Nose and Sinus

Ellen S. Deutsch and Cecille G. Sulman

ANATOMY AND EMBRYOLOGY

The nose is the major portal of air exchange between the internal and external environment. Nasal functions include warming, lubricating, humidifying, filtering, stimulating, and regulating airflow. The roof of the nose also contains olfactory epithelium. In humans, the sense of smell contributes to the perception of taste, warns of impending hazards, and affects social interactions.

The nose is the preferred primary route of breathing. Many infants are obligate nose breathers and cannot compensate by oral breathing if their nose is obstructed. Occlusion of the nose in such an infant may cause serious airway difficulties. This characteristic generally persists from 6 weeks to 6 months of age.

THE NOSE

THE NOSE

The first sign of nasal development occurs at about 3 to 4 weeks of fetal life.1 It begins with nasal pits forming on the developing face that then invaginate to form the nasal sacs. The oronasal membrane separates the nasal sacs from the primitive oral cavity. The primitive nasal choanae communicate with the oral cavity when the membrane ruptures during the eighth week of gestation. As the membranous nasal cavities develop, neural crest cells migrate from the anterior skull base and proliferate in the facial processes to form the bony/cartilaginous skull base and nasal vaults, which are completely formed by the end of the 10th week.

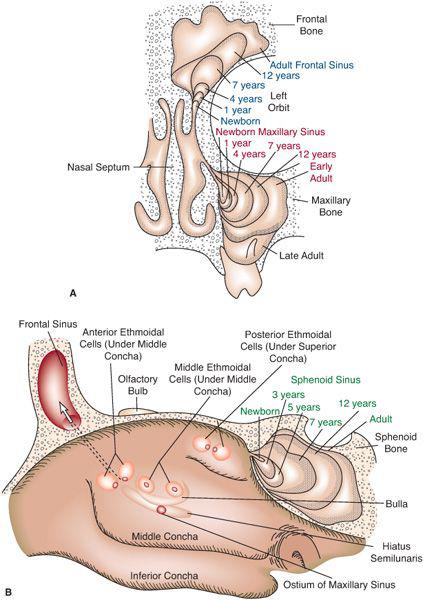

The upper third of the nose is supported by paired nasal bones and the frontal process of the maxilla. The middle third of the nose is supported by upper lateral cartilages attached to the undersurface of the nasal bones. The lower third of the nose is supported by lower lateral cartilages. Within the nose, paired inferior, middle, and superior turbinates arise primarily from the lateral nasal walls. The area of drainage below each turbinate is the respective meatus (Fig. 370-1). The turbinates are highly vascular structures that play a primary role in humidifying, warming, and filtering airflow. The nasal valve is the narrowest portion of the nasal passage located inside the anterior aspect of the nose. The valve helps control nasal airflow and affects the subjective sensation of the adequacy of nasal airflow. In neonates, as much as half of the total airway resistance occurs in the nose, and small amounts of additional obstruction can substantially affect airway patency.

The rich and complex vascularity of the nose is supplied by both internal and external carotid systems. In anterior portion of the septum, a confluence of vessels forms Kiesselbach plexus, the most common source of epistaxis. The veins in this region are valveless, which may facilitate spread of infection from the nasal cavity to the orbits and intracranial space.

THE SINUSES

THE SINUSES

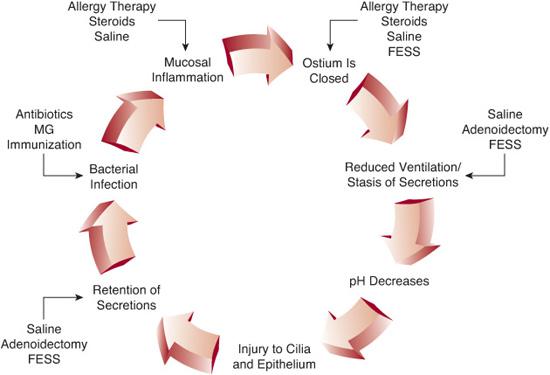

Development of the sinuses begins during fetal life but does not conclude until young adulthood (Fig. 370-1). Eventually, the sinuses are lined by respiratory mucosa composed of ciliated pseudostratified columnar epithelium interspersed by goblet cells. The maxillary sinus drains into the middle meatus under the middle turbinate in the region of the ostiomeatal unit. The ostiomeatal unit is not a discrete anatomic structure but refers collectively to several structures, including the draining routes and ostia of the maxillary, ethmoid, and frontal sinuses. Obstruction in this critical region of confluent drainage can lead to significant disease in the larger frontal and maxillary sinuses. The ethmoid sinuses start to develop during the third fetal month and have generally reached adult size by 12 years of age. The ethmoid bulla is one of the most constant and largest of the anterior ethmoid air cells. Large bullae may narrow sinus drainage outflow and impair mucociliary transport and ventilation. The sphenoid sinus can be identified during the fourth fetal month, and by the late teens, the sphenoid sinus development is nearly complete. There may be significant asymmetry between the two sphenoid sinuses because the intersinus septum tends to be bowed or twisted. The frontal sinus begins developing around 4 years of age and continues into the late teens. The size and symmetry of the adult frontal sinuses varies widely. Normally, the frontal sinus drains into the middle meatus.

The nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses are surrounded by many important structures, and disease in the paranasal sinuses may affect intraorbital and intracranial contents. The roof of the nasal cavity separates the nasal cavity from the brain. Housed within this region are the olfactory bulbs (Fig. 370-1B). Posterior to the sphenoid sinus is the sella turcica. Depending on the extent of aeration, the sphenoid sinus may be intimately related to the carotid arteries, optic nerves, pons, and cavernous sinus. The posterior wall of the frontal sinuses is composed of a thin layer of bone separating the frontal sinus from the anterior cranial fossa. The orbit is surrounded by the frontal, ethmoid, maxillary, and sphenoid sinuses. The posterior aspect of the nasal cavity communicates with the nasopharynx through large openings known as the choanae.

Figure 370-1. Internal nasal anatomy and sinus development. A: Coronal view representing the middle of the nose, demonstrating the developmental stages of the maxillary (lettered in red) and frontal (lettered in blue) sinuses. B: Sagittal view of the lateral nasal wall, demonstrating the ethmoid sinuses, the developmental stages of the sphenoid sinus (lettering in green), and the ostium of the maxillary sinus. Ethmoidal cells are a contiguous honeycomb, located lateral to the lateral wall of the nose with multiple ostium. The roof of the nasal cavity separates the nasal cavity from the brain. Housed within this region are the olfactory bulbs. (Source: Graney DO, Rice DH. Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 1998: 1060-1061.)

NASAL EXAMINATION

The infant and young child are best examined while sitting on the parent’s lap, with the parent securely holding the forehead and upper body. In the first portion of the exam, the overall external appearance is noted, including any craniofacial anomalies, masses, and resting mouth position. Incomplete closure of the mouth may be caused by nasal obstruction. Adenoid facies is a term used to describe the appearance of children with an open mouth posture; long, narrow face; high arched palate; dental malocclusion; short upper lip; and a “dull” affect. This appearance is nonspecific for chronic nasal obstruction, and adenoid hypertrophy may be only one of the causes. Nasal airflow can be assessed by holding a mirror under the nostril, which will fog from the humidity of warm airflow. Voice quality may also signal nasal obstruction. Nasal obstruction with too little air escaping through the nose results in hyponasal speech. This is in contrast to hypernasal speech, which results from air inappropriately escaping through the nose when vowels or consonants such as “s,” “b,” and “k” are spoken. Hypernasal speech, or velopharyngeal insufficiency, may occur in patients with cleft palate, velo-cardio-facial syndrome (22q deletion), or other causes of inadequate closure of the soft palate

A nasal speculum or a large ear speculum on an otoscope may be used to examine the inside of the nose. This is generally well tolerated by children and allows assessment of the anterior septum, floor of the nose, inferior turbinates, and mucosa. The septum is visualized for deviation or other abnormalities. The inferior turbinates appear as balls of tissue originating from the lateral wall near the floor of the nose. These may be mistaken for polyps if they are significantly edematous. Visualization more superiorly and posteriorly often provides a view of the middle turbinate and the middle meatus, the “tear-shaped” space (narrow at the superior end) between the middle and inferior turbinate. Hypertrophy of one inferior turbinate may be a result of the normal nasal cycle of alternating engorgement, but simultaneous bilateral hypertrophy may have other causes. Engorgement of the turbinates as a result of inflammation or other causes may result in nasal obstruction. “Cyanotic” or pale, bluish turbinates are classically attributed to allergies, but may occur in association with any cause of decreased nasal airflow. Mucosa quality as well as the presence of secretions may indicate an inflammatory process causing nasal obstruction. If a more thorough evaluation of the nasal cavity and nasopharynx is desired, nasal endoscopy with a flexible nasopharyngoscope can be performed by an otolaryngologist in children of all ages.

CONGENITAL NASAL ANOMALIES

Nasal obstruction in neonates not only causes difficulty breathing but also results in feeding difficulties, aspiration, and sleep problems. Complete nasal obstruction may be life threatening if not addressed in a timely fashion. A large number of congenital and/or genetic anomalies include nasal deformities or malformations, including arhinia, or complete absence of the nose. There may be an associated central nervous system abnormality, such as holoprosencephaly, or these patients may possess normal intelligence.2 Patients with polyrrhinia, or “double nose,” often have bilateral choanal atresia. It is hypothesized that the usual development of the frontonasal process is altered with duplication of the medial nasal processes and septal elements. Patients presenting with these anomalies require a comprehensive approach to both diagnosis and management as discussed in Chapter 177. The more commonly observed congenital nasal anomalies are discussed below.

CHOANAL ATRESIA

CHOANAL ATRESIA

Choanal atresia is the most common congenital nasal abnormality, occurring in 1 of every 5000 to 8000 births.3 Choanal atresia may be unilateral or bilateral. Infants born with complete bilateral choanal atresia present with respiratory distress. Acute management includes opening the mouth using an oral airway. Gavage feedings may be necessary due to feeding difficulties since the infant is unable to coordinate breathing, sucking, and swallowing without an adequate nasal airway. Some infants will require intubation until the atresia is surgically repaired. Unilateral choanal atresia is twice as common as bilateral choanal atresia, but symptoms are less obvious; therefore, diagnosis may be delayed. Traditionally, an attempt is made to pass an 8 French catheter through both nasal cavities at birth; passage of the catheter rules out complete choanal atresia but does not guarantee adequate nasal airflow. Nasal obstruction warrants further evaluation, including endoscopy, and in cases of complete obstruction, a computed tomography (CT) scan. Patients with choanal atresia should also be evaluated for concomitant abnormalities. CHARGE association (coloboma, heart disease, atresia choanae, retarded development of the nervous system, genital hypoplasia, and ear anomalies or deafness) occurs in a significant percentage of infants with choanal atresia. Bilateral choanal atresia requires prompt repair, whereas unilateral atresia can generally be delayed until the child is 1 to 2 years of age.

OTHER CAUSES OF CONGENITAL NASAL OBSTRUCTION

OTHER CAUSES OF CONGENITAL NASAL OBSTRUCTION

Dacrocystoceles

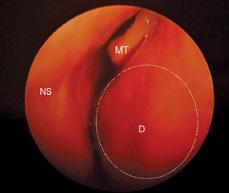

Dacryocystoceles also cause nasal obstruction in the infant. A dacryocystocele occurs when there is occlusion of the lacrimal duct resulting in a triad of a cystic medial canthal mass, dilatation of the nasolacrimal duct, and a submucosal nasal cavity mass in the inferior meatus (Fig. 370-2). Approximately 30% of full-term infants are born with nasolacrimal duct obstruction; this resolves spontaneously in 85% by about 9 months of age.4 If obstruction impairs breathing or feeding, treatment options include endoscopic marsupialization, nasolacrimal duct probing, and stent placement.

Nasal Obstruction without Choanal Atresia (NOWCA)

This term provides a reminder to consider a variety of causes of nasal obstruction in infants in addition to choanal atresia. Symptoms include respiratory distress, rhinorrhea, feeding difficulties, and sleep disturbances. Structural causes such as nasopharyngeal masses, choanal stenosis, or pyriform aperture stenosis (narrowed anterior bony nasal opening), as well as inflammatory causes such as edema or infection, should be sought and treated as indicated. When NOWCA is managed expectantly, weight gain should be monitored because significant obstruction can interfere with growth.

CONGENITAL NASAL MASSES

CONGENITAL NASAL MASSES

Congenital midline nasal masses are rare and occur in about 1 in 30,000 live births in the United States,1,4 but are important because of their potential for intracranial connections. Congenital nasal masses can be divided into three major groups according to their tissues of origin. Neurogenic tumors are often mid-line, including gliomas, encephaloceles, and neurofibromas. Dermoid cysts are also often midline; they originate from ectodermal and mesodermal tissue. Hemangiomas, vascular lesions arising from mesoderm, are more variable in their location.

Encephaloceles and Gliomas

Encephaloceles and gliomas are thought to arise from the same embryonic defect: faulty closure of the foramen cecum at approximately the third week of fetal development. Herniation of cranial contents through a skull defect is known as an encephalocele. A meningocele includes meninges only; a meningoencephalocele includes both brain and meninges. Patients may have a widened nose, hypertelorism, or other midline central nervous system anomalies. Encephaloceles tend to enlarge with crying (Furstenberg test) and are bluish, soft, compressible masses that transilluminate. The incidence of encephaloceles is three times greater in males. They often occur as a component of syndromes such as Apert syndrome or in association with other anomalies such as ocular or frontonasal dysplasia.2 A glioma is an encephalocele that has lost the intracranial connection, although 15% remain attached to the central nervous system by a fibrous stalk. Gliomas do not transilluminate and are typically reddish, firm, and noncompressible. Diagnosis of encephaloceles and glioma is confirmed with nasal endoscopy and CT scan to delineate bony structures and MRI to identify any intracranial connections. If there is an intracranial connection associated with any of the defects, neurosurgical consultation should be obtained. Otherwise, treatment is by excision.

Figure 370-2. Dacryocystocele in left nares. D, dacryocystocele; MT, middle turbinate; NS, nasal septum.

Dermoids

Dermoids are the most common midline nasal mass.4 Dermoids may present externally as a firm, lobulated, and noncompressible mass with a negative Furstenberg test; they do not transilluminate. The most frequent presentation is a slow-growing cystic mass over the dorsum of the nose, located anywhere along the midline or near-midline from the nasal tip to the glabella. They often originate at a pit, which may have hair, cheesy material, or drainage protruding from the sinus opening. Dermoids may become locally infected and present as an abscess. Slow expansion can result in destruction of the nasal bones or widening of the nasal bridge. Dermoids are believed to be of similar embryologic origin to encephaloceles and gliomas. During development, a portion of the dura develops in close association with the skin of the nose. This normally separates and is retracted up through the foramen cecum, which then closes. Dura that remains in contact with skin as it retracts will result in a sinus or pit. Most dermoid cysts occur sporadically, although rare familial associations have been reported. Possible connection with the central nervous system via a cranial defect should be evaluated by MRI and/or CT scan. Complete excision must be performed to prevent recurrence.2

Teratomas

Teratomas generally originate in the nasopharynx rather than the nose or sinuses, but they can cause nasal obstruction. Teratomas range in complexity from dermoids to epignathi. “Hairy polyps” are a type of dermoid presenting as a fleshy mass comprising disorganized ectoderm and mesoderm. These pedunculated masses originate in the nasopharynx and may protrude beyond the margin of the soft palate; wide excision of the pedicle is usually curative. True epignathi, containing well-developed recognizable fetal parts, are rarely malignant. Depending on their size and location, nasopharyngeal teratomas may interfere with breathing and eating.

NASAL OBSTRUCTION, INFLAMMATION, AND RHINORRHEA

The differential diagnosis for nasal obstruction, inflammation, or rhinorrhea is diverse and challenging. The most common cause of nasal obstruction and rhinorrhea in young children is a viral upper respiratory tract infection. Young children experience an average of six to eight “colds” per year; many are viral and can be treated expectantly. Conservative measures include the use of hypertonic saline to rinse secretions. Various causes of allergic and nonallergic rhinitis, which may also contribute to nasal obstruction, are discussed in Chapter 192.

Infectious Causes

Infections of the nasal skin are uncommon and are often related to skin blemishes or to hair follicles at the anterior choanae. Digital trauma, either “nose picking” or attempts to express the contents of a pustule, may result in folliculitis, vestibulitis, or cellulitis and abscess. Staphylococcus aureus is the most common pathogen. Treatment consists of systemic antibiotics and topical application of antibiotic ointment. Development of increasing erythema, cellulitis, or an abscess of the nose or midface should be treated aggressively because of the potential for the infection to spread to the cavernous sinus via the valveless nasal veins.

Adenoid Hypertrophy and Adenoiditis

Adenoids are located just posterior to the back of the nose. Because of their location, they are difficult to examine. Nevertheless, adenoid hypertrophy or chronic adenoiditis may contribute to sinonasal disease. Adenoids consist of lymphoid tissue and are present early in life, with growth continuing until about 4 to 10 years of age. Adenoid hypertrophy can be evaluated with a lateral neck radiograph or by endoscopy, whereas chronic adenoiditis is diagnosed based on symptoms and may occur without adenoid enlargement. Nasal obstruction, mouth breathing, and persistent nasal congestion or discharge in the child who “always seems to have a cold” may indicate chronic adenoiditis. Adenoidectomy is indicated for chronic adenoiditis, adenoid hypertrophy with upper airway obstruction, and, selectively, for chronic middle ear disease and chronic sinusitis.5

Nasal Foreign Bodies

Children often place foreign bodies in their noses without parental knowledge, resulting in delayed diagnosis associated with characteristic foul odor and unilateral rhinorrhea. Foreign body lodgment should be considered if a child has persistent unilateral rhinorrhea unresponsive to routine management. With appropriate preparation and equipment, many intranasal foreign bodies can be removed in an office setting; occasionally, difficult cases may require removal under general anesthesia.

Button batteries are a special case; they are very hazardous and should be managed promptly.6 Local damage may occur within the first hour after placement into a body cavity, and nasal septal perforation has been reported within 7 hours of button battery lodgment.6 In the esophagus, burns have occurred as early as 4 hours and perforation as early as 6 hours after button battery ingestion.7 Three mechanisms contribute to extensive damage to surrounding mucosa: (1) moisture in the nasal cavity corrodes the battery casing, releasing alkaline contents; (2) the batteries, bathed in electrolyte-rich nasal secretions, can generate local currents; and (3) local pressure. Septal perforations may contribute to saddle-nose deformity as well as nasal crusting, foul smell, and epistaxis; surgical repair is technically challenging. Unfortunately, these injuries have become more common, as button batteries have become ubiquitous in toys, clothing, and greeting cards; many of which are intended for use by children and are not labeled as to their potential hazard.

NASAL MASSES

In addition to the congenital masses noted previously, benign and malignant neoplasms may present as nasal masses (see also Chapter 373).

Nasal Polyps

Nasal polyps are rare before adolescence, except for in children with cystic fibrosis (CF). Evaluation of a young child with nasal polyps should include consideration of CF or an encephalocele. The role of allergy in causing nasal polyps is controversial and probably limited. Polyps are most commonly visualized emanating from the middle meatus; they often have a gelatinous appearance (eFig. 370.1  ). Antrochoanal polyps are a distinct type of polyp arising from the maxillary sinus and entering the nose via the middle meatus. They expand posteriorly into the nasopharynx and can cause significant nasal airway obstruction.

). Antrochoanal polyps are a distinct type of polyp arising from the maxillary sinus and entering the nose via the middle meatus. They expand posteriorly into the nasopharynx and can cause significant nasal airway obstruction.

Inverting papilloma and allergic fungal sinusitis are uncommon causes of nasal polyps but should be considered, especially if the polyps are unilateral and bone expansion or erosion is demonstrated on imaging studies. Inverting papillomas may have the appearance of polyps and similarly appear to arise from the region of the lateral nasal wall but are locally destructive. Surgical excision is the main therapeutic modality; there is a high rate of recurrence, and infrequently, they may become malignant.

Angiofibromas

Juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibromas (JNA) are aggressive, poorly encapsulated, highly vascular but histologically benign tumors that originate in the nasopharynx in pubertal and prepubertal male adolescents. The classic symptoms include nasal obstruction and epistaxis, facial edema, proptosis, ipsilateral otitis media. Hearing loss and neurologic changes may also be present. Because of their vascularity, biopsy may be associated with significant hemorrhage, and radiologic studies combined with the clinical history are generally adequate to confirm the diagnosis (eFig. 370.2  ). Management options usually include radiotherapy or excision via open and/or endoscopic approaches8; embolization of major feeding vessels is accomplished just prior to resection.

). Management options usually include radiotherapy or excision via open and/or endoscopic approaches8; embolization of major feeding vessels is accomplished just prior to resection.

Other Nasal Masses

Uncommon benign sinonasal masses include massive enlargement of a concha bullosa (an aerated cell within the middle turbinate), mucocele, peripheral-nerve-sheath tumors such as schwannomas, squamous cell papillomas, giant cell tumors, pygenic granulomas, and diseases of dental origin. Fibroosseous lesions may present with facial deformity, nasal obstruction, proptosis, epistaxis, and decreased vision. Fibrous dysplasia, ossifying fibroma, and juvenile (aggressive) ossifying fibroma replace normal bone with fibrous tissue.

Malignant sinonasal tumors are rare in children, but lymphomas and sarcomas can occur as early as infancy. Carcinomas and neural malignancies may also occur in children. Rhabdomyosarcomas and fibrosarcomas are the most common soft tissue sarcomas arising within the sinonasal region; osteosarcomas and chondrosarcomas may also occur (eFig. 370.3  ). Non-Hodgkin lymphoma may originate in the sinuses. Primitive neuroectodermal tumor (PNET) is a soft tissue neoplasm that can occur in newborns up to young adults. Many, but not all, sinonasal malignancies have a rapid course and may present with symptoms such as nasal obstruction, rhinorrhea, epistaxis, epiphora, proptosis, photophobia, visual loss, lymphadenopathy, facial paresthesia, or other cranial nerve involvement, as well as acute systemic symptoms such as fatigue, fever, weight loss, bone pain, or abdominal pain.

). Non-Hodgkin lymphoma may originate in the sinuses. Primitive neuroectodermal tumor (PNET) is a soft tissue neoplasm that can occur in newborns up to young adults. Many, but not all, sinonasal malignancies have a rapid course and may present with symptoms such as nasal obstruction, rhinorrhea, epistaxis, epiphora, proptosis, photophobia, visual loss, lymphadenopathy, facial paresthesia, or other cranial nerve involvement, as well as acute systemic symptoms such as fatigue, fever, weight loss, bone pain, or abdominal pain.

Diagnosis of olfactory neuroblastomas, also known as esthesioneuroblastomas or olfactory neuroepitheliomas, is often delayed because of the nonspecific symptoms. Olfactory neuroblastomas have a bimodal age distribution, with one peak occurring in the second decade (age 11-20 years) and another in the sixth decade.9

EPISTAXIS: ETIOLOGY AND MANAGEMENT

The most common cause of epistaxis is local trauma (“nose picking”), and several episodes of epistaxis often occur over the course of a few days. Most episodes of epistaxis in children originate in veins along the anterior nasal septum, which includes Kiesselbach plexus, and most acute episodes can be managed with local pressure.

There are many superstitions about how to control acute episodes of epistaxis, and families often need instruction in proper techniques. Because the most common site of bleeding in children is along the anterior septum, using the thumb and forefinger to apply gentle but consistent pressure between the ala and the tip of the nose below the nasal bones is often effective. Application of oxymetazoline, if possible, may be helpful. Afterward, antibiotic ointment can be gently applied inside the nasal vestibule nightly for a week to decrease itching and crusting and promote healing.

Persistent epistaxis may require application of topical hemostatic agents, dissolvable hemostatic products, nasal packing, or cautery. Control of epistaxis may require the use of general anesthesia. Less frequently, and rarely before adolescence, procedures such as arterial ligation or embolization, laser ablation, or dermal grafting may be considered.

If epistaxis is chronic or severe, contributory factors should be considered. If symptoms are persistent or there are other factors in the child’s or the family’s history that suggest an underlying coagulopathy, laboratory evaluation is indicated to identify bleeding disorders.

ACQUIRED NASAL ABNORMALITIES

Nasal Trauma

Nasal trauma is a frequent occurrence during an active childhood, especially among males, and fractures, septal hematomas, and septal abscess may occur as a consequence of minor trauma, sport injuries, and, particularly in young children, abuse. If a nasal fracture results in visible deformity or nasal obstruction, the fracture should be reduced, usually under general anesthesia and sometimes with the placement of an internal or external splint. Children with nasal trauma should also be evaluated for the possibility of a septal hematoma or septal abscess if they have persistent nasal obstruction, pain, rhinor-rhea, or fever.

Nasal Septum Deviation

Nasal septum deviation can result from trauma as noted above. It may also be “congenital” presumably being due to trauma sustained from intrauterine molding or during vaginal delivery. Deviated septum is present in about 10% of patients with Marfan syndrome. Nasal septal deviation, especially when located in the region of the nasal valve, can cause significant nasal airway obstruction; posterior deformities are generally less symptomatic. If symptomatic, in most cases a deviated septum can be corrected with a minor surgical procedure, septoplasty.

Other Acquired Disorders

Less commonly, acquired deformities may affect the nasal vestibule, columella, or nasopharynx. For premature infants with pulmonary disease, continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) applied via nasal prongs is often used to avoid the need for intubation or tracheotomy. In a small percentage of these infants, the nasal CPAP system can result in alar deformity, erosion or transection of the nasal columella, or scarring and subsequent narrowing of the nose within the nostril. Likewise, in children of any age who require nasotracheal intubation or nasogastric tubes, careful attention must be paid to how tape is used to secure the tube to the nose and face to prevent damage to the nasal ala, which may be hidden beneath the tape.

Atrophic rhinitis with ozena, which is characterized by fetid rhinorrhea and nasal crusting, may begin in childhood and progress to atrophy of the nasal mucosa and underlying bone, interfering with nasal airflow. This appearance to the nasal cavity in adolescents may signal the illicit use of cocaine or “crack” glue sniffing, and other chemical inhalants should be considered.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree