Appendicitis

If appendicitis is in the differential diagnosis preoperatively, laparoscopy should be performed. A 12-mm Hasson trocar should be placed at the umbilicus with two additional 5-mm trocars in the suprapubic midline and left lower quadrant. The patient should be positioned with the right side up. If the appendix is grossly inflamed and dilated in the absence of other pathology, the appendix should be removed. The appendix should be gently grasped with a Babcock clamp. The mesoappendix can be transected using hemostatic clips or vessel-sealing device or with an endoscopic linear stapler. A stapler should be used to transect the appendix at the base of the cecum. The specimen can then be pulled through the umbilicus in a bag or glove to avoid wound contamination. If there is gross purulence due to perforation, the area should be copiously irrigated with saline prior to closure. If a phlegmon is encountered in the right lower quadrant and the cecum is involved, it is reasonable to abort the procedure and treat the appendicitis with intravenous antibiotics and percutaneous drainage if an abscess develops. Surgery in this setting is associated with higher morbidity. If an organized abscess is seen, placement of a drain at the time of surgery is suggested; in the case of a phlegmon, no drain is recommended.

Diverticular Disease

Diverticulosis is common among Americans, with prevalence rates up to 45%. Diverticulitis is inflammation of the diverticulum, usually occurring in the sigmoid colon, and it is generally managed nonoperatively. Uncomplicated diverticulitis accounts for 75% of all cases and is initially treated with bowel rest, antibiotics, and possible hospitalization (

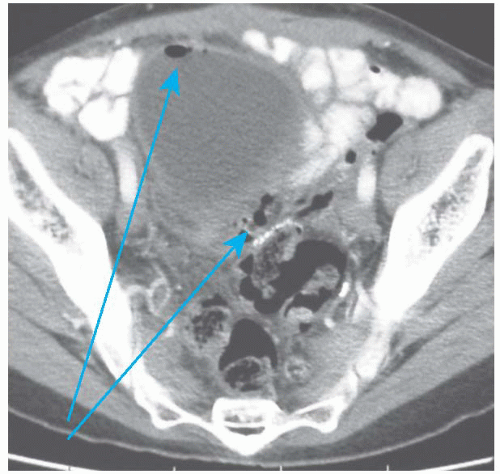

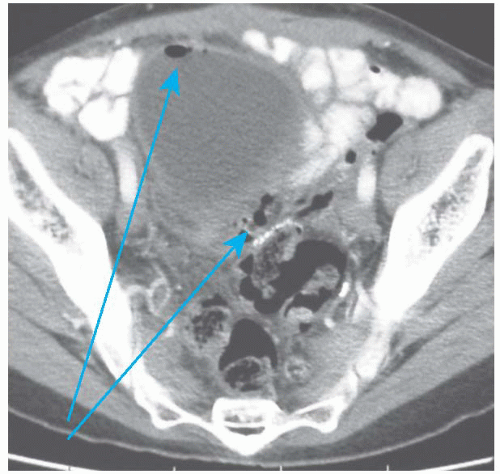

Fig. 48.1). Only when the attacks become recurrent and frequent enough to affect lifestyle is elective sigmoid resection entertained. Complicated diverticulitis (presence of abscess, perforation, fistula, or stricture) generally requires surgery (

Figs. 48.2,

48.3 and

48.4). These cases often present to, or are referred to, a gynecologist because pain localizes to the pelvis and imaging demonstrates a pelvic mass, so a high index of suspicion is required when evaluating patients with preoperative gastrointestinal symptoms or systemic signs of infectious etiologies. When a contained abscess is seen on CT imaging, percutaneous drainage is attempted (

Fig. 48.5). Surgery is ideally performed a few weeks after drain removal in an effort to avoid an end or diverting stoma. Patients with an acute perforation will present with an acute abdomen and require emergency surgery (

Fig. 48.6).

If inactive diverticulosis is found intraoperatively, it should be ignored. Diverticulosis is common, and the majority of patients will never require resection. If the patient has acute diverticulitis or chronic smoldering diverticulitis, it is reasonable to consider a sigmoid resection. The technique of sigmoid resection is outlined in the Steps in the Procedure box.

In order to avoid recurrence of diverticulitis, it is critical that the surgeon resects the entire sigmoid colon and perform the anastomosis between the soft and nonedematous descending colon and the upper rectum. It is not necessary to resect all of the diverticula from the proximal colon. Mobilization of the splenic flexure may be required to perform an anastomosis without tension. If the setting of significant inflammation around the new connection, it is prudent to consider a temporary proximal diversion. If the tissue quality is poor (due to inflammation, edema, size mismatch, etc.), a Hartmann procedure is the safest approach.

Diverticulitis with an abscess involving the adnexa can sometimes be mistaken for a tuboovarian abscess, and this should always be in the differential diagnosis of a pelvic mass in the older female patient. In such cases, moderate elevation of CA-125 is common secondary to inflammation, which can further complicate the diagnostic challenge.

Colorectal Cancer

Cancers of the colon are common with over 100,000 new diagnoses in the United States every year. Ninety percent of colon cancers occur after the age of 50, but they can occur in every age group. Surgical resection is the primary treatment colon and rectal cancer. If a cancer of the colon is unexpectedly encountered intraoperatively, a decision should be made as to whether to proceed with bowel resection immediately or close the abdomen and perform the definitive surgery at a later date. If an operating surgeon experienced in oncologic colon resections is immediately available, then resection and primary anastomosis can be done. As stated before, mechanical bowel preparation is not necessary, but enemas are generally given preoperatively to empty the colon of the bulk of the stool for a left-sided resection. The most frequent tumors unexpectedly encountered by the gynecologic surgeon are cecal (

Figs. 48.7 and

48.8) or rectosigmoid in location. Due to locations, these can often be mistaken for an adnexal mass. Techniques for each are described in the “Steps in the Procedure” boxes. The liver and peritoneal surfaces should be closely inspected for metastatic lesions prior to closure of the abdomen.