17.3 Neuromuscular disorders

The management of neuromuscular disorders requires recognition, diagnosis, therapy and counselling.

Recognition that a child’s presenting symptoms or signs may be due to peripheral neuromuscular disease

Common presenting complaints of neuromuscular disorders include:

Diagnosis of neuromuscular disease based on anatomical, electrophysiological, biochemical, histopathological or DNA identification

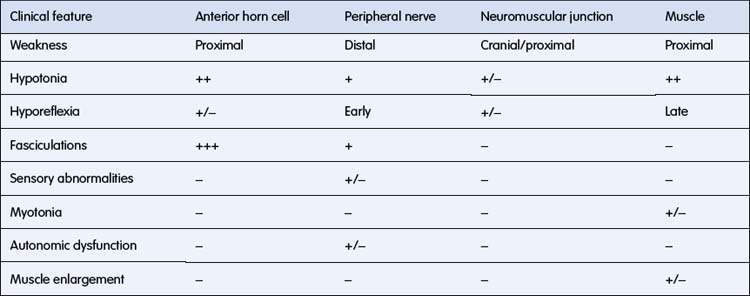

The anatomical localization is based on the clinical findings listed in Table 17.3.1 and includes disorders affecting the:

The definitive diagnosis rests on a combination of:

• clinical history and examination

• serum muscle enzymes, particularly creatine kinase (CK)

• electrophysiology (e.g. nerve conduction studies, electromyography, repetitive nerve stimulation)

• histology of muscle and/or nerve

• metabolic studies (e.g. muscle glycogen, carnitine assay, mitochondrial studies)

Anterior horn cell disorders

Chronic

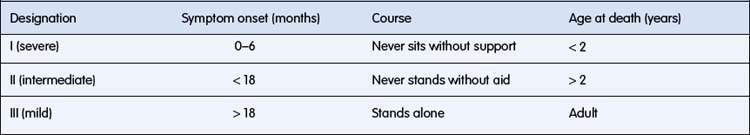

In childhood the chronic disorders characterized pathologically by degeneration of anterior horn cells and associated clinically with progressive muscle weakness are called the spinal muscular atrophies (SMAs). The important SMA syndromes and their classification are listed in Table 17.3.2.

Spinal muscular atrophy type I (Werdnig–Hoffmann disease)

This autosomal recessive disorder occurs in approximately 1 in 6000 live births, making it the most common fatal autosomal recessive disorder of early childhood. The earliest symptom may be decreased fetal movements in late pregnancy. Presentation is invariably before 6 months of age and is either at birth with hypotonia, weakness, joint deformity and respiratory difficulty, or more commonly later with marked hypotonia and limb weakness, poor feeding, poor cough and cry. The onset is sometimes relatively rapid and when first seen the child is usually severely weak (Fig. 17.3.1). Weakness, although generalized, is maximal proximally in the shoulder and hip girdle muscles. Intercostal muscle weakness leads to chest deformity, a poor cough and a weak cry. The respiratory pattern becomes diaphragmatic. Deep tendon reflexes are absent. Fasciculations of the tongue are an important clinical clue, but this can be a difficult sign to be certain about and one can only be confident if the baby is relaxed and there are no ‘voluntary’ movements of the tongue. Facial weakness in SMA is very mild and the extraocular movements remain full, giving the baby an alert appearance. Death, usually from pneumonia and respiratory failure, occurs by 18 months of age in 95% of patients, with those with onset in the first 2 months of life having the shortest survival.

• Tongue fasciculations can be seen with certainty only when the tongue has no voluntary movement, i.e. is at rest in the floor of the mouth and the child is not crying or actively moving the tongue.

• The presence of deep tendon reflexes makes it extremely unlikely that the child has type 1 SMA and an alternative diagnosis should be considered.