Musculoskeletal Pain Syndromes

Yukiko Kimura

With a prevalence as high as 15%, chronic pain is increasingly being recognized as a common problem in children and adolescents,1 but one that is still poorly understood. This chapter describes evolving concepts of several syndromes in which musculoskeletal pain is a prominent feature. Interestingly, these pain syndromes frequently have overlapping features. However, most children can be readily diagnosed by the typical pattern of somatic complaints and the salient physical findings specific to each syndrome.

GROWING PAINS

Growing pains occur in children between the ages of 3 and 12, and are characterized by intermittent nighttime nonarticular aching or pain most commonly in the legs. Recent prevalence estimates vary from less than 3%2 to as many as 36.9% in 4 to 6 year olds in Australia.3 An extension of the syndrome in adolescents and adults may include restless legs syndrome. In one recent population study, the prevalence of restless legs syndrome was found to be 1.9% in 8 to 11 year olds and 2% in 12 to 17 year olds; a history of growing pains and sleep disturbances was more common in the study population.4 Interestingly, restless legs syndrome also is reported to be common in patients with fibromyalgia, another pain syndrome which is described later in this chapter.5 The pathogenesis of growing pains is unknown. Despite the name, it is almost certainly not owing to growing.6 Perhaps this term is used because the condition occurs in children (who are always growing), and does not occur in adulthood (after cessation of growth). Recently, investigators have shown that children with growing pains may have increased pain sensitivity11 and decreased bone strength as measured by quantitative ultrasound.12

Growing pains are typically bilateral, usually occurring in the evening or at night, and not associated with limping or limited mobility. There is no history of trauma or infection, and objective findings are lacking on physical examination. The areas most frequently involved include the thighs, calves, and, occasionally, the forearms and trunk.

Parents of children with growing pains report no swelling, color changes, or warmth of the affected limb. The physical examination is unrevealing. X-rays and laboratory tests may be necessary to alleviate parental concern,13 but if the clinical picture is typical, they are not necessary. In contrast to patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA), who usually have more pain and stiffness when first arising in the morning, these children are usually asymptomatic in the morning.

If the child has a limp, is complaining of pain in or around the joint, or has an abnormal musculoskeletal exam, growing pains is probably not the correct diagnosis. A thorough investigation for known causes of joint pain should be pursued, such as infection, inflammatory arthritis, and neoplasm, as well as orthopedic and endocrine disorders.

Treatment for this condition is symptomatic. Heat, massage, and analgesics such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents or acetaminophen, have all been suggested, but none have been tested in a prospective fashion. Reassurance that growing pains have no long-term sequelae and represent a relatively benign condition is important.

HYPERMOBILITY SYNDROMES

Hypermobility is widely prevalent in children and adolescents, and may be responsible for a wide variety of musculoskeletal complaints including benign joint hypermobility syndrome (BJHS), patellar subluxation, articular dislocation, premature osteoarthritis, and increased susceptibility to ligamentous injury. In addition to causing joint specific problems, BJHS is also now known to be associated with chronic pain, fatigue, and possibly dysautonomia in adults.14 Additional hereditary diseases that must be considered in the differential diagnosis of joint laxity include: (1) Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, (2) Marfan syndrome, (3) marfanoid hypermobility syndrome, (4) osteogenesis imperfecta, (5) Williams syndrome, and (6) inborn errors of metabolism such as homocystinuria and hyperlysinemia.

There is tremendous variability in the reported prevalence of joint hypermobility in the general population, with studies reporting incidences from as low as 2% to as high as 30%. Hypermobility appears to be more common in younger children and in females.15-18 There may be racial and ethnic differences as well. Estimates of the prevalence of hypermobility in children vary from 10% to 34%, declining during the school-aged years.19,20 The prevalence of pain in adults with BJHS varies between 5 to 45% depending upon the group studied.21,22 Children affected by BJHS are usually school-aged and adolescents, although patients under age 5 have been described. An increased incidence of a familial tendency for joint hypermobility has been reported. The parents may report that they were loose-jointed as youngsters.

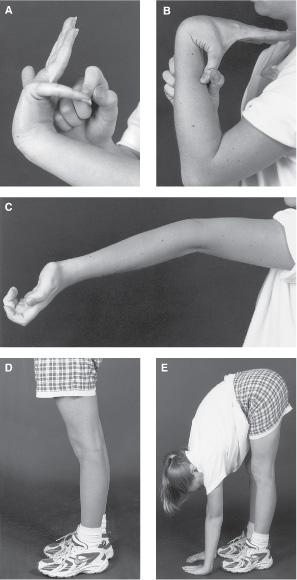

FIGURE 207-1. Demonstrations of Beighton score components. (A) Extension of the wrist and metacarpophalangeal joints so that the fingers are parallel to the dorsum of the forearm. (B) Passive apposition of the thumb to the flexor aspect of the forearm. (C) Hyperextension of the elbows 10 degrees or more. (D) Hyperextension of the knees 10 degrees or more. (E) Flexion of the trunk with the knees fully extended so the palms rest on the floor.

DIAGNOSIS

DIAGNOSIS

The 1998 Revised Brighton Criteria23 are the most recently published criteria for hypermobility. The components of the Beighton score consist of five simple maneuvers: (1) extension of the wrist and metacarpophalangeal joints so that the fingers are parallel to the dorsum of the forearm; (2) passive apposition of the thumb to the flexor aspect of the forearm; (3) hyperextension of the elbows 10 degrees or more; (4) hyperextension of the knees 10 degrees or more; and (5) flexion of the trunk with the knees fully extended so the palms rest on the floor (Fig. 207-1). Patients are scored on a 9-point scale, with one point awarded for each hypermobile site. A Beighton score of 4 or more points fulfills criteria for hypermobility. However, the use of the Beighton score to diagnose hypermobility in children may not be optimal: since children are more hypermobile than adults, it may identify as many as 50% of children as being “abnormal” in terms of excessive hypermobility.

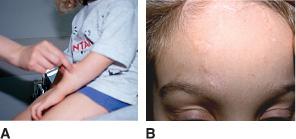

The other criterion for the diagnosis of BJHS are shown in Table 207-1. The examiner should also look for stigmata of heritable connective tissue diseases such as Marfan syndrome (Marfanoid habitus, arachnodactyly, high-arched palate, ocular abnormalities such as drooping eyelids and dislocated lens), and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome including increased elasticity of the skin, abnormal “papyraceous” scars, and a velvety texture of the skin (see Fig. 207-2).

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

The symptoms attributed to BJHS include joint and muscle pain, transient joint swelling, and subjective stiffness; these are typically worsened with increased physical activity. The joints most commonly involved are the lower extremity joints, but the back also may be affected. If joint swelling is present, consideration must be given to an inflammatory arthropathy such as juvenile idiopathic arthritis. A high frequency of hypermobility was found in a group of children with recurrent episodes of joint pain that was called juvenile episodic arthritis/arthralgia.24 These children most likely simply have hypermobility syndrome, with the swelling likely owing to edema from strain and sprain injuries rather than true joint effusions.

Table 207-1 1998 Revised Brighton Criteria for Benign Joint Hypermobility Syndrome

Major Criteria |

1. A Beighton score of 4 out of 9 or greater (either currently or historically) |

2. Arthralgia for longer than 3 months in four or more joints |

Minor Criteria |

1. A Beighton score of 1, 2, or 3 out of 9 |

2. Arthralgia (≥3 months) in one to three joints or back pain (≥3 months), spondylosis, spondylolysis/spondylolisthesis |

3. Dislocation/subluxation in more than one joint, or in one joint on more than one occasion |

4. Soft tissue rheumatism, at least lesions (eg, epicondylitis, tenosynovitis, bursitis) |

5. Marfanoid habitus (tall, slim, span/height ratio <1.03, upper: lower segment ratio less than 0.89, arachnodactyly (positive Steinberg/wrist signs) |

6. Abnormal skin: striae, hyperextensibility, thin skin, papyraceous scarring |

7. Eye signs: drooping eyelids or myopia or anti-mongoloid slant |

8. Varicose veins or hernia or uterine/rectal prolapse |

Pes planus, which becomes apparent on weight bearing, is also common in hypermobility and may cause musculoskeletal pain that tends to improve with the use of orthotics. Chronic nonspecific back pain may also be secondary to hypermobility, and can also predispose to injuries such as spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree