Neonatal Thrombocytopenia

INTRODUCTION

Thrombocytopenia is a well-recognized phenomenon in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU); it can lead to morbidity and mortality from severe and life-threatening bleeding. The epidemiology, pathophysiology, causes, management, and outcome of neonatal thrombo cytopenia are reviewed in this chapter.

Thrombocytopenia is traditionally defined as a platelet count below 150,000/μL. This definition is based on several population studies, which have demonstrated that in mothers with normal platelet counts, over 98% of healthy term neonates have platelet counts greater than 150,000/μL at birth.1–3 Thrombocytopenia is rare in healthy newborns; however, it affects up to one-third of patients in the NICU.4,5 The increased incidence of thrombocytopenia in NICU patients is reflective of the inverse relationship of thrombocytopenia risk to birth weight and gestational age.4,6 Christensen et al reported that up to 70% of infants with birth weight less than 1000 g are thrombocytopenic.6 Preterm infants, particularly those at less than 24 weeks’ gestation, have platelet counts as low as 100,000/μL in the first few days of life.4,7

Severe thrombocytopenia is defined as a platelet count of less than 50,000/μL. Severe thrombocytopenia occurs in less than 1% of healthy newborns2,3, but affects 5%–10% of hospitalized neonates.4,8,9

CAUSES OF NEONATAL THROMBOCYTOPENIA

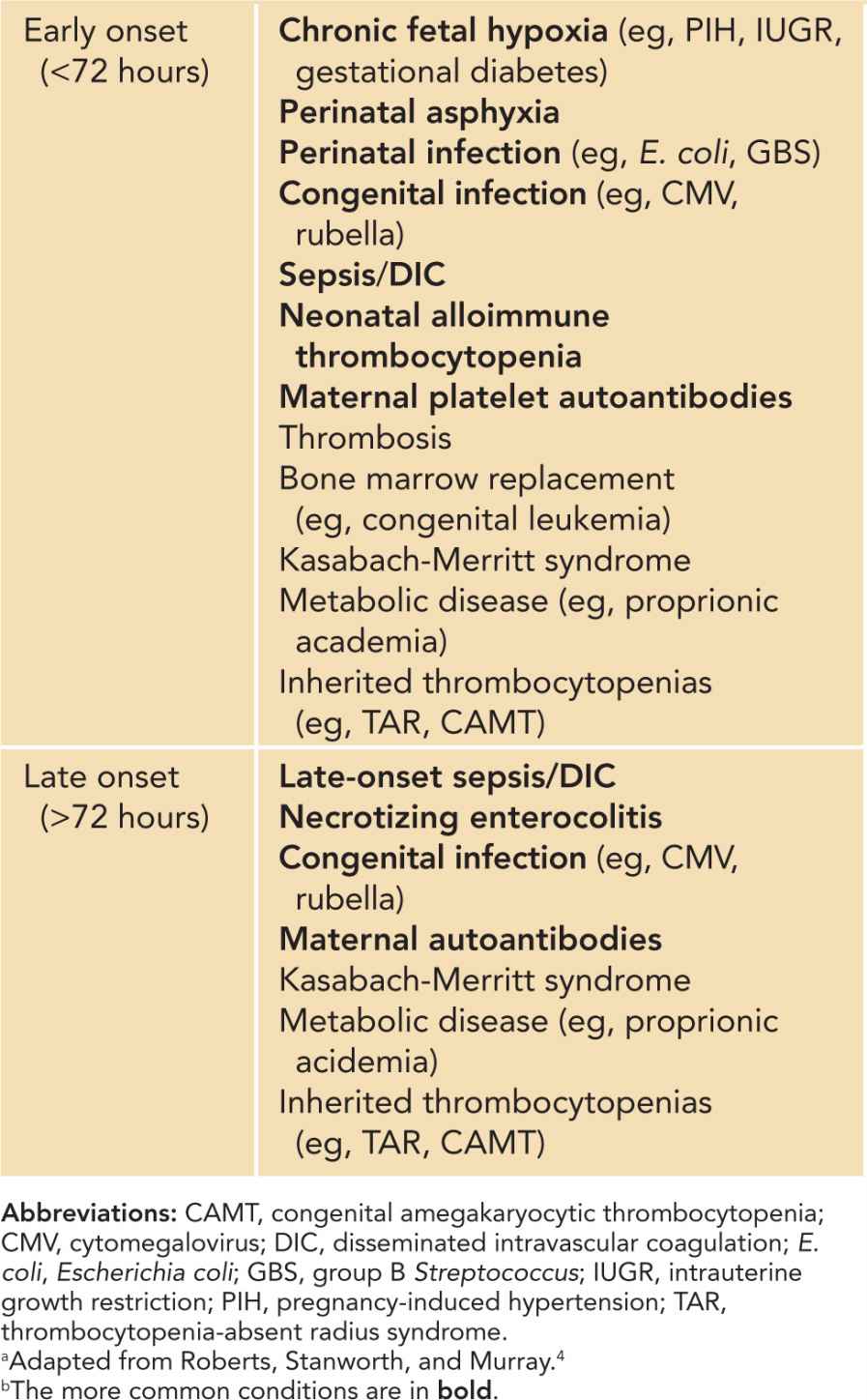

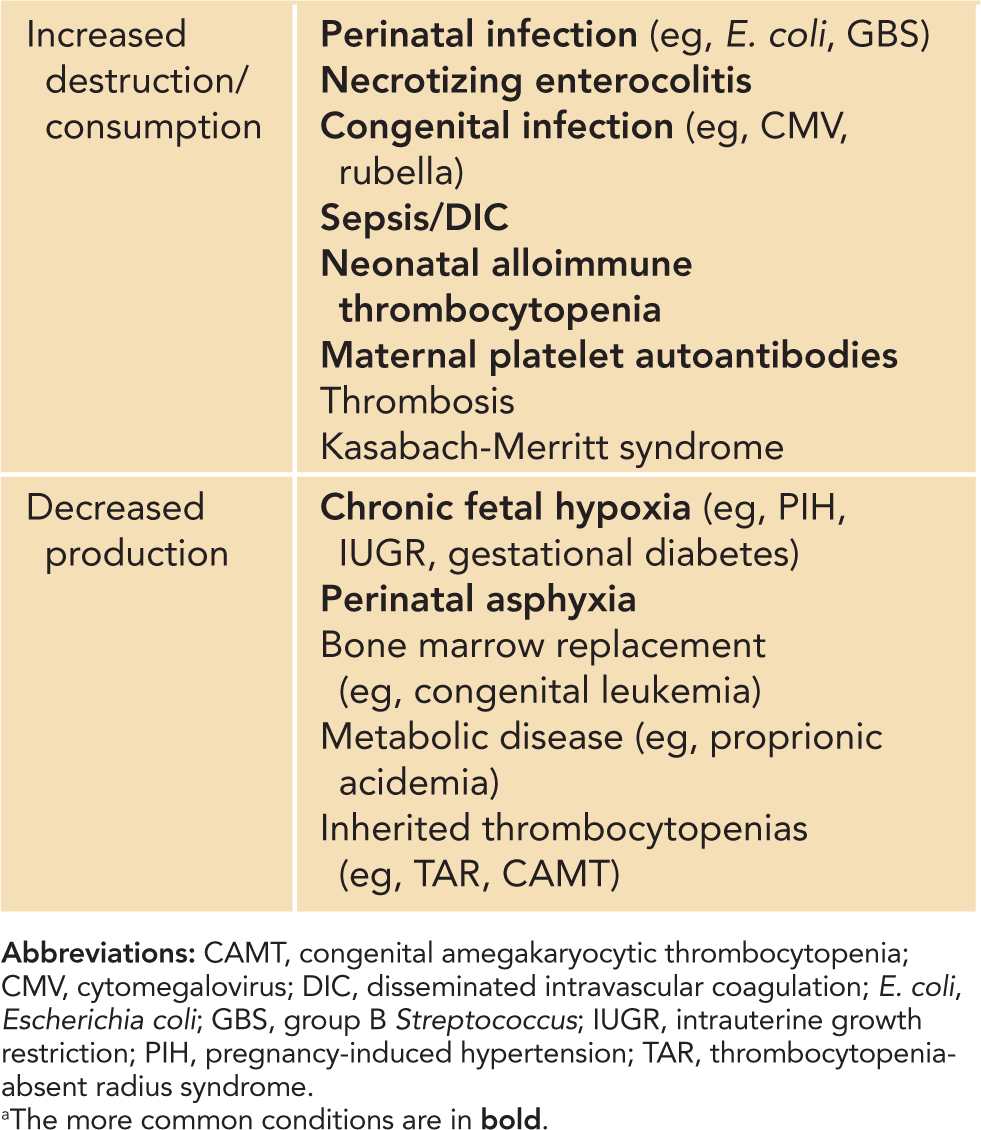

The causes of neonatal thrombocytopenia can be classified into 2 major pathophysiologic categories: increased destruction (including consumption) and decreased production. In some neonates, especially sick preterm infants, both processes can occur concomitantly. The time of thrombocytopenia onset has often been used to help with diagnosis. Early-onset thrombocytopenia occurs within 72 hours of birth, while late-onset thrombocytopenia occurs after 72 hours of life (Table 32-1). Diagnostic algorithms and general management of neonatal thrombocytopenia are highlighted in Chapter 92.

Table 32-1 Classification of Early-Onset (72 Hours Postbirth) Thrombocytopeniasa,b

The diagnoses of thrombocytopenia based on underlying pathophysiologic classifications are summarized in Table 32-2. The most common causes include infection, necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC), neonatal alloimune thrombocytopenia, maternal platelet autoantibodies, and chronic fetal hypoxia. The major causes of neonatal thrombocytopenia are reviewed next.

Table 32-2 Classification of Neonatal Thrombocytopenias by Underlying Pathophysiology: Increased Platelet Destruction and Decreased Platelet Productiona

Congenital Infection

Congenital infections are a major cause of thrombocytopenia in the neonatal population. Cytomegalovirus and herpes simplex virus are the most likely of the congenital TORCH (toxoplasmosis, rubella, cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex virus) infections to cause thrombocytopenia. Cytomegalovirus is the most common of the congenital infections, affecting 0.5%–1.5% of live births. Most of these neonates are asymptomatic, but up to 35% develop thrombocytopenia.10 Other congenital infections that have been implicated include Coxsackievirus, syphilis, varicella zoster virus, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and parvovirus B19.

Mechanisms of thrombocytopenia with congenital infection include increased platelet aggregation, hypersplenism secondary to splenomegaly and platelet pooling, and platelet membrane damage secondary to viral neuraminidase cleavage of sialic acid. Infants with congenital infections are typically well appearing but can present with clinical manifestations such as a petechial rash, microcephaly, intracerebral calcifications, and hepatosplenomegaly. Thrombocytopenia is generally mild to moderate (>50,000/μL), and affected infants usually do not have bleeding apart from cutaneous manifestations. Positive results for a specific congenital infection typically confirm the diagnosis. Most patients do not require therapy for thrombocytopenia, and management generally is close observation. Platelet transfusions may be given for rare cases of severe thrombocytopenia or bleeding.

Bacterial and Fungal Infections

Perinatal bacterial infections particularly implicated in neonatal thrombocytopenia include group B Streptococcus (GBS) and Escherichia coli (E. coli). Other late-onset (>72 hours postdelivery) bacterial and fungal infections may also occur, particularly in vulnerable preterm infants. Mechanisms of thrombocytopenia include endothelial damage and increased platelet aggregation caused by adherence of bacterial products to platelet membranes. Neonates can present with vital sign instability, leukocytosis, and mild-to-severe thrombocytopenia. Sepsis and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) may occur and are associated with rapid onset of severe thrombocytopenia, consumptive coagulopathy, and clinical bleeding or thrombosis. Management includes platelet transfusions for severe thrombocytopenia and bleeding, and most important, aggressive treatment of the underlying infection.

Necrotizing Enterocolitis

Necrotizing enterocolitis occurs in up to 10% of neonates, particularly in those with a birth weight less than 1500 g.11 Platelets are destroyed at sites of gut ischemia, injury, and necrosis, resulting in thrombocytopenia. The degree of thrombocytopenia correlates with gut necrosis severity, particularly within the first 3 days of NEC onset.12 The presence of severe thrombocytopenia may also be predictive of overall morbidity and mortality.12 DIC can also complicate NEC, thereby increasing morbidity and mortality risk from significant bleeding or thrombosis. Platelet transfusions are given for severe thrombocytopenia and clinical bleeding. Thrombocytopenia typically improves with improvement and resolution of the NEC.

Immune-Mediated Thrombocytopenia

There are 2 major immune-mediated causes of neonatal thrombocytopenia: neonatal alloimmune thrombocytopenia (NAIT) and maternal platelet autoantibodies. Immune-mediated neonatal thrombocytopenia most commonly occurs in otherwise-well, term neonates without other reasons for thrombocytopenia. Patients typically have decreased platelet counts at birth (early-onset thrombocytopenia).

Neonatal Alloimmune Thrombocytopenia

Epidemiology

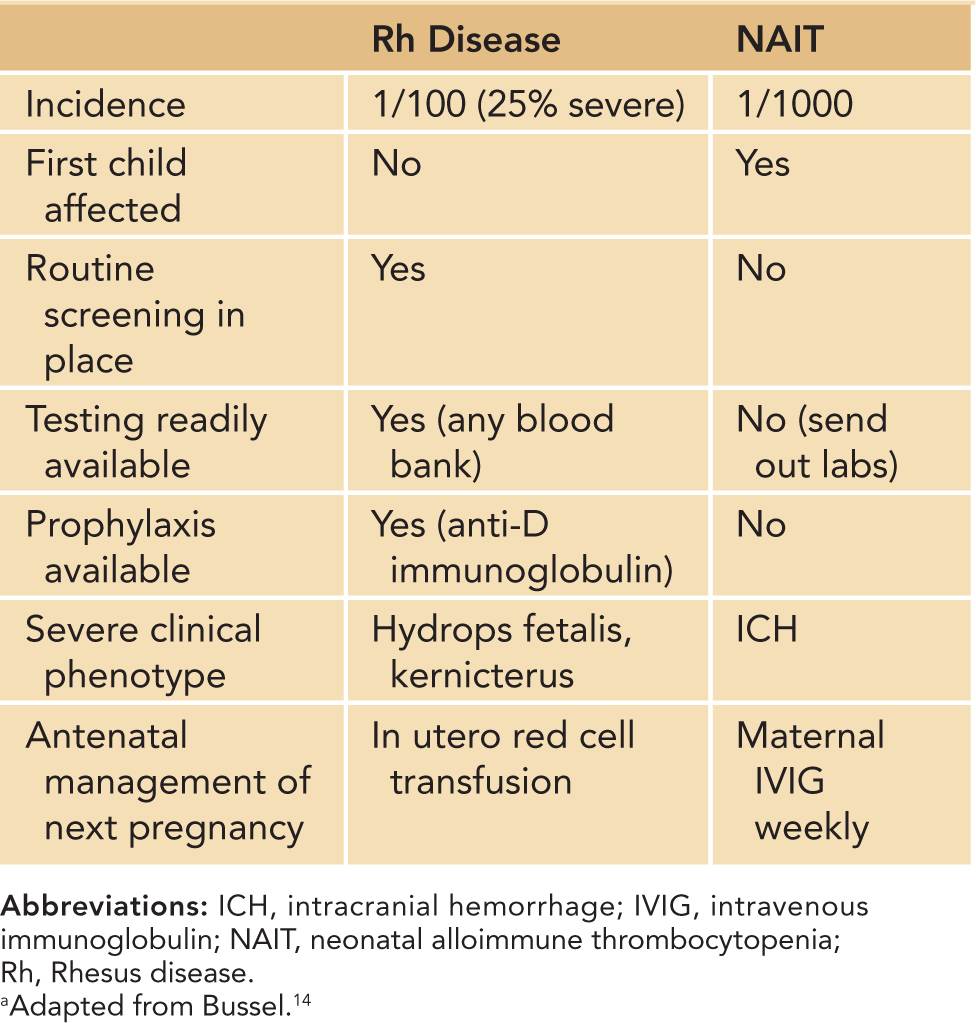

Neonatal alloimmune thrombocytopenia is estimated to occur in 1:1000 live births.13 NAIT is the platelet equivalent of hemolytic disease of the newborn, or Rhesus (Rh) antigen incompatibility. It occurs in the first pregnancy in nearly half of cases, unlike Rh incompatibility, in which neonates are affected only after the index pregnancy.13 Differences between Rh incompatibility and NAIT are outlined in Table 32-3. The majority of patients have severe thrombocytopenia, and often the thrombocytopenia is severe (platelets <20,000/μL).14 Neonates are at high risk of major bleeding, including intracranial hemorrhage (ICH). Large retrospective studies have reported ICH in 10%–20% of untreated NAIT cases.15,16 The bleeding may occur in utero, as thrombocytopenia develops after 20 weeks’ gestation in untreated cases.15,16

Table 32-3 Differences Between Rhesus Disease and Neonatal Alloimmune Thrombocytopeniaa

Pathophysiology

Neonatal alloimmune thrombocytopenia results from transplacental passage of maternal alloantibodies against fetal platelets expressing paternal human platelet antigens (HPAs) that the mother lacks. Sixteen HPA antigens have been identified, and 3 of them cause 95% of NAIT in Caucasians16,17: HPA-1a, HPA-5b, and HPA-15b. HPA-4 has been implicated in NAIT in Asians.16,17 HPA-1a in particular causes nearly 75% of all NAIT cases.16,17 HPA-1a incompatibility occurs in 1:350 pregnancies, but NAIT occurs in only 1:1500 cases.16 The reason for this disparity is due to differences in human leukocyte antigen (HLA) alleles. Specifically, HLA DRB3*0101-positive women are up to 140 times more likely to form HPA-1a antibodies than are HLA DRB3*0101-negative women, thereby indicating a strong association of HLA with NAIT.18,19

Differential Diagnosis

The major and most important differential diagnoses are bacterial and congenital infections. Evaluation for bacteremia with blood counts and cultures is particularly important in the vulnerable neonatal population, and empiric broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy is warranted until bacteremia is excluded. Patients with congenital infections typically have other physical stigmata (see the section on congenital infections), which may aid in diagnosis.

Thrombocytopenia secondary to maternal autoantibodies (see the section on this topic) is an alternative diagnosis that can be excluded by the absence of maternal thrombocytopenia or maternal autoimmune disease (ie, systemic lupus erythmatosus). Thrombocytopenia secondary to hypoxia or acidosis may occur in neonates with complicated pregnancies or deliveries and thus can be excluded in cases of uncomplicated term pregnancies and deliveries. Inherited thrombocytopenia syndromes (see the section on this topic) may also present similarly but are much rarer. The diagnosis of inherited syndromes typically includes evaluation for specific physical examination or peripheral smear findings and genetic testing.

Diagnostic Tests

Thrombocytopenia is evident at birth. Generally, a diagnosis of NAIT requires both evidence of maternal-paternal platelet antigen incompatibility and maternal antiplatelet antibodies. Occasionally, maternal antibodies are found without evidence of platelet antigen incompatibility. In these cases, the reference laboratory should distinguish between “unimportant” antigens (ie, HLA) vs incompatibilities of a previously undefined platelet antigen.14 Evidence of a platelet antigen incompatibility without maternal antibodies is insufficient for an NAIT diagnosis.

Management

Treatment involves platelet transfusions and intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG; 1 g/kg administered over 1–2 days). Historically, recommendations were for transfusion of maternal platelet antigen-matched platelets or HPA-1a-negative platelets if maternal platelet antigen type was unavailable. However, recent studies showed no difference in outcome between antigen-specific and random donor platelets.20,21 Therefore, given the often-lengthy delay in platelet typing or obtaining antigen-specific platelets, recommended initial therapy for NAIT is the administration of IVIG and random donor platelets. The duration of effect of a platelet transfusion needs to be closely monitored to evaluate the need for further transfusion. A head ultrasound should always be performed to evaluate for ICH.

Antenatal management of NAIT has been controversial. Previous recommendations were for fetal platelet monitoring and intrauterine transfusions. However, the invasiveness and complications associated with these procedures have since decreased their appeal. In cases of NAIT in index pregnancies, guidelines for subsequent pregnancies include maternal infusion of IVIG (1 g/kg) weekly, starting at 16 weeks if the previous sibling had ICH and at 32 weeks if not.22 In some protocols, steroids also have been used antenatally in particularly difficult NAIT cases. Because of the intensity of antenatal management, it is important to be certain of NAIT diagnosis.

Outcome and Follow-up

The majority of neonates with thrombocytopenia do well, with the platelets resolving within 7 days after delivery, without relapses or long-term sequelae.15,16 However, a small subset of infants has thrombocytopenia that lasts several weeks and may require additional platelet transfusions. Those neonates who develop ICH have poorer neurodevelopmental outcomes, including cerebral palsy and sensory impairment.16

Maternal Platelet Autoantibodies

Epidemiology

Neonatal thrombocytopenia can also occur in infants born to mothers with platelet autoantibodies. Immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) is the most common underlying disease in mothers, and 10%–15% of maternal ITP cases result in neonatal thrombocytopenia.23 Platelet autoantibodies can also occur in mothers affected with systemic lupus erythematosis (SLE) and hyperthyroidism, among other less-common autoimmune disorders.

Fortunately, neonatal thrombocytopenia associated with maternal autoantibodies is much less of a clinical problem than NAIT. The thrombocytopenia is generally transient, though infants should be closely monitored in the first several days of life, as platelet counts can rapidly drop during this time. The majority of neonates have mild-to-moderate thrombocytopenia (50,000 to 100,000/μL), and most are clinically asymptomatic except for minimal bruising or petechiae.24 However, up to 10% of affected neonates develop more severe thrombocytopenia. ICH is rare and has been reported in less than 1% of infants with severe thrombocytopenia. Predictive factors for clinical bleeding and severe neonatal thrombocytopenia include history of older sibling(s) with severe neonatal thrombocytopenia, maternal platelet count at delivery less than 100,000/μL, and maternal ITP refractory to splenectomy.23

Pathophysiology

Neonatal thrombocytopenia occurs secondary to maternal antiplatelet autoantibodies that cross the placenta to also affect the fetus and newborn. Autoantibodies are typically directed against platelet glycoprotein (Gp) IIbIIIa, although there are also cases of anti-Gp1b autoantibodies.

Differential Diagnosis

Maternal ITP should not be confused with gestational thrombocytopenia, a benign transient entity that occurs in women only during pregnancy and resolves spontaneously after delivery. Affected women are typically healthy, have no history of autoimmune disease, and have an uncomplicated pregnancy. Maternal platelet counts are mildly low in the majority of cases. Furthermore, neonatal thrombocytopenia rarely occurs. Both mothers and fetuses typically are asymptomatic and do not require any medical treatment.

Other major differential diagnoses include bacterial and congenital infections. Bacterial infections should be strongly considered and empirically treated until cultures are proven negative, particularly in high-risk neonates. NAIT may be excluded by the presence of maternal thrombocytopenia or maternal autoimmune disease. Inherited thrombocytopenia syndromes are alternative diagnoses that are typically associated with distinct physical examination or peripheral smear findings and are often diagnosed with specific genetic testing.

Diagnostic Tests

There is no specific test for thrombocytopenia secondary to maternal autoantibodies. Tests for anti-GpIIbIIIa or anti-Gp1b antibodies have low sensitivity. Instead, diagnosis is typically based on maternal and neonatal history and other laboratory findings. The greatest diagnostic clue is a maternal history of ITP or other autoimmune disorder. Affected mothers and neonates typically have isolated thrombocytopenia and variably large platelets on peripheral smear, typical of what is seen with ITP. Thrombocytopenia in the neonate is evident at birth. Mothers may also have a previous history of ITP treatment, including steroids, IVIG, and splenectomy. Previously splenectomized mothers actually may have a normal platelet count but still have circulating autoantibodies that can cross the placenta to destroy fetal platelets. Therefore, if maternal platelet counts are normal but maternal autoantibodies are suspected, it is important to query mothers regarding whether they previously had their spleen removed or if they have any other history of autoimmune disease.

Management

Treatment of thrombocytopenia is typically supportive. In the presence of severe thrombocytopenia or life-threatening bleeding, first-line therapy includes IVIG (1 g/kg administered over 1–2 days). Platelet transfusions also may be indicated, although since maternal antibodies are directed against common antigens, the transfusion may not be effective.

Previously, the antenatal management of known maternal ITP cases included removing the mother’s spleen and fetal blood sampling to determine the safety of vaginal delivery. However, current recommendations are less invasive, with IVIG or steroids for the mother to delay splenectomy until at least after delivery. Fetal blood sampling is no longer done. Furthermore, cesarean sections now are recommended only for obstetric indications.

Outcome and Follow-up

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree