SEIZURES IN THE PREGNANT PATIENT

Key Points

• Pregnancy is not contraindicated in women with epilepsy (WWE).

• Greater than 90% of WWE have favorable pregnancy outcomes.

• In most cases, antiepileptic drugs (AED) should be continued during pregnancy.

• Both seizures and AED are associated with increased risk of adverse outcomes of pregnancy.

• Goal for treatment in pregnancy is seizure freedom with the lowest effective AED dose.

• Avoid AED polytherapy when possible.

• Valproic acid (VPA) exposure during pregnancy is associated with significantly greater risks than other AED exposures.

• Folic acid supplementation is recommended prior to conception and during pregnancy.

• Pregnant WWE should be managed jointly by their neurologist and obstetrician.

Background

Definitions

• A seizure is a sudden, abnormal synchronous electrical discharge of cerebral neurons.

• Seizures may be provoked (toxic, metabolic, infectious, etc.) or unprovoked.

• Symptoms vary depending on the area of brain involved.

Brief change in awareness and/or behavior

Brief change in awareness and/or behavior

Abnormal movement: tonic posture, clonic jerking, myoclonic jerks, loss of muscle tone, etc.

Abnormal movement: tonic posture, clonic jerking, myoclonic jerks, loss of muscle tone, etc.

May be followed by postictal confusion

May be followed by postictal confusion

• Epilepsy is defined as ≥2 unprovoked seizures greater than 24 hours apart.

• Focal seizures (aka partial seizures) begin in a localized area of the brain and may or may not spread to involve other regions of the brain. Focal seizures may occur with or without impairment of consciousness or awareness; with observable motor or autonomic components, such as twitching or jerking, flushing, or automatic behaviors called automatisms (e.g., lip smacking or picking); or involving subjective sensory or psychic phenomena only (also called an “aura”). Focal seizures may spread to diffuse brain involvement, leading to a convulsion, such as a tonic–clonic seizure (1).

• Generalized seizures involve nearly all of the brain at onset and include generalized tonic–clonic (GTC), tonic or atonic (“drops”), myoclonic, and absence seizure types (1).

Risk Factors

• Some epilepsy syndromes have a genetic component.

• Other epilepsy risk factors include traumatic brain injury, stroke, brain tumor or other cerebral structural abnormality, congenital or developmental neurologic disorder, or degenerative disorder.

Epidemiology

• Epilepsy affects approximately 1% of the population (2).

• Greater than 1 million WWE of reproductive age in the United States give birth to greater than 24,000 infants each year (3).

Evaluation

History

• Proper evaluation of a woman with epilepsy should begin prior to pregnancy.

• Essential information includes

• Certainty of the diagnosis of epilepsy—is further diagnostic evaluation required?

• Is the woman followed regularly by a neurologist?

• The seizure type, frequency, intensity, and duration should be assessed.

• Identify current AED treatment:

Evaluate compliance, efficacy, and adverse effects.

Evaluate compliance, efficacy, and adverse effects.

Is she a candidate to discontinue AED prior to conception?

Is she a candidate to discontinue AED prior to conception?

• Are there any other associated neurologic disorders?

• Does she have any complications related to seizures or AED that occurred in prior pregnancies?

• Is she taking supplemental folic acid?

• Is pregnancy desired or planned, or is the woman already pregnant?

• If pregnancy is not desired, what (if any) is the method of contraception?

• If pregnancy is desired (or possible), is she taking supplemental folic acid?

• If the woman is pregnant

What is the stage of gestation?

What is the stage of gestation?

Has she continued her AED treatment?

Has she continued her AED treatment?

Has there been any change in seizure frequency or intensity?

Has there been any change in seizure frequency or intensity?

Is she taking supplemental folic acid?

Is she taking supplemental folic acid?

Diagnosis

• In women with a well-established epilepsy diagnosis, the diagnosis is ordinarily not an issue for the obstetrician. However, certain important scenarios make diagnosis an issue.

• In patients with well-established epilepsy, the appearance of clinical spells different from the patient’s usual seizures may indicate another disorder.

• A few patients will experience new-onset seizure disorder during pregnancy.

• The differential diagnosis of seizures includes many other kinds of clinical “spells” including: syncope, panic attacks, psychogenic nonepileptic seizures, episodic vertigo, paroxysmal movement disorders, and others. These attacks are sometimes difficult to distinguish from epileptic seizures, and expert consultation may be needed.

• Correct diagnosis is important:

• Nonepileptic events are not effectively treated with AEDs.

• Use of AED for nonepileptic events exposes the mother and baby to risks of AED therapy with no concomitant benefit.

• Treatment for the correct diagnosis will be delayed.

• If the obstetrician observes an attack, it is important to obtain as detailed a description as possible. Particular attention should be paid to the onset of the attack, its clinical characteristics, its duration, and any postattack symptoms.

• If a woman develops a seizure disorder during pregnancy, a complete evaluation should be performed by a neurologist to establish a diagnosis and search for an underlying cause.

Treatment

General Principles

• Every effort should be made to maintain seizure control during pregnancy and delivery.

• Most WWE require continuing AED treatment prior to, during, and after pregnancy and delivery.

• The best AED for a given patient is an AED appropriate for the patient’s seizure type, which provides best seizure control at the lowest dose and with the fewest side effects.

Risks

WWE taking AED are at greater risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes related to teratogenicity, cognitive effects in the children exposed in utero to AED, seizures during pregnancy, and possibly increased rates of some obstetrical complications.

Major Congenital Malformations

• The vast majority of WWE will have babies with no malformations.

• The most common major congenital malformations (MCM) occurring in infants of WWE on AED include congenital heart disease, cleft lip/palate, neural tube defects, and urogenital defects (3).

• The overall risk of MCM in WWE taking AED is approximately 3% to 9%, or approximately two to four times the risk in the general population (3).

• Approximately 2% to 8% risk of MCM with any first-trimester monotherapy AED exposure (3)

• Approximately 6.5% to 19% risk of MCM with any first-trimester polytherapy AED exposure (3)

• MCM risk is significantly higher with first-trimester monotherapy or polytherapy including VPA compared to other monotherapy AED exposure or polytherapy without VPA (3).

• First-trimester topiramate (TPM) exposure is associated with a greater risk of cleft lip (4).

• Greater risk of MCM is associated with higher first-trimester VPA, lamotrigine (LTG), and phenobarbital (PB) doses.

VPA doses above approximately 1000 mg/d or levels greater than 70 μg/mL (5)

VPA doses above approximately 1000 mg/d or levels greater than 70 μg/mL (5)

LTG doses ≥300 mg/d (6)

LTG doses ≥300 mg/d (6)

PB doses ≥150 mg/d (6)

PB doses ≥150 mg/d (6)

Cognitive Outcomes in Children of Women with Epilepsy

• In utero exposure to VPA is associated with reduced cognitive abilities measured in children at ages 3, 4.5, and 6 years, and the effect is dose dependent (7–9).

• In utero VPA exposure is associated with significantly increased absolute risk (4.4%) of autism spectrum disorders in children compared with those not exposed to VPA (2.4%) (10).

• Use of periconceptional folic acid by WWE on AED is associated with significantly higher IQ scores in their children at age 6 years (7).

Obstetrical Complications and Perinatal Outcomes

• Rigorous literature reviews have raised concern for possible increased obstetrical complications and adverse perinatal outcomes in WWE.

• There may be a modestly increased risk (up to 1.5 times expected) of cesarean delivery for WWE on AED (11).

• An increased risk (greater than 2 times expected) of premature contractions and premature labor and delivery (L&D) in WWE who smoke has also been reported (11).

• Insufficient evidence exists to support or refute increased risk of preeclampsia, pregnancy-related hypertension (HTN), or miscarriage (11).

• WWE taking AED are at increased risk of having small for gestational age neonates, approximately 2 times expected rate (5).

• There is probably no substantially increased risk (greater than 2 times expected) of perinatal death in newborns of WWE (5).

Vitamin K Supplementation

• There is insufficient evidence to support or refute increased risk of neonatal hemorrhagic complications in newborns of WWE on AED or decreased risk when these women are treated with prenatal vitamin K supplementation (12).

• Newborns of WWE taking enzyme-inducing AED (EIAED) (phenytoin [PHT], carbamazepine (CBZ), PB, primidone [PRM]) routinely receive vitamin K at delivery, as do all newborns.

Effect of Maternal Seizures on the Fetus

• GTC seizures pose a risk to the fetus, as well as to the mother.

• Maternal and fetal hypoxia and acidosis (3).

• Fetal intracranial hemorrhage, miscarriage, prolonged fetal heart rate (HR) depression (greater than 20 minutes), and stillbirths have been reported following GTC seizures (3).

• Effects to the fetus from nonconvulsive seizures are less clear.

• There are case reports of fetal HR decelerations (3).

• There is risk of trauma with multiple seizure types, potentially leading to perinatal complications.

Seizure Frequency During Pregnancy

• Most WWE (64%) have unchanged seizure frequency during pregnancy (3).

• Sixteen percent have fewer seizures in pregnancy compared to baseline.

• Seventeen percent have an increase in seizure frequency during pregnancy.

• Studies observing seizure frequency in pregnant WWE have not included a control group of nonpregnant WWE with seizure frequency data for comparison. Thus, the influence of pregnancy on seizure frequency is unclear (11).

• Seizure freedom ≥9 months prior to conception is associated with high likelihood (84% to 92%) of seizure freedom during pregnancy (11).

• There is insufficient evidence to support or refute increased risk of status epilepticus (SE) in pregnancy (11).

Laboratory Tests

• AED levels can provide important guidance in managing AED therapy before, during, and after pregnancy. However, physicians should

• Evaluate seizure control, not an AED level, to determine AED effectiveness

• Be cognizant that drug toxicity is a clinical diagnosis, which may or may not correlate with “toxic” blood levels

Contraceptive Management

• Oral contraceptives (OC) per se have no effects on seizure frequency.

• Estrogen may lower serum levels of LTG up to 50%, potentially leading to breakthrough seizures (13,14).

• EIAED, including PHT, PB, PRM, CBZ, felbamate (FBM), clobazam (CLB), and rufinamide (RUF), may reduce hormone levels, leading to contraceptive failure. Oxcarbazepine (OXC) greater than 1200 mg/d and TPM greater than 200 mg/d have a similar effect. It has been recommended WWE taking these agents should take OC with ≥50 μg estradiol or its equivalent, though no studies have determined whether this improves the risk of contraceptive failure in the setting of EIAED. Transdermal patch and vaginal ring formulations and intramuscular (IM) medroxyprogesterone also have higher failure rates. An 8- to 10-week dosing interval for IM medroxyprogesterone in the setting of EIAED has been suggested, though whether this improves efficacy has not been established (3,14).

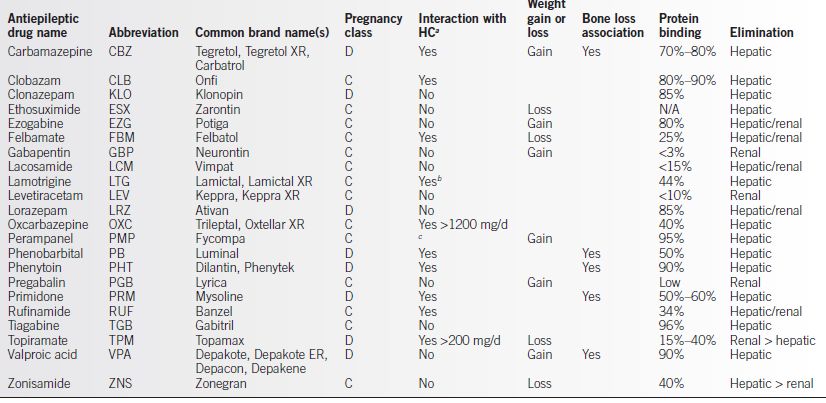

• Perampanel (PMP) reduces levonorgestrel levels by up to 40% (see Table 24-1).

Table 24-1 Antiepileptic Drug Therapy in Women

aHC, hormonal contraceptive

bLTG levels may be reduced greater than 50% in the presence of estrogen-based contraceptives, leading to risk of increased seizures when HC is added. LTG does not appear to significantly affect efficacy of HC.

cPMP reduces levonorgestrel levels by up to 40%.

Prepregnancy Management

• Any uncertainty about the diagnosis of epilepsy should be resolved. Consultation with a neurologist should be obtained and continued through pregnancy.

• If seizure free greater than 2 years on AED with normal imaging, electroencephalography (EEG), and exam, consider whether the patient is a candidate to wean off AED under care of neurologist, dependent on epilepsy syndrome diagnosis. If electing to wean AED, counsel regarding risk of seizure recurrence. This should be accomplished ≥6 months prior to conception.

• Consider changing to an alternative to VPA therapy, if possible prior to conception (5).

• Consider converting from polytherapy to monotherapy prior to conception if possible (5).

• Due to high risk of unplanned pregnancy, all women of childbearing age on AED should be given supplemental folate. The ideal dose is unclear due to lack of rigorous evidence with respect to dosing. Current guidelines from the American Academy of Neurology recommend a minimum of 0.4 mg daily prior to conception and during pregnancy, but other experts, including the American and Canadian Obstetricians and Gynecologists organizations, have recommended higher doses, up to 4 to 5 mg/d (3).

Management During Pregnancy

• Once pregnancy is established, there is little or no benefit, and some risk, of changing an established treatment regimen.

• The fetus has already been exposed to the current AED, during at least part of the most sensitive stage of gestation, prior to the patient’s seeking medical attention.

• A change in medication may increase the risk of maternal seizures.

• Overlapping two AEDs during the change exposes the fetus to the risks of a second AED and added risk of polytherapy.

• Physicians should suggest that their patients register with the North American Antiepileptic Drug Pregnancy Registry (www.aedpregnancyregistry.org).

• Compliance with AED and supplemental folic acid should be encouraged.

• Maternal serum screening, ultrasound imaging, and other appropriate studies to identify MCM should be considered.

• Normal L&D can be anticipated.

• Some WWE may have other neurologic disorders, which may complicate L&D.

• One percent to two percent of WWE experience seizures during L&D; another 1% to 2% experience seizures within 24 hours of delivery. Idiopathic generalized epilepsy has been associated with greater risk (12.5%) of seizures during L&D (3).

• Emergency cesarean delivery may be needed for WWE with refractory seizures during labor.

Antiepileptic Drug Levels During Pregnancy

• The effect of pregnancy on AED levels is complex:

• Total levels of AED typically decline during pregnancy due to

Increased blood volume

Increased blood volume

Increased hepatic and renal clearance of most AED

Increased hepatic and renal clearance of most AED

• For some AED with high protein binding, non–protein-bound drug levels (“free levels”) may remain constant or increase due to decreased plasma protein binding. Free levels reflect the active fraction of the drug (Table 24-1) (3).

PHT free levels decrease 15% to 40% in the third trimester.

PHT free levels decrease 15% to 40% in the third trimester.

CBZ free levels do not significantly change during pregnancy.

CBZ free levels do not significantly change during pregnancy.

VPA free levels increase in the second and third trimesters.

VPA free levels increase in the second and third trimesters.

PB free levels decrease 50% in pregnancy.

PB free levels decrease 50% in pregnancy.

• LTG clearance increases by 65% to 230% during pregnancy with significant variability between patients. Decreasing LTG concentration in pregnancy has been associated with increased seizure frequency (12).

• The active metabolite of OXC, monohydroxy derivative, decreases 36% to 61% during pregnancy, and WWE on OXC may be at greater risk for convulsive seizures (3).

• Levetiracetam (LEV) concentrations may decrease by 60% in the third trimester (3).

• AED levels should be measured

• Prior to conception (baseline)

• At the beginning of each trimester

• During the last 4 weeks of pregnancy

• Additional monitoring may be needed if there is a change in seizure frequency or if clinical side effects appear.

• More frequent monitoring of certain AED levels may be indicated when a greater magnitude of change from baseline is expected or observed; dosage adjustment to maintain levels similar to prepregnancy baseline may be considered.

• Non–protein-bound (“free”) drug levels should be obtained when available.

Postpartum Management

Antiepileptic Drugs

• AED levels may rise rapidly in the weeks after delivery due to decreasing blood volume, decreased hepatic/renal clearance, and altered protein binding, resulting in possible toxicity in the absence of appropriate dosing adjustments (3).

• Most AED levels return to baseline within 10 weeks after delivery (3).

• Drug levels and clinical response should be followed closely.

• LTG levels increase more rapidly following delivery as LTG clearance returns to baseline within 2 to 3 weeks. Careful dosing adjustment and monitoring for toxicity beginning within several days postpartum are suggested (3).

• Drug withdrawal may occur in babies exposed to PB during gestation.

• Neonates exposed to EIAED in utero should be observed for clotting disorders.

Breast-feeding

• All AEDs are present in breast milk to some extent.

• Highly protein-bound AED will be present at lower concentrations than others (see Table 24-1).

• The benefits of breast-feeding are considered to outweigh the relatively small risk of AED adverse effects in infants (3).

• Newborns have immature drug elimination systems, and infants should be observed for signs of drug intoxication (lethargy, poor feeding, irritability, etc.).

• One large study examining cognitive outcomes in children of WWE following in utero CBZ, LTG, PHT, and VPA exposure found no adverse effect of breast-feeding on IQ at age 3 for all AED combined or for each of the four individual AED groups (15).

Child Care and Seizure Precautions

• Recommend close supervision by another adult for WWE when bathing infant, or give sponge bath.

• Changing/dressing infant on pad on the floor is safer than using a changing table.

• WWE who have uncontrolled seizures with loss of awareness or falls should consider use of a sling or small lightweight stroller when moving about the house with baby.

• For WWE with uncontrolled seizures, it may be safest to have another adult present to ensure safety of mother and infant, depending on seizure type and frequency.

COMPLICATIONS

Status Epilepticus

• SE is defined as continuous seizure activity for ≥30 minutes or repeated seizures over a ≥30-minute period without full recovery between attacks.

• A presumptive diagnosis of SE is made when seizures last ≥5 minutes or when two or more discrete seizures occur without return to baseline in between.

• SE is a medical emergency and requires prompt diagnosis and treatment.

Mortality in SE ranges from 3% to 32% and depends largely on the underlying cause, severity of the seizures, and SE duration (16).

Mortality in SE ranges from 3% to 32% and depends largely on the underlying cause, severity of the seizures, and SE duration (16).

Mortality in uncomplicated SE is approximately 3% (16).

Mortality in uncomplicated SE is approximately 3% (16).

Control of SE becomes increasingly difficult as its duration increases.

Control of SE becomes increasingly difficult as its duration increases.

• Management of SE requires multiple measures, carried out virtually simultaneously:

• Protect the patient from injury; avoid mechanical restraints

• ABCs—airway, breathing, circulation: O2, IV, cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), and intubation if required

• Consider thiamine 100 mg + 50 mL D50% IV

• Assess the likely causes of SE:

Withdrawal of anticonvulsant drugs (including noncompliance)

Withdrawal of anticonvulsant drugs (including noncompliance)

Withdrawal from drugs or alcohol

Withdrawal from drugs or alcohol

Metabolic derangements (e.g., electrolyte or glucose abnormalities)

Metabolic derangements (e.g., electrolyte or glucose abnormalities)

Eclampsia (see Chapter 11)

Eclampsia (see Chapter 11)

Central nervous system (CNS) infections, head trauma, etc.

Central nervous system (CNS) infections, head trauma, etc.

• Obtain blood specimen for glucose, electrolytes (including Ca, Mg, phosphorus), complete blood count (CBC), liver function test (LFTs), AED levels, arterial blood gas (ABG), troponin, and toxicology studies.

• Lumbar puncture is indicated only when meningitis is suspected, and empiric antibiotic therapy should be started immediately.

• Imaging studies should be delayed until the seizures are controlled.

• Continuous EEG is indicated to aid in diagnosis and management.

• Drug treatment of SE

• For continuous or nearly continuous seizures, lorazepam IV in 2-mg increments every 2 minutes while seizure is ongoing up to maximum dose 0.1 mg/kg is the drug of choice. If rapid IV access is not available, give midazolam 10 mg IM, fosphenytoin (not phenytoin) IM, or diazepam 20 mg per rectum (PR).

• For ongoing or intermittent seizures, or following termination of SE with benzodiazepines, use fosphenytoin 20 mg/kg PE (phenytoin equivalent) IV at 100 to 150 mg/min with BP and EKG monitoring. If necessary, additional fosphenytoin, up to 10 mg/kg, can be given.

• If fosphenytoin fails to control seizures, reasonable options include

LEV 1000 mg IV over 15 minutes, repeat × 1 if still seizing.

LEV 1000 mg IV over 15 minutes, repeat × 1 if still seizing.

PB 20 mg/kg IV at 50 mg/min.

PB 20 mg/kg IV at 50 mg/min.

Initiate continuous IV infusion with midazolam, pentobarbital, or propofol, or give inhalation anesthesia if seizures persist. Few controlled comparison studies are available.

Initiate continuous IV infusion with midazolam, pentobarbital, or propofol, or give inhalation anesthesia if seizures persist. Few controlled comparison studies are available.

Intubation and ventilator support will probably be needed.

Intubation and ventilator support will probably be needed.

Monitor closely for hypotension.

Monitor closely for hypotension.

• Advice and/or consultation from a neurologist or specialist in critical care medicine should be obtained as soon as possible.

• SE due to eclampsia should be managed as outlined in Chapter 11.

NEW-ONSET SEIZURES

• Occasionally, patients experience their first seizures during pregnancy (other than as part of eclampsia syndrome). Urgent issues facing the physician and patient include

• Was the event an epileptic seizure or a nonepileptic event?

• What is the likelihood of recurrence?

• Is there an associated medical or neurologic disorder?

• Is anticonvulsant drug treatment needed?

• Evaluation

• Consider neurological consultation.

• Differential diagnosis for new-onset seizure includes nonepileptic events such as hypoglycemia, hyperventilation, panic attack, syncope, and psychogenic nonepileptic seizure, as well as epileptic seizure.

Obtain as detailed a description of the event as possible. Features typical of epileptic seizures include

Obtain as detailed a description of the event as possible. Features typical of epileptic seizures include

– Abrupt onset and offset.

– Brief duration (a few minutes or less).

– Motor activity (if present) is not purposeful.

– Little or no recall for the details of the attack.

– Postictal confusion and lethargy.

Was the attack truly a first seizure?

Was the attack truly a first seizure?

– Is there a prior history of staring spells, transient loss of awareness, or childhood seizures?

– Is there a history of unexplained nocturnal incontinence, tongue biting, or other injury?

• Is there evidence for any underlying medical or neurologic disorder?

Evaluate with detailed history, physical and neurologic examinations.

Evaluate with detailed history, physical and neurologic examinations.

– Computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be done safely during pregnancy if necessary (17).

The need for laboratory studies, toxicology screening, etc. should be determined by the clinical setting.

The need for laboratory studies, toxicology screening, etc. should be determined by the clinical setting.

EEG is often helpful.

EEG is often helpful.

• Is AED treatment needed?

• In the case of a single seizure for which no cause is identified, in an otherwise healthy patient with normal imaging and EEG, AED treatment should be deferred.

• If a specific medical cause for the seizure is identified, the underlying cause should be treated.

• In the case of recurrent seizures, or in cases where evaluation suggests a high likelihood of recurrent seizures, anticonvulsant treatment should be initiated.

• For all patients, regardless of whether or not treatment is started

Patients should be counseled about the risks of recurrent seizures and the risks of AED to them and to their babies.

Patients should be counseled about the risks of recurrent seizures and the risks of AED to them and to their babies.

Patients should be counseled about safety measures to reduce the risk of injury if additional seizures occur.

Patients should be counseled about safety measures to reduce the risk of injury if additional seizures occur.

Three- to six-month seizure freedom prior to returning to driving is typically required, but state laws vary.

Three- to six-month seizure freedom prior to returning to driving is typically required, but state laws vary.

Patient Education

• Reassure patients that the vast majority of women with seizures have healthy babies, even when treated with AED during pregnancy and even if they have seizures during pregnancy, labor, or delivery.

• Women with seizures should be strongly encouraged to meet with their physicians at least 6 months prior to a planned pregnancy so that any needed alterations to their seizure management can be completed before pregnancy begins.

• Women should be advised to take folic acid prior to, during, and after pregnancy.

• Women should be encouraged to continue their AED in the event of an unplanned pregnancy. Sudden withdrawal of AED is much more likely to be harmful than beneficial, both to the mother and to the baby.

• Mothers should be encouraged to promptly report any change in the frequency, character, or intensity of their seizures to their obstetrician and to their neurologist.

HEADACHES (HA) IN THE PREGNANT PATIENT

Key Points

• All headaches (HA) should be taken seriously, since even medically “benign” HA may cause severe distress and disability.

• Physicians should be especially alert to HA of recent onset or a sudden change in the character of a previously stable HA syndrome.

• In patients with chronic HA, a realistic goal of management is 50% reduction in the frequency and severity of HA. Cure of the HA is rarely achieved.

Background

• HA management, especially in pregnant patients, is often difficult and frustrating for both physicians and patients.

• HA pain (like all pain) is subjective, with no objective criteria to measure the success or failure of treatment.

• Many of the standard agents used in the prophylaxis and treatment of HA are at least relatively contraindicated in pregnancy.

• The goal of treatment is often satisfactory management of a chronic condition rather than cure of an acute condition.

• Treatment often includes chronic use of medications with high abuse potential.

Pathophysiology

• Head pain may originate from either intracranial or extracranial sources.

• Pain-sensitive structures within the skull include the meninges and the larger blood vessels at the base of the brain. The brain itself is largely insensitive to pain. Pain may result from increased intracranial pressure, from distortion or traction of the meninges or blood vessels, or from irritation of the meninges.

• Pain-sensitive structures outside the skull include the muscles of the face and scalp, the blood vessels of the face and scalp, the mucosal lining of the sinuses, and the skin and subcutaneous tissues of the face and scalp.

• Head pain is often referred, and patients often cannot distinguish the source of their pain. Pain perceived by the patient as coming from deep inside the head may in fact be coming from an extracranial source.

Evaluation of the Patient with Headache

History

• Is there a prior history of HA? If so, is the current HA problem consistent with the previous HA syndrome or is it a new problem?

• Obtain a description of the HA: location, intensity, frequency, character (steady, throbbing, stabbing, squeezing, etc.). Is the HA provoked or relieved by activity, position, medications, time of day, etc?

• Are there any premonitory symptoms, such as changes in vision, numbness or weakness of the extremities, etc., before the HA begins?

• Are there associated symptoms, such as nausea and vomiting, photophobia, phonophobia, blurred vision, visual loss or hallucinations, focal neurologic symptoms, etc?

• Is the HA pattern stable, worsening, or improving? Does the HA pattern seem to be acute, subacute, or chronic (see below)?

Physical Examination

• In the majority of patients (especially those with “benign” disease), the physical and neurologic examinations are often normal.

• A careful neurologic examination should be carried out in all pregnant patients with complaint of HA.

Laboratory Studies

• For patients with well-established HA syndromes (e.g., migraine or tension type), routine laboratory and imaging studies, such as CT and MRI scanning, are usually not needed.

• For patients with new-onset HA or those who have a substantial change in the frequency, severity, or clinical features of a previously stable HA pattern, the “worst headache” of their lives (particularly if abrupt in onset), an abnormal neurologic examination, a progressive or new daily persistent HA, EEG evidence of a focal abnormality, or a comorbid partial seizure, a full diagnostic evaluation, including imaging studies, lumbar puncture, or other laboratory studies, may be needed (see below) (18).

ACUTE HEADACHE SYNDROMES

Background

• Acute HA syndromes develop over a short period of time, usually hours to days. Acute HA syndromes raise the greatest concern regarding severe or life-threatening disease.

• An acute HA may be the first attack of migraine or tension HA, which is usually associated with chronic HA syndromes.

• In patients with chronic HA syndromes (see below), an abrupt change in the character of the HA may indicate the development of a new acute HA syndrome.

Subarachnoid Hemorrhage

• Half of all cerebrovascular diseases during pregnancy are caused by subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH).

• SAH is most often due to rupture of an aneurysm of one of the large blood vessels at the base of the brain (“berry aneurysm”); less often from leakage from an arteriovenous malformation or other vascular anomaly. Approximately 10% occur without any identified cause.

• The risk of SAH is increased in late pregnancy and in the puerperium.

• The initial hemorrhage may be catastrophic or fatal for both mother and fetus. The maternal mortality from the initial hemorrhage is approximately 50%.

• Symptoms of SAH include

• Abrupt onset HA, usually severe (not always “worst headache of my life”).

• Nausea, vomiting, photophobia, stiff neck, confusion, and lethargy are common.

• Physical findings may include retinal hemorrhages, elevated blood pressure, fever, stiff neck, or focal neurologic signs, but the exam may be entirely normal.

• CT scanning is diagnostic in greater than 90% of patients with good technique and experienced radiologists. A negative CT scan does not rule out SAH; if the diagnosis is suspected and CT is negative, lumbar puncture is mandatory.

• Major hemorrhages are sometimes preceded by less severe or even minor “sentinel” hemorrhages; prompt recognition and aggressive treatment may prevent subsequent catastrophe. There is a high risk of rebleeding (and death) within a few weeks following the initial hemorrhage. Urgent referral to a neurosurgeon is indicated, and treatment should not be delayed (19).

• If SAH is present, urgent referral to a neurologist or neurosurgeon is indicated. Evaluation and management should not be delayed.

• Cesarean delivery may be indicated if the mother is critically ill, if symptomatic vascular malformation is diagnosed at term, or if the patient has had surgical treatment within the last 8 days. Otherwise, route of delivery should be determined based on obstetric indications (20).

MENINGITIS

• Acute bacterial meningitis is a true medical emergency; untreated, there is virtually 100% mortality for both the mother and the fetus. Viral meningitis usually carries a much less ominous prognosis, and spontaneous recovery is likely.

• The most common causative agent of bacterial meningitis is Streptococcus pneumoniae, most often preceded by otitis or sinusitis. The second most common causative agent is Listeria monocytogenes. In teens and young adults, Neisseria meningitidis is a common cause. Death, miscarriage, stillbirth, and neonatal death are possible complications.

• The classic clinical triad of HA, fever, and stiff neck is not always present; worsening HA associated with fever should always suggest the diagnosis. Malaise, nausea and vomiting, and lethargy and confusion are often present.

• CT and MRI can rule out structural lesions but are not helpful in the diagnosis of acute meningitis.

• If meningitis is suspected, urgent lumbar puncture is mandatory.

• If lumbar puncture cannot be carried out immediately, empiric antibiotic treatment should be started immediately. Empirical therapy should cover S. pneumonia, L. monocytogenes, and N. meningitidis. Adjunctive treatment with dexamethasone may also be appropriate. Treatment should not be delayed waiting for imaging studies, lumbar puncture, etc.

• Recommendations for antibiotic treatment of meningitis are frequently revised. The consultation from an expert in infectious diseases should be obtained (21).

HYPERTENSIVE ENCEPHALOPATHY

• Hypertensive encephalopathy (HE) is characterized by severe HA, impaired consciousness (which may progress to coma), seizures (including SE), and visual field deficits (including cortical blindness), in patients with severe HTN.

• Focal neurologic signs are usually mild and transient; prominent focal signs suggest ischemic stroke or intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) (see below).

• CT imaging is often normal, but MRI may demonstrate extensive areas of edema, especially in the white matter of the parietal and occipital lobes. In this case, the syndrome is also referred to as posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES), posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome (PLES), and other synonyms.

• The underlying pathology in PRES is vasogenic edema. Elevation of blood pressure exceeds the autoregulatory capability of the brain vasculature resulting in endothelial damage, increased permeability, and hydrostatic edema. While the posterior circulation is most susceptible to inadequate autoregulation, other areas, such as the brain stem, cerebellum, basal ganglia, and frontal lobes, can also be involved.

• Treatment consists of aggressive management of severe HTN and seizures (see above and below and Chapters 4 and 11).

• The prognosis is generally good, with most patients making a full recovery. However, deaths and permanent neurologic sequelae may result.

• A similar picture may be seen in patients with HTN related to eclampsia, acute glomerulonephritis, and in those treated with cytotoxic or immunosuppressive drugs (22).

Preeclampsia/Eclampsia

• The International Classification of Headache Disorders-II definition of HA attributable to preeclampsia or eclampsia includes the criteria for preeclampsia or eclampsia (see Chapter 11) and also specifies that

• The HA must be bilateral, pulsating, or aggravated by physical activity

• The HA must develop during episodes of HTN and resolve within 7 days of effective HTN treatment (23)

Post–Lumbar Puncture Headache

• HA may occur after inadvertent dural puncture in patients receiving epidural anesthesia or after spinal anesthesia. Smaller spinal needle size, the use of noncutting spinal needles, and orienting the needle parallel to the longitudinal dural fibers decrease the risk of post–lumbar puncture HA.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree