Neonatal Mortality and Morbidity

Avroy A. Fanaroff

Infant mortality is an important outcome measure of the health services of a population. In the United States, where there are approximately 4 million births each year, the infant mortality is around 7 per 1000 live births. The highest risk of infant death is within 24 hours of birth, but mortality and morbidity remain high during the neonatal period, from birth to the 28th day of life. In the United States each year, nearly 1% of pregnancies are complicated by fetal death and about 0.5% by neonatal mortality.1-8 The fetus and newborn are most vulnerable during labor, delivery, and the neonatal period because central nervous system injury may result in lifelong morbidity and neurodevelopmental impairment. The perinatal period, from 28 weeks of gestation to the 28th day of life, is the period of greatest mortality. In the modern era, with survival of extremely-low-birth-weight infants, postneonatal mortality also contributes significantly to the infant mortality rate.

DEFINITIONS

The reduction of maternal and infant mortality and the improvement of the health of mothers and infants in the United States are high priorities. Statistical comparisons among countries, states, regions, and individual centers have been hampered by differences in definitions. In order to compare outcomes and plan interventions, it is imperative that standard definitions be utilized9:

Appropriate for gestational age (AGA): An infant with a birth weight between the 10th and 90th percentiles for that gestational age. Those below the 10th percentile are regarded as small for gestational age (SGA), whereas those above the 90th percentile are considered large for gestational age (LGA).

Birth weight: The weight of a neonate determined immediately after delivery or as soon thereafter as feasible, expressed to the nearest gram.

Fetal death: Death before the complete expulsion or extraction from the mother of a product of human conception, fetus and placenta, irrespective of the duration of pregnancy; the death is indicated by the fact that after such expulsion or extraction, the fetus does not breathe or show any other evidence of life, such as beating of the heart, pulsation of the umbilical cord, or definite movement of voluntary muscles. Heartbeats are to be distinguished from transient cardiac contractions; respirations are to be distinguished from fleeting respiratory efforts or gasps. This definition excludes induced termination of pregnancy.

Gestational age: The number of weeks that have elapsed between the first day of the last normal menstrual period (not the presumed time of conception) and the date of delivery, irrespective of whether the gestation results in a live birth or a fetal death.

Infant death: Any death at any time from birth up to, but not including, 1 year of age.

Live birth: The complete expulsion or extraction from the mother of a product of human conception, irrespective of the duration of pregnancy, which, after such expulsion or extraction, breathes or shows any other evidence of life, such as beating of the heart, pulsation of the umbilical cord, or definite movement of voluntary muscles, whether or not the umbilical cord has been cut or the placenta is attached. Heartbeats are to be distinguished from transient cardiac contractions; respirations are to be distinguished from fleeting respiratory efforts or gasps.

Low birth weight: Any neonate, regardless of gestational age, whose weight at birth is less than 2500 g.

Neonatal death: Death of a liveborn neonate before the neonate becomes 28 days old.

Perinatal death: Death from the 28th week of gestation to the 28th day of life. Perinatal mortality measures should be based on specific weight rather than gestational age, and indices of perinatal mortality combine fetal deaths and live births with only brief survival (up to a few days or weeks) on the assumption that similar factors are associated with these losses.

Postterm: Any neonate whose birth occurs from the beginning of the first day (295th day) of the 43rd week following the onset of the last menstrual period.

Preterm: Any neonate whose birth occurs through the end of the last day of the 37th week (259th day) following the onset of the last menstrual period.

Term: Any neonate whose birth occurs from the beginning of the first day (260th day) of the 38th week through the end of the last day of the 42nd week (294th day) following the onset of the last menstrual period.

REGIONALIZATION

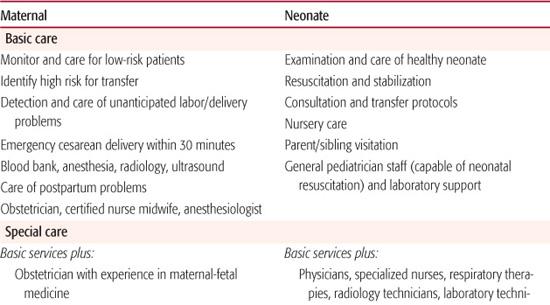

Regionalization of perinatal care to various levels (see Table 41-1), first introduced in the 1970s, was cost effective and reduced morbidity and mortality. Market forces and economics disrupted regionalization in the 1990s. Nonetheless, the evidence continues to demonstrate that the best outcomes for low-birth-weight infants are achieved when they are delivered at the larger subspecialty centers (formerly known as level III), those with an average neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) daily census in excess of 15. There has been a large increase in both the number of NICUs in community hospitals and the complexity of the cases treated in these units. The mortality among very-low-birth-weight infants was lowest for deliveries that occurred in hospitals with NICUs that had both a high level of care and a high volume of such patients, implying that increased use of such facilities might reduce mortality among very-low-birth-weight infants. Risk-adjusted neonatal mortality for infants born in smaller level III NICUs and in level II+ and level II NICUs (specialty), regardless of size, was not significantly different from that in hospitals without a NICU and was significantly higher than in hospitals with large subspecialty NICUs.10,11

Despite the differences in outcomes, costs for the birth of infants born at hospitals with large subspecialty NICUs were not more than those for infants born at other hospitals with NICUs. Concentration of high-risk subspecialty NICU care has the potential to decrease neonatal mortality without increasing costs.

NEONATAL MORTALITY

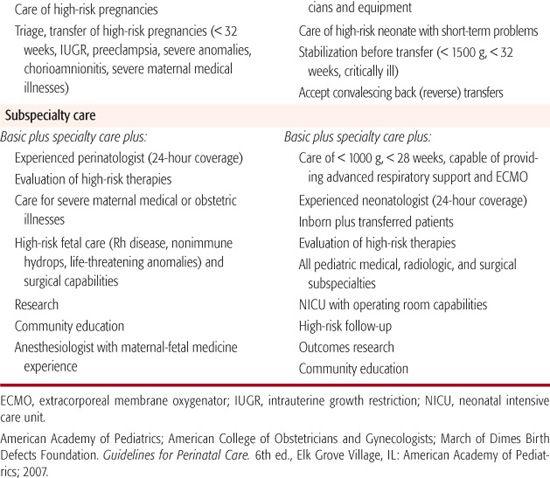

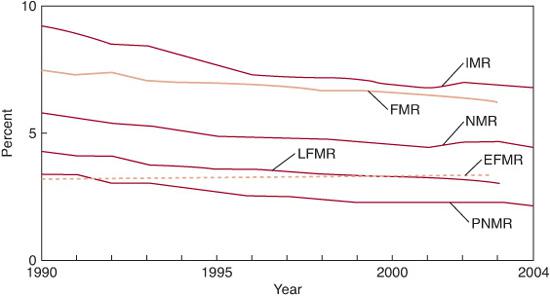

Infant and neonatal mortality rates are presented in Figure 41-1. Advances in perinatal care have improved the chances for survival of infants with major congenital anomalies in addition to those with cardiorespiratory disorders and other major organ system failures. The outlook for extremely-low-birth-weight and lowgestational-age infants has also improved remarkably.12,13 Many factors influence neonatal mortality. In addition to race, birth weight, gestational age, gender, place of delivery, and intrauterine growth, there are wide variations in population descriptions, in the criteria used for starting or withdrawing treatment, in the reported duration of survival, and in care. The perinatal mortality rate in the United States has consistently declined with an overall decrease of 10% from 1990 to 2003. In 2002 to 2003, the perinatal mortality rate reached its nadir of 6.74 deaths per 1000 live births and fetal deaths. The recent decline is attributable to a drop in late fetal deaths. In 2004, the US fetal mortality rate was 6.20 fetal deaths of 20 weeks of gestation or more per 1000 live births, and fetal deaths were greatest in teenagers, mothers over age 35, and those with multiple fetuses. Race played a major role, and the rate in non-Hispanic black women (11.25 per 1000) far exceeded non-Hispanic white women (4.98 per 1000).

Table 41-1. Levels of In-Hospital Perinatal Care

Fetal and perinatal mortality rates have declined slowly but steadily from 1990 to 2004. Fetal mortality rates for 28 weeks of gestation or more have declined substantially, whereas those for 20 to 27 weeks of gestation have not declined. In 2004, one half of fetal deaths of 20 weeks of gestation or more occurred between 20 and 27 weeks of gestation.6

Hamilton7,8 noted that the neonatal mortality rate had declined steadily until 2001 to 2002, when it increased from 4.5 to 4.7 deaths per 1000 live births. This increase was primarily driven by the birth rate of infants with birth weights below 750 grams and particularly by those with weights below 500 grams aided and abetted by assisted reproduction techniques, which increased the number of multiple births, premature deliveries, and extremely-low-birth-weight infants. In 2004, the neonatal mortality rate declined back to 4.52 per 1000 live births.4

RACE

RACE

Factors that increase mortality rates several fold include prematurity, no prenatal care, inadequate weight gain in pregnancy, African American ethnicity, and inadequate prenatal care. The importance of race as a determinant of neonatal mortality is shown by the 1997 mortality rates in the United States for infants born to Asian and Pacific Islander mothers (5:1000 live births) followed by white (6.0), American Indian (8.7), and black (13.7) mothers. African American women have many more preterm and very early preterm births, which, in part, explain the doubling of their fetal and infant mortality rates. In general, however, the racial discrepancies in preterm birth and other pregnancy outcomes remain unexplained. Although there has been a noticeable decline in the perinatal mortality rates for the past few decades, the prematurity rate has remained fairly constant, and African American infants continue to have a higher mortality rate than their white counterparts. The relative differences in perinatal and neonatal mortality between different racial/ethnic populations have not substantially changed. Non-Hispanic black newborns, with an infant mortality rate (IMR) of 13.6 per 1000 live births, are twice as likely as non-Hispanic white (IMR 5.7:1000) and Hispanic-black infants (IMR 5.65:1000) to die within the first year of life. Although for the total birth cohort, blacks have a higher mortality risk than whites, the reverse is noted at the lower weight group/gestational age distributions.

MATERNAL FACTORS

MATERNAL FACTORS

Infant mortality rates are higher for pregnancies in which prenatal care is initiated after the first trimester of pregnancy and in infants born to teenagers or to women 40 years of age or older who did not complete high school, were unmarried, or smoked during pregnancy. Infant mortality is also higher for male infants, multiple births, and infants born preterm or at low birth weight. In many instances, the precipitating cause of preterm delivery remains undetected, but risk factors for premature birth include uterine abnormalities, placental bleeding including abruptio placenta associated with cocaine use, maternal chronic illnesses, multifetal gestation, premature rupture of the membranes, chorioamnionitis, and bacterial vaginosis. Bacterial vaginosis, a short cervix, and the presence of fetal fibronectin in the vaginal tract are predictors of preterm delivery, but treatment of the bacterial vaginosis has been ineffective in preventing prematurity. Premature delivery complicates over 10% of births but contributes disproportionately to at least two thirds of the infant deaths and to a significant amount of neonatal and long-term morbidity, which may include cerebral palsy, mental restriction, physical handicap, blindness, and deafness in addition to major and minor school adaptive and learning problems.14-16 Although there has been a substantial decline in the number of medically preventable deaths and deaths from respiratory distress syndrome, the number of deaths from extremely low birth weight has increased relative to other causes; asphyxia, birth trauma, early-onset sepsis, and meconium aspiration syndrome have been reduced to a minimum. Nonetheless, congenital malformation is the leading cause of infant death in the United States and accounts for a much greater proportion of infant mortality than does premature birth. To further reduce neonatal mortality, the incidence of lethal congenital malformations and very-low-birth-weight infants must be addressed; congenital anomalies cause approximately 23% of infant mortality, and short gestation and low birth weight, about 15%.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree