or failed progress, despite good contractions and maternal effort. The choice between instrumental delivery and caesarean depends partly on the stage of labour, with instrumental delivery possible only in the second stage; even then, specific criteria must be met. Caesarean section can be used in both the first and second stages of labour and after a failed or abandoned attempt at instrumental delivery. The most common indications for instrumental delivery are presumed fetal distress (e.g. heart rate abnormalities, meconium, low pH on fetal blood sampling) and second-stage delay. The criteria in Box 47.1 must be fulfilled before the procedure can be carried out. A careful assessment is required prior to instrumental delivery, beginning with abdominal palpation. There should be no head palpable above the symphysis pubis although occasionally one-fifth is palpable in occipitoposterior positions. One of the most difficult parts of an instrumental delivery is being completely certain of the fetal head position prior to applying the forceps or ventouse (also known as vacuum-device). A systematic examination should determine the orientation of both the anterior and posterior fontanelles as the most common mistake is diagnosing an occipitoanterior position when in fact it is occipitoposterior. If there is a suspicion from palpation of the sutures that the fetal head is occipitotransverse, it is often helpful to try to feel for an ear anteriorly under the symphysis pubis. Some obstetricians use transabdominal ultrasound to confirm the position of the fetal head, others will seek a second opinion, or re-examine the patient in an operating theatre with good anaesthesia, where early recourse to caesarean section is possible. Incorrect assessment of the fetal head position or station results in a higher rate of failed instrumental delivery and morbidity for the mother and baby. Operative vaginal delivery requires a multidisciplinary approach to maximize the likelihood of success and minimize maternal and fetal trauma. In addition to the attending midwife, a practitioner experienced in neonatal resuscitation should be present and the anaesthetist is frequently involved in the provision of adequate analgesia. Umbilical artery and vein acid–base status should be routinely recorded immediately after delivery. The choice is between forceps and the ventouse. There are three main types of obstetric forceps (Fig. 47.1): Fig. 47.1Selected types of forceps and ventouse cups. The forceps, from left to right, are Kielland’s, Haig Ferguson’s and Wrigley’s. The orange tubing is attached to an O’Neill occipitoanterior metal cup, and the blue ventouse is a silastic cup. 1. Low-cavity outlet forceps (e.g. Wrigley’s, see History box), which are short and light and are used when the head is on the perineum 2. Mid-cavity forceps (e.g. Haig Ferguson’s, Neville-Barnes’, Simpson’s, see History boxes), for use when the sagittal suture is in the anteroposterior plane (usually occipitoanterior) 3. Kielland’s forceps (see History box) for rotational delivery to an occipitoanterior position. The reduced pelvic curve allows rotation about the axis of the handle.

Operative delivery

Introduction

Instrumental vaginal delivery

Forceps delivery

Low- or mid-cavity non-rotational forceps

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree