Neonatal Thrombocytopenia

Chaitanya Chavda

Matthew Saxonhouse

Martha Sola-Visner

I. INTRODUCTION.

Thrombocytopenia in neonates is traditionally defined as a platelet count of less than 150 × 103/mcL and is classified as mild (100-150 × 103/mcL), moderate (50-99 × 103/mcL), or severe (<50 × 103/mcL). However, platelet counts in the 100-150 × 103/mcL range are somewhat more common among healthy neonates than among healthy adults. For that reason, careful follow-up and expectant management in an otherwise healthy-appearing neonate with mild, transient thrombocytopenia is an acceptable approach, although lack of quick resolution, worsening of thrombocytopenia, or changes in clinical condition should prompt further evaluation. The incidence of thrombocytopenia in neonates varies significantly, depending on the population studied. Specifically, while the overall incidence of neonatal thrombocytopenia is relatively low (0.7%-0.9%) (1), the incidence among neonates admitted to the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) is very high (22%-35%) (2—4). Within the NICU, mean platelet counts are lower among preterm neonates than among neonates born at or near term (5), and the incidence of thrombocytopenia is inversely correlated to the gestational age, reaching approximately 70% among neonates born with a weight <1,000 g (6).

II. APPROACH TO THE THROMBOCYTOPENIC NEONATE.

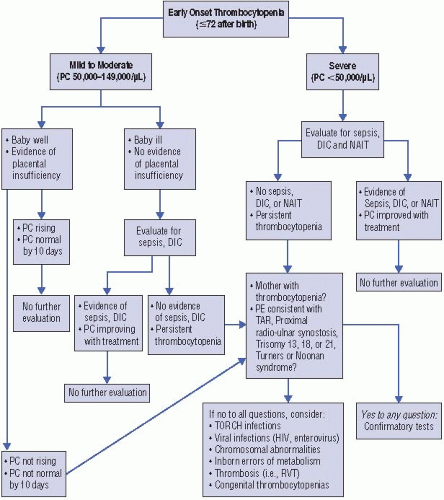

When evaluating a thrombocytopenic neonate, the first step to narrow the differential diagnosis is to classify the thrombocytopenia as either early onset (within the first 72 h of life) or late onset (after the initial 72 h of life), and to determine whether the infant is clinically ill or well. Importantly, infection and sepsis should always be considered near the top of the differential diagnosis (regardless of the time of presentation and the infant’s appearance), as any delay in diagnosis and treatment can have life-threatening consequences.

Early-onset thrombocytopenia (Figure 47.1). The most frequent cause of earlyonset thrombocytopenia in a well-appearing neonate is placental insufficiency, as occurs in infants born to mothers with pregnancy-induced hypertension/preeclampsia or diabetes and in those with intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) (7, 8). This thrombocytopenia is always mild to moderate, presents immediately or shortly after birth, and resolves within 7 to 10 days. If an infant with a prenatal history consistent with placental insufficiency and mild-to-moderate thrombocytopenia remains clinically stable and the platelet count normalizes within 10 days, no further evaluation is necessary. However, if the thrombocytopenia becomes severe and/or persists > 10 days, further investigation is necessary.

Severe early-onset thrombocytopenia in an otherwise healthy infant should trigger suspicion for an immune-mediated thrombocytopenia, either autoimmune

(i.e., the mother is also thrombocytopenic) or alloimmune (i.e., the mother has a normal platelet count). These varieties of thrombocytopenia are discussed in detail below.

Early-onset thrombocytopenia of any severity in an ill-appearing term or preterm neonate should prompt evaluation for sepsis, congenital viral or parasitic infections, or disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). DIC is most frequently associated with sepsis but can also be secondary to birth asphyxia.

In addition to these considerations, the affected neonate should be carefully examined for any radial abnormalities (suggestive of thrombocytopenia-absent radius (TAR) syndrome, amegakaryocytic thrombocytopenia with radioulnar synostosis (ATRUS), or Fanconi anemia). Although thrombocytopenia associated with Fanconi almost always presents later (during childhood), neonatal cases have been

reported (9). In these patients, thumb abnormalities are frequently found, and the diepoxybutane test is nearly always diagnostic. If the infant has radial abnormalities with normal appearing thumbs, TAR syndrome should be considered (10). The platelet count is usually <50 × 103/mcL and the white cell count is elevated in >90% of TAR syndrome patients, sometimes exceeding 100 × 103/mcL and mimicking congenital leukemia. Infants that survive the first year of life generally do well, since the platelet count then spontaneously improves to low-normal levels that are maintained through life (11). The inability to rotate the forearm on physical examination, in the presence of severe early-onset thrombocytopenia, suggests the rare diagnosis of congenital ATRUS. Radiologic examination of the upper extremities in these infants confirms the proximal synostosis of the radial and ulnar bones (12). Other genetic disorders associated with early-onset thrombocytopenia include trisomy 21, trisomy 18, trisomy 13, Turner syndrome, Noonan syndrome, and Jacobsen syndrome.

The presence of hepato- or splenomegaly is suggestive of a viral infection, although it can also be seen in hemophagocytic syndrome and liver failure from different etiologies. Other diagnoses, such as renal vein thrombosis, Kasabach—Merritt syndrome, and inborn errors of metabolism (mainly propionic acidemia and methylmalonic acidemia), should be considered and evaluated based on specific clinical indications (i.e., hematuria in renal vein thrombosis, presence of a vascular tumor in Kasabach-Merritt syndrome).

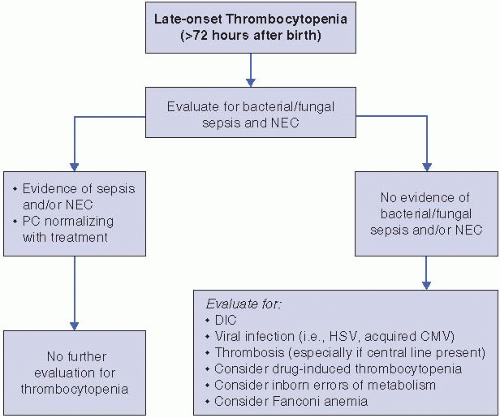

Late-onset thrombocytopenia (Figure 47.2). The most common causes of thrombocytopenia of any severity presenting after 72 hours of life are sepsis (bacterial or fungal) and necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC). Affected infants are usually ill appearing and have other signs suggestive of sepsis and/or NEC. However, thrombocytopenia can be the presenting sign of these processes and can precede clinical deterioration. Appropriate treatment with antibiotics, fluid resuscitation, and bowel rest (if NEC is considered) usually improves the platelet count in 1 to 2 weeks, although in some infants, the thrombocytopenia persists for several weeks. The reasons underlying this prolonged thrombocytopenia are unclear.

If bacterial/fungal sepsis and NEC are ruled out, viral infections such as herpes simplex virus, CMV, or enterovirus should be considered. These are frequently accompanied by abnormal liver enzymes. If the infant has or has recently had a central venous or arterial catheter, thromboses should be part of the differential diagnosis. Finally, drug-induced thrombocytopenia should be considered if the infant is clinically well and is receiving heparin, antibiotics (penicillins, ciprofloxacin, cephalosporins, metronidazole, vancomycin, and rifampin), indomethacin, famotidine, cimetidine, phenobarbital, or phenytoin, among others (13, 14). Other less common causes of late-onset thrombocytopenia include inborn errors of metabolism and Fanconi anemia (rare).

Novel tools to evaluate platelet production and aid in the evaluation of thrombocytopenia have been recently developed and are likely to become widely available to clinicians in the near future. Among those, the immature platelet fraction (IPF) measures the percentage of newly released platelets (<24 hrs). The IPF can be measured in a standard hematologic cell counter (Sysmex XE-2100 hematology analyzer) as part of the complete cell count and can help differentiate thrombocytopenias associated with decreased platelet production from those with increased platelet destruction in a manner similar to the use of reticulocyte counts to evaluate anemia (15). Recent studies have shown the usefulness of the IPF to evaluate mechanisms of thrombocytopenia and to predict platelet recovery in

neonates (16, 17). The IPF should be particularly helpful to guide the diagnostic evaluation of infants with thrombocytopenia of unclear etiology.

III. IMMUNE THROMBOCYTOPENIA.

Immune thrombocytopenia occurs due to the passive transfer of antibodies from the maternal to the fetal circulation. There are two distinctive types of immune mediated thrombocytopenia: (i) neonatal alloimmune thrombocytopenia (NAIT) and (ii) autoimmune thrombocytopenia. In NAIT, the antibody is produced in the mother against a specific human platelet antigen (HPA) present in the fetus but absent in the mother. The antigen is inherited from the father of the fetus. The anti-HPA antibody produced in the maternal serum crosses the placenta and reaches the fetal circulation, leading to platelet destruction and thrombocytopenia. In autoimmune thrombocytopenia, the antibody is directed against an antigen on the mother’s own platelets (autoantibody) as well as on the baby’s platelets. The maternal autoantibody also crosses the placenta, resulting in destruction of fetal platelets and thrombocytopenia.

Neonatal alloimmune thrombocytopenia. NAIT should be considered in any neonate who presents with severe thrombocytopenia at birth or shortly thereafter, particularly in the absence of other risk factors, clinical signs, or abnormalities in the physical exam or in the other blood cell counts. In a study of more than 200 neonates with thrombocytopenia, using a platelet count < 50 × 103/mcL in the first

day of life as a screening indicator identified 90% of the patients with NAIT (18

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree