The goal of any treatment is to reduce pain and improve function of the knee. Surgical decisions are based on a number of factors including clinical symptoms; patient age; physeal maturity; and lesion stability, location, and size.17

Nonoperative Treatment

Currently, there is no role for treatment of an incidental juvenile OCD lesion. Most juvenile OCD lesions respond well to activity modification and limited weight bearing when stable. Nonoperative management consists of anti-inflammatory medications, relative rest, and protected weight bearing for 6 to 8 weeks. After this time, if the patient is symptom-free, a gradual return to sports and other high-impact activities takes place over another 6 to 8 weeks. Immobilization is controversial, as this can lead to stiffness and contradicts the initial work done by Salter et al.10,18 Immobilization for a period of greater than 16 weeks can lead to stiffness, cartilage degeneration, muscle atrophy, and poor healing10,19 and should be avoided. In a multicenter review by Hefti et al.,4 young patients treated nonoperatively had better results when they had lesions less than 2 cm2, had no signs of infection, and no effusion at the time of diagnosis. Classic location on the medial femoral condyle was also associated with higher healing rates,2 whereas larger lesions and those on the lateral femoral condyle had lower healing rates.20 Healing rates for skeletally immature patients with nonoperative treatment range from 50% to 94% at 10 to 18 months.21

Operative Treatment

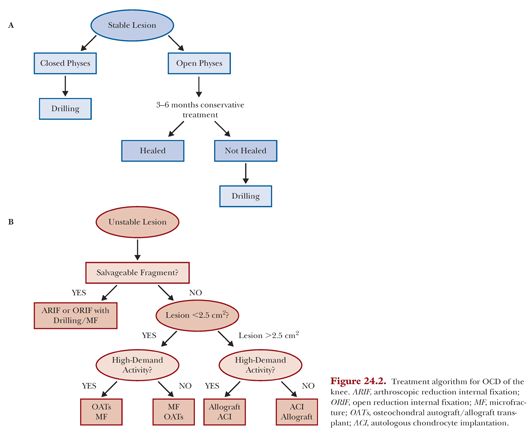

Surgical management of juvenile OCD lesions is indicated for patients with detached or unstable lesions or patients who fail a conservative course of treatment.2,10 There are a number of palliative, reparative, restorative, and reconstructive surgical procedures used to treat OCD lesions, depending on lesion characteristics and patient activity (Fig. 24.2). There is no consensus on which surgical procedure yields the best outcomes. A systematic review of surgical procedures for juvenile OCD lesions showed that radiographic and clinical improvements at short-, mid-, and long-term follow-up were lower for fragment excision than for drilling, microfracture, autologous chondrocyte implantation (ACI), osteochondral autograft/allograft, and fragment fixation.22 There was no difference in expected outcomes between the other procedures. Some authors conversely report success with fragment excision.15 The one option that remains the gold standard is repairing the native fragment in situ whenever possible. The reparative strategy of open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) technique with metal compression screw fixation is ideal if the fragment conformation allows and will be discussed here.

Open Reduction and Internal Fixation with Metal Compression Screws

Conceptually, unstable OCD lesions are biologically similar to a fracture nonunion, and to that extent, the same biomechanical principles apply related to enabling biology and adhering to the basic principles of osteosynthesis. As such, the goals of internal fixation of an unstable OCD lesion are to reapproximate the articular cartilage surfaces, promote vascular perfusion of the defect, and provide compressive force to aid in osseous integration, such that the fragment is effectively incorporated into the surrounding subchondral bone and articular cartilage.19,23

Patient Positioning and Setup

The patient should be positioned supine on the operating table, typically with the leg of the bed lowered and the thigh placed in a leg holder. This position allows for hyperflexion of the knee. However, if a patellar or trochlear lesion is present, open treatment is preferred and requires an arthrotomy. In this setting, the operating table can remain flat and no leg holder is needed. Diagnostic arthroscopy is always performed first to remove loose bodies and determine lesion stability, size, and ability to place a compression screw. Importantly, if the patient has evidence of an unstable lesion on imaging, the clinician must be appropriately aggressive with probing during arthroscopy, as symptomatic lesions may go untreated. Portals are placed in the typical anteromedial and anterolateral positions; however, a spinal needle can be used to establish an accessory portal used for fixation.

Defect Preparation

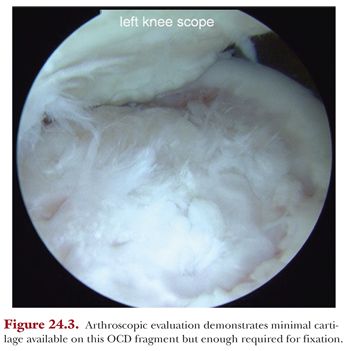

A probe or elevator can be used to elevate the fragment from its bed and assess for the quantity and quality of the bone on the backside of the fragment (Fig. 24.3). Ideally, a small hinge is left intact, keeping the fragment in the vicinity and preventing free rotation. Using an arthroscopic shaver, any remaining soft tissue at the interface is removed and débrided until bone is encountered. Bleeding can be stimulated from the lesion bed using microfracture awls, Kirschner wires (K-wire), or a drill. Turning off the inflow temporarily with mildly increased outflow should demonstrate egress of bone marrow elements. If unstable edges that will likely not remain viable are present, the combination of a basket and no. 11 blade scalpel is used to débride the edge of the defect.

Fragment Reduction and Fixation

Once the débridement of the defect site is complete, the fragment can be provisionally reduced with an arthroscopic probe. Occasionally, there are cystic changes or attritional bone loss that may benefit from local bone grafting. If required, an osteochondral autograft harvesting tube can be used to obtain small amounts of cancellous autograft from the intercondylar notch or lateral trochlear edge similar to obtaining a donor plug used in an osteochondral autograft/allograft transplant (OATs) procedure. The procedure can still be performed entirely arthroscopically or through a small arthrotomy if need be.

Typically, the surgeon should plan for the number of screws required for fixation, which is ideally a minimum of two to neutralize rotational forces. As the authors prefer the use of cannulated metal screws, placement of K-wires should be located where the screw will ultimately be placed. The K-wires are commonly placed through an accessory portal that is determined by initially triangulating with a spinal needle placed percutaneously to optimize a portal, allowing perpendicular access to the lesion surface. The authors prefer small-diameter, differentially pitched screws which have the following qualities: headless, cannulated, self-drilling, and variable pitch to allow for compression. First, one to two 0.045-in guide wires are placed into the lesion and defect. A depth gauge can be used to measure the length of the screw needed, which should be within 2 mm of the posterior cortex and typically 2 mm shorter than what is measured (allows for compression). Using a cannulated profile drill over the K-wire can aid in screw placement in young patients with dense bone. The screw is introduced with a manual screwdriver until the head is recessed within the cartilage surface, typically at least two turns. A second screw is placed when possible in a similar fashion. If using two or more screws, avoid parallel placement and err on the side of divergent placement to increase stability. Because the screws will likely be removed, it is helpful to use screw lengths of at least 24 to 26 mm when possible to facilitate screw removal.

Open Case

As mentioned, patellofemoral lesions (see Fig. 24.1) are often difficult to treat arthroscopically; therefore, the authors prefer the open approach. In this setting, the defect is first explored arthroscopically to ensure proper indications for fixation (see Fig. 24.3). This is then followed by a limited arthrotomy for trochlear lesions (Fig. 24.4) versus patellar eversion for patellar lesions (Fig. 24.5). The defect site is débrided and microfracture is performed, leading to a bleeding bed (Fig. 24.6). K-wires are then placed into the fragment for reduction (Fig. 24.7) followed by pilot drilling (Fig. 24.8) and screw placement (Fig. 24.9).