Melanocytic Lesions and Disorders of Pigmentation

Julie V. Schaffer and Seth J. Orlow

Melanocytic lesions are extremely common in pediatric patients. At least 1 melanocytic nevus develops by early childhood in more than 95% of fair-skinned individuals.1 Dermal melanocytosis and other pigmented lesions such as freckles, lentigines, café au lait macules, and Becker nevi are also frequently observed in children and adolescents. In addition, a variety of disorders characterized by increased or decreased cutaneous pigmentation can present in childhood, ranging from postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and hypopigmentation to vitiligo to patterned pigmentation reflecting cutaneous mosaicism. Genetic diseases with pigmentary manifestations (eg, oculocutaneous albinism, piebaldism, Waardenburg syndrome, tuberous sclerosis, neurofibromatosis) are reviewed in Chapter 360. It is important for pediatricians to be aware of the clinical spectrum and natural history of benign melanocytic lesions and self-limited disorders of pigmentation in children as well as of findings that should raise concern.

MELANOCYTIC NEVI AND OTHER PIGMENTED LESIONS

Melanocytic nevi (moles) are benign proliferations of nevus cells, a type of melanocyte that clusters in nests and (with the exception of blue nevi) lacks dendrites. Melanocytic nevi can be acquired or congenital, banal or atypical (dysplastic). There are several variants, such as halo, blue, and Spitz nevi, that have specific clinical and histologic characteristics.2

ACQUIRED MELANOCYTIC NEVI

ACQUIRED MELANOCYTIC NEVI

Acquired melanocytic nevi begin to appear after the first 6 months of life and increase in number during childhood and adolescence, typically reaching a peak count during the third decade and then slowly regressing with age.3-5 Both environmental and genetic factors play a role in the development of acquired melanocytic nevi. Sun exposure (especially when intense and intermittent, eg, while on vacation) is the primary environmental influence (eTable 361.1  ); hereditary components include pigmentary phenotype as well as a particular predisposition to “moliness.”

); hereditary components include pigmentary phenotype as well as a particular predisposition to “moliness.”

Sun exposure during childhood, especially when intense and intermittent, has a major influence on the number and location of nevi as well as the risk of melanoma during adulthood.6 Sunscreen use can be protective against nevus development if combined with a sensible approach to sun exposure.1

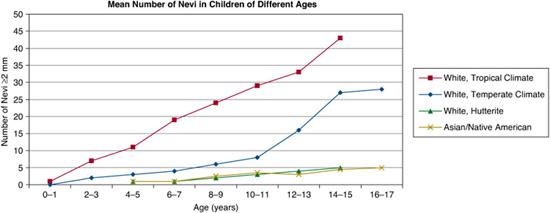

FIGURE 361-1. Mean numbers of nevi in children of different ages. (Source: Adapted from Schaffer JV. Pigmented lesions in children: when to worry. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2007;19(4):430-440.)

In general, individuals with lightly pigmented skin have more nevi than those with darker complexions.1,3,4,9,10 The mean number of nevi in white adolescents is approximately 15 to 25 (with higher numbers in those living in tropical climates), compared to 5 or fewer in adolescents of African, Asian, or Native American heritage (Fig. 361-1). However, individuals with the fairest skin, especially when accompanied by red hair (the “red hair phenotype”), also tend to have fewer nevi.1,3,9,10

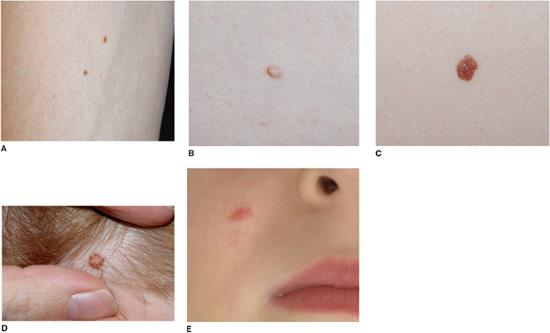

The names applied to acquired nevi reflect the location of the nests of melanocytes. Nests are at the dermal-epidermal junction in junctional nevi, in the dermis in intradermal nevi, and at both sites in compound nevi. Clinically, with progressive migration of melanocytes from the dermal-epidermal junction into the dermis, nevi become more elevated and less pigmented (Fig. 361-2A–D). Although banal (common) acquired nevi have a wide range of clinical appearances (ranging from a dark brown macule to a tan pedunculated papule), they tend to be less than 6 mm in diameter and symmetric, with a homogenous surface, even pigmentation, round or oval shape, regular outline, and sharply demarcated border. Close inspection sometimes reveals pigmentary stippling or perifollicular hypopigmentation.

ATYPICAL (DYSPLASTIC) MELANOCYTIC NEVI

ATYPICAL (DYSPLASTIC) MELANOCYTIC NEVI

Atypical nevi are acquired melanocytic nevi that share, usually to a lesser degree, some of the clinical features of melanoma but are benign. For example, the color of atypical nevi is often variegated (eg, containing pink, tan, brown, and dark brown hues), and the borders are characteristically ill defined (“smudged”) and may be irregular. Considerable controversy has surrounded terms such as dysplastic nevus, and the 1992 Nation Institutes of Health Consensus Conference recommended the use of the more clinically descriptive term atypical nevus. They also recommended that the lesions be described histologically as “nevi with architectural disorder,” with specification of the degree of melanocytic atypia present (none, mild, moderate, or severe).12 Of note, clinical and histologic atypia in melanocytic nevi are not highly correlated.

FIGURE 361-2. Acquired melanocytic nevi. Banal junctional (A), compound (B), and intradermal (C) nevi presenting as a dark brown macule, a medium brown papule, and a soft tan papule respectively. Nevi on the scalp of children often have a tan center and stellate brown rim (D), and Spitz nevi classically appear as a uniformly pink papule on the cheek (E).

Atypical nevi usually begin to appear around puberty and continue to develop throughout life.13 Their density is greater on areas of the body that receive intermittent sun exposure than in non-sun-exposed sites such as the buttocks. The prevalence of clinically atypical nevi in white populations is approximately 2% to 10%, and their presence is best predicted by an increased total number of acquired nevi. The tendency to develop atypical nevi has a genetic basis, and the diagnosis of atypical mole syndrome has been applied to individuals with multiple atypical nevi, especially in the setting of a personal or family history of melanoma.12

Although themselves benign, multiple atypical nevi represent a marker of patients with an increased risk of melanoma and thus in need of periodic total body skin examinations. Compared to the general population, patients with atypical nevi tend to develop melanomas at an earlier age; the relative risk varies from 2-fold to 8-fold in those with no personal or family history of melanoma to more than 100 in those with 2 or more family members with melanoma.13

Halo Nevi

The halo nevus is a melanocytic nevus surrounded by a round or oval halo of depigmentation, which is usually (but not always) symmetric (see Fig. 361-3C).16 This pigment loss often heralds spontaneous regression of the central nevus via a process involving an immune response to nevus antigens. Halo nevi occur in approximately 5% of white children 6 to 15 years of age, with a higher incidence in patients with an increased number of nevi and a personal or family history of vitiligo. The back is the most common location for halo nevi, and half of patients have multiple lesions.  A biopsy of the central nevus can be performed if it has worrisome features, but biopsy is usually not required.

A biopsy of the central nevus can be performed if it has worrisome features, but biopsy is usually not required.

Blue Nevi

Blue nevi represent benign proliferations of dendritic dermal melanocytes that produce melanin. Sites of predilection of blue nevi (head, neck, dorsal aspects of the distal extremities, sacral area) represent locations where active dermal melanocytes are normally still present at birth.

Several variants of blue nevi have been described.18 The common blue nevus typically presents as a solitary, uniformly blue to blue-black papule that measures less than 1 cm in diameter. These nevi frequently arise in adolescence and are most often found on the face or dorsal surfaces of the hands and feet. The cellular blue nevus tends to be a larger nodule or plaque, measuring 1 cm or more in diameter, with a smooth or mammillated surface. Cellular blue nevi can be congenital or acquired and are most often located on the scalp or buttocks. If multiple blue nevi are present (particularly epithelioid blue nevi, a form of pigmented epithelioid melanocytoma), the Carney complex of myxomas (mucocutaneous and cardiac), spotty pigmentation (lentigines as well as blue nevi), and endocrine neoplasia should be considered.19

Stable blue nevi require no intervention, although small lesions that grow rapidly should be biopsied. Surgical excision can be considered for cellular blue nevi that are difficult to follow due to location or topography. Malignant blue nevi (a type of melanoma) have been reported, especially within cellular blue nevi located on the scalp.

Spitz Nevi (Spindle-Cell and Epithelioid-Cell Nevi)

Spitz nevi are benign, usually acquired proliferations of melanocytes with histopathologic features that sometimes overlap with those of melanoma. Most Spitz nevi appear during childhood, often with a rapid initial growth phase. The face and lower extremities represent the most common locations. Lesions classically appear as uniformly pink (Fig. 361-2E), tan, red or red-brown, solitary, dome-shaped papules. They are usually symmetric, well-circumscribed, and less than 1 cm in diameter. The surface may be smooth or verrucous; darkly pigmented lesions are occasionally observed.

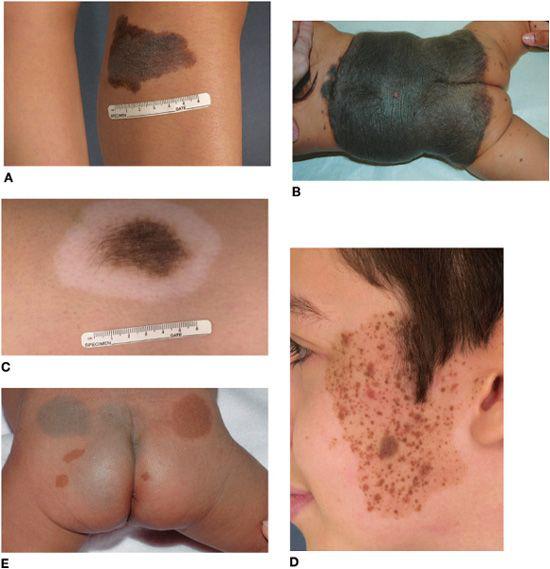

FIGURE 361-3. Pigmented birthmarks. A: Medium-sized congenital melanocytic nevus with an irregular border and pebbly surface. B: Large congenital melanocytic nevus in a partial bathing trunk distribution with satellite nevi. C: Halo congenital melanocytic nevus undergoing spontaneous regression. D: Speckled lentiginous nevus with brown to red-brown papules of various sizes superimposed upon a tan background patch. Hypertrichosis is evident in B, C, and (within some of the papules) D. E: Mongolian spots and café au lait macules on the buttocks, with the latter representing a sign of this infant’s neurofibromatosis. Note the ring of sparing from dermal melanocytosis surrounding the café au lait macules.

A presumed Spitz nevus with atypical clinical features (eg, diameter > 1 cm, asymmetry, or ulceration) should be biopsied with a goal of completely, yet conservatively, removing the lesion. Clinical monitoring represents an option for children with small, stable, clinically classic Spitz nevi.22 If the margins of a biopsy specimen are positive but a histologic diagnosis of classic Spitz nevus can be established with certainty, reexcision to ensure complete removal may not be necessary.23 However, lesions with unusual histologic features need to be excised in their entirety. Occasionally, unequivocal histologic distinction of atypical Spitz tumors from melanoma is not possible.24

ACRAL NEVI

ACRAL NEVI

Children with darkly pigmented skin have a relative predisposition to develop nevi on the palms and soles, which is not related to sun exposure.25 These nevi are usually flat or slightly elevated and brown to dark brown in color, exhibiting linear streaks of darker pigmentation along the prominent skin markings.

Nevi that involve the nail matrix can present as longitudinal melanonychia, a tan, brown or black streak caused by increased melanin deposition in the nail plate. In darkly pigmented individuals, longitudinal melanonychia is commonly seen on multiple nails due to increased melanin production by normal matrix melanocytes. Although streaks that develop in childhood are usually benign,26 single bands that are dark in color or wide (≥ 6 mm), become darker or wider with time, are associated with nail dystrophy, or have extension of pigmentation beyond the nail fold warrant consideration of biopsy of the nail matrix to exclude melanoma.

CONGENITAL MELANOCYTIC NEVI

CONGENITAL MELANOCYTIC NEVI

Congenital melanocytic nevi (CMN) are classically defined as melanocytic nevi present at birth or within the first few months of life, and they can be observed in approximately 2% of neonates.27 Compared to acquired nevi, the melanocytes in congenital nevi tend to extend deeper into the dermis and even the subcutaneous tissues, tracking along appendages such as hair follicles.

CMN enlarge in proportion to the child’s growth, with estimated factors for increase in size from infancy to adulthood as follows: head, 1.7-fold; trunk and upper extremities, 2.8-fold; lower extremities, 3.4-fold.28 The lesions are categorized on the basis of final size into 3 major groups: small (< 1.5 cm); medium (1.5–20 cm) (Fig. 361-3A); and large (> 20 cm; in a neonate, > 9 cm on the head and > 6 cm on the body) (Fig. 361-3B). Most CMN are small; large CMN are estimated to occur in only approximately 1 of 20,000 births. Large CMN may have a “garment” distribution (eg, bathing trunk, cape) and are frequently accompanied by multiple smaller, widely disseminated “satellite” nevi.

The color of CMN ranges from tan to black, and the borders are often geographic and irregular (see Fig. 361-3A). Many CMN have an increased density of dark, coarse hairs (Fig. 361-3C). CMN may undergo age-related changes in appearance, frequently beginning as flat, evenly pigmented patches, then later becoming elevated and developing mottled pigmentation and a pebbly, verrucous, or cerebriform surface. Superimposed papules and nodules can arise and, depending on their clinical characteristics, may require histologic examination to exclude the possibility of a cutaneous melanoma.

Speckled Lentiginous Nevi (Nevus Spilus)

Several lines of evidence suggest that speckled lentiginous nevi (SLN), which have a prevalence of approximately 2% to 3%,30,31 represent a subtype of CMN.32 The “background” tan patch (café au lait macule–like) of an SLN (which in larger lesions may have a linear or blocklike configuration with sharp midline demarcation) is usually noted at birth or soon thereafter, with spots appearing over time. The superimposed pigmented macules and papules that develop on the background tan patch over time can range from lentigines to junctional, compound, and intradermal nevi to blue, Spitz, and classic congenital nevi (Fig. 361-3D). The risk of developing melanoma in SLN is thought to be similar to that of classic CMN of the same size range. SLN should therefore be followed clinically with periodic examinations and biopsy of suspicious areas.

MANAGEMENT AND COMPLICATIONS

MANAGEMENT AND COMPLICATIONS

Management of the “Moley” Child

The appearance of new nevi and the growth of such lesions are expected findings in children and adolescents. Individuals tend to develop nevi with a particular clinical appearance (eg, uniformly pink in color or tan with a brown rim).34 This results in a predominant type of nevus, or “signature nevus.”36 A nevus that has different characteristics from other nevi in a given patient (the “ugly duckling”) should be regarded with particular suspicion.36 A biopsy should be considered for nevi with characteristics such as unexpected rapid growth, ulceration, or development of asymmetry in shape or color. When a biopsy is performed, partial sampling should be avoided (with the exception of a large lesion in a cosmetically sensitive area).

A large number of acquired nevi and the presence of clinically atypical nevi each represents a marker of increased risk for development of melanoma, and patients with either trait should be followed with periodic total body skin examinations beginning around puberty.13,37 However, acquired nevi (banal or atypical) themselves have minimal malignant potential, with the lifetime risk of a particular nevus transforming into melanoma estimated to be about 1 in 10,000,38 and most cutaneous melanomas arise de novo (not in association with a nevus). As a result, there is no benefit to prophylactic removal of nevi.

Potential Complications and Management of Large CMN

Large CMN can be associated with systemic disease (eg, affecting the central nervous system [CNS]), whereas the consequences of small and medium-sized CMN are usually limited to the skin. There is ongoing debate regarding the magnitude of melanoma risk associated with CMN of various sizes and the best approach to their management.40-42 For patients with large CMN, the risk of developing melanoma (cutaneous or extracutaneous) is estimated to be 5% over a lifetime, with approximately half of this risk during the first 5 years of life (eTable 361.2  ).27,28 Cutaneous melanomas can arise subepidermally, making early recognition difficult. In some patients, the site of the primary melanoma is the central nervous system or retroperitoneum, while others have no identifiable primary site. Patients with a “giant” (> 40 cm) CMN in a posterior axial location that is associated with numerous satellite nevi have the greatest risk of developing melanoma.40,43 Melanomas less often arise within nevi restricted to the head or an extremity; to date, no well-documented primary cutaneous melanomas have been reported to develop within the satellite nevi themselves.43,44 Of note, deep soft tissue malignancies other than melanoma (eg, rhabdomyosarcoma, peripheral nerve sheath tumors) can also develop in association with large CMN.

).27,28 Cutaneous melanomas can arise subepidermally, making early recognition difficult. In some patients, the site of the primary melanoma is the central nervous system or retroperitoneum, while others have no identifiable primary site. Patients with a “giant” (> 40 cm) CMN in a posterior axial location that is associated with numerous satellite nevi have the greatest risk of developing melanoma.40,43 Melanomas less often arise within nevi restricted to the head or an extremity; to date, no well-documented primary cutaneous melanomas have been reported to develop within the satellite nevi themselves.43,44 Of note, deep soft tissue malignancies other than melanoma (eg, rhabdomyosarcoma, peripheral nerve sheath tumors) can also develop in association with large CMN.

Neurocutaneous melanocytosis (NCM) is due to a proliferation of melanocytes within the central nervous system in addition to the skin. NCM can occur in conjunction with (1) a large CMN, usually with a posterior axial location and (most importantly) accompanied by numerous satellite nevi (> 20 satellites); or (2) multiple (> 2) medium-sized CMN (accounting for about one third of NCM patients).45 Of note, NCM can also develop in patients with nevus of Ota (oculodermal melanocytosis).

CNS melanosis is best detected by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with and without gadolinium, and it is divided into symptomatic and asymptomatic forms. Symptomatic NCM occurs in approximately 4% of patients with a high-risk CMN, with onset of clinical manifestations (eg, hydrocephalus and seizures) at a median age of 2 years and a poor prognosis even in the absence of malignancy.43,46,47Asymptomatic NCM, with a diagnosis based on MRI evidence of CNS melanosis, can be found in as many as 25% of infants with a high-risk CMN.48 In a 5-year follow-up study, only 1 of 10 patients with MRI evidence of CNS melanosis went on to develop neurologic symptoms.48

For large CMN, early and complete surgical removal is often recommended as prophylaxis against the development of melanoma; removal typically requires staged excision with use of tissue expanders and skin grafting.49,50 However, it is usually difficult to remove every nevus cell in the lesion because of location, extensive size, and involvement of deeper structures (eg, fat, fascia muscle). Even theoretically complete excision of a large CMN does not eliminate the risk of melanoma, as primaries in the central nervous system and other sites can also occur (see eTable 361.2  ).

).

In addition to the risk of melanoma, the stigma of having these highly visible lesions has significant psychosocial consequences.41,50 In patients in whom surgical excision is not feasible, cosmetic benefit may be obtained from procedures such as curettage, dermabrasion, and ablative laser therapy (eg, carbon dioxide or erbium:YAG, sometimes combined with pigment-directed lasers), especially when done during the newborn period when there is a lower risk of scarring and active melanocytes are concentrated in the upper dermis.51,52

Whether or not resection of the CMN or other treatment methods are attempted, patients should be followed closely and any nodules or areas with suspicious changes examined histo-logically. Patients with a large CMN with satellite nevi or multiple medium-sized CMN should be screened with an MRI of the brain and (especially if the nevus overlies the posterior axis) spine during the first 6 months of life, then followed with serial neurologic examinations and repeat MRIs as indicated. Aggressive surgical procedures for removal of the CMN should be postponed in patients with symptomatic NCM.

Potential Complications and Management of Small and Medium-sized CMN

The risk for the development of cutaneous melanoma within small and medium-sized CMN is controversial and is thought to be 1% or less over a lifetime.49 Melanomas most often occur after puberty and tend to arise at the dermal-epidermal junction, in contrast to the earlier onset and deeper origin of many melanomas arising within large CMN.49,50

Small and medium-sized CMN are managed on an individual basis depending on cosmetic concerns, factors that hinder monitoring (eg, very dark color, irregular topography, “hidden” location), and history of concerning changes. Removal for medical reasons is usually not necessary.

PEDIATRIC MELANOMA

The overall incidence of cutaneous melanoma in the United States has increased dramatically in the past several decades, although it has leveled off in recent years. In adolescents, the rate of increase has been similar to that in adults (∼ 3% annually), whereas in children (age < 10 years), it has been lower (< 1.5% annually).55 The lifetime risk of cutaneous melanoma in children born today is estimated to be 1 in 58, compared to 1 in 250 in 1980.56 However, cutaneous melanoma is rare in the pediatric population, accounting for approximately 2% of childhood malignancies. In the United States, 1% to 4% of all melanomas arise in individuals under 20 years of age, and only 0.3% to 0.4% (300–400 cases per year) occur before puberty.57

Melanomas in prepubertal children often fail to exhibit the ABC features (asymmetry, border irregularities, color variability) that characterize most melanomas in adults. Instead, childhood melanomas are often amelanotic and may clinically simulate a wart, vascular tumor, or keloid; histologically, they often have features reminiscent of Spitz nevi (spitzoid melanomas).58 Although a greater proportion are of the aggressive nodular subtype, with thicker lesions at diagnosis and a higher incidence of lymph node metastasis than melanomas in adults, there is actually a lower incidence of recurrences in children and overall survival parallels adult disease.59,60

As discussed previously, the presence of numerous (eg, > 50) melanocytic nevi and/or atypical nevi are phenotypic markers of patients at increased risk for melanoma, particularly the superficial spreading type that occurs in adults and at times in adolescents. A family or personal history of melanoma, fair skin, red hair, and freckles represent additional risk factors that signal the need for especially diligent photoprotection and (particularly after puberty) periodic total body skin examinations. Rare conditions such as xeroderma pigmentosum (a group of inherited disorders of DNA repair) and large CMN can increase the risk of childhood melanoma.

DERMAL MELANOCYTOSIS

Whereas in normal skin only melanocytes in the epidermis and hair follicles produce melanin, dermal melanocytosis is characterized by the presence of dermal melanocytes that actively synthesize melanin. The blue color of such skin (ceruloderma) is due to the preferential scattering of shorter wavelengths of light by the dermal melanin, a phenomenon known as the Tyndall effect. The spectrum of dermal melanocytosis in children includes Mongolian spots and nevi of Ota and nevi of Ito (nevus fuscoceruleus).

MONGOLIAN SPOTS

MONGOLIAN SPOTS

Mongolian spots are ill-defined, homogeneous, gray-blue patches that are apparent at birth, typically on the sacral area and buttocks (Fig. 361-3E), in 85% to 100% of Asian neonates, more than 60% of black neonates, and less than 10% of white neonates.62 They are less often observed in extrasacral sites such as the upper back, shoulders, arms, and legs. The bluish discoloration results from the presence of active melanocytes in the middle to lower dermis. These melanocytes and the discoloration usually disappear by age 6 to 10 years; however, approximately 5% are still present in adulthood, especially those located on the distal extremities. Extensive dermal melanocytosis that affects the ventral as well as dorsal trunk, persists, and progresses in extent over time can represent a sign of a lysosomal storage disease (eg, Hurler syndrome or GM1 gangliosidosis).63

NEVI OF OTA AND ITO

NEVI OF OTA AND ITO

Nevus of Ota (nevus fuscoceruleus ophthalmomaxillaris, oculodermal melanocytosis) presents as speckled grayish-brown to blue-black patches involving the skin, conjunctiva, sclera, tympanic membrane, and/or oral and nasal mucosa in areas innervated by the first and second divisions of the trigeminal nerve.64 Involvement is unilateral in approximately 90% of cases. In contrast to Mongolian spots, the discoloration is often mottled rather than uniform, and the density of melanocytes is greatest within the upper dermis. Nevus of Ota occurs most commonly in blacks and Asians (1–2/1000 in Japan), and there is an approximately 4:1 female-to-male ratio. The discoloration is evident at birth or within the first year of life in more than half of affected individuals, and in the remainder, it becomes apparent around puberty; in both instances, the lesions then persist throughout the patient’s life.

Approximately 10% of patients with a nevus of Ota develop glaucoma, and ipsilateral sensorineural hearing loss has also been described. Melanoma of the uveal tract occasionally arises in association with nevus of Ota, most often in white adults.65 Patients with nevus of Ota should be followed with yearly ophthalmologic examinations. The skin discoloration can be treated with pigment-specific lasers (eg, the Q-switched ruby, alexandrite, or Nd-YAG); this typically requires several sessions, but the outcomes are often excellent.66

Nevus of Ito is a type of congenital dermal melanocytosis involving areas of skin innervated by the posterior supraclavicular and lateral brachiocutaneous nerves. It is otherwise clinically and histopathologically similar to nevus of Ota.

OTHER PIGMENTED LESIONS

FRECKLES AND LENTIGINES

FRECKLES AND LENTIGINES

Freckles and lentigines are pigmented macules that result from increased activity of epidermal melanocytes.67 In contrast to freckles (ephelides), which are commonly observed in young children with fair skin and fade in the absence of sun exposure (eg, during the winter), lentigines are persistent. There are 2 major types of lentigines: solar lentigines and simple lentigines.

Like freckles, the distribution of solar lentigines is limited to sun-exposed areas, particularly sites of greatest cumulative exposure such as the face, dorsal aspect of the hands, extensor forearms, and upper trunk.67 Although the prevalence of solar lentigines increases with age, they can develop in fair-skinned children who have had significant sun exposure, especially on the shoulders following severe sunburns. Multiple tan to dark brown macules, often with irregular borders, are typically present; they range from a few millimeters to more than 1 cm in diameter. Diligent sun protection is advisable for all children with freckles or solar lentigines.

Simple lentigines typically appear during childhood as sharply circumscribed, round to oval, uniformly brown or brownish-black macules that are less than 5 mm in diameter. They are usually few in number and (unlike solar lentigines) have no predilection for sun-exposed sites. However, multiple lentigines are observed in several genetic disorders including LEOPARD syndrome, Carney complex, Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, Cowden disease, Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome, xeroderma pigmentosa, and neurofibromatosis type 1 (eTable 361.3  ).

).

CAFÉ AU LAIT MACULES

CAFÉ AU LAIT MACULES

Café au lait macules (CALMs) are flat, pigmented lesions that may either be present at birth (see Fig. 361-3E) or appear during early childhood, often first becoming noticeable following sun exposure in lightly pigmented individuals. They represent localized oval areas of increased melanogenesis. Although a single CALM can be found in 25% to 35% of children, less than 1% of children have more than 3 CALMs.68 CALMs range from a few millimeters to more than 15 cm in size and enlarge in proportion to the child’s growth. Their color varies from tan to dark brown and is usually a few shades darker than that of the uninvolved skin.

In patients with McCune-Albright syndrome or pigmentary mosaicism of other etiologies, CALMs may have a segmental distribution with sharp midline demarcation and an irregular, jagged outline (“coast of Maine”). McCune-Albright syndrome, which is due to mosaicism for activating mutations in the gene encoding the G protein Gsα subunit, also features polyostotic fibrous dysplasia, precocious puberty, and other endocrinopathies. The presence of 6 or more CALMs (measuring ≥ 0.5 cm in prepubertal children and ≥ 1.5 cm in adults) represents a criterion for the diagnosis of neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) that is met by most affected individuals by adolescence (Chapter 360).

BECKER NEVI (BECKER MELANOSIS)

BECKER NEVI (BECKER MELANOSIS)

Becker nevi (Becker melanosis) represent fairly common cutaneous hamartomas characterized by variable epidermal thickening, enhanced melanocyte activity, increased size and number of hair follicles, and excess dermal smooth muscle. They exist on a spectrum with smooth muscle hamartomas (not melanocytic nevi). Becker nevi can be evident at birth, but most are first noticed around puberty. This timing, the male-to-female ratio of 5:1, increased terminal hairs within approximately half of lesions, and reports of acne vulgaris localized to lesions reflect hypersensitivity to androgens within Becker nevi.71 A Becker nevus classically manifests unilaterally on the shoulder and upper trunk as a large tan to brown patch that breaks up into smaller “islands” at its periphery. Lesions can also occur on the lower trunk and thigh. Associated developmental abnormalities, such as hypoplasia of the ipsilateral pectoralis major muscle or breast, are occasionally observed.

DISORDERS OF PIGMENTATION

POSTINFLAMMATORY PIGMENTARY CHANGES

POSTINFLAMMATORY PIGMENTARY CHANGES

Inflammatory dermatoses often lead to pigmentary changes, which are most pronounced and persistent in patients with darker skin. Although either hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation can occur, particular skin diseases tend to resolve with pigmentary sequelae of a certain type. Most postinflammatory pigmentary alterations resolve spontaneously, albeit slowly, over months to years.

Postinflammatory Hypopigmentation

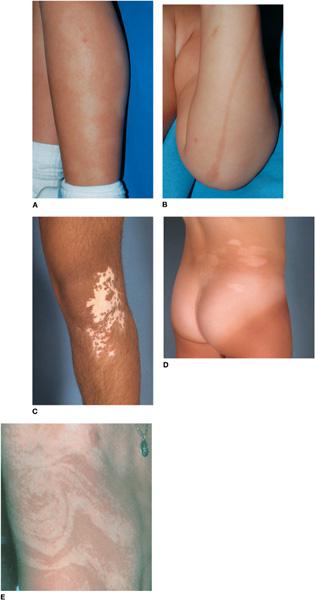

Postinflammatory hypopigmentation is commonly observed during and after flares of seborrheic dermatitis, atopic dermatitis (Fig. 361-4A), psoriasis, and pityriasis lichenoides chronica (Chapter 358).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree